Casper David Friedrich, The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, 1818, Courtesy of Wikipedia

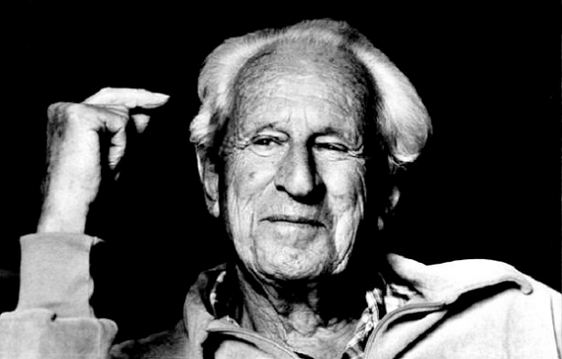

Contributing Editor Pat Keane goes from strength to strength; sometimes I feel that inviting him to write for NC I unleashed one of those Platonic demons — a torrent of thought, word, reference, and wit has erupted. This time he has outdone himself — “Mountain Visions and Imaginative Usurpations” is my favourite of his essays so far. He begins with Columbus sighting America but only uses that as an occasion, as a peg upon which to weave a gorgeous meditation on mountains, mountains in literature, sublimity, and poetry. Pat has more than a way with words and the gift of intelligence; he has vast reading and an astonishing memory — he seems to live in a house of words (in his mind), reaching this quotation and that off the shelf at will. Focused primarily on Wordsworth’s The Prelude, the essay leaps also from Petrarch (climbing a mountain) to Augustine, to Keats, to Yeats (“Lapis Lazuli” — see image below), to Emerson, to Kant and Nietzsche, and every reference is cited with intimate familiarity as if the author’s mind and the culture of ideas have somehow melded (think Vulcan mind-meld). Such feats are a deep pleasure in the reading. Hell, I am editing and publishing this AND I keep taking notes on the side for myself.

dg

1

This essay was completed on the first day of October, 2012. Five hundred and twenty years ago almost to the day, a man saw something, a kind of vision. “About 10 o’clock at night, while standing on the sterncastle, I thought I saw a light to the west. It looked like a little wax candle bobbing up and down….The moon, in its third quarter, rose in the east shortly before midnight…. Then, two hours after midnight, the Pinta fired a cannon, my prearranged signal for the sighting of land. I now believe that the light I saw earlier was a sign from God and that it was truly the first positive indication of land.” The flash of light Christopher Columbus saw from the sterncastle of the Santa Maria on the night of October 11, 1492, transformed human history, mostly if not always for good. Even for those of us open to the ideal vision of America as a City on a Hill, or as earth’s last best hope, there are moments when mindless chants of “USA! USA!,” accompanied by an increasingly jingoistic insistence on American “exceptionalism,” make us appreciate, if not quite endorse, Mark Twain’s sardonic entry for the traditional date in Pudd’nhead Wilson’s Calendar: “THE DISCOVERY. It was wonderful to find America, but it would have been even more wonderful to miss it.”

Columbus’s Diario or log reveals a man of single-minded intensity, though hardly one with the elevated perspective marking the genuine visionary. I’m interested on this occasion in what I’m calling mountain vision; and, symbolically speaking, Columbus’s shipboard tower or sterncastle simply wasn’t high enough. He took the Bahamas for China and Cuba for Japan, and can hardly be said (anymore than the Norsemen 500 years earlier) to have “discovered” a world populated for millennia by native peoples, for whom Columbus’s voyage proved to be anything but a “sign from God”—emerging, instead, as a negative form of what William Wordsworth, describing the relation between the physical sight of mountains and the transforming power of imagination, termed “usurpation.”

And yet, in the full sense of the word, it was obviously “wonderful” to find America. The European Renaissance, an exciting Age of Exploration and Discovery, had a kind of rebirth in the Romantic period, which in many ways replicated that earlier explosion of science, exploration, and wonder-struck literature. The title of Richard Holmes’s splendid 2008 book seems inevitable: The Age of Wonder: How the Romantic Generation Discovered the Beauty and Terror of Science. The discoveries discussed by Holmes—by men like Joseph Banks, William Herschel, and Humphry Davy—were, of course, anticipated by the discoveries of such Renaissance and post-Renaissance men as Robert Hooke, Andreas Vesalius, and Isaac Newton. As if to confirm the link between the two Ages, Wordsworth added some lines to the epic poem that would be posthumously published as The Prelude. Recalling the statue of Newton at Cambridge, “with his prism and his silent face,” the poet paid tribute to the range of Newton’s extraordinary and solitary genius: “The marble index of a mind for ever/ Voyaging through strange seas of Thought, alone” (III.62-63).

Wordsworth added those magnificent lines in 1838. In October, 1816, a younger Romantic poet, John Keats, evoked an adventurous quest for knowledge resembling that attributed by Wordsworth to Newton, and also connecting Romantic-era science with the age of European Discovery. Writing more than three centuries after Columbus, the young Keats unforgettably recaptured that initial sense of wondrous exploration and revelation. In the octave of his sonnet “On First Looking into Chapman’s Homer,” Keats depicts himself as an explorer of “goodly states” and islands dedicated to the god of poetry. But for a young reader ignorant of Greek a vast continent or ocean lay unexplored:

Much have I travelled in the realms of gold,

………..And many goodly states and kingdoms seen;

………..Round many western islands have I been

Which bards in fealty to Apollo hold.

Oft of one wide expanse had I been told

………..That deep-browed Homer ruled as his demesne;

………..Yet never did I breathe its pure serene

Till I heard Chapman speak out loud and bold.

