o

o

Capo di tutti capi

o

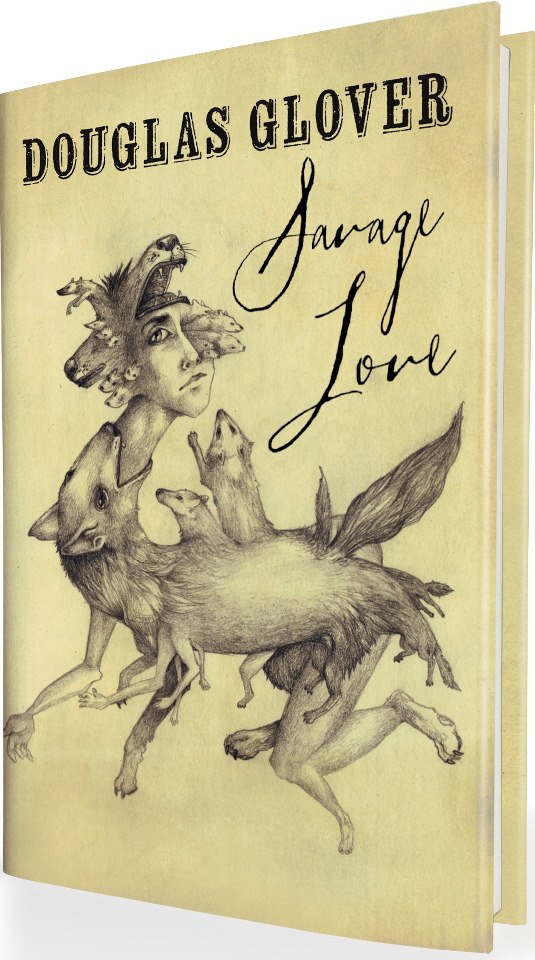

Douglas Glover’s obscurity is legendary; he is mostly known for being unknown. He has been called “the most eminent unknown Canadian writer alive” (Maclean’s Magazine, The National Post). But for sheer over-the-top hyperbole, nothing beats the opening of a recent piece about him in Quill and Quire in Toronto, which elevates his lack of celebrity to the epic: “Certain mysteries abide in this world: the Gordian Knot, the Holy Trinity, and the literary obscurity of Douglas Glover.” Luckily, he owns a dog and is not completely alone in the world. And occasionally someone actually reads what he writes: He has also been called “a master of narrative structure” (Wall Street Journal) and “the mad genius of Can Lit” (Globe and Mail) whose stories are “as radiant and stirring as anything available in contemporary literature” (Los Angeles Review of Books) and whose work “demands comparison to [Cormac] McCarthy, Barry Hannah, Donald Barthelme, William Faulkner” (Music & Literature). A new story collection, Savage Love, was published in 2013.

Douglas Glover’s obscurity is legendary; he is mostly known for being unknown. He has been called “the most eminent unknown Canadian writer alive” (Maclean’s Magazine, The National Post). But for sheer over-the-top hyperbole, nothing beats the opening of a recent piece about him in Quill and Quire in Toronto, which elevates his lack of celebrity to the epic: “Certain mysteries abide in this world: the Gordian Knot, the Holy Trinity, and the literary obscurity of Douglas Glover.” Luckily, he owns a dog and is not completely alone in the world. And occasionally someone actually reads what he writes: He has also been called “a master of narrative structure” (Wall Street Journal) and “the mad genius of Can Lit” (Globe and Mail) whose stories are “as radiant and stirring as anything available in contemporary literature” (Los Angeles Review of Books) and whose work “demands comparison to [Cormac] McCarthy, Barry Hannah, Donald Barthelme, William Faulkner” (Music & Literature). A new story collection, Savage Love, was published in 2013.

Glover is the author of five story collections, four novels, three books of essays, Notes Home from a Prodigal Son, Attack of the Copula Spiders, and The Erotics of Restraint, and The Enamoured Knight, a book about Don Quixote and novel form. His novel Elle won the 2003 Governor-General’s Award for Fiction, was a finalist for the IMPAC Dublin Literary Award, and was optioned by Isuma Igloolik Productions, makers of Atanarjuat, The Fast Runner. His story book A Guide to Animal Behaviour was a finalist for the 1991 Governor-General’s Award. His stories have been frequently anthologized, notably in The Best American Short Stories, Best Canadian Stories, and The New Oxford Book of Canadian Stories. He was the subject of a TV documentary in a series called The Writing Life and a collection of critical essays, The Art of Desire, The Fiction of Douglas Glover, edited by Bruce Stone.

Glover has taught at several institutions of high learning but mostly wishes he hadn’t. For two years he produced and hosted The Book Show, a weekly half-hour literary interview program which originated at WAMC in Albany and was syndicated on various public radio stations and around the world on Voice of America. He edited the annual Best Canadian Stories from 1996 to 2006. He has two sons, Jacob and Jonah, who will doubtless turn out better than he did.

See also “Making Friends with a Stranger: Albert Camus’s L’Étranger,” an essay in CNQ:Canadian Notes & Queries; “Consciousness & Masturbation: A Note on Witold Gombrowicz’s Onanomaniacal Novel Cosmos,” an essay in 3:AM Magazine; “Pedro the Uncanny: A Note on Juan Rulfo’s Pedro Páramo,” an essay in Biblioasis International Translation Series Online; “A Scrupulous Fidelity: Thomas Bernhard’s The Loser,” an essay in The Brooklyn Rail; “Mappa Mundi: The Structure of Western Thought,” an essay on the history of ideas also in The Brooklyn Rail; and a dozen extremely wise epigrams at Global Brief.

Senior Editors

o

Book Reviews

Jason DeYoung lives in Atlanta, Georgia. His work has recently appeared in Corium, The Los Angeles Review, The Fiddleback, New Orleans Review, and Numéro Cinq.

Jason DeYoung lives in Atlanta, Georgia. His work has recently appeared in Corium, The Los Angeles Review, The Fiddleback, New Orleans Review, and Numéro Cinq.

Contact: jasondeyoung@old.numerocinqmagazine.com.

.

.

.

.

Numéro Cinq at the Movies

R. W. Gray (Numéro Cinq at the Movies) was born and raised on the northwest coast of British Columbia, and received a PhD in Poetry and Psychoanalysis from the University of Alberta in 2003. His most recent book, a short story collection entitled Entropic, won the $25,000 Thomas Raddall Fiction Award in 2016. Additionally, he is the author of Crisp, a short story collection, and two serialized novels in Xtra West magazine and has published poetry in various journals and anthologies, including Arc, Grain, Event, and dANDelion. He also has had ten short screenplays produced, including Alice & Huck and Blink. He currently teaches Film at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton..

