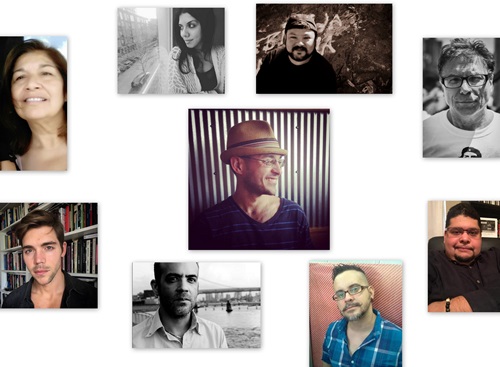

Jonathan Marcantoni (center); Clockwise from top left: I. C. Rivera, Ricardo Félix Rodríguez, Nelson Denis, Rich Villar, David Caleb Acevedo, Charlie Vázquez, Chris Campanioni, and Corina Martinez Chaudhry.

Jonathan Marcantoni (center); Clockwise from top left: I. C. Rivera, Ricardo Félix Rodríguez, Nelson Denis, Rich Villar, David Caleb Acevedo, Charlie Vázquez, Chris Campanioni, and Corina Martinez Chaudhry.

.

Recently, I assembled seven authors—Charlie Vázquez, author and COO of Editorial Trance; Chris Campanioni, author of Tourist Trap; Isandra Collazo Rivera, author of Across the Border: Interview with a Refugee; David Caleb, author of Cielos Negros; Ricardo Félix Rodriguez; Rich Villar, author of Comprehending Forever; Nelson Denis, author of War Against All Puerto Ricans—and Latino Lit advocate and founder of The Latino Author, Corina Martinez Chaudhry, to discuss the state of Latino lit in the United States, Mexico, and Puerto Rico. We covered issues as far ranging as the exclusion of Latino authors from the greater American literary canon, to identity politics and social limitations inside and outside of the US, to style and approaches to writing, to social media and, finally, the future of Latino literature. While these artists come from a wide variety of backgrounds and disciplines, the commonality of their struggles demonstrates the universality of art and the collective need for our communities to expand our definition of what we can accomplish through unity and ingenuity. The conversation has been edited for clarity and fluidity.

Jonathan Marcantoni: What are the biggest challenges you face not only as a Latino author, but in regards to the way you write? What kinds of support systems are there for Latino writers where you live?

Charlie Vazquez: The biggest challenge I faced as a Latino writer who began writing daily in the mid-1990s was writing about queer protagonists and writing about them honestly.

David Caleb: I must say that many people have tried to label me as a queer author, regardless of everything else I’ve written and done. It has taken me almost a decade to be recognized as a bona fide fantasy, scifi and horror writer, and not just a queer author.

Charlie Vazquez: I would say that nowadays there seems to be a lot of obstacles in breaking in to better book deals, such as less interested agents than for other folks and genres such as white folks and mystery writers. I think that this is improving, however.

Chris Campanioni: Charlie brings up a good point here: as cultural norms have shifted, it’s gotten easier for me to write about subsets of culture that were not really mainstream or literary, even as recent as 2012. I recall when I began sending out query letters to agents for Going Down, which is a novel about Latino identity but also fashion and commodities and pop culture from the perspective of a male model, probably seventy-five percent of the responses read “Chris” as “Christina” and championed the story about a strong Latina character in the world of modeling or, conversely, loved the idea of re-making The Devil Wears Prada for Latino audiences. No one heard or cared very much about male models, especially Latino ones, especially in the literary world. So the publishing world was reflecting the singular gaze of the fashion world I was responding to. Fast forward to 2015 and I think Latino representation in the fashion industry is much more widespread; literary fiction about the fashion industry seems much more well-received and easier to market today too.

David Caleb: In Puerto Rico, we have quite a predominant literary scene, perhaps stronger than the reading scene. Perhaps. The first decade of the 21st Century saw grand literary efforts in rescuing readers: we have a multidisciplinary BA in Creative Writing from the University of Puerto Rico in Río Piedras, and a Master’s in Literary Creation from the University of the Sacred Heart. Likewise, we have many literary guilds, such as Cofradía de Escritores, the Liga de Poetas del Sur, the group A Voces (a group of queer writers, direct heirs from the former HomoerÓtica collective) and so many others. We are producing a lot of literary work and of the highest quality. We also have many writers of renown who are taking the teaching mantle to show the literary ropes to the new generation of upcoming writers, such as Mayra Santos-Febres, Yolanda Arroyo-Pizarro and Max Chárriez. We even have graduates from the Literary Creation Master’s teaching creative writing in Ireland, such as our own Iva Yates. Finally, we have been getting up to date in literary genres such as detective fiction, fantasy, scifi and horror.

Charlie Vazquez: Latino Rebels founder Julio Ricardo Varela and I discussed this years ago when we first launched Latino Rebels as a blog and Facebook page and coined the #LatinoLit hashtag to group tweets together on Twitter for readers, writers, poets, academics and publishing professionals to locate writers and their works, and it has taken a life of its own. And there’s more coming for that!