Seeking analogues to express the sense of unexpected discovery he experienced on first reading Homer in the vigorous Elizabethan translation of George Chapman, Keats, in the sestet, deploys ocular images, astronomical and exploratory, of sudden revelation, stunned vision. He begins by evoking the discovery in 1781 of the planet Uranus by William Herschel, about which Keats had read in a book given him as a school prize: “Then felt I like some watcher of the skies/ When a new planet swims into his ken…”

But his second and clinching simile reflects his reading about geographical discovery in the Americas. Keats may, like Columbus, have been mistaken in details—it was not Cortez but Balboa who looked out upon the unexpected Pacific from the mountain at the Isthmus of Panama. But no one has better captured the awestruck moment of mountain vision, of revelation from the heights. Keats envisions the heroic conquistadore,

…………………….when with eagle eyes

…………..He stared at the Pacific—and all his men

Looked at each other with a wild surmise—

…………..Silent, upon a peak in Darien.

Poetic technique and form alone cannot account for that breakthrough into the Sublime—the assonance, alliteration, and double caesura that produce that final catch-in-the-breath moment, with its attendant sense of monumental tranquility. Nevertheless, it seems appropriate that Keats should cast his revelation in the form of a Petrarchan sonnet (rhymed abbaabba cdcdcd). The Italian Renaissance humanist, poet, and scholar Francesco Petrarca not only established an enduring form for the sonnet; he may be said to have initiated the modern sense of mountain vision. Keats depicts the discoverer and his men atop Mount Darien, that peak on the Isthmus of Panama. On April 26, 1336, Petrarch and his brother climbed a 6,000 foot peak, Mount Ventoux. His “only motive” for making “the ascent of the highest mountain in the region,” he writes a friend, “was the wish to see what so great an elevation had to offer.” In his letter he describes the ascent in realistic detail. Unlike his brother, Petrarch tried easier, more circuitous paths up the mountain before realizing that, ultimately, he had to face the difficult ordeal of a tough vertical climb. Suspended between Medieval allegory, Renaissance symbolism, and the sheer exertion and exhilaration of the climb and the final prospect from the heights, Petrarch gives us a version of the old dialogue between body and soul, flesh and spirit, the outer and the inner worlds. In short, the climb, as literary as it is actual, is a spiritual as well as a physical ascent; and in describing it the great humanist pays no less tribute to the classical writers of pagan antiquity than he does to Christian saints.

Appropriately, however, since the friend to whom he wrote this letter was an Augustinian monk, Petrarch emphasizes Saint Augustine, a small-sized codex copy of whose Confessions, given him by his friend, he took with him on his ascent. Once atop the mountain, Petrarch took out the book and, he swears, opened the text (as Augustine himself famously had, turning at random to Romans XIII.13:13-14, at the moment of his conversion) to a revelatory passage. The words Petrarch opened to occur at Confessions, X. viii. 15: “And men go about to wonder at the heights of the mountains, and the mighty waves of the sea, and the wide sweep of rivers, and the circuit of the ocean, and the revolution of the stars, but themselves they consider not.” Brooding on Augustine, Petrarch “thought in silence” of we who “neglect what is noblest in ourselves, scatter our energies in all directions, and waste ourselves in a vain show, because we look about us for what is to be found only within.” Clinching the analogy between his initially meandering route up the mountain and his final direct ascent, Petrarch ends his paysage moralisé by requesting his friend’s prayer that “these vague and wandering thoughts of mine may sometime become firmly fixed, and, after having been vainly tossed about from one interest to another, may direct themselves at last toward the single, true, certain, and everlasting good.” (Letter to Dionysio da Borga San Sepolcro)

.

2

For more than four centuries, for reasons elaborated in Marjorie Hope Nicolson’s Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory (1959), the human view from and of mountains, thought to be deformed expressions of God’s wrath, was largely eclipsed in Western literature. Perhaps recalling Moses on Sinai, John Milton has several supernatural “mountain” scenes in Paradise Lost. In Book V, his archangel Raphael, describing at Adam’s request the revolt in heaven, depicts “the Father infinite,” together with his Son, announcing his decision to appoint that Son Lord and vice-regent, “as from a flaming mount, whose top/ Brightness had made invisible.” This luminous eminence is echoed later in Book V, when Raphael envisions a third of the angelic host approaching Lucifer-Satan on his “royal seat/ High on a hill, far blazing, as a mount/ Rais’d on a mount,” with the chief of the rebelling angels “Affecting all equality with God,/ In imitation of that mount whereon/ Messiah was declar’d in sight of heaven” (V.596-99, 756-58, 764-65). Still later, in the final Book, Milton’s angel Michael, a “seer blest,” reveals the far future to fallen Adam from a height, assuring him as they descend that, thanks to the redemptive sacrifice of Christ, the Eden lost by Adam and Eve despite Raphael’s warning will be replaced by a “paradise within thee, happier far” (XIV..587).

Benjamin Robert Hayden’s 1842 portrait of Wordsworth (then 72), posed against Helvellyn Peak, a Lake District mountain (the third highest in England) often climbed by the poet). The painting was inspired by a Wordsworth sonnet commemorating one such climb.

This seems a version of the Petrarchan quest for “what is to be found only within.” But it took Milton’s great heir, William Wordsworth, to return poetry to human heights and to secularly redeem the false sense of “divinity within,” an autonomous instinct that proved lethal to Adam and Eve (Paradise Lost IX. 1010), but which defines the creative Imagination for poets in the Romantic tradition. Naturalizing supernaturalism, and fusing the power of Milton, and of Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant on the Beautiful and the Sublime, with his own climbing experiences in the mountainous Lake District of England, in Wales, and in the French Alps, Wordsworth gives us, at two climactic moments of his autobiographical epic, The Prelude, unforgettable examples of mountain vision.