R. W. Gray (Numéro Cinq at the Movies) was born and raised on the northwest coast of British Columbia, and received a PhD in Poetry and Psychoanalysis from the University of Alberta in 2003. His most recent book, a short story collection entitled Entropic, won the $25,000 Thomas Raddall Fiction Award in 2016. Additionally, he is the author of Crisp, a short story collection, and two serialized novels in Xtra West magazine and has published poetry in various journals and anthologies, including Arc, Grain, Event, and dANDelion. He also has had ten short screenplays produced, including Alice & Huck and Blink. He currently teaches Film at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton..

.

Editor-at-Large

Fernando Sdrigotti is a writer, cultural critic, and recovering musician. He was born in Rosario, Argentina, and now lives and works in London. He is the author of Dysfunctional Males, a story collection, and Shetlag: una novela acentuada. He is a contributing editor at 3am Magazine and the editor-in-chief of Minor Literature[s]. He tweets at @f_sd.

Fernando Sdrigotti is a writer, cultural critic, and recovering musician. He was born in Rosario, Argentina, and now lives and works in London. He is the author of Dysfunctional Males, a story collection, and Shetlag: una novela acentuada. He is a contributing editor at 3am Magazine and the editor-in-chief of Minor Literature[s]. He tweets at @f_sd.

.

Translations

Benjamin Woodard lives in Connecticut. His recent fiction has appeared in Cheap Pop, decomP magazinE, Spartan, and Numéro Cinq. His reviews and essays have been featured in, or are forthcoming from, Numéro Cinq, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Rain Taxi Review of Books, The Kenyon Review, and other fine publications. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle. You can find him at benjaminjwoodard.com.

Benjamin Woodard lives in Connecticut. His recent fiction has appeared in Cheap Pop, decomP magazinE, Spartan, and Numéro Cinq. His reviews and essays have been featured in, or are forthcoming from, Numéro Cinq, Vol. 1 Brooklyn, Rain Taxi Review of Books, The Kenyon Review, and other fine publications. He is a member of the National Book Critics Circle. You can find him at benjaminjwoodard.com.

Contact bwoodard@old.numerocinqmagazine.com.

.

Poetry Editors

Susan Aizenberg is the author of three poetry collections: Quiet City (BkMk Press 2015); Muse (Crab Orchard Poetry Series 2002); and Peru in Take Three: 2/AGNI New Poets Series (Graywolf Press 1997) and co-editor with Erin Belieu of The Extraordinary Tide: New Poetry by American Women (Columbia University Press 2001). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in many journals, among them The North American Review, Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry, Prairie Schooner, Blackbird, Connotation Press, Spillway, The Journal, Midwest Quarterly Review, Hunger Mountain, Alaska Quarterly Review, and the Philadelphia Inquirer and have been reprinted and are forthcoming in several anthologies, including Ley Lines (Wilfrid Laurier UP) and Wild and Whirling Words: A Poetic Conversation (Etruscan). Her awards include a Crab Orchard Poetry Series Award, the Nebraska Book Award for Poetry and Virginia Commonwealth University’s Levis Prize for Muse, a Distinguished Artist Fellowship from the Nebraska Arts Council, the Mari Sandoz Award from the Nebraska Library Association, and a Glenna Luschei Prairie Schooner award. She can be reached through her website, susanaizenberg.com..

Susan Aizenberg is the author of three poetry collections: Quiet City (BkMk Press 2015); Muse (Crab Orchard Poetry Series 2002); and Peru in Take Three: 2/AGNI New Poets Series (Graywolf Press 1997) and co-editor with Erin Belieu of The Extraordinary Tide: New Poetry by American Women (Columbia University Press 2001). Her poems have appeared or are forthcoming in many journals, among them The North American Review, Ted Kooser’s American Life in Poetry, Prairie Schooner, Blackbird, Connotation Press, Spillway, The Journal, Midwest Quarterly Review, Hunger Mountain, Alaska Quarterly Review, and the Philadelphia Inquirer and have been reprinted and are forthcoming in several anthologies, including Ley Lines (Wilfrid Laurier UP) and Wild and Whirling Words: A Poetic Conversation (Etruscan). Her awards include a Crab Orchard Poetry Series Award, the Nebraska Book Award for Poetry and Virginia Commonwealth University’s Levis Prize for Muse, a Distinguished Artist Fellowship from the Nebraska Arts Council, the Mari Sandoz Award from the Nebraska Library Association, and a Glenna Luschei Prairie Schooner award. She can be reached through her website, susanaizenberg.com..

Susan Gillis has published three books of poetry, most recently The Rapids (Brick Books, 2012), and several chapbooks, including The Sky These Days (Thee Hellbox Press, 2015) and Twenty Views of the Lachine Rapids (Gaspereau Press, 2012). Volta (Signature Editions, 2002) won the A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry. She is a member of the collaborative poetry group Yoko’s Dogs, whose work appears regularly in print and online, and is collected in Rhinoceros (Gaspereau Press, 2016) and Whisk (Pedlar Press, 2013). Susan divides her time between Montreal and rural Ontario..

Susan Gillis has published three books of poetry, most recently The Rapids (Brick Books, 2012), and several chapbooks, including The Sky These Days (Thee Hellbox Press, 2015) and Twenty Views of the Lachine Rapids (Gaspereau Press, 2012). Volta (Signature Editions, 2002) won the A.M. Klein Prize for Poetry. She is a member of the collaborative poetry group Yoko’s Dogs, whose work appears regularly in print and online, and is collected in Rhinoceros (Gaspereau Press, 2016) and Whisk (Pedlar Press, 2013). Susan divides her time between Montreal and rural Ontario..

.

Managing Editor.

Deirdre Baker is a freelance web and copy editor living in Toronto. She worked for nearly three decades at the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, most recently as manager of the Legislature’s website and intranet. After years of bills, proceedings, debates, policies, and procedures, she is delighted to finally have something interesting to read for work.

Deirdre Baker is a freelance web and copy editor living in Toronto. She worked for nearly three decades at the Legislative Assembly of Ontario, most recently as manager of the Legislature’s website and intranet. After years of bills, proceedings, debates, policies, and procedures, she is delighted to finally have something interesting to read for work.

.

.

Chief Technical Officer/Internet Security

Jonah Glover is a twenty-three-year-old human male. Jonah was hired into a technical role despite a long history of shoving chalk into the Glover family VCR. His tenure as CTO is a brazen act of nepotism by DG, so he says. In truth, he has rescued the magazine from malware attacks and hosting issues over and over again. He also designed the logo (many years ago). He works as a software engineer in Seattle and is completing a degree at the University of Waterloo.

Jonah Glover is a twenty-three-year-old human male. Jonah was hired into a technical role despite a long history of shoving chalk into the Glover family VCR. His tenure as CTO is a brazen act of nepotism by DG, so he says. In truth, he has rescued the magazine from malware attacks and hosting issues over and over again. He also designed the logo (many years ago). He works as a software engineer in Seattle and is completing a degree at the University of Waterloo.

.

.

..

Contributing Editors.

..

