Sexual life belongs almost entirely to that “invisible part” of our existence—I’d say it constitutes our “third life,” along with the daily, conscious one, and with the one we conduct in our dreams. So, what particularly tantalized me while working on the book was to examine precisely how that massive, dark, and powerful mainstream of history affects, quite surreptitiously, people’s most unconscious behavior, words and gestures produced in bed. — Oksana Zabuzhko

Oksana Zabuzhko

Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex

Translated by Halyna Hyrn

AmazonCrossing, 2011

164pp; $13.95

Since the it was first published in 1996, Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex has become one of the most controversial and best-selling novels in Ukraine in the last twenty years. Oksana Zabuzhko is a poetic genius (and she is foremost a poet), and Fieldwork reads as if it were one long poem. The novel is not divided into conventional chapters. Instead serpentine, run-on sentences fluidly slide into side-thoughts contained in brackets and small passages of verse, so the reader enters and re-enters the book in an endless series of apparently chaotic yet somehow seamless stream-of-consciousness thoughts.

Fieldwork, finally published in English last year by AmazonCrossing, Amazon’s new in-house translation imprint, has largely been heralded as an autobiographical novel by critics, though Zabuzhko maintains it is anything but autobiography. The protagonist, a clever, highly talented and nameless poet, does echo Zabuzhko herself (for example, the poet narrator travels from Ukraine to America as Zabuzhko has done), but that’s where the similarities end. On the surface, the plot is very simple: the narrator tells the story of her recently ended relationship with a Ukrainian artist. However the text becomes more complex, swells and spreads like a bruise, as the poet delves into the abuse she suffered as well as the love she felt during the relationship. She struggles to come to terms with her complex grief, and as she does so she begins to unravel also the intricacies of her Ukrainian identity. The history of the affair is mapped out in the context of the history of the Ukraine, and the cartography of cultural influence and identity is perhaps more clearly revealed than the successes and failings of the relationship itself.

Zabuzhko blends the art of writing a novel with the art of poetry in a manner reminiscent of Michael Ondaatje’s also poetic novel Coming Through Slaughter. The unconventional form of the poetic novel may turn off some readers as it is more intensely intimate, difficult, captivating and implicating than the popular conventionally realistic novel. Experiencing Fieldwork is not an exercise in reading for entertainment but rather reading for discovery, reading for a sensual feeling of pain and proximity, and reading to learn about and hold the immediacy of contemporary Ukrainian culture and language and its historic burdens.

Zabuzhko has said, “…poets are and will always remain the guardians of a language, which every society tries to contaminate with lies of its own. Unlike novelists, who may be pigeonholed as opinion-makers, poets are seldom interviewed by media on political and moral issues, yet in the end it’s they who remain responsible for the very human capacity to opine. They keep our language alive.”

Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex is about keeping a language and culture alive — one the narrator desperately tries to revive, to heal as if it is a diseased body. The ramifications of the state of Ukrainian culture play out on the narrator’s body, a fractured body – pieces of her immediate self are referred to in the third person; her own body, read as metaphor for her country, is like a strange, alien “other” that she must try to revive over and over despite the history and trauma that encroach on her and try to consume her.

To read Zabuzhko’s Fieldwork in Ukrainian Sex is to be constricted and devoured by a serpent. Beautiful, shining scales and the soft, rippling muscle of the snake surround you, slide against your skin, light refracting like off gasoline on water, and suddenly the crushing weight of remembered cultural history is upon you and unbearable, and you can feel yourself collapsing into it, devoured by it, and truly becoming a part of it — Ukrainian history and cultural identity eats you alive, because after all, “Ukrainian choice is a choice between nonexistence and an existence that kills you.”

Ukraine has a long history of being divided and re-united again and again. Parts of modern-day Ukraine were once considered, by turns, Russian and Polish and German. Ukrainian language after the demise of Soviet rule was nearly dead — a complication for many when, after independence, it was suddenly made the official language once more. Ukraine has been called “the bloodlands,” the slaughterfield between Hitler and Stalin in WWII. More recently it has become known as a radiated wasteland after the Chernobyl disaster in 1986.