Those symbolic moments (in Books VI and XIV) are foreshadowed in the opening Book. Dramatizing the fair seed-time in which he “grew up/Fostered alike by beauty and by fear,” Wordsworth describes, among his boyish sports, stealing birds’ eggs from mountain nests. Though the object was “mean,” the outcome “was not ignoble.” In a terrifying but thrilling moment of enhanced sensory apprehension, the solitary climber, hung perilously on the cliff, is caught up in that sublime “motion” that, for Wordsworth, animates the vital universe. The descriptions are virtually identical in the 1805 (lines 341-50) and 1850 (lines 330-39) versions of The Prelude. Here I cite the 1850 text:

……………….Oh! When I have hung

Above the Raven’s nest, by knots of grass

And half-inch fissures in the slippery rock

But ill-sustained; and almost (so it seemed)

Suspended by the blast that blew amain,

Shouldering the naked crag; Oh, at that time,

When on the perilous ridge, I hung alone,

With what strange utterance did the loud dry wind

Blow through my ears! The sky seemed not a sky

Of earth, and with what motion moved the clouds!

Registering the ministry of fear more than of beauty, the Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins would echo these lines in one of the “terrible sonnets” of 1885. “Pitched past pitch of grief” in the dark night of his soul, he interiorized Wordsworth’s moment “hung” on the cliff: “O the mind, mind has mountains; cliffs of fall/ Frightful, sheer, no-man fathomed. Hold them cheap/ May who ne’er hung there.” As Hopkins knew, mountain terror rears its head elsewhere in Wordsworth’s accounts of his youthful activities in this first Book of The Prelude. In the famous boat-stealing episode, the boy (whose stealth and guilt echo that of pear-thieving Augustine in the Confessions), is not only surrounded by “mountain-echoes.” As he rows farther from the shore, his changing perspective reveals “a huge peak, black and huge,” which, hitherto hidden below the horizon, now “towered up between me and the stars,” and “strode” after him, “with purpose of its own/ And measured motion.” The memory of this terrifying spectacle—self-created by the rower yet soul-fostering” and sublime in its effect—plunged him into a world of “unknown modes of being,” with no familiar or pleasant shapes, but “huge and mighty Forms” that “moved slowly through the mind/ By day, and were a trouble to my dreams” (1850: I. 356-400).

Sublimity supersedes fear in the crossing of the Simplon Pass in Book VI. Traveling in revolutionary France in the summer of 1790, Wordsworth and a fellow climber, Robert Jones, journeyed to the Alps, the majesty of the mountains further inspiring their revolutionary hopes. The great passage is foreshadowed by a brief but telling description of how they “first/ Beheld the summit of Mont Blanc, and grieved/ To have a soulless image on the eye” (the actual sight of Mont Blanc), which “had usurped upon a living thought/ That never more could be” (VI [1805]453-57). The living thought temporarily “usurped” is Wordsworth’s imagination of the great mountain, its summit more dramatically “Unveiled” in the 1850 version, but its merely Alpine sublimity still inferior to the imaginative power of what Wordsworth’s perceptive admirer Keats would later refer to as “the Wordsworthian or egotistical sublime.”

That usurpation will be repeated, and crucially reversed, seventy lines later. Climbing along the “steep and lofty” Simplon Pass, ascending with eagerness, Wordsworth and his friend lose both their way and their comrades. At length, they encounter a peasant who tells them that they must “descend” to the spot where they first became perplexed, and that “their future course, all plain to sight,/Was downwards.” Reluctant to believe what they so “grieved” to hear, for, as Wordsworth emphasized in 1850, “still we had hopes that pointed to the clouds,” they question the peasant repeatedly, yet every word, augmented by their own feelings, ended in the fact (italicized in 1850) “that we had crossed the Alps” (524).

And here I pause to report another kind of “discovery.” On the very day I thought I had written the final version of this section of my essay, a newly-published book arrived in the mail: English Past and Present, edited by Wolfgang Viereck, consisting of papers selected from an IAUPE conference held in Malta. One essay caught my eye: “Constructions of Identity in Romanticism: The Case of William Wordsworth,” written by a distinguished German Romantic scholar and friend, Christoph Bode. To my initial dismay and eventual delight (an appropriately Wordsworthian trajectory), I discovered that he, too, was examining, with characteristic brilliance, the mountain episodes in The Prelude. Though relieved that we took the same general position, I was humbled by the ingenuity of his nuanced discussion.

For example—to return to and refocus on that crossing of the Alps—Bode persuasively argues that “it is almost as if, contrary to what the preceding lines say, Wordsworth is immensely relieved to know that from now on it is downhill.” While there is surely some disappointment (including Wordsworth’s feeling of having been betrayed by bodily senses and instincts that should have informed him when he was at the high point), compensation, though it came in retrospect, takes the form of a glorious rhetorical outpouring which is, as Bode says, “one of the most impressive apotheoses of the imagination in Wordsworth’s entire oeuvre.” The experience in the Alps was then, 1790. Now, a decade and a half later, its hidden significance is revealed in a visionary experience that apparently came to Wordsworth primarily if not exclusively in the act of writing about that Alpine crossing. Though I prefer the 1850 version, the layering of time requires citation of the 1805 text:

………………..Imagination! Lifting up itself

Before the eye and progress of my Song

Like an unfathered vapour; here that Power,

In all the might of its endowments, came

Athwart me; I was lost as in a cloud,

Halted without an effort to break through.

