x

ABSTRACT

As a three-year-old, my son was a philosopher king. One day, in all sincerity, he asked, Why can’t the good people just kill all the bad?

I have a personal relationship with Jesus, who was able to procure a list that his father’s meticulous angels had drawn up. My credit cards are linked to air miles, which I have never spent. With the list, free global travel, and my (legal) assault rifle, I was able to dispatch the undesirable. The babies initially posed a quandary: on the list, destined for a life of casual cruelty and selfishness, but what would happen once I offed their inevitably corrupting parents? What if the babies were raised by kind people? It’s always nature versus nurture.

If I thought any of this would work, yes. There is nothing I wouldn’t try to make this world safe for my son. What to do?

You can’t promise the child a just, or kind, or beautiful world. But you can teach him where to find it, in snatched glances and in-between spaces. You can teach him how to look.

.

LITERATURE REVIEW

The pig running with a knife stuck in its back is already roasted. The bent-over nun is bare-bottomed. Baked fish fly from stream to plate, the shacks are made of sugar, the pastry roads flake under your feet. You are never cold and can sleep all day. A paradise, a parody, a broke-back peasant’s dream. You come to Cockaigne by way of Breughel, or medieval poems. Cockaigne, variant Cockney. Coken, of cocks, and ey, egg. Meaning, the cock’s egg, an impossible thing.

The men of Plato’s Republic shared wives, children, and resources. The original Utopians – Thomas More’s – shat in gold chamber pots. Their slaves were shackled with gold, and their prisoners were crowned with riches. Wealth was dirty, something to be eschewed. These were theoretical – or satirical – attempts to deal with enduring human problems: sex, money, work, power. The jealous guarding, coveting and/or avoidance thereof.

Superimpose the dream of a just society onto the vision of a lost city of gold and you will, like Candide, see Voltaire’s El Dorado. Built of gold and silver, the city is stately and well-proportioned. Children play with unhewn chunks of ruby, emerald, and sapphire; a sense of ease derives from this great wealth. Peace and great contentment, beauty and science. There are no prisoners or priests.

Utopia literally means no place. An impossible thing.

/

Seaside

The town of Seaside is privately owned, which means that the developers were able to make it almost exactly how they wanted. Architects of the ideal. The village is designed to be walkable, with useful and attractive public spaces. Located on the coast as the name suggests, or rather, prudently set back several hundred feet, it is the town where The Truman Show was shot. The pastel houses come in various flavors: Victorian, Neoclassical, Modern, Postmodern, and Deconstructivist, all with friendly front porches. The town has a motto: A simple, beautiful life.

My mother and father took me and my sisters and their families to Seaside one year for a holiday get-together. Although I was still single, my sisters had small children, and the Florida coast seemed like safe bet for an easy and pleasant beach vacation. It was all that: easy, safe, pleasant.

The Seaside Institute, founded and run by the town’s developers, has an “academic center” in the middle of town. The Institute’s mission is to “help people create great communities.” Apparently, it was founded on the premise that great communities can be created, ex nihilo, by a group of hard-working, well-intentioned, great people.

I remember walking the streets in search of a meal. The streets, the sidewalks, the manicured yards, and the friendly front porches were always empty.

Architectural styles in Seaside, Florida (via Wikimedia Commons)

Architectural styles in Seaside, Florida (via Wikimedia Commons)

.

Ecotopia

In Ecotopia, trees are worshipped, love is free, technology is embraced, and a woman is president. The borders are secured; a hefty arsenal keeps the little country safe. The late Ernest Callenbach, earnest prophet, early recycler, organic gardner, film buff, and author of the eponymous novel from the 1970s, imagined what might happen if the feminists, Black nationalists, and environmentalists of that time created a great community and seceded from the union. The book’s form is that of a visiting journalist’s diary; it is widely taught in colleges now.

In Ecotopia, Black people have retreated to Soul City – formerly Oakland, CA – their own country within a county.

The culture of Soul City is of course different from that of Ecotopia generally. It is a heavy exporter of music and musicians…

The people living in Soul City are flashier, drinking high quality Scotch whisky, trading in luxury good, driving private cars.