As a woman born into a Soviet-ruled Ukraine and who watched the fall of the USSR and the birth of Ukrainian independence, Zabuzhko’s undertaking in analyzing what it means to be Ukrainian through her novel is both excruciating and stunning. The analysis is largely accomplished via metaphor; the narrator’s overriding concern is her tumultuous, passionate and abusive relationship and her final escape from her Ukrainian male lover. Her narrative style is unconventional — Zabuzhko slides between first, second and third person narratives throughout, a tactic that echoes the fragmented self and fragmented identity of every Ukrainian. The three points of view also mirror the id, ego, and superego of Freudian psychology — and this is a psychological novel.

Zabuzhko is highly aware of this psychological aspect, the dark and repressed parts of Ukrainian history and identity, and yet she is equally aware of a the transformative potential. Culture, after all, is always subject to change even when burdened with the weight of a past. In an interview with Ruth O’Callaghan in Poetry Review, Zabuzhko said :

I argue that telling the truth — bringing to the spotlight of people’s consciousness what’s been previously in shadow, whatever it may be — has been, and will always be, a risky job, for as long as human society exists: if only because, in pronouncing certain truths for the first time, you inevitably attack the whole set of psychological, mental, and verbal stereotypes which were disguising it.

Of course, many Ukrainian critics have vilified Zabuzhko for her assault on the subconscious dark side of Ukrainian identity, but others all but canonized her. Fieldwork has been called a Ukrainain Feminist Bible (Zabuzkho has been called the Ukrainain Sylvia Plath). But Zabuzhko herself has said she prefers to not differentiate her readers along gender lines. Her approach in the novel, although undeniably from the perspective of a woman and certainly bleeding with feminist thought, is broader in scope. “What I attacked,” she once said, “was, basically, a system of social lies extending to the point of mental rape, and affecting both men and women.”

The narrator’s abusive love affair reflects the abusive nature of historical cultural norms and imposed values in Ukraine. It symbolizes a generation’s struggle to free itself from the past, to forge its own identity, and yet hold onto the best parts of the former identity, the traditions and historical moments that made independence worth fighting for despite years of being suspended between wars, languages, identities, and hostile neighbours that would crush, assimilate or extinguish them. Thus the narrator reflects on the tenderness and love that was present in her relationship as much as the painful parts, the destructive parts, and the unbearable and everlasting scars that remain.

So much of the novel is frantically looking for an exit, some way to escape a collective cultural past by turns shameful and exhilarating. Zabuzhko’s narrator, like the reader, ultimately discovers a home in her culture and language despite its lethality:

…obviously her mother tongue was the most nutritious, most healing to the senses: velvety marigold, or no, cherry (juice on lips)? strawberry blond (smell of hair)? …it’s always like that, the minute you peer more closely the whole thing disintegrates into tiny pieces and there’s no putting it back together; she hungered for her language terribly, physically, like a thirsty man for water, just to hear it — living and full-bodied with that ringing intonation like a babbling brook at at distance…

The way language is described here — as sensual nourishment, as healing, and yet fragmented and longed for — is typical of the novel as a whole. The longing for something loved and dangerous is at the book’s core. And yet are not all cultural identities like this? Do they not all have their destructive, oppressive and damaging histories that we must embrace and attempt to transform?

Fieldword opens a wound within the reader. Suddenly, the historical trauma passed down from generation to generation becomes clear and inescapable. Although the word “Gulag” is only used twice, in one of the small snippets of poetry peppered throughout the novel, the vast system of Stalinist concentration camps is present, quiet and ghost-like, throughout the narrative.

We are all from the camps. That heritage will be with us for a hundred years.