And now, recovering, to my Soul I say

I recognize thy glory; in such strength

Of usurpation, in such visitings

Of awful promise, when the light of sense

Goes out in flashes, that have shown to us

The invisible world, doth Greatness make abode,

There harbors, whether we be young or old.

Our destiny, our nature, and our home

Is with infinitude, and only there;

With hope it is, hope that can never die,

Effort, and expectation, and desire,

And something evermore about to be. (525-42)

What Wordsworth, that preeminent prophet of human hope, realizes in retrospect is that a man’s reach should exceed his grasp. For Romantics enlisted in the visionary company, the glory of the human spirit consists, not in attaining the attainable but in striving for the infinite, even if our mortal capabilities are necessarily finite. Reversing the previous “usurpation,” in which the physical sight of Mont Blanc imposed upon an imaginative vision, Wordsworth, “recovering,” can say to his more conscious soul: “I recognize thy glory.” It is the glory of that “awful Power” which, through “sad incompetence of human speech” (1850 version), we call “Imagination.” This is the creative Romantic Imagination, whose “strength/ Of usurpation” succeeds and supersedes the mere “light of sense,” extinguished “in flashes” that reveal to us “the invisible world.”

The lines immediately following confirm the political analogy. Once ardently committed to the French Revolution (“Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,/ But to be young was very heaven!”), Wordsworth in effect revokes that delusory dream of a material, external Eden in favor of a paradise within:

The mind beneath such banners militant

Thinks not of spoils or trophies, nor of aught

That may attest its prowess, blest in thoughts

That are their own perfection and reward,

Strong in itself, and in the access of joy

Which hides it like the overflowing Nile. (543-48)

Later readers have often been distressed by Wordsworth’s increasingly orthodox religiosity (traceable in the 1850 version of these lines, where the “mind” becomes “the soul,” and that overflowing “access of joy” a more pious “beatitude”). Some will also deem his personal conversion of politics into a cognitive, imaginative revolution less courageous than a retreat to quietism. Here, it seems powerfully validated by those intuitive “flashes” (recalling the Intimations of Immortality Ode’s “master light of all our seeing”) revealing both the invisible world and a “greatness” that transcends any merely external triumph. The language remains martial, but, as Yeats would later ask in an unpublished lecture titled “Friends of My Youth”: “Why should we honor those that die upon the field of battle? a man may show as reckless a courage in entering into the abyss of himself.” Writing in 1805, at the apogee of the empire of Napoleon, that usurper of the Revolution, who had by then twice exploited the strategic significance of the Simplon Pass (the shortest route between Paris and Milan) by building suspended bridges across the ravine), centripetal Wordsworth is no less dismissive of external battle, its spoils and trophies, and equally insistent on inward strength. Like Paul, Milton, Blake, and Yeats himself, Wordsworth elevates spiritual or imaginative struggle over “corporeal warfare.”

Having recorded the inner reward of mountain vision, the poet returns to the initiating experience. Overcoming the “dull and heavy slackening” that ensued on hearing the peasant’s news, Wordsworth and his friend hastened down a narrow chasm, their pace slowing as they descended. What Wordsworth sees and hears (rocks muttering, crags speaking “as if a voice were in them”) in the Gorge of Gondo is at once natural and epiphanic. The clash of polar opposites is apocalyptically reconciled, natural flux ending in permanent form, tumult in a final peace:

The immeasurable height

Of woods decaying, never to be decayed,

The stationary blasts of waterfalls,

And everywhere along the hollow rent

Winds thwarting winds, bewildered and forlorn,

The torrents shooting from the clear blue sky,

The rocks that muttered close upon our ears,

Black drizzling crags that spake by the way-side

As if a voice were in them, the sick sight

And giddy prospect of the raving stream,

The unfettered clouds, the region of the Heavens,

Tumult and peace, the darkness and the light—

Were all like workings of one mind, the features

Of the same face, blossoms upon one tree,

Characters of the great Apocalypse,

The types and symbols of Eternity,

Of first and last, and midst, and without end. (VI. 556-72)

The Alpha and Omega of Revelation is fused—though, in Wordsworth’s case, with no reference to God—with Adam’s prayer (Paradise Lost V. 153-65) that the things of this world should extol their Creator, “him first, him last, him midst, and without end.” Though the revelation, at last, of the natural sublimity of the mountain landscape is revealed when Wordsworth is descending, we may be reminded of Petrarch, meditating on his ascent of the mountain and seeking his friend’s prayer that his “wandering thoughts” may become “more coherent” and, having been “cast in all directions,…may direct themselves at last to the one, true, certain, and never-ending good.” Both poets are internalizing the external mountain scenery, but while Petrarch’s terms are specifically Christian and moral, Wordsworth’s language, though echoing the Bible and Milton, remains nonsectarian, mysterious, Sublime. There is a striking resemblance (coincidental or a reflection of Coleridge’s Kantian influence on his friend) to Kant’s theory of the sublime, a feeling experienced when, however overwhelmed or even terrified as a merely sensual being, one realizes that, through the power of Reason, “a faculty of the mind surpassing every standard of Sense,” one is able to form an idea of the Infinite. As Bode notes of Wordsworth’s Alpine descent, now that the mountains, with all their “infinite grandeur,” are “identified as the external representation of something internal, they are no longer terrifying, but [in a serious pun] downright uplifting. The landscape does not praise God, it praises Mind,” in its most exalted, or intuitive, form: that of the creative Imagination.

