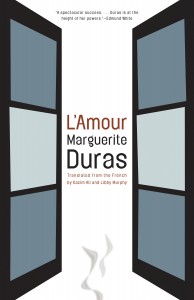

L’Amour

Marguerite Duras

Introduction by Kazim Ali

Afterword by Sharon Willis

Translated from the French by Kazim Ali and Libby Murphy

Open Letter Books, 109 pp. $12.95

Reading Marguerite Duras’s short novel L’Amour, written in 1971 and translated for the first time into English with this 2013 Open Letter edition, is like watching a film of silvery images unwind against a muted seascape of sand and salt. An occasional flash of color punctuates. Blue eyes. Green plants. A pink dawn. And throughout the novel the nameless survivors of concealed histories—The Man Who Walks, The Woman With Closed Eyes, The Traveler—group and regroup on the beach, along the river and in the mythical town of S. Thala in a never-ending, enigmatic dance of desire and entanglement.

In a world where secrets are manifest but never revealed, Duras’ rendering of the painful aftermath of aborted love takes the form of a tortured tango in which the three protagonists take part.

At the outset of the novel the author silhouettes two words against the page, a sentence fragment which freezes the image of a man against an uncertain backdrop:

A man.

Standing, watching: the beach, the sea. The sea is calm, flat; season indefinite, moment lingering.

The man stands on a boardwalk over the sand.

He wears dark clothes. His face distinct.

His eyes clear.

He does not move. He watches.

The sea, the beach, a few tidal pools, flat surfaces of water….

But the lens then widens to reveal that this man, The Traveler, is not alone. Far off, between The Traveler and the sea, at the edge of the water, strides another man: ‘The Man Who Walks.’

Between the man who watches and the sea, far off, all the way at the water’s edge, someone walking. Another man. Wearing dark clothes. From here his face is indistinct. He walks, going, coming, he goes, comes again, his path is rather long, never changing….[3]

To the left of the Traveler, The Woman With Closed Eyes sits against the stone wall that separates the beach from the town:

The triangle is completed by the woman with closed eyes. She is sitting against the wall that separates the beach from the town.

The man who watches is between this woman and the man who walks along the edge of the sea.

Because of the man who walks, constantly with his slow even

stride, the triangle stretches long, reforms, but never breaks.

This man has the even steps of a prisoner….

The three-sided tango begins. At first static, the triangle shifts and comes undone, reforms and comes apart, and then reforms again as the characters move through space.

The man is still walking, coming, going, before the sea, the sky, but the man who was watching has moved.

The even sliding of the triangle ceases.

He moves.

He begins to walk.

Someone walks, nearby.

The man who was watching passes between the woman with closed eyes and the other, far away, the one who goes, who comes, a prisoner. You hear the hammering of his steps on the boardwalk.

His steps are uneven, hesitant.

The triangle comes undone, reforms. [4-5]

In continual flux, this shape-changing triangle is the foundation of the novel; it is both metaphor and metonym that eliminates the need for explanation. The reader learns only that The Traveler, having abandoned his wife and children, returns to S. Thala to commit suicide. The Woman With Closed Eyes lives in a prison-like institution; she is followed by a mad caretaker, The Man Who Walks. The story that involves them “began before the walk along the edge of the sea” in the opening pages. As the sea has washed the sands in the interim, so has time washed memory from the minds of the characters.

Several other characters appear briefly in the novel; these include two women who meet with The Traveler. They allude to previous affairs and to other, long-disbanded triangles. But it is to The Woman With Closed Eyes that The Traveler returns. With her, he attempts to undertake a voyage to the center of town to recover memory; as a result, “a peak of intensity” is reached. [1] The woman dresses in white and carries a handbag that contains nothing but a mirror. Vague recollections surface: the woman’s eighteenth summer, her children, her dead husband and how the town of S. Thala used to be. There is, however, no release. The memories prove to be too spare. Neither the characters nor the reader can fully understand. When the sun becomes too hot and the effort of remembering too much, the woman collapses on the beach, stretches out, does not move. She falls asleep and The Traveler sprinkles sand over her body. He pronounces the word “Love,” in a truncated dialogue which elicits no response: [2]

Her eyes open, they look without seeing, without recognizing anything, then close again, fade to black. [84]

Soon thereafter, the man who walks returns from his wanderings and sets fire to the town of S. Thala; by destroying the town, he empties the novel; all that is left is the sand and sea and another day without significance.

Dialogue throughout the novel enhances this aesthetic of estrangement; it is short, discrete and disconnected. Often a series of non sequiturs, conversation barely functions as communication; instead it seems to be a “faltering counterpoint of sound and silence.” [3]

Transitions between paragraphs—the book’s chapters—are likewise abrupt. Words that resemble stage directions indicate shifts in time or place. Moreover, by embedding scenes within a frame of white space on the page, Duras creates discrete units, the cumulative effect of which is a series of images flashing across the page. The reader bears witness to the morphing geometry of the dance as if flipping through a photo album or watching a film.

Yet the description of setting—especially of the beach—is lush. Indeed, Duras’ rendition of the elements often draws attention away from the trio on the beach, dissolving them. Consider:

Day dwindling.

The sea, the sky, fill the space. Far off, the sea, like the sky, already oxidized by the shadowy light.

Three, three in the shadowy light, a slow-shifting web.

And:

Somewhere on the beach, to the right of the one who watches, a movement of light: a pool empties, a spring, a stream, many-mouthed streams, feeding the abyss of salt.

This is gorgeous writing that creates a metaphor of the environment, a shifting, modulating, oxidizing world of relations.