Chris Campanioni: I think New York City probably has greater support systems in general, for all sorts of writers, but especially Latino writers and other artists producing art on the fringes. At the same time, it’s kind of a big irony, since New York City is also one of the biggest obstacles for artists who live here, in terms of rent and the cost of living. I think that situation sort of creates a desperation that is actually helpful, or at least that I’ve found helpful, in my work, both as a process and in the content itself. There are a number of Latino-centric bookstores throughout New York City, and Latino reading groups that travel well across the boroughs. Many of the student and faculty-run Latino and literary organizations within the City University of New York’s colleges (Baruch College and John Jay, especially), and Pace University, have been really supportive of my work and of one another’s creative output. If I didn’t teach at these colleges, I would probably feel less inclined to say that support systems for Latino writers are thriving in New York City; but as we all can recognize, “Latino lit” is becoming a thing, even as this thing is hard to define, and I think there will be more humanitarian organizations like PEN America in place, in New York City and elsewhere, by next year or 2017, if only so larger corporate interests can co-opt our literary culture and reap the profits.

Charlie Vazquez: I think that Latinos, like other minority and immigrant groups, have been colonized and taught not to support one another, and this is something that I consciously reject and do the opposite of. If we start sharing resources and introduce the folks who read our work to other writers in our communities, everyone wins! More books read, more books sold, more book deals signed, etc. Period. Publishing is a business. And until we begin increasing awareness of writers and book sales we will all remain right where we’ve been: behind the mainstream.

Corina Martinez Chaudhry: Let me respond as the CEO of the Latino Author and from the perspective of many Latino Authors and their experiences within the writing and publishing industry. There are two huge challenges that many Latino writers face. The first challenge comes from the publishing industry and the second comes from a marketing angle. It appears that the publishing industry overlooks Latino writers because publishing houses are all about the bottom line and they don’t feel that these type of books will sell. There is a myth that Latinos don’t buy books (or enough books to help their bottom line) and the publishing houses tend to lean towards the fact that the overall white American market won’t buy these books. The other challenge in this area is that main publishing houses tend to feel that Latino Authors only write about immigrant stories, which is far from the truth. Sure, many Latino writers do write about this topic; however, there are many Latino writers that write Science Fiction, Murder, Suspense, Romance, etc. This mindset will remain as long as publishing houses continue to mostly publish books from the “white” sector. There are very few Latino writers who have been able to break this myth such as Junot Diaz, Sandra Cisneros, Reyna Grande, etc.

Rich Villar: I’m a poet. In the United States, poetry already fights for space on the shelves of every bookstore from the independent shops to the used bookstores to the giant box stores. So, I suppose that’s a challenge. But there is another sort of conversation and meta-conversation among poets (and writers generally) that bubbles beneath the surface, almost at all times: equity in the literary world. By equity, I mean the notion that a national literature should reflect everyone in that nation, and that means Latin@s should enter the conversation as well. I write about equity. It occupies my thoughts. I’m told all the time it shouldn’t occupy my thoughts. That I should just write, right? Well, of course I should write. But I’m also an activist and an educator. And I am oppositional by nature. So, I think about this stuff anyway.

Nelson Denis: To me, it seems that you write the way you live. In order to write about different topics, just become interested and involved in them. Make them a part of your life. Make them a part of you. Then start writing about them. I think that writing is like sitting in a storm. I just sit and sit, and get soaked to the bone, and get sick, but I keep sitting because that’s all I know how to do, and then one day, if I’m fucking lucky, I get hit by lightning. At this point, I just write the thing that makes me sit in this chair, which is getting harder to do. If I thought about the general public I’d go crazy, which I already am anyway.

Chris Campanioni: I write very fast and like Nelson acknowledges, it is an omnipresent, time-consuming endeavor. I wouldn’t have it any other way and I am often able to write in transit, which frees up my schedule immensely. At the same time, it can feel overwhelming when I find myself in a situation where I have three manuscripts ready to ship off to an agent and I’m already off to the next project. Most writers don’t enjoy the business aspects of writing, what comes after the writing. And I think it’s hard to negotiate the writing schedule around very time-sensitive concerns like agency communications, submissions, and pitch letters. As a rule, at least for literary magazines, I try to set aside one day a week where I take care of submissions for an hour, either before work or after work. That’s the bare minimum: one hour a week. Often, I spend much more time with submissions. These things are important because they build readership and make your work more widely available, but at the same time, they necessarily require so much time, much more time than the actual writing process.

Nelson Denis: I think it’s important to have as broad a life experience, and as broad a reading experience, as possible. Reading is absolutely critical! I believe five years of directed reading will beat the Iowa Writers Conference any day. But it must be conscious, cumulative, retentive, and specifically engineered for the type of writing that you are interested in.

Isandra Collazo : I believe there is indeed a strong literary scene on the Island, as well as different study programs and workshops to help aspiring authors shape their work in the best way possible. Our people in Puerto Rico have a drive to write, and not just within the hidden pages of a personal journal. For instance, they witness different social issues unfolding around them and they have an urge to put their thoughts down on paper; as poetry, short stories, and even song lyrics. A few months ago, I received a gift from a friend who is a poet. It was a collection of poems and short stories, written by several authors and students from a creative writing program offered by the Institute of Puerto Rican Culture, at Museo Casa Jesús T. Piñero in the town of Canovanas.