And, the (white) Ecotopians love Indians:

Many Ecotopians are sentimental about Indians, and there’s some sense in which they envy the Indians their lost natural place in the American wilderness. Indeed this probably a major Ecotopian myth; keep hearing references to what Indians would or wouldn’t do in a given situation. Some Ecotopian articles – clothing and baskets and personal ornamentation – perhaps directly Indian in inspriation.

This, despite the presence of any real Native Americans.

Non-lethal war games help men discharge their natural aggression. Kind of:

Goddam woman is impossible! Got really turned on at the war games…and made no resistance when one of the winning warriors came up, propositioned her, and literally carried her away (she weighs about 130)…Later…she was relaxed and floppy, and I tossed her around on the bed a little roughly, wouldn’t let her up, more or less raped her. She seemed almost to have expected this.

Can’t blame Callenbach for trying, but a single author will always be limited in his vision for other people. Stereotypes, segregation, erasure, rape. All with the best of intentions. And with some good ideas mixed in.

Efteling Theme Park Talking Tree

Efteling Theme Park Talking Tree

.

Cascadia

If Ecotopia took a deep breath, expanded its borders to include parts of British Columbia, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, it would be Cascadia, the bioregion where I live and for which there are occasional secessionist agitations. There is a flag for Cascadia and I’ve seen bumper stickers around town, though have yet to see a referendum on the ballot. Not surprisingly, the cultures and the boundaries of the two hypothetical countries more or less align with one another and with the real Pacific Northwest.

In the late 1800s and early 1900s, before Ecotopia or Cascadia were dreamed up and named, this area was home to a number of communes and experiments in ideal (white) society. The West was a place for imagination and ambition; smallpox and colonialism had made vast swaths of it almost unpeopled. Men with grand socialist ambitions believed that the Pacific Northwest – Washington State in particular – could be a petri dish in which socialist colonies would take hold, and then infect the whole country.

Harmony, Freeland, and Home were all well-established colonies in northwest Washington. Equality thrived until an arsonist burnt it down.

.

Omelas

I was a child who regarded the adult world as inherently corrupt or, at best, misguided. I felt affirmed in this when I read about Ursula Le Guin’s Omelas, the perfect world made possible by the existence of a single spot of suffering. A child locked in a cramped, filthy basement, a child who is kicked and beaten, fed just enough to keep alive, a child who is alone and unloved. A child who is taken from the good life once s/he is old enough to remember the good life; this point of reference allows the child to understand the depth and injustice of his or her suffering.

The prosperity, health, kindness, and gentle wisdom of Omelas, are all because of the child’s misery. Most citizens of this Utopia accept that this is simply the way their perfect world works, but some are appalled, and blow that popsicle stand. Walk away, and never come back.

A side-note: Omelas, or at least its namesake, would be located in Ecotopia. Omelas is Salem, the capital of Oregon, spelled backwards. With an O slapped on for euphony.

.

America

We the People of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defense, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America. – Preamble to the United States Constitution

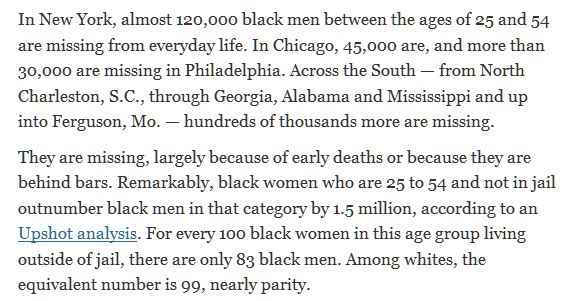

And. What we lock in the basement.

/

Z.1

We don’t have to wait for some grand utopian future. The future is an infinite succession of presents, and to live now as we think human beings should live, in defiance of all that is bad around us, is itself a marvelous victory. – Howard Zinn

.