The author of nine novels, three collections of short fiction, two books of essays and five books of poetry, Rikki Ducornet has received both a Lannan Literary Fellowship and the Lannan Literary Award For Fiction. She has received the Bard College Arts and Letters award and, in 2008, an Academy Award in Literature. Her work is widely published abroad. Recent exhibitions of her paintings include the solo show Desirous at the Pierre Menard Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 2007, and the group shows: O Reverso Do Olhar in Coimbra, Portugal, in 2008, and El Umbral Secreto at the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende in Santiago, Chile, in 2009. She has illustrated books by Jorge Luis Borges, Robert Coover, Forest Gander, Kate Bernheimer, Joanna Howard and Anne Waldman among others. Her collected papers including prints and drawings are in the permanent collection of the Ohio State University Rare Books and Manuscripts Library. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, Santiago Chile, The McMaster University Museum, Ontario, Canada, and The Biblioteque Nationale, Paris.

The author of nine novels, three collections of short fiction, two books of essays and five books of poetry, Rikki Ducornet has received both a Lannan Literary Fellowship and the Lannan Literary Award For Fiction. She has received the Bard College Arts and Letters award and, in 2008, an Academy Award in Literature. Her work is widely published abroad. Recent exhibitions of her paintings include the solo show Desirous at the Pierre Menard Gallery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 2007, and the group shows: O Reverso Do Olhar in Coimbra, Portugal, in 2008, and El Umbral Secreto at the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende in Santiago, Chile, in 2009. She has illustrated books by Jorge Luis Borges, Robert Coover, Forest Gander, Kate Bernheimer, Joanna Howard and Anne Waldman among others. Her collected papers including prints and drawings are in the permanent collection of the Ohio State University Rare Books and Manuscripts Library. Her work is in the permanent collections of the Museo de la Solidaridad Salvador Allende, Santiago Chile, The McMaster University Museum, Ontario, Canada, and The Biblioteque Nationale, Paris.

.

Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves (1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).

Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves (1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).

Julie Larios is the author of four books for children: On the Stairs (1995), Have You Ever Done That? (named one of Smithsonian Magazine’s Outstanding Children’s Books 2001), Yellow Elephant (a Book Sense Pick and Boston Globe–Horn Book Honor Book, 2006) and Imaginary Menagerie: A Book of Curious Creatures (shortlisted for the Cybil Award in Poetry, 2008). For five years she was the Poetry Editor for The Cortland Review, and her poetry for adults has been published by The Atlantic Monthly, McSweeney’s, Swink, The Georgia Review, Ploughshares, The Threepenny Review, Field, and others. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize, a Pushcart Prize for Poetry, and a Washington State Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowship. Her work has been chosen for The Best American Poetry series by Billy Collins (2006) and Heather McHugh (2007) and was performed as part of the Vox series at the New York City Opera (2010). Recently she collaborated with the composer Dag Gabrielson and other New York musicians, filmmakers and dancers on a cross-discipline project titled 1,2,3. It was selected for showing at the American Dance Festival (International Screendance Festival) and had its premiere at Duke University on July 13th, 2013.

Julie Larios is the author of four books for children: On the Stairs (1995), Have You Ever Done That? (named one of Smithsonian Magazine’s Outstanding Children’s Books 2001), Yellow Elephant (a Book Sense Pick and Boston Globe–Horn Book Honor Book, 2006) and Imaginary Menagerie: A Book of Curious Creatures (shortlisted for the Cybil Award in Poetry, 2008). For five years she was the Poetry Editor for The Cortland Review, and her poetry for adults has been published by The Atlantic Monthly, McSweeney’s, Swink, The Georgia Review, Ploughshares, The Threepenny Review, Field, and others. She is the recipient of an Academy of American Poets Prize, a Pushcart Prize for Poetry, and a Washington State Arts Commission/Artist Trust Fellowship. Her work has been chosen for The Best American Poetry series by Billy Collins (2006) and Heather McHugh (2007) and was performed as part of the Vox series at the New York City Opera (2010). Recently she collaborated with the composer Dag Gabrielson and other New York musicians, filmmakers and dancers on a cross-discipline project titled 1,2,3. It was selected for showing at the American Dance Festival (International Screendance Festival) and had its premiere at Duke University on July 13th, 2013.

Sydney Lea is the former Poet Laureate of Vermont (2011-2015). He founded New England Review in 1977 and edited it till 1989. His poetry collection Pursuit of a Wound (University of Illinois Press, 2000) was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. Another collection, To the Bone: New and Selected Poems, was co-winner of the 1998 Poets’ Prize. In 1989, Lea also published the novel A Place in Mind with Scribner. Lea has received fellowships from the Rockefeller, Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, and has taught at Dartmouth, Yale, Wesleyan, Vermont College of Fine Arts and Middlebury College, as well as at Franklin College in Switzerland and the National Hungarian University in Budapest. His stories, poems, essays and criticism have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New Republic, The New York Times, Sports Illustrated and many other periodicals, as well as in more than forty anthologies. His selection of literary essays, A Hundred Himalayas, was published by the University of Michigan Press in 2012, and Skyhorse Publications released A North Country Life: Tales of Woodsmen, Waters and Wildlife in 2013. In 2015 he published a non-fiction collection, What’s the Story? Reflections on a Life Grown Long (many of the essays appeared first on Numéro Cinq). His twelfth poetry collection, No Doubt the Nameless, was published this spring by Four Way Books.

Sydney Lea is the former Poet Laureate of Vermont (2011-2015). He founded New England Review in 1977 and edited it till 1989. His poetry collection Pursuit of a Wound (University of Illinois Press, 2000) was one of three finalists for the Pulitzer Prize for poetry. Another collection, To the Bone: New and Selected Poems, was co-winner of the 1998 Poets’ Prize. In 1989, Lea also published the novel A Place in Mind with Scribner. Lea has received fellowships from the Rockefeller, Fulbright and Guggenheim Foundations, and has taught at Dartmouth, Yale, Wesleyan, Vermont College of Fine Arts and Middlebury College, as well as at Franklin College in Switzerland and the National Hungarian University in Budapest. His stories, poems, essays and criticism have appeared in The New Yorker, The Atlantic, The New Republic, The New York Times, Sports Illustrated and many other periodicals, as well as in more than forty anthologies. His selection of literary essays, A Hundred Himalayas, was published by the University of Michigan Press in 2012, and Skyhorse Publications released A North Country Life: Tales of Woodsmen, Waters and Wildlife in 2013. In 2015 he published a non-fiction collection, What’s the Story? Reflections on a Life Grown Long (many of the essays appeared first on Numéro Cinq). His twelfth poetry collection, No Doubt the Nameless, was published this spring by Four Way Books.

.

Special Correspondents

##

Victoria Best taught at St John’s College, Cambridge for 13 years. Her books include: Critical Subjectivities; Identity and Narrative in the work of Colette and Marguerite Duras (2000), An Introduction to Twentieth Century French Literature (2002) and, with Martin Crowley, The New Pornographies; Explicit Sex in Recent French Fiction and Film (2007). A freelance writer since 2012, she has published essays in Cerise Press and Open Letters Monthly and is currently writing a book on crisis and creativity. She is also co-editor of the quarterly review magazine Shiny New Books (http://shinynewbooks.co.uk).