I mention this because it shows that our writers are supported and encouraged to carry on with the art, even get their works published and presented to the public. A chance like that might seem minuscule for authors with international representation, but for a young writer it is huge. Still, I find that it is hard for new Latino writers to find representation, especially if you write in English, about subjects that don’t exactly cover Latino issues, and God forbid if your main character is a Hispanic female. Of course, this is very subjective.

J.M.: What kind of books do you see as essential or as being what is popular today?

Nelson Denis: On reading… this is a completely subjective list. Also, how do you cut it off… we could all write down 100 books. Probably tomorrow, I would write a different list! That’s how subjective it is. I’ll break it up into 22 ”Latino” and 22 “General” books, in no particular order:

Latino

100 Years of Solitude

Don Quijote

Down These Mean Streets

Mendoza’s Dreams

Platero y yo

Open Veins of Latin America

Los de abajo

La guaracha de Macho Camacho

In the Time of the Butterflies

Pedro Albizu Campos. Las llamas de la Aurora

Before Night Falls

Dreaming in Cuban

Our House in the Last World

Pedro Páramo

Don Segundo Sombra

La vida es sueño

La casa de Bernarda Alba

Marianela

La charca

Niebla

San Manuel Bueno, Martír

El lazarillo de Tormes

General

The Bible

Hunger (Knut Hamsun)

Aesop’s Fables

Grimm’s Fairy Tales

The Upanishads

Aristotle’s Poetics

Magister Ludi

Invisible Man

The Great Gatsby

Old Man and The Sea

The Sun Also Rises

Germinal

Grapes of Wrath

Tortilla Flat

Collected Stories of Kafka

Collected Stories of Edgar Allan Poe

Crime and Punishment

Chekhov’s Short Stories

Interpretation of Dreams

Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious>

The Art of Dramatic Writing

How to Win Friends and Influence People

Isandra Collazo: So there’s a big community of writers, huge perhaps, as well as readers. But the question is; what do Puerto Rican people like to read about these days? This is taken from Metro PR and IndicePR, last year’s best sellers in the Island:

Bajo la misma estrella, John Green

Four, Verónica Roth

Will Grayson, John Green

Dork Diaries 7, Rachel Renee Russell

An Abundance of Katherines, John Green

Divergent, Verónica Roth

The Death Cure, James Dashner

Yo soy Malala, Malala Yousafzai

Pensar rápido, pensar despacio, Daniel Kahneman.

(And I’m not going to disappoint you,) 50 Shades of Gray, E.L. James

I mean, what is Puerto Rican literature? Books exploring our history, our colonial status, our political circus, and our national identity crisis? Poems about tragic love stories and childhood traumas? What do people want? Or better yet, who’s/what is our target market?

And why are big bookstores closing down? (Bye bye Borders, bye bye Beta Books Cafe).

Personally, I’d love to get to read more Nuyorican literature, and books from Latin authors living abroad, where they share those new experiences and have another perspective. Although there is some support, authors in the Island need to feel free to write about other subjects, for they are afraid. I was afraid. I am still afraid.

J.M.: Isandra, could you elaborate more on the challenges faced by female Puerto Rican authors? And how does everyone feel about being constrained by subject matter that may be “expected” by a Mexican, Puerto Rican, or Brazilian author?

Isandra Collazo: Definitely. I don’t mean to sound like a butthurt female, but it is often expected of me to write of the following genres:

Fiction: YA/Coming of age; Romance (all categories)

Non fiction: How to’s/DIY; Fashion and beauty (mostly articles); Memoirs; Spirituality

And since I am Christian, leader of two ministries, guess what; I am expected to write only about Christian topics, and will be attacked and judged for anything out of the “ordinary.” (Can’t wait for what will happen when they read my novel. *Sigh* bring it… ) In other words, I’m supposed to hold back in many aspects. That said, let’s bring in the fact that I am Latina and my fiction novel (concerning the struggles of expats and refugees) has a Latina main character running around the Netherlands and not the barrio. Sounds a little odd, perhaps?

What’s more common:

In a bold search for new life experiences, the beautiful and ever-independent Isabel Alvarez leaves her cozy American Dream to…

In a bold search for new life experiences, the beautiful and adventurous Katie Smith leaves her American lifestyle to…

See, I felt obligated to say that Isabel was an independent woman who left her American Dream, or basically a woman who left her immigrant success story. Whereas a girl named Katie Smith already gives you the idea that she doesn’t need such adjectives. Am I falling off the point? I feel that my challenge is not because I am Latina, but because of the subject I write about and how I portray my characters. I kind of leave whites in a shadow, except perhaps for one character, throwing all the stereotypes on them while I attempt to bring forth many other cultures and ethnicities.

Chris Campanioni: But you know, as Nelson sort of suggests, this kind of stuff happens all the time and the best thing to do is put your nose in your notebook (or laptop) and keep writing. Writers have egos and they like those egos stroked, even and especially if it’s the other writers doing the stroking. The literary world can often feel like a big dick-swinging contest (and the metaphor is not without its gendered implications: by and large, women are ignored but that, too, is improving) where writers would rather antagonize one another than coordinate, collaborate, and create a meaningful dialogue. The basis of this, I think, is some manufactured idea of “fame” in the world of letters, whereas several others are writing because we have to survive. Write or die.

J.M.: Would you all say the literary world is eating alive it’s most promising writers?