3

Appropriately, inevitably, the final Book of The Prelude gives us, along with Wordsworth’s climactic mountain vision, his re-assertion of the even more sublime power of the creative imagination, that glorious faculty (to quote the final lines of both versions of The Prelude) almost infinitely “more beautiful than the earth” on which “man dwells, above this Frame of things,” in “beauty exalted, as it is itself/ Of substance and of fabric more divine.” Since in this case, and in both versions, the inner meaning of what was seen and heard on the mountain was recognized during the climb rather than retrospectively, and since in this case the 1850 version is rhetorically superior, I will quote the later text.

Accompanied again by his friend Jones and a third companion, the poet ascended at night the highest peak in Wales, “to see the sun/ Rise from the top of Snowdon.” Climbing with “eager pace, and no less eager thoughts,” Wordsworth was in the lead, when suddenly “at my feet the ground brightened,/And with a step or two seemed brighter still.” No time was “given to ask, or learn, the cause;/ For instantly a light upon the turf/ Fell like a flash.” Unlike the inner “flash” of Imagination revealing “the invisible world” in Book VI, this flash of light comes from above. It is not, however, the rising sun, the spectacle that motivated this nocturnal excursion, but the lunar recipient of the sun’s reflected light:

………………..lo! As I looked up,

The Moon hung naked in a firmament

Of azure without cloud, and at my feet

Rested a silent sea of hoary mist. (XIV. 5-6, 35-42)

The vapors project over headlands and promontories, “Into the main Atlantic, that appeared/ To dwindle, and give up his majesty,/Usurped upon as far as sight could reach” (46-50). But the mist does not encroach upon the heavens, dominated by “the full-orbed Moon,/Who, from her solemn elevation, gazed/ Upon the billowy ocean, as it lay/All meek and silent,” except for the noise audible through a rift in the clouds. Through that rift (in lines recalling the Gorge of Gondo, though reversing perspective) “Mounted the roar of waters, torrents, streams/ Innumerable, roaring with one voice!” (50-60). Once reflected upon with “calm thought,” what he describes as “That Vision, given to Spirits of the night,/And three chance human wanderers,” appeared to the climber “the type/ Of a majestic intellect.” As Wordsworth’s language reveals, that emblematic Mind is a secular variation on Milton’s Holy Spirit “brooding” dove-like over the “vast abyss,” making Chaos fruitful (Paradise Lost I. 20-22):

There I beheld the emblem of a Mind

That feeds upon infinity, that broods

Over the dark abyss, intent to hear

Its voices issuing forth to silent light

In one continuous stream; a mind sustained

By recognitions of transcendent power,

In sense conducting to ideal form,

In soul of more than mortal privilege. (70-77)

While the mountain scene is natural, and we mount to vision through the senses, those truly gifted recognize the transcendent power of the mind, its capacity to creatively mold and convert sensory apprehensions of the outward show of innumerable and ever-changing phenomena into ideal and emblematic forms, permanent and unified. The initial project, “to see the sun/ Rise from the top of Snowdon,” is now utterly beside the point. Even the moon, “hung in a firmament/ Of azure without cloud,” beautiful as it is, is secondary not only to its source of light, the sun, but to another power that bathes the world in luminous meaning. This transforming, or “usurping,” power is, as always, that of the human mind in its highest form, “intuitive Reason” (120), by which Wordsworth—like Milton, Coleridge, and Ralph Waldo Emerson—means what Coleridge called the “shaping spirit of Imagination.” For Coleridge and those he influenced, the Romantic Imagination—a faculty at once emotional, cognitive, and spiritual—echoes and alters the epistemological re-orientation announced in the “Transcendental Idealism” section of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason: that “Copernican revolution” in which the shaping mind gives form to the external objects it perceives, subordinating things to thought, just as the sensual is ultimately dominated by the cognitive in Kant’s theory of the Sublime.

Reflecting his own Coleridgean reading of Kant, Emerson ended his seminal text, ironically titled Nature, by asserting “the kingdom of man over nature.” An equally Coleridgean Wordsworth, speaking directly to his friend, writes that, together, they will “instruct” others (in the concluding lines of this epic poem dedicated to Coleridge) “how the mind of Man becomes/ A thousand times more beautiful than the earth/ On which he dwells,” being “In beauty exalted, as it is itself/ Of quality and fabric more divine” (1850: XIV, 450-56). In the Snowdon passage, struggling to depict the reciprocal relationship between the mind and external Nature, Wordsworth falls back on epistemologically slippery or at least paradoxical formulations (“mutual domination,” “interchangeable supremacy”), and an emphasis on the senses and emotion before, inevitably, celebrating the power of the all-illuminating mind:

One function, above all, of such a mind

Had Nature shadowed there, by putting forth,

‘Mid circumstances awful and sublime,

That mutual domination which she loves

To exert upon the face of outward things,

So moulded, joined, abstracted; so endowed

With interchangeable supremacy,

That men least sensitive see, hear, perceive,

And cannot choose but feel. The power which all

Acknowledge when thus moved, which Nature thus

To bodily sense exhibits, is the express

Resemblance of that glorious faculty

That higher minds bear with them as their own. (78-90)

The passage is complex, but what emerges is the supremacy of what Nature merely “shadowed there”—namely, that “glorious faculty,” the creative Imagination, in the exercise of which the highest human minds, at once reflecting and exceeding the orchestrating but limited power of Kant’s pure Reason, resemble Miltonic “angels stopped upon the wing by sound/ Of harmony from heaven’s remotest spheres” (98-99).

.

