.

Luxembourg Findel Airport

Old Findel airport in Luxembourg.

Old Findel airport in Luxembourg.

Findel: To find. Who? Alone, no longer here, not yet there. A threshold. Am I coming or am I going? As in Findelkind? Lost? No. Airport: a door in & through the air. I find myself at the airport. For years it meant yearning: watching the planes leave, wanting to leave. Hardly able to see over the balustrade of the old Findel’s flight deck. Later, walking over the warm tarmac to the first plane: Madrid via Bruxelles. Then London. Then New York. Departures. Arrivals. Returns. Systole/Diastole of exile. Circling a receding childhood from high above: farms, fields, cattle, fences. An expanding city. From above: the Grund – der Abgrund, the abyss. Off-rhyme with the Grand Canyon. Airplane dreams. Portage of plain paper reams of writing ferried between continents. Nothing to declare. But this: I love to arrive. I love to leave. It is the same. It is different. The continents no longer drift, therefore we have to. Dérive. Départ. Décollage.

.

Remembrance Day In Patton-Town

I had just returned from New York, was still jet-lagged, when my mother sent me to buy four pork chops at the butcher’s on Main Street. Despite the tiredness I had not objected, indeed, I was looking forward to stroll through the town of my youth, hungry to hear the mamaloshen, Letzeburgesch, and get a sense of what may or may not have changed in Ettelbrück. I walked down the Avenue Salentiny, hung a right at the Grand-rue, turning my back to the now decrepit and desolate Klinik Dr. Charles Marx where my father had worked for many years, crossed the street, passed the Pensionat de Jeunes Filles and a little further on, just where the grand-rue was at its narrowest, I found the butcher shop and entered.

It was shortly before noon and a long line of housewives waited to be served, so I overheard much small talk, mainly about the warm and sunny weather, a good omen for the festive weekend ahead. I eventually got to the counter, ordered my chops and watched absent-mindedly as the butcher’s wife wrapped them expertly. I had been distracted by a noise, a low rumble coming from outside, but thinking that it was some bulldozer or other construction machine, I paid it no further heed until I stepped outside, saw many people gawking and heard the noise getting louder. I too stopped to listen and watch.

It was a deep metallic rumble that came from the east, the direction of Diekirch, or, closer by, from the curve in the road where the Patton monument stood high up by the edge of the bridge that crossed the river Sauer. For a second I flashed back to a day in 1956 when I was walking to grade school with my friend, the baker’s son, and we were gloomy for having overheard the news our fathers had listened to the night before: Russian tanks had invaded Hungary, were fighting in Budapest crushing resistance to the Soviet government. We two ten year-olds knew that it would take those tanks only 3 weeks to cross over from Hungary and invade Luxembourg. What I saw coming from the East and making such a clattering racket (instantly familiar from the movies) were indeed tanks — but these were American tanks, as the flags they sported told us, and the people along the streets were waving in that most friendly manner used to welcome liberators.

And then it came back to me: this must be the preparations for “Remembrance Day,” the yearly celebration of General Patton and his army who liberated Luxembourg from the Nazi yoke during the Rundstedt offensive! As a kid this had been one of the great yearly treats, better for us boys even than the Schueberfouer, as we could clamber up on those tanks, slip behind the steering wheel of jeeps and armored personnel carriers, slide down the barrels of long canons and handle various automatic machine guns with the required respect and awe. On the main day of the event, a Sunday, we’d watch the spectacle of a fake battle in the Deischwiesen with paratroopers jumping out of helicopters, storming “enemy positions,” a circus re-enacting of their assault on our town in 1944. During those days we’d try out our high school or movie-learned English on the American G.I.s to buy used copies of Playboy, a magazine our bishopric had banned from the country.

But this was a different time. This was 1968 and I had just come back from a year in the USA, a year in college in upstate New York, a year in which I had seen and taken part in my first anti-Vietnam war demonstrations, a year where some of my friends had been drafted into the army while others had fled to Canada to escape the draft. That spring the biggest and most murderous battles to date had taken place, and President Johnson had ordered the resumption of the full-scale bombing of North Vietnam.