Chris Campanioni: I think the literary world is filled with sociopaths—like any other industry—except in the literary world, it seems somehow worse because this is art that is at stake, not making a profit for some stranger you’ll probably never meet. Anyway, I agree with Charlie’s point here, and Latinos, perhaps more so than other minority groups, tend to polarize one another through various lenses (whether linguistic, thematic, or even appearance: “They don’t look Latino enough to me.”). I mean, in the end it can sound quite funny but of course it is anything but. The issue with “Latino lit” is only that Latino lit as a genre is so sprawling; Latin America is comprised of 21 countries, each with very distinct traditions, interests, histories, slangs and dialects. But readers and writers and editors and agents—some of whom are Latino, too—expect a formula, and very often, ignore or criticize the work if it doesn’t meet these expectations.

Rich Villar: Consider this: every year, institutions purporting to speak as national cultural arbiters spend their time doing things like reviewing books, or having conferences, or doing book clubs. And every year, somehow, they manage to miss Latin@ authors. The New York Times managed to produce an all-Anglo reading list this past summer. So, as writers of color, of course we must push back against it. The internet is good for that. It’s a democratizing space: Charlie brings up Julio Ricardo Varela, the #LatinoLit hashtag, and Latino Rebels. I have been fortunate to be able to champion my causes on high-visibility online spaces like Latino Rebels, George Torres and Sofrito For Your Soul, and Denise Soler Cox and Project Enye. I’ve also worked with Tony Diaz and Librotraficante, in an effort to reverse book bans (yes, we still do that here), as well as the trend against ethnic studies in the United States.

J.M.: What about the content itself? How do we stand out?

Rich Villar: Scott McCloud in Understanding Comics lays out a useful graph documenting the possibilities for visual iconography, from pure text to pure representation to pure abstraction. I read this book in high school, reread it in college, and it changed a lot of how I view my own work as a poet. I started looking to the visual, how lines are shaped, how breath is represented on the page. Which then led me to explore certain poetic theories: William Carlos Williams and the variable foot, E.E. Cummings and Papoleto Melendez and concrete poetry, the idea of poetry being a visual art. Which, in turn, led me into Sekou Sundiata and Tracie Morris and Edwin Torres and the possibilities for spoken sound as poetic line.

In poetry, there is music, there is silence and sound juxtaposed into lines, and of course this translates most easily as theater. There is Shakespeare, of course, but there is also Ntozake Shange and Reg E. Gaines and Lemon Andersen and Rock Wilk and so many theatrical poets doing what they do. And what of prose? Look—if you read Junot Diaz or Ana Castillo or Luis Urrea or Sandra Cisneros, you can literally read color, texture, movement. So it’s no surprise when these books become movies, and poems become plays—the text so naturally lends itself to the visual. (And Shange invented the form to describe it—choreopoem.) And of course, none of this is an accident. We live in a cinematic culture, an eyes-first culture, a culture of instant information, and French New Wave style jump cuts and extended camera shots, and fast pacing and editing. Of course our literature will reflect that. Let’s hope we’re producing a generation of writers who are self-reflective enough to recognize the commonalities in the critical vocabulary among these genres. What to show and what to conceal in service of the narrative. Let’s encourage writers to be brave enough to cross into the visual arts entirely, and visual artists onto the page. It would be a return to the root. Is the Latino community equipped to lead it? Of course they are. But the thing to realize is that text and visuals and sound have always been interrelated. We’re only now reawakening to their existence on the same iconographic plane. And incidentally, Pablo Neruda read to 100,000 people on more than one occasion. Is it too much to ask for a Latino poet to fill a soccer stadium?

J.M.: There are structural challenges as well as internal ones, then? And it sometimes falls into place along tribal lines, no?

Nelson Denis: Latino Lit in the US is in a state of atherosclerosis. Nothing is moving. The “icons and shibboleths” are all in place:

Down These Mean Streets

Our House in the Last World

House on Mango Street

In the Time of the Butterflies

Dreaming in Cuban

Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao

Bless Me, Ultima

I see a pattern here. If you break down our Latino rainbow (Mexican, Puerto Rican, Cuban, Salvadoran, Dominican, Guatemalan, Colombian, etc.) you’ll note that one and maybe two from each country (only 4 countries) make it into the above group. The publishing industry is so myopic, they think so categorically, that if a new Latino-American writer offers a story that is deeply-rooted and narratively circumscribed by their country of origin, the junior acquisitions editor says “oh, we already have one of those” and finds an excuse to pass.

Meanwhile the senior acquisitions editors are throwing the big money at Isabel Allende, Carlos Ruiz Zafón, Raul Alarcón (U.S. hybrid, but “writing Peru”)—all Latino authors from outside the US, which shows a blatant snobbery and racism: European and South American authors are “high brow,” but US Latino authors are ghetto underlings, and couldn’t possibly have anything to offer.

The same thing is happening with Latino film directors: practically all Mexican, born & bred over there, not here.