Victoria Best taught at St John’s College, Cambridge for 13 years. Her books include: Critical Subjectivities; Identity and Narrative in the work of Colette and Marguerite Duras (2000), An Introduction to Twentieth Century French Literature (2002) and, with Martin Crowley, The New Pornographies; Explicit Sex in Recent French Fiction and Film (2007). A freelance writer since 2012, she has published essays in Cerise Press and Open Letters Monthly and is currently writing a book on crisis and creativity. She is also co-editor of the quarterly review magazine Shiny New Books (http://shinynewbooks.co.uk).

.

Jeff Bursey is a literary critic and author of the picaresque novel Mirrors on which dust has fallen (Verbivoracious Press, 2015) and the political satire Verbatim: A Novel (Enfield & Wizenty, 2010), both of which take place in the same fictional Canadian province. His forthcoming book, Centring the Margins: Essays and Reviews (Zero Books, July 2016), is a collection of literary criticism that appeared in American Book Review, Books in Canada, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, The Quarterly Conversation, and The Winnipeg Review, among other places. He’s a Contributing Editor at The Winnipeg Review, an Associate Editor at Lee Thompson’s Galleon, and a Special Correspondent for Numéro Cinq. He makes his home on Prince Edward Island in Canada’s Far East.

Jeff Bursey is a literary critic and author of the picaresque novel Mirrors on which dust has fallen (Verbivoracious Press, 2015) and the political satire Verbatim: A Novel (Enfield & Wizenty, 2010), both of which take place in the same fictional Canadian province. His forthcoming book, Centring the Margins: Essays and Reviews (Zero Books, July 2016), is a collection of literary criticism that appeared in American Book Review, Books in Canada, The Review of Contemporary Fiction, The Quarterly Conversation, and The Winnipeg Review, among other places. He’s a Contributing Editor at The Winnipeg Review, an Associate Editor at Lee Thompson’s Galleon, and a Special Correspondent for Numéro Cinq. He makes his home on Prince Edward Island in Canada’s Far East.

Gary Garvin lives in Portland, Oregon, where he writes and reflects on a thirty-year career teaching English. His short stories and essays have appeared in TriQuarterly, Web Conjunctions, Fourth Genre, Numéro Cinq, the minnesota review, New Novel Review, Confrontation, The New Review, The Santa Clara Review, The South Carolina Review, The Berkeley Graduate, and The Crescent Review. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and a novel. His architectural models can be found at Under Construction. A catalog of his writing can be found at Fictions.

Gary Garvin lives in Portland, Oregon, where he writes and reflects on a thirty-year career teaching English. His short stories and essays have appeared in TriQuarterly, Web Conjunctions, Fourth Genre, Numéro Cinq, the minnesota review, New Novel Review, Confrontation, The New Review, The Santa Clara Review, The South Carolina Review, The Berkeley Graduate, and The Crescent Review. He is currently at work on a collection of essays and a novel. His architectural models can be found at Under Construction. A catalog of his writing can be found at Fictions.

Genese Grill is an artist, translator, writer, and cultural conspirator living in Burlington, Vermont. She is the author of The World as Metaphor in Robert Musil’s ‘The Man without Qualities’ (Camden House, 2012) and the translator of a collection of Robert Musil’s short prose, Thought Flights (Contra Mundum, 2015). She is currently working on completing a collection of essays exploring the tension between spirit and matter in contemporary culture and a room-sized, illuminated, accordion book inscribed with one of the essays from the collection, along with many other fanatical projects. You can find Genese online at genesegrill.blogspot.com.

.

Jason Lucarelli is a graduate of the MFA in Creative Writing program at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. His work has appeared in Numéro Cinq, The Literarian, 3:AM Magazine, Litro, Squawk Back, and NANO Fiction.

Jason Lucarelli is a graduate of the MFA in Creative Writing program at the Vermont College of Fine Arts. His work has appeared in Numéro Cinq, The Literarian, 3:AM Magazine, Litro, Squawk Back, and NANO Fiction.

..

.

.

Bruce Stone is a Wisconsin native and graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts (MFA, 2002). In 2004, he edited a great little book of essays on Douglas Glover’s fiction, The Art of Desire (Oberon Press). His own essays have appeared in Miranda, Nabokov Studies, Review of Contemporary Fiction, Los Angeles Review of Books, F. Scott Fitzgerald Review and Salon. His fiction has appeared most recently in Straylight and Numéro Cinq. He currently teaches writing at UCLA.

.

.

Julie Trimingham was born in Montreal and raised semi-nomadically. She trained as a painter at Yale University and as a director at the Canadian Film Centre in Toronto. Her film work has screened at festivals and been broadcast internationally, and has won or been nominated for a number of awards. Julie taught screenwriting at the Vancouver Film School for several years; she has since focused exclusively on writing fiction. Her online journal, Notes from Elsewhere, features reportage from places real and imagined. Her first novel, Mockingbird, was published in 2013.

.

.

.

Production Editors

.

Alyssa Colton has a PhD in English with creative dissertation from the University at Albany, State University of New York. Her fiction has been published in The Amaranth Review and Women Writers. Her essays have appeared in Literary Arts Review, Author Magazine, Mothering, Moxie: For Women Who Dare, Iris: A Journal about Women, and on WAMC: Northeast Public Radio. Alyssa has taught classes in writing, literature, and theater at the University at Albany, the College of St. Rose, and Berkshire Community College and blogs about writing at abcwritingediting.

Alyssa Colton has a PhD in English with creative dissertation from the University at Albany, State University of New York. Her fiction has been published in The Amaranth Review and Women Writers. Her essays have appeared in Literary Arts Review, Author Magazine, Mothering, Moxie: For Women Who Dare, Iris: A Journal about Women, and on WAMC: Northeast Public Radio. Alyssa has taught classes in writing, literature, and theater at the University at Albany, the College of St. Rose, and Berkshire Community College and blogs about writing at abcwritingediting.

.

Nowick Gray writes fiction, essays and creative nonfiction that likes to bend boundaries and confound categories. He also works as a freelance copy editor and enjoys playing African drums. Having survived American suburbs, the Quebec Arctic and the BC wilderness, Nowick is now based in Victoria, frequenting tropical locations in winter months..

Nowick Gray writes fiction, essays and creative nonfiction that likes to bend boundaries and confound categories. He also works as a freelance copy editor and enjoys playing African drums. Having survived American suburbs, the Quebec Arctic and the BC wilderness, Nowick is now based in Victoria, frequenting tropical locations in winter months..

.

Nic Leigh has had work published in Juked, The Collagist, UNSAID, Atticus Review, Requited, Gobbet, and DIAGRAM. A chapbook, Confidences, won the Cobalt/Thumbnail Flash Fiction contest and is forthcoming from Cobalt Press. Leigh is also a fiction reader for Guernica.