4

The Prelude has long been recognized as, next to Paradise Lost itself, the greatest poem of its length in English. Excerpts, including the crossing of the Simplon Pass, appeared during Wordsworth’s lifetime, but the poem as a whole became public only after the poet’s death, in 1850. The long poem known to his contemporaries was not his autobiographical epic, but The Excursion (1814), the poem intended to be second in the triadic structure announced in the prefatory poem: “a kind of Prospectus of the design and scope of the whole” of his project, including the culminating epic, to be called The Recluse. This so-called “Prospectus” to The Recluse was of immense importance to Emerson, who reprinted its 107 lines in his anthology, Parnassus, under his own title, “Outline.” Emerson was also impressed by the poem it accompanied, The Excursion, a lesser epic which nevertheless contains several notable mountain visions. In his 1840 essay “Thoughts on Modern Literature,” Emerson remarked that “The Excursion awakened in every lover of nature the right feeling. We saw stars shine, we felt the awe of mountains….” He is recalling those moments in Book I (paralleling the formative personal experiences recounted in the opening Book of The Prelude) where the boy who would become the Wanderer interacted with the natural world. We encounter him, as Emerson remembered, as he “all alone/ Beheld the stars come out above his head” (128-29), and “felt the awe of mountains.” That boy knew his Bible; “But in the mountains did he feel his faith” (223), a feeling of sublimity in which “the least of things/ Seemed infinite; and there his spirit shaped/ Her prospects; nor did he believe,–he saw.”

…………..Such was the Boy—but for the growing Youth

What soul was his, when, from the naked top

Of some bold headland, he beheld the sun

Rise up, and bathe the world in light! He looked—

Ocean and earth, the solid frame of earth

And ocean’s liquid mass, in gladness lay

Beneath him:–far and wide the clouds were touched

And in their silent faces could he read

Unutterable love…his spirit drank

The spectacle: sensation soul, and form,

All melted into him…in them did he live,

And by them did he live; they were his life. (197-210)

At such times, the Wanderer was “Rapt into still communion that transcends/ The imperfect offices of prayer and praise,/ His mind was a thanksgiving to the power/ That made him; it was blessedness and love!” (215-18). It is hardly surprising that the American Transcendentalist, who most famously presents himself rapt in a still communion in which he becomes “a transparent eyeball” (recapturing as well the moment in “Tintern Abbey,” when “we see into the life of things”) should respond so intensely to such a transcendent moment, and even think that “obviously for that passage” the whole of The Excursion “was written.” Emerson had, as any one would, reservations about the didactic stretches of The Excursion (“This will never do,” Francis Jeffrey’s famous Edinburgh Review dismissal of the long-awaited epic, has resonated with more than a few readers). But there were other passages than the one for which the poem was “obviously” written that also haunted Emerson. At certain privileged and precarious moments (he recorded in his journal) the soul “in raptures unites herself to God and Wordsworth truly said, “’Tis the most difficult of tasks to keep/ Heights which the soul is competent to gain’” (Journals and Miscellaneous Notebooks 4:87). Emerson often cited these lines (Excursion IV.139-40), most memorably in his late essay “Inspiration,” where he laments the unpredictability and evanescence of such moments on the “Heights”: “with us” there is “a flash of light, then a long darkness, then a flash again…This insecurity of possession, this quick ebb of power…tantalizes us.”

Emerson was also fascinated by a related moment of “sublimity” in Book II of The Excursion, a vision experienced, as Emerson records in his journal, by “Wordsworth’s Recluse on the mountain” (JMN 8:51). The blinding mountain mist momentarily parts and the Recluse (or Solitary) glimpses “Glory beyond all glory ever seen.” He has a vision of a heavenly city, a natural phenomenon revelatory of the supernatural, an intimation of immortality (II. 827-81). Emerson, along with John Ruskin (Modern Painters, 364), thought this the most sublime of Wordsworth’s mountain visions. But Emerson was also affected by the mountain perspective with which The Excursion ends: a vision of a magnificent sunset seen from a “grassy mountain’s open side,” an “elevated spot” surrounded “by rocks impassable and mountains huge” (IX. 570-612).

All of these Wordsworthian mountain visions were consciously echoed by Emerson, striving to attain an elevated, enlarged, more affirmative perspective, especially at times when he was desperately seeking consolation in distress. Emerson suffered many familial tragedies, among them the premature death in 1836 of his closest brother, Charles. For all his alleged, even notorious “serenity,” Emerson had, five years earlier, intensely mourned the death of his nineteen-year-old wife, Ellen. In the privacy of his journal he confronted “that which passes away & never returns,” almost fearing that “this miserable apathy” will wear off, and that he will resume among his friends “a tranquil countenance.” He may even, stooping again to “little hopes & little fears,”

forget the graveyard. But will thy eye that was closed on Tuesday ever beam again in the fullness of love on me? Shall I ever be able to connect the face of outward nature, the mists of the morn, the star of eve, the flowers, & all poetry, with the heart & life of an enchanting friend. No. There is one birth & one baptism & and one first love and the affections cannot keep their youth any more than men. (JMN 3:226-27)

Retreating to the solitude of the White Mountains, and then sailing to Europe to meet Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Carlyle, Emerson had eventually recovered from that loss. But as he turned from Charles’s grave, he asked with an enigmatic laugh, what there was “worth living for.” Two weeks later, though he could say, “night rests on all sides upon the facts of our being,” he could also add: we “must own, our upper nature lies always in Day” (Letters 2:19-25). But in the immediate aftermath of the devastating loss of his brother, Emerson fell into a despondency relieved, he tells us, by intense reading of Wordsworth: “Tintern Abbey,” the Intimations Ode (his favorite poem), and, again, the speeches of the Wanderer in The Excursion. “Those who have ministered to my highest needs,” he wrote in his journal for May 9, 1836, “are to me what the Wanderer in The Excursion is to the Poet. And Wordsworth’s total value is of this kind.” Echoing the Ode, as he had in insisting that “our upper nature lies always in Day,” he describes men such as Wordsworth, who offer comfort in distress, as possessing “the true light of all our day.” Their “spirit” constitutes “the argument for the spiritual world” (JMN 5:160-61). Writing in mid-May, after ten days of “helpless mourning,” Emerson began, tentatively, to recover. “I find myself slowly….I remember states of mind that perhaps I had long lost before this grief, the native mountains whose tops reappear after we have traversed many a mile of weary region from our home. Them shall I ever revisit?” (JMN 3:77).