Rich Villar: I think this is a destructive mindset that is born from a marginalized, colonized perspective. The Oppression Olympics. The Authenticity Maze. The relative slice of the literary representation pie is not large enough for Latinos to start fighting over. I don’t know which Latino group “dominates” who. (The question makes us sound like we’re all battling for literary supremacy in the octagon.) But, here’s what I do know: Magdalena Gómez and Raúl R. Salinas were friends. Miguel Algarín and Jimmy Santiago Baca as well. Throughout his career, Martín Espada has been allied with and championed by Chican@ writers from Luis Urrea to Gary Soto to Luis Rodríguez to Sandra Cisneros. And Pietri and Papoleto and the Nuyorican poets were honorary members of Jose Montoya’s and Esteban Villa’s Royal Chicano Air Force in California. In other words, we have always been our most successful as a literary movement when we make an inclusive Latinidad, when we seek out comrades and commonalities and write ourselves into a soulful and (yes!) legendary existence. This is why the Acentos Review literary journal does well, not to mention poetry workshop spaces like CantoMundo and La Sopa NYC.

Chris Campanioni: Good writing will always be the writing that has been lived in. Another way of putting this is to admit the obvious: write what you know, but many writers, young and old, forego life experience for an MFA program and crippling loans. In this way, our topics are inevitably Latino because Latino represents multitudes, sort of like my man Martí said: “Yo vengo de todas partes, y hacia todas partes voy.” Do we follow orders and the rules of academia or the broader literary culture while forgetting our own personal stories? Or do we use the specific pressures and expectations Jonathan suggests are in place for Latino writers as an opportunity to circumvent or re-evaluate them?

Corina Martinez Chaudhry: Unfortunately, Latinos in this country are seen as being at “the bottom of the rung” due to the prejudice and ignorance of decades of stereotyping this group. We are seen mostly as people who clean houses and are only good for gardening, which although it is a hard-working core group, the majority of people look at this as demeaning work. In addition, you see the statistics of Latinos not graduating from high schools and many gangs being associated with Mexicans or Latino groups. Americans, especially white Americans, paint us all with the same brush stroke.

How do we change this? It comes from us continuing to ensure that we as well as our offspring become educated, and we continue to fight to get into the mainstream. This comes from all Latinos working together to make this change because no matter how much infighting there is between our Latino groups because we are from different countries or from different Latino Sectors, the mainstream lumps us all into one. We haven’t yet gotten to the cohesiveness that the blacks have been able to achieve in this country.

J.M. Ricardo, so many of us are Caribeños here, give us the Mexican perspective.

Ricardo Félix Rodriguez: It is characterized by hierarchies, bureaucracy, institutions. Mexico remains a centralized country, therefore resources are concentrated in the capital city. Writers from Mexico City act like if they were the only source of literature. Publishers bet on big names so it is very common for northern writers to seek to write in english. It is also very competitive; there is a belief that only foreign (mainly European) literature has quality and you as a Mexican should not try to be original. I guess you can say it is the culture of “crab” when a crab tries to get out of the bucket and another one pulls him in until it falls.

J.M.: Is there any government support?

Ricardo Félix Rodriguez: There is support but there are several points against. You have to adapt your writing to a particular literature whether local or regional. Universal themes are rarely allowed. Groups of artists are usually privileged when they have a relation with coordinators. The same writers are competing for the same grants and awards but not able to make a living by selling their books. If Mexico is a country with “poor reading” in the north the crisis deepens. There is a perception that art is an obligation of the government to provide.

J.M.: How is the community of writers though?

Ricardo Félix Rodriguez: There is a community of writers trying to do things differently but writers tend to be competitive here. I would say that the writer here is individualistic, jealous of his work. I think the best talents are not yet known in independent publishing, underground literature, drowning their poetry in a glass of beer.

J.M.: David and Ricardo, what can individuals or local groups do to increase opportunities for up-and-coming authors?

Ricardo Félix Rodriguez: I see it as some kind of reading crisis. People are not used to reading; we need to find the way to promote reading. Through education, raise the cultural background of the average citizen.

David Caleb: In Puerto Rico, in order to increase opportunities for up-and-coming authors, there needs to be an educational revolution starting from the way up and the way down at the same time. First and foremost, the Department of Education must be depolitized. It needs to be flattened and entirely professionalized. There simply is no other way. Teachers need to be sent to reading seminars and there should be a reading course in all grades.

We see close to no state aid whatsoever in our endeavour. Most of our boom has been subsidized by ourselves. Most of the people publishing books are self-managing themselves. It’s a pity, in a way, that such an amazing body of work cannot be entirely supported by the government. However, we have grown used to it. Puerto Rican writers are used to being disenfranchised and orphaned.

That’s as far as the government goes. Now there is a small grassroots movement (everything in PR is small and grassroots) of theatre producers using material from Puerto Rican narrators and poets to make theatre, but this effort needs to be exploited much more. Also the literary scene is too concentrated in San Juan.

J.M. It seems like the problems both inside and outside the US are as much social as they are financial. There is the problem of a lack of interest in reading alongside the problem of marginalization in the media and/or geographically. What solutions might there be?

Corina Martinez Chaudhry: The second biggest challenge that many Latino writers face is marketing their books once they are published. I find that many authors don’t even have webpages or understand much about the internet and how to market their books through this venue which is the greatest tool in this day and age. Many do not understand Search Engine Optimization (SEO), or Google Analytics and how to make these particular tools work for them. By accurately understanding these tools, the way an author writes would not necessarily be a challenge once a writer figures out his or her niche.