What I saw that day in the Grand-rue in Ettelbrück felt like a complete disconnect, something out of an old black and white movie, a twisted rerun of World War II victory scenes watched in my grand-mother’s “Cinéma de la Paix” a few houses up from the butcher’s on the other side of the street: the same troops my fellow citizens were feasting in the streets of Ettelbrück for having liberated us, were raining down destruction and death on a people in the Far East. Someone’s liberators will eventually turn into someone else’s oppressors? That day the myth that the armies that had liberated us were the incarnation of heroic, selfless good — and could therefore do no wrong — took a deep dent. Not so much the actual fact that Patton’s troops stopped the Germans from capturing the fuel stock-piled near Bastogne and drove them back through the Ardennes. Not those facts — but the mythology that had been made out of those facts. But what is mythology, how do (chosen) facts become a mythology, and why?

Myth, I had learned that very year upon encountering the work and the person of the American poet Robert Duncan — who was to write one of greatest anti-Vietnam war poems the very next year —, the word “myth,” “mythos,” is akin to “mouth,” i.e. myth is the story told, the story that accompanies the ritual action, some action that starts out as, or wants to turn itself into, exemplary ritual. But maybe it is the retelling of the story — whatever it is — that recreates the action that turns the story into ritual and thus self-reflectively creates the myth. Repetition compulsion, running off at the mouth, or maybe more usefully, as another American poet, Robert Kelly, put it: “Saying makes it so.” All too often then, myth without the ritual action, is nothing but the post facto late words retelling, retooling and all too often tempted to beautify, simplify, purify a past action, and becomes thus empty words, alibis, cover-ups. It may not even always be a question of voluntary deceit.

*

My father was weary when my young curiosity wanted to know “what did you do during the war?” He, like so many of those who had lived through it, didn’t like to talk about those days. But he would eventually relent and tell me, us, the family around the dinner table, some fragments of what befell him during “the last war” (which, of course, wasn’t the last war at all, just as the “Great War” was not great at all, as no war ever is — war is a solitary noun, never trust any adjective that is added to it, except the one already embedded in the noun, read widdershins: raw). He would tell how during the war I was born just after (me, my generation, thus, war’s afterbirth?), he, the young intrepid surgeon, used to operate on “résistants” or freedom fighters wounded in skirmishes with the occupying Wehrmacht, late at night and in secret, deep in the bowels of the Klinik Dr. Charles Marx, in the coal room, on the coal heap. A black and white image that has stayed with me, the black coals & the white medical garments and sheets, the image a frozen scene as they stop what they are doing because upstairs or outside a German patrol is heard strutting by. Is this my mythology or my father’s? I hear the marching boots of the German soldiers in a 100 war movies watched in grandmother’s “Cinéma de la Paix.” Not one good German in all those movies, and not one less-then-heroic American GI.

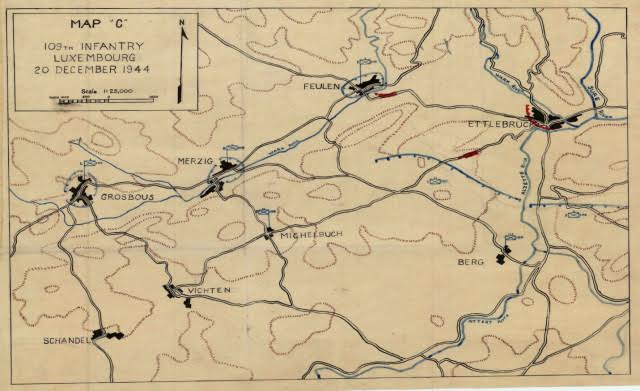

Map of the von Rundstedt offensive.

Map of the von Rundstedt offensive.

But my father’s favorite story was the one where he is out late at night in the forest south of the town. It is a cold and snowy midwinter, and he is looking to score for much needed medical supplies off the Americans. He has stopped and is now sitting around a campfire on the periphery of the US army zone with a few GI’s spooning up their K-rations, when a rather burly uniformed man comes out of the night, clearly a high ranking officer, and greets the soldiers who don’t move from their seats around the fire but greet the apparition back with a quick, laconic hand to the helmet. The tall figure stalks on and disappears into the night, a flash of white briefly visible around the hips, toward where the main body of the army is bivouacked. When my father asks the soldiers who this apparition was, the answer is a single word: “Patton.”