Z.2

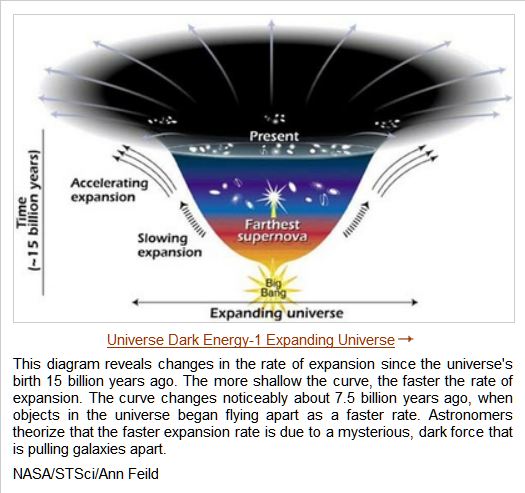

The Mato Grosso region of Brazil is covered in trees. It’s a jungle. According to legend and rumor, there was a grand city tucked away in the Amazonian rainforest. Many men of European descent searched there for what they believed might be the true El Dorado. Percy Fawcett, a British explorer of the early 20th century, was obsessed with the place. He took clues from Indigenous stories and Manuscript 512, a document he came across in Rio de Janeiro library archives in 1920. The account, presumably by the Portuguese bandareinte (settler and fortune hunter) João da Silva Guimarães, is titled Historical Relation of a hidden and great city of ancient date, without inhabitants, that was discovered in the year 1753. It tells of gold in the streams and buried treasure, as well as of a grand, abandoned city.

Fawcett wanted not gold, but to name, claim, and chart the world. A knowledge conquest. He called this city Z, and referred to it only cryptically in his notes and letters. Fawcett made it his life’s work to find Z. In 1925, on his eighth expedition, Fawcett, his son, and his son’s best friend vanished into the jungle. They were last seen crossing the Upper Xingu River.

There were rumours that Fawcett had been eaten by cannibals, rumours that he’d gone native and become a tribal king. Z was dismissed as yet another El Dorado delusion, the entire Amazon was seen as a counterfeit paradise, incapable of sustaining urban life, and Fawcett was dismissed as a crank and a dilettante.

Crazy, but Fawcett was right. Z was there all along. Within reach, or almost.

Kuhikugu is a vast archeological complex at the headwaters of the Xingu River in Brazil. Where Fawcett thought the City of Z would be. The Kuikuro are likely descendants of the estimated 50,000 people who lived in Kuhikugu about 1,000 years ago. When archeologists started listening to the Kuikuro and then looking at satellite imagery enhanced by LiDAR, they started seeing Kuhikugo. The towns of Kuhikugu are mathematically laid out on cardinal points, connected by roads, bridges, and canals, protected by palisades and concentric moats. The presence of terra preta, a type of soil that is formed by long-term cultivation, and of earthen berms likely indicate agriculture and fish-farming.

Kuhikugu archeological complex

Kuhikugu archeological complex

Increasingly, there is thought that the Americas were populous, urbanized, and widely farmed prior to European contact. The myth of El Dorado didn’t spring from nothing: conquistadors, bandeirantes, European explorers, Jesuits did see gold, riches, and great cities. But like the physics principle that tells us observation changes what we see, the European reporters infected the subjects of their reportage with disease. The natives died. In the Amazon, the jungle swallowed the cities whole.

What failed in the quest for Z, for El Dorado, was imagination, or sight.

.

Z.3

Every alphabet comes to an end. From sea to shining Z. There is speculation that American democracy – our attempt at a just society – is at an end. Our new President won by promising safety and freedom for some people at the expense of safety and freedom for other people. By promising the return of a lost Utopia. Make America Great Again.

If Americans had been able to see this country has never been just and great for all who live here, and, too, if Americans had been able to see the very real – if imperfect – greatness of a country founded on ideals of equality and justice, maybe they wouldn’t have felt a need to make it great again. Maybe they would’ve voted more modestly, for making America incrementally better.

Map of a Utopia

Map of a Utopia

.

METHODOLOGY

I look for meaning in a small room. My analyst is a tiny, birdlike woman. She speaks softly, and can say shocking things. She sits in her chair. I sit on the couch. It is too soft. I would never dream of lying down. There’s a view of a parking lot and also a microbrewery.