Here, in struggling to achieve that “most difficult of tasks,” to “keep” the Wordsworthian “Heights” or mountain tops he knew the soul was capable of gaining, Emerson was recalling, as a despairing William James later would, the mountain visions and hopeful “states of mind” dramatized by Wordsworth in The Prelude, as well as the consolation offered by his stoical yet enraptured visionary, the Wanderer, especially in the fourth and final Books of The Excursion. Comforted and “elevated” by the Wanderer’s urging of the grief-stricken to convert “sorrow” into “delight,” the “palpable oppressions of despair” into the “active Principle” of hope (Excursion IV. 1058-77; IX. 20-26), a grieving Emerson saw the “tops” of his own “native mountains” begin to reappear, to feel an influx of hope, power, and that “glad light” that is, as he says, “the true light of all our day.” In the journal-entry mourning the loss of Ellen, Emerson had feared that he was forever cut off from nature and from life itself, since there is only “one first love and the affections cannot keep their youth.” That imagery is related to his persistent evocation of the “light of all our day.” To quote the lines he repeatedly, almost obsessively, cites or paraphrases from Wordsworth’s great Ode, Emerson is struggling to recover

……………………………….those first affections,

…………………….Those shadowy recollections

…………..Which, be they what they may,

Are yet the fountain light of all our day,

Are yet a master light of all our seeing….(Ode, lines 148-52)

Since the recollection of those “first affections” and the intimations of immortality inherent in that light “Uphold us, cherish, and have power to make/ Our noisy years,” including “all that is at enmity with joy,” seem mere “moments in the being/ Of the eternal Silence: truths that wake/ To perish never,” it is not surprising that, in quoting the lines, Emerson invariably elevated “a master light of all our seeing” to “the master light of all our seeing.” There is one other reason, immediately relevant to the theme of this essay, for my emphasis on the “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.” Since we began with the “light” seen by Columbus on October 11, 1492, and have been emphasizing, beginning with Keats’s discovery-sonnet and Petrarch’s ascent of Mount Ventoux, the imaginative internalization of exploration, it seems worth adding that, for Emerson, Wordsworth’s great Ode was, above all, a momentous act of discovery. The poem was, he insisted, a “new” voyage “through the void,” representing the “high-water mark” the human mind “has reached in this age….No courage has surpassed that” of the Ode’s author, “this finer Columbus” (JMN 14:98). Emerson revisited that journal entry, reinforcing his variation on the imperial theme, a variation resembling Wordsworth’s sublimation of “banners militant” and “trophies” of war in the lines on the crossing of the Simplon Pass. Emerson concludes chapter 17 of English Traits by asserting that Wordsworth’s Ode added “new realms…to the empire of the muse.”

5

An admirer of the Ode, but a less likely reader of The Excursion, was W. B. Yeats, who set himself—as “a duty to posterity,” according to Ezra Pound, staying with him at Stone Cottage at the time—a Herculean task. He told his father in January 1915 that he had “just started to read through the whole seven volumes of Wordsworth in Dowden’s edition. I have finished The Excursion and begun The Prelude.” But the sententious Wanderer was too facilely optimistic for Yeats’s more astringently joyful taste. Locating himself among “the last Romantics,” Yeats never forgot his boyhood image of Byron’s Manfred, poised in solitude above the clouds on the narrow ledge of the mountain glacier: an image visually echoed in Caspar David Friedrich’s mountain-masterpiece, The Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog, painted the year after Byron wrote Manfred. In turn, Yeats associated the Byronic hero with Nietzsche—accurately, since the youthful Nietzsche was no less enraptured than was Yeats by the solitary and autonomous Manfred, destined to become one of the principal prototypes of the Űbermensch. Unsurprisingly, Yeats’s ultimate mountain vision, epitomizing “tragic joy,” emerges under auspices less Wordsworthian than Nietzschean. I conclude with Yeats’s superb late poem, “Lapis Lazuli,” written in 1936—precisely a century after Emerson’s journal entries and six centuries after Petrarch ascended Mount Ventoux. Appropriately enough, the poem was published on the eve of World War II.

Writing, like Wordsworth, at a moment of historical crisis, Yeats is annoyed by those who cannot abide the gaiety of artists creating amid impending catastrophe. To counter their consternation, dismissed as “hysterical,” Yeats presents a panorama of civilizations falling and being rebuilt. In his famous “Ode,” Arthur O’Shaughnessy, noting that, while one age may be dying, another is coming to birth, claimed that poets “Built Ninevah with our sighing,/ And Babel itself with our mirth.” An echoing Yeats asserts that “All things fall and are built again,/ And those that build them again are gay”: visionary artists creating out of an ineradicable joy—Homeric, Shakespearean, Nietzschean—in the face of tragedy. Specifically countering the “hysterical women” of the opening lines, Yeats presents Shakespearean heroines—Ophelia and Cordelia, with the glorious queen of the final act of Antony and Cleopatra in the wings—who “do not break up their lines to weep.” Above all, “Hamlet and Lear are gay;/ Gaiety transfiguring all that dread.” Fusing western heroism with Eastern serenity and a more specifically Nietzschean joy, the poem turns in its final movement to the mountain-shaped lapis lazuli sculpture given to Yeats as a gift, and which, in turn, giving the poet his title, serves as the Yeatsian equivalent of Keats’s Grecian urn. He begins by describing the figures on the stone:

Two Chinamen, behind them a third,

Are carved in lapis lazuli;

Over them a long-legged bird,

A symbol of longevity;

The third, doubtless a serving man,

Carries a musical instrument.