Rich Villar: What is it Dead Prez said? “When you bringing it real you don’t get rotation/unless you take over the station.” What’d Jay-Z say? “I’m the new Jean Michel/surrounded by Warhols.” Opportunities exist for writers all over, if you search for them. Grants. Fellowships. Speaking gigs. Freelance writing and editing. That sort of stuff. Here, in the States, that kind of support is not always present, certainly not the same way it’s present in other countries. Here, it’s not an easy life. You have to hold down a 9-to-5 most of the time. At the same time though, I also try to be wary of those places of support that require you to be content inside a particular box, or to be beholden to a particular power structure. That’s why I identify with the hustlers among us poets; yes, we create good textual work, but we also find new ways to express it—on stage, in movement, in visual art, in music, in multiple genres. That’s where my work is taking me. And the freelance life is not easy, but I don’t answer to anybody but my mirror.

I’ve noticed a tendency among younger writers to put the marketing cart before the writing horse. I think the biggest mistake any writer can make is to start thinking about a platform for themselves, or where they’re going to tour, or how much product they’re going to move, before they’ve ever set pen to paper or finished a full poetry manuscript or fleshed out their novel or their memoir. There are so many directions to take within the world of social media, but none of it matters unless you actually have something to say.

These are questions about finding audience, not finding voice. I would tell writers who come into my circle to read and listen and absorb and learn for as long as humanly possible. And then, they should write voraciously and mess things up and take chances. And then, once they have a style they feel their strongest selves in, once they have built a genuine vision for the world, they should write the kinds of prose and poems that scare the shit out of the powerful and thrill the everyday reader. And then they should open up Twitter accounts. It’s needed. This is an age in which Latinos are being banned and deported and threatened and killed off. We need the kind of visibility that changes hearts, not one that simply turns heads. Good literature, followed by good marketing of that literature, will provide that.

J.M.: In this age of such rampant exposure, where on the one hand, access to millions is at anyone’s finger tips, and on the other, the most important access, the access that helps you make a living are still shut off for the vast majority of people, how do we achieve equity, not just amongst Latinos, but other groups as well?

Rich Villar: The structural battle for cultural equity also leads to some specific artistic battles. Following in the tradition of Sterling Brown and Piri Thomas, I insist upon the truth of vernacular speech and Spanglish in my writing. I follow the transformative prose tradition of James Baldwin, the philosophical underpinnings of Nuyoricanism and the Black Arts Movement, and the truthtelling poetic traditions of Whitman, Neruda, Lorde, and Espada. I believe art is a vehicle for change, and I believe poetry humanizes. I also believe that poetry rooted in those liberatory urges, when taught to teens and young adults as part of a liberational pedagogy, helps form students’ notions of citizenship and citizen action. The cynics will tell you that poetry makes nothing happen. I am telling you, poetry creates possibility out of impossibility. It makes the invisible visible. And it turns cynical people —teens, especially—into leaders. I am eyewitness to that fact.

I’d like to think we’ve gotten better, but we squabble like any other family. My pet peeve among Latino authors is the silencing of others, the shutting down of debate. I think more gets done in any group dynamic when we’re honest about our feelings, no matter how detrimental it may seem at the time. I hate scenes generally. I hate people who think they’re better than others. And I hate grudges. If I have to sit and worry who I might be offending by saying something, or if I have to studiously avoid someone because he or she’s got some beef with me or someone close to me, it just complicates my life unnecessarily. And worse—it has nothing to do with writing. I can name these things honestly because I have also fallen prey to them.

Corina Martinez Chaudhry: Unfortunately, the main publishing houses are based in New York, so for those authors that live in Mid America or in the West Coast, there are some challenges in getting to know who is who in the industry. The best way of course is to network and make connections within the publishing industry and that can be done by understanding the web and marketing yourself effectively. This is also a way to market yourself in other countries and locations. There are a few support systems that can be used for Latino Authors such as my site, The Latino Author, La bloga, Azul Bookstore in New York, Martinez Book Store at Chapman University in CA, Las Comadres, or the Latino Literacy which assists in giving out awards to Latino Authors in various genres. Connecting with these organizations can provide great support.

Chris Campanioni: Social media is one way in which writers can make these distinctions outside of their work but also adapt their work for new forms. The YouNiversity was originally conceived as a year-long digital mentorship for new era writers, a reaction to the recycled curriculum and check-listed objectives of many MFA programs in the United States and Europe. We’ve been really conscious about devoting a great deal of instruction to the powers—and pitfalls—of curating your digital presence as an author, as well as the work you produce, and finding interesting and exciting ways to present this material in new mediums by really taking advantage of capabilities that certain mediums afford us. The emphasis on several different forms of accessibility, audience contribution, and increased agency is the foundation for the kind of art that will become the eventual norm in the twenty-first century, so it’s not surprising that we urge our students to think about questions of reader inclusion and interaction from the opening weeks of each YouNiversity program. But to really turn social media into a tool for creativity instead of just regurgitation and masturbation, the cultural norms for social media have to change. That kind of work begins with authors like us, who need to start thinking about social media as another mode for creativity, not just for marketing.

J.M.: I have enjoyed this conversation immensely everyone, and to close things out, I want to know what you think is the future of Latino Lit, starting with Nelson.