The purpose of my visits with her are wholeness, integrity. She is a Jungian, so she comes at all this from the perspective that you have to dredge the unconscious, sift through your dark, ugly, unseen, painful matter. You must unfold, unpack, remember, shake out everything that’s been pressed: depressed, repressed, oppressed. Everything you’ve locked up, you must release. Everything in the basement gets hauled upstairs, into the sunlight.

.

PRESENT STUDY

A few years ago, my husband, our young son, my mother and I went to a villa in Baja that both friends and the internet promised was heaven on earth. It had been a hard winter.

What we now call Baja California was thought by Spanish conquistadors to be an island, quite possibly the island paradise described in a novel popular at the time.

At the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California, very close to that part of the Terrestrial Paradise, which was inhabited by black women without a single man among them, and they lived in the manner of Amazons. They were robust of body with strong passionate hearts and great virtue. – Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo, The Adventures of Esplandián

Island of California

Island of California

We took a rough dirt road – an arroyo, really – from the airport on the Pacific coast to our destination on the Gulf. It was night. My mother was buckled in, she’s religious about seat belts and safety, if not about God or anything else. She was also clinging to the handle above the car’s door and offering helpful driving tips, like slow down. My husband was driving, maybe a little fast. My son was bouncing in the back seat next to me, thrilled for any kind of adventure. There were no villages, no houses, no streetlights along the way. Our world was limited to the wan beams of our headlights. When we finally came to the other side, we unknowingly shot by the villa, and had to backtrack to find it.

Morning, and we woke to beauty.

We wandered up to a palapa for breakfast – buckwheat pancakes and great slabs of papaya – and then one of the owners gave us a tour. He was a soft-spoken gringo of late middle age, polite, not effusive. The villa was comprised of a main house, where the owners lived, and a number of casitas. The workmanship of the place was meticulous; the balconies and curved balustrades, the tilework, the fountains. The owners themselves had built the place. Please stay away from the main house, on the paths that wind through the yucca, the palms, the plumeria, and hibiscus. I saw a wild fox perched atop a saguaro.

As my mother, my husband, our guide, and I stood on a terrace gazing out to the sea – I remember I was running my hand up along a smooth, coral-colored Tuscan column – we heard a splash behind us.

My then five-year-old son was at the bottom of the pool. He didn’t know how to swim. Fully clothed, I jumped in to save him. I was wearing a long skirt which covered my face as I entered the water. I reached out blindly. My boy wasn’t there.

When I tugged the skirt off from face and could see, our guide was hoisting him out of the pool. He’d calmly knelt down at the edge, reached into the pool and grabbed my son as he’d surfaced for air. He didn’t even get his sleeves wet.

The pool had mermaids mosaicked on the bottom.

Before we wandered down the hill to the beach, I buckled my son into the life vest I’d packed. Beaches back home in the Salish Sea are gray-green and rocky, covered in kelp, barnacles, and eel grass. This one was absolutely blank, just hot sand and blue water.

We encountered another young boy at the shore. Named after an archangel, he was a grandchild of the villa’s owners. Oh, so-and-so? I asked, naming our guide. No, all of them, he said. I learned that a wealthy, graying, seemingly happy commune owned the villa. My boy and the other played in the ocean waves for hours, laughing. The sand glimmered as if with gold as it was kicked up by the clear water.

In Baja

In Baja

We accept the reality of the world with which we’re presented. – The television director who controls Truman’s world in The Truman Show

The Lyman Family, also known as the Fort Hill Community, was the creation of Mel Lyman, a banjo and blues harmonica player. Photos, including one shot by Diane Arbus, show a man of thin body, hollowed cheekbones, a hot gaze.

In the 1960s, the group attracted some wealth and intelligence, and members included architects, artists, and the daughter of a famous painter. Although they dabbled in LSD and astrology, they hated hippies. Men wore their hair short, and women did as they were told. Wives were not shared concurrently, but serially. Mel fathered at least 5 children by 4 women. As with children in Plato’s Republic, the Lyman kids were removed from their parents and raised collectively. The Family also dabbled in guns, racism, and bank robbery. One member was shot to death at the scene of their single attempted heist and another, actor Mark Frechette, was arrested. Frechette later died in a weightlifting accident in prison.