Nic Leigh has had work published in Juked, The Collagist, UNSAID, Atticus Review, Requited, Gobbet, and DIAGRAM. A chapbook, Confidences, won the Cobalt/Thumbnail Flash Fiction contest and is forthcoming from Cobalt Press. Leigh is also a fiction reader for Guernica.

.

.

Kathryn Para is an award-winning, multi-genre writer with a MFA in Creative Writing from UBC. Her fiction, non-fiction and poetry have been published in Grain, Room of One’s Own, Geist, Sunstream, and Vancouver Review. She is the 2013 Winner of Mother Tongue Publishing’s Search for the Great BC Novel Contest with, Lucky, her first novel, which was also shortlisted for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize in 2014. Her stage play, Honey, debuted in 2004. She has also written, directed and produced short films.

Kathryn Para is an award-winning, multi-genre writer with a MFA in Creative Writing from UBC. Her fiction, non-fiction and poetry have been published in Grain, Room of One’s Own, Geist, Sunstream, and Vancouver Review. She is the 2013 Winner of Mother Tongue Publishing’s Search for the Great BC Novel Contest with, Lucky, her first novel, which was also shortlisted for the Ethel Wilson Fiction Prize in 2014. Her stage play, Honey, debuted in 2004. She has also written, directed and produced short films.

Daniel Davis Wood is a writer based in Birmingham, England. His debut novel, Blood and Bone, won the 2014 Viva La Novella Prize in his native Australia. He is also the author of Frontier Justice, a study of the influence of the nineteenth century frontier on American literature, and the editor of a collection of essays on the African American writer Edward P. Jones. He can be found online at www.danieldaviswood.com..

Daniel Davis Wood is a writer based in Birmingham, England. His debut novel, Blood and Bone, won the 2014 Viva La Novella Prize in his native Australia. He is also the author of Frontier Justice, a study of the influence of the nineteenth century frontier on American literature, and the editor of a collection of essays on the African American writer Edward P. Jones. He can be found online at www.danieldaviswood.com..

.

.

Assistant to the Editor

.

Mary Brindley is a Vermont-born copywriter living in Boston. A recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts, she writes creative nonfiction, performs improv, and is about to move to London.

Mary Brindley is a Vermont-born copywriter living in Boston. A recent graduate of the Vermont College of Fine Arts, she writes creative nonfiction, performs improv, and is about to move to London.

..

.

m

Contributors

.

A. Anupama is a U.S.-born, Indian-American poet and translator whose work has appeared in several literary publications, including The Bitter Oleander, Monkeybicycle, The Alembic, Numéro Cinq and decomP magazinE. She received her MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2012. She currently lives and writes in the Hudson River valley of New York, where she blogs about poetic inspiration at seranam.com.

A. Anupama is a U.S.-born, Indian-American poet and translator whose work has appeared in several literary publications, including The Bitter Oleander, Monkeybicycle, The Alembic, Numéro Cinq and decomP magazinE. She received her MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2012. She currently lives and writes in the Hudson River valley of New York, where she blogs about poetic inspiration at seranam.com.

.

Currently based in Mexico City, Dylan Brennan writes poetry, essays and memoirs. His debut collection, Blood Oranges, for which he won The Patrick Kavanagh Award runner-up prize, was published by The Dreadful Press in 2014. His co-edited volume of academic essays Rethinking Juan Rulfo’s Creative World: Prose, Photography, Film is available now from Legenda Books (2016). In addition to his work as Mexico Curator for Numéro Cinq, he regularly contributes to the online Mexican literary site Portal de Letras. Twitter: @DylanJBrennan.

Currently based in Mexico City, Dylan Brennan writes poetry, essays and memoirs. His debut collection, Blood Oranges, for which he won The Patrick Kavanagh Award runner-up prize, was published by The Dreadful Press in 2014. His co-edited volume of academic essays Rethinking Juan Rulfo’s Creative World: Prose, Photography, Film is available now from Legenda Books (2016). In addition to his work as Mexico Curator for Numéro Cinq, he regularly contributes to the online Mexican literary site Portal de Letras. Twitter: @DylanJBrennan.

Jeremy Brunger, originally from Tennessee, is a writer attending a graduate program at the University of Chicago. His interests trend toward the Marxian: how capital transforms us, abuses us, mocks us. His writing on philosophy and politics has been featured on Truthout, The Hampton Institute, and 3 AM Magazine and his poetry has appeared in the Chiron Review and Sibling Rivalry Press. He can be contacted at jbrunger@uchicago.edu.

Jeremy Brunger, originally from Tennessee, is a writer attending a graduate program at the University of Chicago. His interests trend toward the Marxian: how capital transforms us, abuses us, mocks us. His writing on philosophy and politics has been featured on Truthout, The Hampton Institute, and 3 AM Magazine and his poetry has appeared in the Chiron Review and Sibling Rivalry Press. He can be contacted at jbrunger@uchicago.edu.

.

.

..

Michael Carson lives on the Gulf Coast. His non-fiction has appeared at The Daily Beast and Salon, and his fiction in the short story anthology, The Road Ahead: Stories of the Forever War. He helps edit the Wrath-Bearing Tree and is currently working towards an MFA in Fiction at the Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Michael Carson lives on the Gulf Coast. His non-fiction has appeared at The Daily Beast and Salon, and his fiction in the short story anthology, The Road Ahead: Stories of the Forever War. He helps edit the Wrath-Bearing Tree and is currently working towards an MFA in Fiction at the Vermont College of Fine Arts.

.

.

Laura Michele Diener teaches medieval history and women’s studies at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. She received her PhD in history from The Ohio State University and has studied at Vassar College, Newnham College, Cambridge, and most recently, Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her creative writing has appeared in The Catholic Worker, Lake Effect, Appalachian Heritage,and Cargo Literary Magazine, and she is a regular contributor to Yes! Magazine..

Laura Michele Diener teaches medieval history and women’s studies at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. She received her PhD in history from The Ohio State University and has studied at Vassar College, Newnham College, Cambridge, and most recently, Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her creative writing has appeared in The Catholic Worker, Lake Effect, Appalachian Heritage,and Cargo Literary Magazine, and she is a regular contributor to Yes! Magazine..

.

Daniel Green is a writer and literary critic whose essays, reviews, and stories have appeared in a variety of publications. He is the author of Beyond the Blurb: On Critics and Criticism (2016).

.

.

.

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet Mary Kathryn Jablonski is now an administrative director in holistic healthcare. She is author of the chapbook To the Husband I Have Not Yet Met, and her poems have appeared in numerous literary journals including the Beloit Poetry Journal, Blueline, Home Planet News, Salmagundi, and Slipstream, among others. Her artwork has been widely exhibited throughout the Northeast and is held in private and public collections.