And, though the crux of the novel is Ukrainian identity, the book is not exclusively about being Ukrainian. It’s about being on your knees under the weight of any culture. The narrator wryly observes the same struggle in America. “… the Great American Depression from which it seems that about 70 percent of the population suffers, running to psychiatrists, gulping down Prozac, each nation goes crazy in its own way…”

This is a novel that digests its reader; you feel as if you are becoming fluid — dissolved into something at once more complete and yet more disjointed. The novel consumes you until it is fat with you, until you become subsumed in its pain and sensuality and it is about to burst with you (and not the other way around) — because it is rich with poetry and consciousness and what it means to be human. The effect is not pleasant completely, it is intense, a half-surrender to something, a journey or a quest for a meaning you can’t find and don’t understand.

—Brianna Berbenuik

See also Oksana Zabuzhko in an interview with Halyna Hryn for AGNI Online.

——————————————-

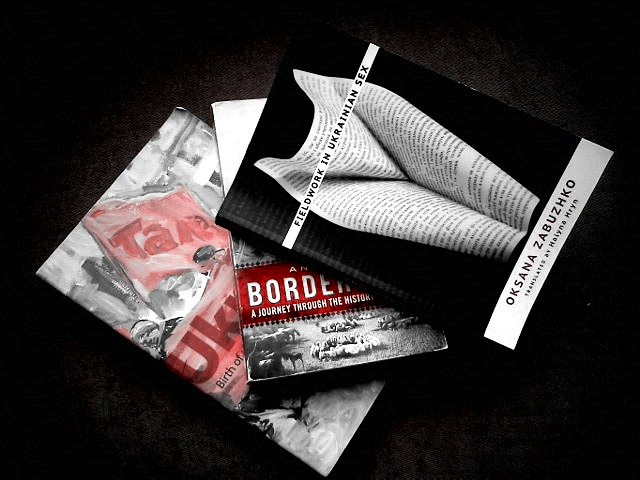

Brianna Berbenuik is a 20-something misanthropist and student of Slavic Studies at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. She is an avid fan of kitschy pop-culture, terrible Nic Cage movies, the philosophy of Slavoj Zizek, and Freud. You can find her at Love & Darkness & My Side-Arm on her twitter account where she goes by ukrainiak47. She wishes to express her gratitude to the poet Olga Pressitch and Serhy Yekelchyk, who both teach at the University of Victoria in the Department of Slavic Studies. for their tutelage and passion about Ukrainian history, language and culture. “Without their courses I wouldn’t have a grip on half of what I do when it came to this particular review, and Olga is the reason I wanted to read the novel in the first place.” Also the book you see in the photo, the bottom one, called Ukraine, is a comprehensive history written by Serhy.

Brianna Berbenuik is a 20-something misanthropist and student of Slavic Studies at the University of Victoria in British Columbia. She is an avid fan of kitschy pop-culture, terrible Nic Cage movies, the philosophy of Slavoj Zizek, and Freud. You can find her at Love & Darkness & My Side-Arm on her twitter account where she goes by ukrainiak47. She wishes to express her gratitude to the poet Olga Pressitch and Serhy Yekelchyk, who both teach at the University of Victoria in the Department of Slavic Studies. for their tutelage and passion about Ukrainian history, language and culture. “Without their courses I wouldn’t have a grip on half of what I do when it came to this particular review, and Olga is the reason I wanted to read the novel in the first place.” Also the book you see in the photo, the bottom one, called Ukraine, is a comprehensive history written by Serhy.

Born in the Western Ukrainian city of Lutsk in 1960, into a Ukraine under the rule of the USSR, Oksana Zabuzhko grew up Kyiv and went on to study philosophy at Shevchenko University, graduating in 1992 (a year after the collapse of the Soviet Union). She spent time in America teaching at Penn State University and won a Fulbright Scholarship in 1994. She has lectured in the United States on Ukrainian culture at Harvard and the University of Pittsburg.

Halyna Hryn is a lecturer in Ukrainain Culture and Language at Yale University since 1996.

Terrific review. Thanks for bringing this novel to my attention.