In this piece, Moore explains how Ted Morrissey’s postmodern work on Beowulf has opened his mind to fresh interpretations. Far from thinking everything about the poem has been answered, Moore shows, first, that when a critic approaches a work with new eyes the result can be invigorating, and second, that the trauma enacted in these old verses have relevance to our world. —Jeff Bursey

.

Not having studied Anglo-Saxon since grad school, nor having kept up with Beowulf criticism in particular, I’ll take Ted Morrissey’s word for it in The Beowulf Poet and His Real Monsters that most recent criticism on the Anglo-Saxon poem remains fixated on old-fashioned philological study. While these textual issues are important—especially when one’s interpretation hinges upon a proposed emendation or the accurate identification of the dialect of a certain word—Morrissey’s illuminating monograph demonstrates the advantages of bringing newer critical strategies to bear on the poem, especially “postmodern” ones that might seen incompatible with this premodern work. Looking at Beowulf through postmodern eyes fosters a greater appreciation of the craftsmanship and subtlety of this masterpiece.

For example, one the earliest theorists of postmodernism, architecture critic Charles Jencks, argued that po-mo works are characterized by “double-coding,” whereby the artist appeals to both popular and elite audiences by encoding for the latter group subtle allusions, references, and ironies that will probably go unnoticed by the larger popular audience who focus on the more obvious and appealing aspects of a work. In his essay “What Was Postmodernism?” (electronic book review, 2007), Brian McHale gives as an example animated movies like Aladdin, which “appeal to children through slapstick and cuteness, and to their parents through pop-culture allusions and double entendres that go right over youngsters’ heads.” Beowulf strikes me as a deliberately “double-coded” work, with exciting fights scenes that would delight the scop‘s mead-muddled audience, but at the same time encoded with theological and political issues, intertextual references to other works, and some dazzling wordplay for the benefit of the connoisseurs and intellectuals of his time. Double-coding is also in effect as the poet ostensibly tells a tale set in Denmark and Sweden in the sixth century but that is also (if not really) about England in a traumatized period several centuries later, a transhistorical strategy that would probably go over the heads of the tipsy masses but would not be lost on the more sober thanes in the hall. The popular aspects of a double-coded work will always appeal to a larger audience; Howell D. Chickering Jr. speculates that “Beowulf’s tragic third fight with the dragon was more frequently read than his earlier adventures, since folio 182, where this adventure begins, is quite worn out” (Beowulf: A Dual-Language Edition [Anchor Books, 1977], 246). In contrast, Hrothgar’s serious sermon on pride (lines 1700 ff.) shows little sign of wear.

Postmodern works also flaunt a heightened self-consciousness about their status as artificial literary creations, metafictionally drawing attention to the artist behind the work. No one would mistake Beowulf for a chapter in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, partly because the poet frequently draws attention to himself and to his artistry. On a half-dozen occasions, the first-person “ic” pops up to remind the reader that the tale isn’t telling itself, but is rather a dramatized reconstruction of what the scop has only heard. The scop is self-consciously aware that he is performing his story, not merely reporting it, and highlights this process at line 871, the morning after our hero’s first encounter with the monster Grendel. The anonymous author self-consciously introduces his stand-in into the proceedings, whereupon this wordsmith

found new words,…..bound them up truly,

began to recite…..Beowulf’s praise,

a well-made lay…..of his glorious deed,

skillfully varied…..his matter and style. (trans. Chickering)

Suddenly the reader realizes the previous 870 lines have not been a historical account of Beowulf’s actions but a fanciful re-creation—a literary performance; the poet, having “unlocked his word-hoard” (l. 259), has armored himself with words to perform a glorious linguistic deed to rival if not outdo Beowulf’s wrestling match of the night before. For the story of Beowulf’s deeds, you can read the Cliffs Notes; the poem is a performance of the story, a showy display of the poet’s wrestling match with words in which he emerges triumphant. (Beowulf only tears off an arm.) Look at me, at my prowess, the word-warrior proclaims, not at Beowulf, whose own later account of his fight with Grendel (lines 2069 ff.) is deliberately bland in comparison. One of the few interesting things about Robert Zemeckis’s comically crude film version of Beowulf (2007)—aside from the golden splendor of Angelina Jolie—was Beowulf’s postmodern awareness that he was the protagonist in a work-in-progress to be called The Song of Beowulf.

The poet’s innovative, unconventional use of words is another feature associated with postmodernism, as Morrissey argues in his second chapter, and which he goes on to align with the obsession with diction that trauma victims display. I was previously unaware of trauma theory, but Morrissey argues convincingly that this branch of postmodern theory shines new light on several murky aspects of the poem, on what some readers call its disjointedness and downright weirdness. Beowulf enacts on both a formal and verbal level the effects of trauma on a people (and on a gifted poet) subjected to centuries of warfare, sickness, and disorder, resulting in a poem closer to nightmare than elegy. Morrissey shows how other postmodern strategies illuminate the poem, and respectfully suggests these new approaches can supplement, not supplant, the more traditional philological approaches. Those earlier approaches have for too long treated Beowulf as a period piece, but these new approaches give the lay a startling relevance in the 21st century: I am writing this at the end of 2012, after the quick succession of Hurricane Sandy, the slaughter of children in Newtown, Connecticut, and fears of going off a fiscal cliff have somewhat traumatized Americans—who are not as bad off as the Anglo-Saxons of the Dark Ages, to be sure, but are now in the appropriate mood to appreciate the traumatized world of Beowulf.

—Steven Moore

.

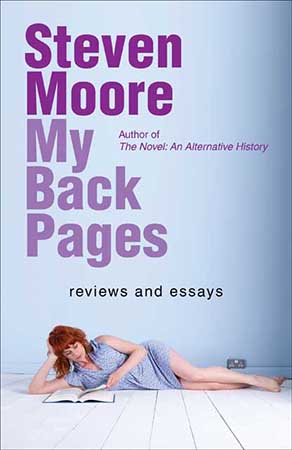

Steven Moore is the author of the two-volume study The Novel: An Alternative History (2010, 2013), as well as several books on William Gaddis. His new book, My Back Pages: Reviews and Essays, is just out with Zerogram Press.

.

.