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet Mary Kathryn Jablonski is now an administrative director in holistic healthcare. She is author of the chapbook To the Husband I Have Not Yet Met, and her poems have appeared in numerous literary journals including the Beloit Poetry Journal, Blueline, Home Planet News, Salmagundi, and Slipstream, among others. Her artwork has been widely exhibited throughout the Northeast and is held in private and public collections.

.

Carolyn Ogburn lives in the mountains of Western North Carolina where she takes on a variety of worldly topics from the quiet comfort of her porch. Her writing can be found in the Asheville Poetry Review, the Potomac Review, the Indiana Review, and more. A graduate of Oberlin Conservatory and NC School of the Arts, she writes on literature, autism, music, and disability rights. She is completing an MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and is at work on her first novel.

Carolyn Ogburn lives in the mountains of Western North Carolina where she takes on a variety of worldly topics from the quiet comfort of her porch. Her writing can be found in the Asheville Poetry Review, the Potomac Review, the Indiana Review, and more. A graduate of Oberlin Conservatory and NC School of the Arts, she writes on literature, autism, music, and disability rights. She is completing an MFA at Vermont College of Fine Arts, and is at work on her first novel.

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

.

Frank Richardson lives in Houston where he teaches English and Humanities. He received his MFA in Fiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts.

Frank Richardson lives in Houston where he teaches English and Humanities. He received his MFA in Fiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts.

.

././

…

.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Natalia Sarkissian has an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She was an editor and a contributor at Numéro Cinq from 2010-2017.

Natalia Sarkissian has an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She was an editor and a contributor at Numéro Cinq from 2010-2017.

.

Joseph Schreiber is a writer and photographer living in Calgary. He maintains a book blog called Rough Ghosts. His writing has also been published at 3:AM, Minor Literature[s] and The Scofield. He tweets @roughghosts.

Joseph Schreiber is a writer and photographer living in Calgary. He maintains a book blog called Rough Ghosts. His writing has also been published at 3:AM, Minor Literature[s] and The Scofield. He tweets @roughghosts.

.

.

.

Dorian Stuber teaches at Hendrix College. He has written for Open Letters Monthly, The Scofield, and Words without Borders. He blogs about books at www.eigermonchjungfrau.wordpress.com.

Dorian Stuber teaches at Hendrix College. He has written for Open Letters Monthly, The Scofield, and Words without Borders. He blogs about books at www.eigermonchjungfrau.wordpress.com.

.

.

.

.

Authors & Artists of Numéro Cinq

.