What so fascinated my father was the easy, not to say democratic relationship between soldiers and general: no jumping to attention with mechanically extended arms and a loud “Heil Hitler,” but a nearly egalitarian greeting between soldiers and a commander most recognizable not by insignia, epaulettes, decorations or well-tailored uniform, but by those pearl-handled revolvers flashing at his hips (he probably wore only one, but myth-making memory compounded the figure of the general with that of the gunslinger hero from Western movies usually packing two guns — the famous “peacemaker” colts, no doubt).

No wonder a very few years later the town of Ettelbrück erected a larger than life monument to the hero of the Lundstedt offensive, now safely dead in a car accident, and proceeded to institute the yearly ritual known as “Remembrance Day” described above.

Remembrance Day in Ettelbruck.

Remembrance Day in Ettelbruck.

But, as I think back on all this, another event springs to mind — unrelated on the surface — and yet…. One day — I was in 4th grade — during break, we were on the playground in front of the Ettelbrück primary school. I had recently moved to town and was standing by myself — clearly marked as an outsider, and thus not integrated into any of the groups — when I heard a cry and a song behind me. I turned around and saw 3 or 4 older boys, who had thrown a young kid to the ground and were dragging him along the asphalt, singing: “Eent, zwee, dräi, et as e Judd kapott, huelt e mat de Been a schleeft e fort — One, two, three, a Jew has croaked, grab him by the legs and away with him.” The boy who was the victim of this brutal “game” was indeed a Jewish boy, the son of one of the few Jewish families left in town, Kahn by name. I was horrified, and that nasty little show of stupid, unthinking, petit-bourgeois anti-Semitism, played out by 10 to 12 year old boys less than ten years after the horrors of Auschwitz became public knowledge, has always remained with me as a strange vaccination against the mythology of the good, innocent little Luxembourgers oppressed for years by the a vicious Jew-hating Nazi regime they were unable to resist because of the smallness of the country until brave American armies arrived in extremis to liberate them. And all the (American) flag-waving our good citizens were doing on those ritual “Remembrance Days” looked all of a sudden like a ritual cover-up for their own unacknowledged mistakes, misjudgments and omissions.

—Pierre Joris

.

Pierre Joris—2011 saw the publication of Pierre Joris: Cartographies of the In-between, edited by Peter Cockelbergh, with essays on Joris’ work by, among others, Mohamed Bennis, Charles Bernstein, Nicole Brossard, Clayton Eshleman, Allen Fisher, Christine Hume, Robert Kelly, Abdelwahab Meddeb, Jennifer Moxley, Jean Portante, Carrie Noland, Alice Notley, Marjorie Perloff & Nicole Peyrafitte (Litteraria Pragensia, Charles University, Prague, 2011). Pierre Joris, while raised in Luxembourg, has moved between Europe, the US & North Africa for half a century years, publishing close 50 books of poetry, essays, translations and anthologies. In 2014 he published Barzakh — Poems 2000-2012 (Black Widow Press), Breathturn into Timestead: The Collected Later Poems of Paul Celan (Farrar, Straus & Giroux), A Voice full of Cities: The Collected Essays of Robert Kelly (co-edited with Peter Cockelbergh, Contra Mundum Press) and Bernat Manciet’s Ode to James Dean (co-translated from Occitan with Nicole Peyrafitte; mindmade books). 2013 had brought Meditations on the Stations of Mansur al-Hallaj (poems) from Chax Press & The University of California Book of North African Literature (vol. 4 in the Poems for the Millennium series), coedited with Habib Tengour (UCP).

Other recent books include Exile is My Trade: A Habib Tengour Reader edited, introduced & translated by Pierre Joris (Black Widow Press, 2012); The Meridian: Final Version—Drafts—Materials by Paul Celan (Stanford U.P. 2011) which received the 2012 MLA Aldo and Jeanne Scaglione Prize for a Translation of a Literary Work; Justifying the Margins: Essays 1990-2006 (Salt Books); Aljibar I & II (Poems, Editions PHI). Further translations include Paul Celan: Selections (UC Press) & Lightduress by Paul Celan which received the 2005 PEN Poetry Translation Award. With Jerome Rothenberg he edited Poems for the Millennium, vol. 1 & 2: The University of California Books of Modern & Postmodern Poetry.

Pierre Joris lives in Bay Ridge, Brooklyn with his wife, performance artist Nicole Peyrafitte. Check out his website & Nomadics Blog.

.