In the introduction to this edition Kazim Ali writes that “the starkness of tone and flatness of delivery may be why” L’Amour has never before been translated into English. But he also points out that “the stillness of the text and the static nature of its characters is a deception—it is full of movement, people shifting form place to place, endlessly moving like the sea.”

In fact, as Sharon Willis illustrates in the afterword, a chief technical problem in translating the work was how to present the “rich palette of variation of verbs that only French can provide.” English relies on prepositions and lacks the movement inherent in French. Revenir is translated with three words in English: ‘to come back,’ and retourner with ‘to go back.’

Written midway during an illustrious and prolific career that spanned more than five decades and earned Duras numerous honors including the 1984 Prix Goncourt for L’Amant, L’Amour is at the core of a group of Duras’ works dubbed the “India cycle.” This body of work includes the novels Le Ravissement de Lol V. Stein (1964) and Le Vice-Consul (1965) as well as the films La Femme du Gange (1972—the adaptation of L’Amour) and India Song (1974—from Le Vice-Consul); the primary event from which the India cycle works spring is the betrayal of the character, Lol V. Stein by her lover.[4]

L’Amour recalls the earlier novel by reworking the material, but it does so in a fragmented manner. The Woman With Closed Eyes on the beach in L’Amour seems to resemble Lol V. Stein but, as we’ve seen, she remains nameless. The traveler is possibly Michael Richardson, the lover who abandoned Lol for an older woman, but in L’Amour this is also unspecified. The name of the fictional, coastal town—S. Thala—is the same in both (although the early English translations of Le Ravissement mistranslated it as South Thala).

In the same way, Duras renders descriptions, history, plot, and analysis—novel thought—ghostly or non-existent. Stripped of layers, the characters in L’Amour do not reflect on where they’ve been, where they are and where they are going; nor do they feel. Their world has been bled of much color and sound; it is a black and white space where, in the words of Duras, “breath is rarified and sensory experience is diminished.”[5] Their world emptied, the characters are caught in a void.[6]

L’Amour is, in fact, a revolutionary text, one in which Duras grappled with the issue she faced as an avant-garde artist interested in rendering Roland Barthes’ zero point. This, for her, was where “the intolerable emptiness of the text forces recognition of the need for the recovery of sensitivity.”[7] In order to reach the zero point in L’Amour, not only does Duras depict disintegration in the pages of her novel, but along the way she destroys “the most precious theme of Western fiction, the love story, and the structure of the bourgeois novel.”[8] The seamless creation of the realist writer writhes on the operating table as Duras wields her scalpel.

After L’Amour, Duras turned the flame up on her experimentation. She believed she could write more radically in film because in film, “tout est écrit”.[9] Thus, when she moved on to La Femme du Gange, “through a continual and unswerving shift, she passed from words on a page to images on a screen; [From fiction to film] discourse is muffled, concrete representation of reality is reduced to fragmented materiality and finally to full darkness projected into the space of a given screen.”[10]

Thus, just as L’Amour echoes an earlier text, it also gives rise to works that continue to experiment with rendering the void; these in the medium of film. But by supplying actual footage in lieu of text, Duras ultimately succeeds in subverting another triangle; that of the reader, the narrative and immersion in a world that seems not to have been constructed but to have always existed.[11]

—Natalia Sarkissian

Sources:

Borgomanero, Madeleine. “L’Ecriture Filmique de Marguerite Duras, Review by Yuri Vidov Karageorge.” The French Review, 61, no. 4 (March 1988): 641

Duras, Marguerite. “An Interview with Marguerite Duras” (conducted by Germaine Bree), tr. Cyril Doherty, Contemporary Literature, 13 (1972), 427.

Duras, Marguerite. Les Cahiers. Paris: Gallimard, 1971.

Duras, Marguerite and Xaviere Gauthier. Les Parleuses. Paris: Editions de Minuit, 1974, p. 12.

Gaensbauer, Deborah B. “Revolutionary Writing in Marguerite Duras’ L’Amour,” The French Review, 55, No. 5 (April 1982): 633-639.

Josipovici, Gabriel. Whatever Happened to Modernism? New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

McNeece, Lucy Stone. “The Reader in the Field of Rye: Marguerite Duras’ L’Amour,” Modern Language Studies, 22. No. 1 (Winter, 1992): 3-16.

Nichols, Stephen G., Jr. “Writing Degree Zero by Roland Barthes,” Contemporary Literature, University of Wisconsin Press, 10, No. 1 (Winter, 1969): 136-146.

————————————————–

Natalia Sarkissian has an MFA in Writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts and has been an editor and contributor at Numéro Cinq since 2010. Natalia divides her time between Italy and the United States.

- Gaensbauer, 637↵

- See Gaensbauer, 637↵

- McNeece, 7↵

- McNeece, 5↵

- Duras, Les Parleuses, cited by Gaensbauer, 636↵

- Gaensbauer, 636; McNeece 4↵

- Gaensbauer, 633↵

- Gaensbauer, 633↵

- Duras, 1977, p. 90-cited in McNeece, 14↵

- Borgomano, Madeleine. L’écriture filmique de Marguerite Duras—Book Review by Yuri Vidov Karageorge in The French Review p. 641↵

- Josipovici, p 166↵

I didn’t realize there were more Duras books to be published in English. I’m quite excited to check this out. Reading Duras is a unique experience – like a dream state of quiet emotions, repetitions and with timeframes and settings that change and yet seem the same. And so many of her novels seem like yet another exploration of the same characters and themes – very hypnotic.