Ryem Abrahamson • Abdallah Ben Salem d’Aix • Alejandro de Acosta • Caroline Adderson • José Eduardo Agualusa • Susan Aizenberg • Ramón Alejandro • Taiaike Alfred • Gini Alhadeff • Abigail Allen • Steve Almond • Darran Anderson • Trevor Anderson • Jorge Carrera Andrade • Ralph Angel • A. Anupama • Guillaume Apollinaire • Jamaluddin Aram • Fernando Aramburu • Louis Armand • Melissa Armstrong • Tammy Armstrong • Glenn Arnold • Miguel Arteta • Adam Arvidson • Nick Arvin • Kim Aubrey • Shushan Avagyan • Steven Axelrod • Elizabeth Babyn • J. Karl Bogartte • Louise Bak • Bonnie Baker • Sybil Baker • Martin Balgach • Brandon Ballengée • Zsófia Bán • Phyllis Barber • John Banville • Byrna Barclay • Mike Barnes • Stuart Barnes • Kevin Barry • Donald Bartlett • Todd Bartol • John Barton • Sierra Bates • Svetislav Basarav • Charles Baudelaire • Tom Bauer • Melissa Considine Beck • Joshua Beckman • Laura Behr • Gerard Beirne • Amanda Bell • Ian Bell • Madison Smartt Bell • Dodie Bellamy • Joe David Bellamy • Leonard Bellanca • Russell Bennetts • Brianna Berbenuik • Samantha Bernstein • Michelle Berry • Jen Bervin • Victoria Best • Darren Bifford • Nathalie Bikoro • Eula Biss • Susan Sanford Blades • François Blais • Clark Blaise • Denise Blake • Vanessa Blakeslee • Rimas Blekaitis • Liz Blood • Harold Bloom • Ronna Bloom • Michelle Boisseau • Stephanie Bolster • John Bolton • Jody Bolz • Danila Botha • Danny Boyd • Donald Breckenridge • Dylan Brennan • Mary Brindley • Stephen Brockbank • Fleda Brown • Laura Catherine Brown • Nickole Brown • Lynne M. Browne • Julie Bruck • Jeremy Brunger • Michael Bryson • John Bullock • Bunkong Tuon • Diane Burko • Jeff Bursey • Peter Bush • Jane Buyers • Jowita Bydlowska • Mary Byrne • Agustín Cadena • David Caleb • Chris Campanioni • Jane Campion • J. N. F. M. à Campo • Jared Carney • David Carpenter • Michael Carson • Mircea Cărtărescu • Ricardo Cázares • Daniela Cascella • Blanca Castellón • Michael Catherwood • Anton Chekhov • David Celone • Corina Martinez Chaudhry • Kelly Cherry • Peter Chiykowski • Linda E. Chown • S. D. Chrostowska • Steven Church • Nicole Chu • Jeanie Chung • Alex Cigale • Sarah Clancy • Jane Clarke • Sheela Clary • Christy Clothier • Carrie Cogan • Ian Colford • Zazil Alaíde Collins • Tim Conley • Christy Ann Conlin • John Connell • Terry Conrad • Allan Cooper • Robert Coover • Cody Copeland • Sean Cotter • Cheryl Cowdy • Mark Cox • Dede Crane • Lynn Crosbie • Elsa Cross • S.D. Chrostowska Roger Crowley • Alan Crozier • Megan Cuilla • Alan Cunningham • Paula Cunningham • Robert Currie • Nathan Currier • Paul M. Curtis • Trinie Dalton • J. P. Dancing Bear • Lydia Davis • Taylor Davis-Van Atta • Robert Day • Sion Dayson • Martin Dean • Patrick Deeley • Katie DeGroot • Christine Dehne • Nelson Denis • Theodore Deppe • Tim Deverell • Jon Dewar • Jason DeYoung • Susanna Fabrés Díaz • Laura Michele Diener • Anne Diggory • Mary di Michele • Jeffrey Dodd • Anthony Doerr • Mary Donovan • Steve Dolph • Han Dong • Erika Dreifus • Jennifer duBois • Patricia Dubrava • Rikki Ducornet • Timothy Dugdale • Ian Duhig • Gregory Dunne • Denise Evans Durkin • Nancy Eimers • Jason Eisener • John Ekman • Okla Elliot • Shana Ellingburg • Susan Elmslie • Paul Eluard • Josh Emmons • Mathias Énard • Marina Endicott • Sebastian Ennis • Benjamin Evans • Kate Evans • Cary Fagan • Richard Farrell • Kinga Fabó • Kathy Fagan • Jared Daniel Fagen • Tom Faure • David Ferry • George Fetherling • Kate Fetherston • Laura Fine-Morrison • Patrick Findler • Melissa Fisher • Cynthia Flood • Stanley Fogel • Eric Foley • Larry Fondation • Paul Forte • Mark Foss • Tess Fragoulis • Anne Francey • Danielle Frandina • Jean-Yves Fréchette • Rodrigo Fresán • Abby Frucht • Simon Frueland • Kim Fu • Mark Frutkin • Róbert Gál • Mia Gallagher • Mavis Gallant • Andrew Gallix • Eugene K. Garber • Rosanna Garguilo • Gary Garvin • William Gass • Bill Gaston • Lise Gaston • Noah Gataveckas • Jim Gauer • Connie Gault • Edward Gauvin • Joël Gayraud • Charlie Geoghegan-Clements • Greg Gerke • Karen Gernant • Chantal Gervais • Marty Gervais • William Gillespie • Susan Gillis • Estelle Gilson • Nene Giorgadze • Renee Giovarelli • Jody Gladding • Jill Glass • Douglas Glover • Jacob Glover • Jonah Glover • Douglas Goetsch • Rigoberto González • Georgi Gospodinov • Alma Gottlieb • John Gould • Wayne Grady • Philip Graham • Richard Grant • Nowick Gray • R. W. Gray • Áine Greaney • Brad Green • Daniel Green • Henry Green • Catherine Greenwood • T. Greenwood • Darryl Gregory • Walker Griffy • Genese Grill • Rodrigo Gudiño • Genni Gunn • Richard Gwyn • Gabor G. Gyukics • Daniel Hahn • Donald Hall • Phil Hall • Nicky Harmon • Kate Hall • Susan Hall • Jane Eaton Hamilton • Elaine Handley • John Haney • Wayne J. Hankey • Julian Hanna • Jesus Hardwell • Jennica Harper • Elizabeth Harris • Meg Harris • Kenneth J. Harrison, Jr. • Richard Hartshorn • William Hathaway • Václav Havel • John Hawkes • Sheridan Hay • Bill Hayward • Hugh Hazelton • Jeet Heer • Steven Heighton • Lilliana Heker • Natali e Helberg • Olivia Hellewell • David Helwig • Maggie Helwig • Robin Hemley • Stephen Henighan • Claire Hennessy • Kay Henry • Julián Herbert • Sheila Heti • Darren Higgins • Tomoé Hill • Anne Hirondelle • Bruce Hiscock • H. L. Hix • Godfrey Ho •dee Hobsbawn-Smith • Andrej Hočevar • Jack Hodgins • Tyler Hodgins • Noy Holland • Greg Hollingshead • Dan Holmes • Cynthia Holz • Amber Homeniuk • Drew Hood • Bernard Hœpffner • Kazushi Hosaka • Gregory Howard • Tom Howard • Ray Hsu • David Huddle • Nicholas Humphries • Cynthia Huntington • Christina Hutchings • Matthew Hyde • Joel Thomas Hynes • Angel Igov • Ann Ireland • Agri Ismaïl • Mary Kathryn Jablonski • Richard Jackson • J. M. Jacobson • Fleur Jaeggy • Matthew Jakubowski • A. D. Jameson • Mark Anthony Jarman • David Jauss • Amanda Jernigan • Anna Maria Johnson • Steven David Johnson • Bill Johnston • Ben Johnstone • Cynan Jones • Julie Jones • Shane Jones • Pierre Joris • Gunilla Josephson • Gabriel Josipovici • Miranda July • Adeena Karasick • Wong Kar-Wai • Maggie Kast • Elizabeth Woodbury Kasius • Allison Kaufman • Aashish Kaul • Allan Kausch • John Keeble • Richard Kelly Kemick • Dave Kennedy • Maura Kennedy • Timothy Kercher • Jacqueline Kharouf • Anna Kim • Patrick J. Keane • Rosalie Morales Kearns • John Kelly • Victoria Kennefick • Besik Kharanauli • Daniil Kharms • Sean Kinsella • Rauan Klassnik • Lee Klein • Karl Ove Knausgaard • Montague Kobbé • James Kochalka • Wayne Koestenbaum • Ani Kopaliani • Jan Kounen • Lawrence Krauss • Fides Krucker • Kathryn Kuitenbrouwer • Anu Kumar • Sonnet L’Abbé • Yahia Lababidi • Andrea Labinger • M. Travis Lane • Zsolt Láng • Julie Larios • Mónica Lávin • Evan Lavender-Smith • Bruno LaVerdiere • Sophie M. Lavoie • Mark Lavorato • Daniel Lawless • Sydney Lea • Ang Lee • Whitney Lee • Diane Lefer • Shawna Lemay • J. Robert Lennon • Kelly Lenox • Giacomo Leopardi • Ruth Lepson • María Jesús Hernáez Lerena • Naton Leslie • Edouard Levé • Roberta Levine • Samuel Ligon • Erin Lillo • Paul Lindholdt • Leconte de Lisle • Gordon Lish • Yannis Livadas • Billie Livingston • Anne Loecher • Dave Lordan • Bojan Louis • Denise Low • Lynda Lowe • Jason Lucarelli • Zachary Rockwell Ludington • Sheryl Luna • Mark Lupinetti • Jeanette Lynes • Joanne Lyons • Andrew MacDonald • Toby MacDonald • Alexander MacLeod • Patrick Madden • John Madera • Randall A. Major • Grant Maierhofer • Keith Maillard • Mary Maillard • Edward Maitino • Rohan Maitzen • Augustín Fernández Mallo • Charlotte Mandell • Louise Manifold • Jonathan Marcantoni • Philip Marchand • Micheline Aharonian Marcom • Vincent Marcone • Josée Marcotte • Julie Marden • Jill Margo • Dave Margoshes • Nicole Markotić • China Marks • André Marois • Jennifer Marquart • Toni Marques • Lucrecia Martel • Deborah Martens • Casper Martin • Cynthia Newberry Martin • Harry Marten • Rebecca Martin • Rick Martin • Ilyana Martinez • Michael Martone • Nicola Masciandaro • Momina Masood • Brook Matson • Melissa Matthewson • Lucy M. May • Stephen May • Micheline Maylor • Marilyn McCabe • Kate McCahill • Thomas McCarthy • Jaki McCarrick • Sharon McCartney • Clint McCown • Margie McDonald • Joseph McElroy • Cassidy McFadzean • Afric McGlinchy • rob mclennan • Paul McMahon • Ross McMeekin • Eoin McNamee • Paul McQuade • Zoë Meager • Ruth Meehan • Court Merrigan • Erica Mihálycsa • Joe Milan • Chris Milk • Billy Mills • Robert Miner • Erika Mihálycsa • Eugene Mirabelli • Rossend Bonás Miró • Salvador Díaz Mirón • Mark Jay Mirsky • Peter Mishler • Michelle Mitchell-Foust • Brenda McKeon • Ariane Miyasaki • Eric Moe • Susie Moloney • Quim Monzó • Jung Young Moon • Jacob McArthur Mooney • Martin Mooney • Gary Moore • Steven Moore • k. a. Moritz • Adam Morris • Keith Lee Morris • Garry Thomas Morse • Erin Morton • Diane Moser • Sarah Moss• Warren Motte • Horacio Castellanos Moya • Guilio Mozzi • Greg Mulcahy • Karen Mulhallen • Gwen Mullins • Hilary Mullins • Andres Muschietti • Robert Musil • Jack Myers • Jean-Luc Nancy • John Nazarenko • David Need • Rik Nelson • Pierre Nepveu • Joshua Neuhouser • Nezahualcóyótl • Levi Nicholat • Nuala Ní Chonchúir • Lorinne Niedecker • Doireann Ní Ghríofa • Christopher Noel • João Gilberto Noll • Lindsay Norville • Franci Novak • Margaret Nowaczyk • Masande Ntshanga • Michael Oatman • Gina Occhiogrosso • Carolyn Ogburn • Timothy Ogene • Kristin Ohman • Megan Okkerse • Susan Olding • Óscar Oliva • Robin Oliveira • Lance Olsen • William Olsen • Barrett Olson-Glover • JC Olsthoorn • Ondjaki • Chika Onyenezi • Patrick O’Reilly • Kay O’Rourke • David Ishaya Osu • John Oughton • Kathy Page • Victoria Palermo • Benjamin Paloff • Yeniffer Pang-Chung • Kathryn Para • Alan Michael Parker • Lewis Parker • Jacob Paul • Cesar Pavese • Keith Payne • Gilles Pellerin • Paul Perilli • Martha Petersen • Pamela Petro • Paul Pines • Pedro Pires • Álvaro Pombo • Jean Portante • Garry Craig Powell • Alison Prine • Sean Preston • John Proctor • Tracy Proctor • Dawn Promislow • Emily Pulfer-Terino • Jennifer Pun • Lynne Quarmby • Donald Quist • Leanne Radojkovich • Dawn Raffel • Heather Ramsay • Rein Raud • Michael Ray • Hilda Raz • Victoria Redel • Kate Reuther • Julie Reverb • Shane Rhodes • Adrian Rice • Matthew Rice • Jamie Richards • Barbara Richardson • Frank Richardson • Mary Rickert • Brendan Riley • Sean Riley • Rainer Maria Rilke • Maria Rivera • Mark Reamy • Nela Rio • David Rivard • Isandra Collazo Rivera • Mary François Rockcastle • Angela Rodel • Johannah Rodgers • Pedro Carmona Rodríguez • Ricardo Félix Rodriguez • Jeanne Rogers • Matt Rogers • Lisa Roney • Leon Rooke • Marilyn R. Rosenberg • Rob Ross • Jess Row • Shambhavi Roy • Mary Ruefle • Chris Russell • Laura-Rose Russell • Ethan Rutherford • Ingrid Ruthig • Tatiana Ryckman • Mary H. Auerbach Rykov • Umberto Saba • Juan José Saer • Stig Sæterbakken • Trey Sager • Andrew Salgado • José Luis Sampedro • Cynthia Sample • Mark Sampson • Jean-Marie Saporito • Maya Sarishvilli • Natalia Sarkissian • Dušan Šarotar • Paul Sattler • Sam Savage • Igiaba Scego • Michael Schatte • Boel Schenlaer • Bradley Schmidt • Elizabeth Schmuhl • Diane Schoemperlen • Joseph Schreiber • Steven Schwartz • Sophfronia Scott • Sarah Scout • Fernando Sdrigotti • Sea Wolf • Mihail Sebastian • Jessica Sequeira • Adam Segal • Mauricio Segura • Shawn Selway • Sarah Seltzer • Maria Sledmere • K. E. Semmel • Robert Semeniuk • Ivan Seng • Pierre Senges • Shelagh Shapiro • Mary Shartle • Eamonn Sheehy • David Shields • Mahtem Shifferaw • Betsy Sholl • Viktor Shklovsky • David Short • Jacob Siefring • Germán Sierra • Eleni Sikelianos • Paul-Armand Silvestre • Goran Simić • James Simmons • Janice Fitzpatrick Simmons • Thomas Simpson • George Singleton • Taryn Sirove • Richard Skinner • SlimTwig • Ben Slotsky • Ariel Smart • Jordan Smith • Kathryn Smith • Maggie Smith • Michael V. Smith • Russell Smith • John Solaperto • Glen Sorestad • Stephen Sparks • D. M. Spitzer • Matthew Stadler • Erin Stagg • Albena Stambolova • Domenic Stansberry • Maura Stanton • Andrzej Stasiuk • Lorin Stein • Mary Stein • Pamela Stewart • Samuel Stolton • Bianca Stone • Bruce Stone • Nathan Storring • John Stout • Darin Strauss • Marjan Strojan • Dao Strom • Cordelia Strube • Dorian Stuber • Andrew F. Sullivan • Spencer Susser • Lawrence Sutin • Terese Svoboda • Gladys Swan • Paula Swicher • George Szirtes • Javier Taboada • Antonio Tabucchi • Zsuzsa Takács • Emili Teixidor • Habib Tengour • Leona Theis • This Is It Collective • Dylan Thomas • Elizabeth Thomas • Hugh Thomas • Lee D. Thompson • Melinda Thomsen • Lynne Tillman • Jean-Philippe Toussaint • Joyce Townsend • Jamie Travis • Julie Trimingham • Ingrid Valencia • Valentin Trukhanenko • Marina Tsvetaeva • Tom Tykwer • Leslie Ullman • Kali VanBaale • Felicia Van Bork • Will Vanderhyden • Charlie Vázquez • Manuel de Jesus Velásquez Léon • S. E. Venart • Rich Villar • Adèle Van Reeth • Nance Van Winckel • Louise Lévêque de Vilmorin • Katie Vibert • Robert Vivian • Liam Volke • Laura Von Rosk • Wendy Voorsanger • Miles Waggener • Catherine Walsh • Joanna Walsh • Wang Ping • Paul Warham • Laura K. Warrell • Brad Watson • Richard Weiner • Roger Weingarten • Tom Pecore Weso • Summar West • Adam Westra • Haijo Westra • Darryl Whetter • Chaulky White • Curtis White • Derek White • Mary Jane White • Diana Whitney • Dan Wilcox • Cheryl Wilder • Tess Wiley • Myler Wilkinson • Diane Williams • Deborah Willis • Eliot Khalil Wilson • Donald Winkler • Colin Winette • Dirk Winterbach • Ingrid Winterbach • Tiara Winter-Schorr • Quintan Ana Wiskwo • David Wojahn • Macdara Woods • Ror Wolf • Benjamin Woodard • Angela Woodward • Russell Working • Liz Worth • Robert Wrigley • Xu Xi • Can Xue • Jung Yewon • Chen Zeping • David Zieroth • Deborah Zlotsky

.o

o

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.