The Lyman Family recovered from the bad publicity, and continued to buy and develop properties for their communal living. A farm in Kansas. A base in Los Angeles. A loft in Manhattan. A compound on Martha’s Vineyard. A villa in Baja. They started selling their skills, and incorporated a high-end construction company, which designs and builds homes for Hollywood directors and movie stars.

According to the Family, Mel Lyman died years ago, on his fortieth birthday. The cause and location of death were never disclosed, and his body was never produced, leading to speculation that he went into deep hiding, and may still be among us.

Some of the Family spend most of the year down in Baja; the grandkids don’t visit as much as the elders would like, so they’ve started renting out casitas to tourists.

The villa was self-sufficient: solar-powered, eco-friendly, off-the-grid, farm-to-table. At one dinner, after an owner slid a huge plate of food in front of me, I asked if the chicken was one that he’d raised. Costco, he said. Similarly, when I complimented the person I thought was the cook, I was told that actually, the Mexican did all the cooking.

I never saw this Mexican, nor any of the other workers, though ostensibly it was they who kept the pool so clean, the garden so lush with water trucked in weekly from afar. I heard, occasionally, the voices of children. Once I peeked into the off-limits zone and saw a tiny shack. That must’ve been where the Mexicans lived.

I was a big empty HOLE trying to fill itself with TEARS – Mel Lyman, Autobiography of a World Savior

Seen from the beach, the villa’s grounds were an island of green in the sere brown land. Baja is a bone dry finger that pokes into saltwater. It presents two obvious possible deaths: one by drowning, the other by thirst. A third struck me as we were climbing up the stairs from the beach to the summerhouse: death by sunburn. Although I’d assiduously reapplied sunscreen to my child’s skin throughout the day, I hadn’t done so on my own. I was scorched, and hurt for days.

My thighs are now freckled, sun-spotted from the burn. Skin damage because of Baja. When I think of that time, I try to remember that the beauty and kindness shown, I try to remember that people sometimes grow and change, that every family is an expression of an attempt, that I am judging based on very little. The archangel and his mother, both progeny of the Family, were lovely. But really what I think about is Mel, and the shuttered away Mexicans, and the fact that there are no trees.

.

FINDINGS

- Utopias are dystopias or satires; the kings are harmonica players.

- Actual attempts at ideal society fizzle out, as do actual attempts at living. Which is not necessarily a value judgment.

- Now you can strap the world you want onto your head. It’s in a box, this virtual world, this reality. You are immersed, as if in liquid. You move through this liquid world, seeing everything as if you’re right there. One can easily imagine an ideal world (safe, beautiful, egalitarian, fun) being successfully marketed and inhabited. Maybe you’ll be able to spend most of your life there. But from the outside, you’re still just a person with your eyes covered.

- Once, while walking along a river in the Canadian Rockies, hand in hand with a poet with whom I was wildly infatuated, I saw a vast herd of elk. I pointed them out to my companion, who was confused. I looked again. What I’d taken for elk were simply the dark spaces between trees in the forest. It is possible to confuse absence and presence.

- The Kingdom of God, I’ve heard, is all around us, if we have but vision to see.

- When not advocating wholesale genocide, my then three-year-old son sometimes (at least once) had moments of coruscating wisdom. One night on the tiny ferry we take from the mainland to our island home, he climbed out of his car seat and started speaking, as if in tongues:

I am everything

I am a grizzly bear shark deer

I’m all the animals in the world

I am everythingI’m looking at the moon and the stars

I’m the ocean and the fish

I am everythingI’m the boats I’m the trains I’m the excavators

I’m all the pieces of equipment

I’m the roads I’m the cars

I am the signsI’m the houses

I’m everything in the houses

I’m the cupboards I’m the oven I’m the cereal I’m the food

I’m the computers I’m the lights

I am electricityI’m the windows I’m the grass

I’m the trees I’m the birds I’m the sky

I am everythingThen he went back to potty talk and whining. We are all of us occasional prophets trapped in bewildered flesh.