Nelson Denis: So I see the “future of Latino lit” as one that is highly eclectic: still forcefully Latino, but in surprising, mercurial, even devious ways. We can’t lead with just one punch anymore… We need narrative surprises from multiple tropes, from all directions, and all at once. Latino Kurt Vonneguts and Henry Millers and Hunter Thompsons that defy easy categorization. I’ll offer one example: The Miniature Wife, by Manuel Gonzales. There is a Latino soul in those stories, and it adds to a sense of dread and paranoia… But he uses it like a blackjack. By the time you realize what’s hit you, Gonzalez has made off with your wallet and your pants. That motherfucker can write.

Between the snobbery of the latest Isabel Allende doorstop of a novel, and the mummified ruins of Mango Street, there’s no room left… Unless you make room for yourself, with a punch they never saw coming.

A new genre/sub-genre/hybrid genre or mash-up… A strange dystopian anti-hero… A shocking re-configuration of ancient Latino folk tales… Anything that knocks them off balance. Anything that makes them suspect, if only subliminally, that they’re abysmally stupid (which they are), and you know something that they don’t—which you do, because you are Latino.

Corina Martinez Chaudhry: The future of Latino Literature, as I see it, is not only in the hands of Latino writers ensuring that good “stuff” is written, but also in being able to work together to change the status quo in this country about how we are perceived. Not to bring politics into the mix, but just look at the temperament of Trump followers and how he has risen in the polls because he began his campaign on bashing immigrants (who we all know means mostly Mexican or those coming from Latin American countries). He was not targeting the Canadians or those coming from “white” nations.

That is why publishers in the industry still have this narrow-minded view that Latinos don’t read or buy books. They think the majority of us aren’t interested in reading or education. Partly, the publishers don’t want to change what has been working for them to make their business successful. It’s not that we don’t buy books, but there are not true statistics of who really buys books. Someone writes about Latinos not buying books and unfortunately people see it as being true. Also, with so many mixed marriages in this country, you don’t even know who has Latino DNA so how would they really know? I was reading an article on PEW Hispanics about how Latinos perceive themselves in this whole mix of nationality and it was very interesting. Some don’t even claim to be Latinos because of how they were brought up although they are very much Latino. So where do these persons fit in those statistics?

There isn’t just one answer to where Latino Literature goes in the future, but I have a feeling that it’s going to be a long climb for most of us. It is a grassroots effort that is needed—beginning with writers such ourselves—to get the masses to change their thinking. How do we do this? First we write good literature, then we support each other to get to the next step whatever that may be, then we become great at spreading the message, and then we put pressure on the main publishing houses to begin promoting some of our great writers or we help other Latinos to start our own publishing houses and support each other. With so many millions of us in this world, we still continue to let “white” Americana tell us who we are.

I am optimistic though. I think that today we have so many Latinos who are successful, and hopefully with that it will cause some “reverse thinking” about who we are as a people overall. It is about not only loving our culture and our language and all that good stuff, but being smart enough to use it to our advantage and work together to get to the mainstream. If we don’t do this, then the future of Latino Lit will remain in the shadows as it does today.

Rich Villar: I would love for Latino Literature not to need to exist. I would love for the United States to begin implementing a pluralistic, multicultural vision of citizenship and for the stories of Latinos to simply take their natural place in the nation’s cultural conversation. Our numbers are, after all, expanding. But realistically, we live in a time when politicians are openly calling for our expulsion and exclusion from the nation. And people are actually taking them seriously. And so, a literature of resistance must emerge. A literature so undeniably good, and human, and innovative, and united, that it would serve as a collective shout and bulwark against our disappearances. If we receive “institutional” support for those efforts, if the mass media chooses to see us and feature us, I think we should welcome it. But if they don’t, or if they compromise us for simple visions of marketing dollars, I think it’s our responsibility to use as many new media and alternative models to support ourselves and demand our places, without permission or translation.

Chris Campanioni: I believe Latino lit—or at least Latino writers—will begin to get more representation, not only in the form of the year-end “best books of …” list, but also on the daily publication level. More editors of more magazines will be looking to publish Latino voices because they don’t have a choice. The quality of our writing, the diversity of our writing, and the sheer amount of Latino writers actively writing today will make the issue of lack of representation seem antiquated in five years. I think we might all agree, Latino writers have much bigger issues to tackle.

David Caleb: I want the literature of my country to head towards uncharted horizons. As a personal project, I am training students in non-fiction queer writing, in order to rescue the history of our island’s queer community, its struggles, its literature, art, music, political activism, and general history and culture. I am also training pansexual and lesbian female writers who will bear the torch in that particular niche. I want a future where every single genre is represented in the island. But more importantly, I want an island of readers. We will rescue and create readership.

Isandra Collazo: This may be a risky answer. But just like Puerto Ricans have been able to stand out worldwide in music, sports, art, cuisine, I guess would also like to see best-selling Puerto Rican authors on the New York Times best-seller list, in genres like fantasy and SciFi, romance, erotica, and fiction in general but perhaps less on the political subject, less colonial status discussion, and less of the past. I want to jump out of la carreta and get on a space ship, looking to the future. I’m not saying those subjects don’t matter, they are our daily bread. But I suppose I want Puerto Rican writers to be known for their creativity and incredible, explosive imagination, fantastic worlds and unforgettable characters, not just deep research.

A friend of mine who is an Assyrian artist told me that cultural or historical pride was meaningless if one didn’t create something. In other words, what’s the point of shouting, “Yo soy boricua, pa’ que tu lo sepas” (I am Puerto Rican, just so you know!) if I can’t add anything else to it? I understand we are on an eternal search for identity (I am, always!) but as a Puerto Rican writer, I want to put my Puerto Ricanness on diverse scenarios and worlds, not leave it in the comfort zone or where it feels at home.

—by Jonathan Marcantoni

.

Jonathan Marcantoni is a Puerto Rican novelist and former Editor in Chief of Aignos Publishing. His books Traveler’s Rest, The Feast of San Sebastian, and Kings of 7th Avenue deal with issues of identity and corruption in both the Puerto Rican diaspora and on the island. Along with his solo novels, he also co-wrote, with Jean Blasiar, the WWII-fantasy Communion. He is co-founder (with Chris Campanioni) of the YouNiversity Project, which mentors new writers. His work has been featured in the magazines Warscapes, Across the Margin, Minor Literature[s], and the news outlet Latino Rebels. He has been featured in articles in the Huffington Post, El Nuevo Día (Puerto Rico), El Post Antillano, and the Los Angeles Times. He has also appeared in several radio programs, including NPR’s Fronteras series, Show Biz Weekly with Taylor Kelsaw, Nuestra Palabra: Latino Writers Have Their Say, The Jordan Journal, Boricuas of the World Social Club, and Wordier than Thou. He holds a BA in Spanish Studies from the University of Tampa and an MH in Creative Writing from Tiffin University. He lives in Colorado Springs.

.

David Caleb Acevedo (San Juan, 1980). Writer, painter and translator. His books include Desongberd, Cielos negros, Diario de una puta humilde, and Hustler Rave XXX: Poetry of the Eternal Survivor. He is pansexual and lives with his husband and three adorable cats.

David Caleb Acevedo (San Juan, 1980). Writer, painter and translator. His books include Desongberd, Cielos negros, Diario de una puta humilde, and Hustler Rave XXX: Poetry of the Eternal Survivor. He is pansexual and lives with his husband and three adorable cats.

.

Chris Campanioni‘s “Billboards” poem that responded to Latino stereotypes and mutable—and often muted—identity in the fashion world was awarded the 2013 Academy of American Poets Prize, and his novel Going Down was selected as Best First Book at the 2014 International Latino Book Awards. He edits PANK and lives in Brooklyn. Embrace the Death of Art.

.

Corina Martinez Chaudhry was born in New Mexico but has lived in California most of her life. She grew up in the San Joaquin Valley throughout her high school years, but then made the transition to Southern California where she now resides. Her maternal grandparents were from Chihuahua, Mexico; however, her grandmother was half Basque (Spanish/French). Her paternal grandparents were of Mexican and Native American descent. She graduated from Vanguard University Magna Cum Laude with a bachelor’s degree in business and a minor in English. In addition, she has completed a Water program through the California State University of Sacramento, alongside a Management Certification Program through Pepperdine University, and currently manages The Latino Author Website.

Corina Martinez Chaudhry was born in New Mexico but has lived in California most of her life. She grew up in the San Joaquin Valley throughout her high school years, but then made the transition to Southern California where she now resides. Her maternal grandparents were from Chihuahua, Mexico; however, her grandmother was half Basque (Spanish/French). Her paternal grandparents were of Mexican and Native American descent. She graduated from Vanguard University Magna Cum Laude with a bachelor’s degree in business and a minor in English. In addition, she has completed a Water program through the California State University of Sacramento, alongside a Management Certification Program through Pepperdine University, and currently manages The Latino Author Website.

.

Nelson Denis is the author of War Against All Puerto Ricans (Nation Books, 2015). He served as a New York State Assemblyman, and was the editorial director of El Diario/La Prensa in New York City. His screenplays have won NYFA and NYSCA awards, and his editorials received the “Best Editorial Writing” Award from the National Association of Hispanic Journalists.

.

I.C. Rivera is an enthusiast of travel, international cuisine and everything exotic. She’s passionate about humanitarian work, and often volunteers at shelters and facilities for asylum seekers. Through her literary work, she aims to raise awareness on different social issues, by writing intriguing and exciting novels with a multicultural flavor.

.

Ricardo Félix Rodríguez (Sonora, México 1975). Writer and psychologyst. His books include The surreal adventures of Dr. Mingus, Asgard: a Saga dos nove reinos, There is No Cholera in Zimbabwe, and The Other Side of the Screen (contemporary writers of Poland).

Ricardo Félix Rodríguez (Sonora, México 1975). Writer and psychologyst. His books include The surreal adventures of Dr. Mingus, Asgard: a Saga dos nove reinos, There is No Cholera in Zimbabwe, and The Other Side of the Screen (contemporary writers of Poland).

.

Charlie Vázquez is an author and the director of the Bronx Writers Center. He served as New York City coordinator for Puerto Rico’s Festival de la Palabra for three years and has just completed his third novel.

.

Rich Villar is a writer, performer, editor, activist, and educator originally from Paterson, New Jersey. His first collection of poems, Comprehending Forever (Willow Books), was a finalist for the 2015 International Latino Book Award. He maintains his personal blog at literatiboricua.com and is a contributor to Latino Rebels and Sofrito For Your Soul.

.

.