- Utopia is a fertile lick of land in the floodplain of the Skagit River in Washington State. There were Utopians there once, briefly. They fled to higher ground during the first wet season, but the name stuck. My husband recently bought a plot of land there, in Utopia. On it, he will grow trees. They, the big leaf maples, acer macrophyllum, will be the new Utopians.

.

CONCLUSION

When my son was an infant and started to cry, I’d take him out under the Japanese maple. The green light under the leaves would calm him. Or maybe it was the aerosols. Trees talk with one another by releasing tiny chemical particles into the air. These arboreal perfumes are believed to make people feel healthier and happier. The Japanese invented a phrase for walking through the woods to enhance good health: shinrin-yoku, or forest bathing. These same aerosols seed clouds to make rain and cool our planet down.

Aerosols are tree cafe chatter, you’re not quite sure which tree is saying what. An even more sophisticated communications system, tree-to-tree talk, lies underground. The mycorrhizal network, also known among scientists unafraid of bad puns as the Wood Wide Web, is the connecting of various tree roots to one another by fungal filaments. The trees give necessary carbon to the fungi, the fungi reciprocate with food and drink, and act as carriers for chemical missives, nutrient love letters. A tree under attack by aphids or fire in one part of the forest can sound the alarm to other trees far away. Do they have feelings, these trees? Is it why a mother tree will fend off the growth of other trees nearby, but make space for her children? Why she will give them everything she has?

Mycorrhizal Network

Mycorrhizal Network

Charles Darwin, after Origin of the Species, turned his attention to plants. He believed that trees were like very slow-moving, upside-down animals, burying their root-brains deep in the dirt, and flashing their sex bits up above. Among the ancient Greek, the Druids, the Italian streghe, trees spoke with the gift of prophecy. Oracular trees.

Consider the trees.

Where I live now, on Coast Salish land, tree-people were the first people, then salmon-people, killer-whale-people, crow-people and others. After a while, human-people came along. I have no doubt that life was hard, and I don’t wish to romanticize – or to have lived in – any time other than my own. I do, though, wonder what justice looks like when trees are considered teachers and equals, as they were. I’d think that differences in our own species – language, culture, color, gender, ideas about god, fashion, all that – would look smaller, hardly worth mentioning, or at least more gracefully negotiated. If you can respect a cedar, might it be easier to respect someone who is not a mirror of yourself? Maybe we wouldn’t regard the world – or each other – simply as resources. In a world where everything is holy, the sun glints off the raindrops on the web of the divine, making the connection between all things visible.

Balance must look different, too, when man is not the fulcrum. No architect or author. No pale king.

It is easy to lapse into utopian thought. This world is bruised and marked and hardened. But still, it flickers between what it is and possibility. We must imagine what we cannot yet see, or can glimpse only through the cracks: a society made up of all these different kinds of tree, animal, and human people, learning the ways of one another and of the air, the water, the living dirt.

—Julie Trimingham

REFERENCES

The Republic, Plato, http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/1497

Utopia, Thomas More,http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/2130

Candide, Voltaire, http://candide.nypl.org/text/chapter-18

Utopias on Puget Sound, 1885–1915. LeWarne, Charles Pierce: Seattle: University of Washington Press

The Return of the Utopians, Akash Kapur, The New Yorker, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2016/10/03/the-return-of-the-utopians

Ecotopia, Ernest Callenbach, Bantam Books

Ernest Callenbach New York Times obituary: http://www.nytimes.com/2012/04/27/books/ernest-callenbach-author-of-ecotopia-dies-at-83.html

The Ones Who Walk Away form Omelas, Ursula Le Guin, http://engl210-deykute.wikispaces.umb.edu/file/view/omelas.pdf

Utopia, Thomas More, available online at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2130/2130-h/2130-h.htm

Autobiography of a World Savior, Mel Lyman, http://www.trussel.com/lyman/savior.htm

Steven Trussel has an online compendium of Mel Lyman information: http://www.trussel.com/f_mel.htm

The Lyman Family’s Holy Siege of America, David Felton, http://www.rollingstone.com/culture/features/the-lyman-familys-holy-siege-of-america-19711223

Once Notorious 60s Commune Evolves into Respectability, http://articles.latimes.com/1985-08-04/news/vw-4546_1_lyman-family/2

The Lost City of Z, David Grann, http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2005/09/19/the-lost-city-of-z

Under the Jungle, David Grann, http://www.newyorker.com/news/news-desk/under-the-jungle

More links and information on Percy Fawcett: https://colonelfawcett.wordpress.com

A translation of Manuscript 512: http://www.fawcettadventure.com/english_translation_manuscript_512.html

1491, Charles C. Mann, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2002/03/1491/302445/

The Island of California was a common misconception among the Spanish in the 16th century. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Island_of_California

The Island of California was thought to be a paradise, inhabited by Black women, ruled by Queen Calafia/Califia.

The Atlantic Monthly published an article on The Queen of California in 1864, Volume 13. https://books.google.com/books?id=pd9rm7JwShoC&dq=%22Queen%20of%20California%22&pg=PA265#v=onepage&q&f=false

The Power of Movement in Plants, Charles Darwin and Sir Francis Darwin, 1925, available for reading online at http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/5605

The Intelligent Plant, Michael Pollan. http://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2013/12/23/the-intelligent-plant

Do Plants Have Brains? http://www.naturalhistorymag.com/features/152208/do-plants-have-brains

Radiolab on tree talk: http://www.radiolab.org/story/from-tree-to-shining-tree/

Suzanne Simard’s TED talk on how trees talk to each other: https://www.ted.com/talks/suzanne_simard_how_trees_talk_to_each_other?language=en

Information on very old trees in Britain: http://www.ancient-tree-hunt.org.uk/discoveries/newdiscoveries/2010/The+Pulpit+Yew

Photographer Beth Moon has taken pictures of some ancient, powerful trees. You can see some of these photos from Portraits of Time and Island of the Dragon’s Blood. http://bethmoon.com/portfolio-page/

Beth Moon’s stunning images capture the power and mystery of the world’s remaining ancient trees. These hoary forest sentinels are among the oldest living things on the planet and it is desperately important that we do all in our power to ensure their survival. I want my grandchildren – and theirs – to know the wonder of such trees in life and not only from photograpshs of things long gone. Beth’s portraits will surely inspire many to help those working to save these magnificent trees. — Dr. Jane Goodall

I believe it is through the unique vegetation that the spirit of Socotra is defined, with mythical trees like the dragon’s blood tree or the fabled frankincense trees and the island’s culture so closely linked to nature which sets this island apart from the rest of the world.” — Beth Moon

The observer effect in physics simply states that the act of observing will change that which is being observed. It is similar to, though different from, Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle which states that increased precision in measuring the position of a particle will diminish precision in measuring the momentum of the particle, and vice versa. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Observer_effect_(physics)

Smithsonian archaeologist Betty Meggers (1921-2012) is credited with coining the phrase counterfeit paradise, referring to the Amazon. Her book Amazonia: Man and Culture in a Counterfeit Paradise was, and remains, controversial in its contention that pre-Columbian Indigenous populations were, due to environmental restrictions, small and not very complex.

x

Julie Trimingham is a writer and filmmaker. Her fictional travelogue chapbook, Way Elsewhere, was released in May 2016 by The Lettered Streets Press (https://squareup.com/store/lettered-streets-press/). She regularly tells stories at The Moth and writes essays for Numéro Cinq magazine. Gina B. Nahai blurbed Julie’s first book, saying, “A novel of quiet passion and rare beauty, Mockingbird is a testament to the power of pure, uncluttered language—a confluence of feelings and physicality that will draw you back, line after graceful, memorable, line.” Julie is currently drafting her second novel, and is a producer with Longhouse Media (http://longhousemedia.org) on a documentary film about the Salish Sea.

x

x

Whirlpool galaxy,

Whirlpool galaxy,

![goldwing[1]](https://numerocinqmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/goldwing1.jpg)

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.