In the “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” Keats’s empathetic imagination peaks in evoking scenes not pictured on the urn. Speculating about the origin of those in the sacrificial procession in the fourth stanza, he asks: “What little town by river or sea-shore,/ Or mountain built with peaceful citadel,” has been “emptied” of its people, now caught forever, frozen in stone and never to return. In a similar leap of imagination (even to the repeated ors), Yeats goes on to transform into natural aspects of an invented mountain scenery what were mere imperfections in the stone (accidents I almost added to some years ago, nearly dropping the piece of lapis while visiting the home of Michael and Grania Yeats):

Every discoloration of the stone;

Every accidental crack or dent,

Seems a water-course or an avalanche,

Or lofty slope where it still snows

Though doubtless plum or cherry-branch

Sweetens the little half-way house

Those Chinamen climb towards….

Adopting, as Keats had, what Wordsworth calls the “usurping” power of that “glorious faculty,” the Imagination, Yeats not only transforms defects in the stone into features of mountain scenery; in describing what is depicted on the sculpture, he creatively imagines the immobile climbers (as frozen in stone as Keats’s urn-figures) having actually attained the gazebo they are depicted climbing “towards”:

………………………………and I

Delight to imagine them seated there;

There, on the mountain and the sky

On all the tragic scene they stare….

Once “there,” they attain, thanks to the imaginative intervention of Yeats, a prospect from which, like Keats’s explorers on Darien, they “stare” out, surveying “all.” One of the two Chinese sages requests music from their companion, who, though “doubtless a serving-man,” is the poem’s musician and resident artist. “Accomplished fingers begin to play,” producing silent music from a carved instrument played by a carved man. Addressing the musical instrument carried by the piper carved on the surface of the Grecian urn, Keats insists that “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard/ Are sweeter; therefore, ye soft pipes, play on.” This “soft” music (just, as it were, beneath the threshold of hearing) is addressed, “Not to the sensual ear,” but, more cherished, “to the spirit.” In both poems, we have an auditory as well as a visual leap of the creative imagination, and an appeal beyond the merely sensual.

The music in “Lapis Lazuli” contributes to the softening of what might have been an austere scene. A few years earlier, in his sonnet “Meru,” Yeats had imagined other mountain visionaries: “Hermits upon Mount Meru or Everest,/ Caverned in night under the drifted snow,” or exposed to dreadful winter storms that “Beat down upon their naked bodies.” While the poet of “Lapis Lazuli” asserts that all things fall and are built again, the Hindu hermits on their sacred mountain, having entered into “the desolation of reality,” know only that “day brings round the night, that before dawn,” man’s “glory and his monuments are gone.” In “Lapis Lazuli,” where the falling “snow,” far from battering naked bodies, seems indistinguishable from cherry blossoms, the tragic vision ends in tragic affirmation.

The melodies may be “mournful,” but, again balancing East with West, the final movement also registers what Yeats perceptively identified as Nietzsche’s “curious astringent joy.” There is even a conscious echo of the gravity-defying gaya scienza of Nietzsche’s prophet, Zarathustra, who insists (I.7, “On Reading and Writing”) that “he who climbs the highest mountains laughs at all tragic plays and tragic seriousness.” Though Yeats didn’t know it, Zarathustra was echoing Wordsworth’s disciple Emerson, in turn a formative influence on the life and work of Nietzsche, who considered him the finest, and most tonic, thinker of the age. Since Emerson himself had referred to the “gay science,” it seems only appropriate that the original epigraph to Nietzsche’s The Gay Science was taken from Emerson. In a splendid passage of Twilight of the Idols (IX.13), contrasting Emerson with his friend Carlyle, Nietzsche pronounces the former “Much more enlightened, more roving, more manifold, subtler than Carlyle; above all, happier.” Illuminating rather than caricaturing Emersonian “optimism,” Nietzsche associates his mentor with his own Zarathustrian dismissal of the spirit of gravity: “Emerson has that gracious and clever cheerfulness which discourages all seriousness.” Here, at last, are the crucial concluding lines of “Lapis Lazuli,” but they require, as context, re-quotation of the whole of the exquisite final movement:

Every discoloration of the stone;

Every accidental crack or dent,

Seems a water-course or an avalanche,

Or lofty slope where it still snows

Though doubtless plum or cherry-branch

Sweetens the little half-way house

Those Chinamen climb towards, and I

Delight to imagine them seated there;

There, on the mountain and the sky,

On all the tragic scene they stare.

One asks for mournful melodies;

Accomplished fingers begin to play.

Their eyes mid many wrinkles, their eyes,

Their ancient glittering eyes are gay.

The fact that the perspective is not quite sub specie aeternitatis, that the “little half-way house” is situated at the midpoint rather than on the summit, makes this a human rather than divine vision. But that in itself also makes it the very epitome of a modern mountain vision, an affirmation, registered in full awareness of “all the tragic scene,” in which the eyes, and the Ayes, have it. The eyes of Yeats’s Rembrandt-like Chinamen, wreathed in the wrinkles of mutability yet still glittering with tragic joy, recall another Wordsworthian “flash”—the “flash” that breaks from “the sable orbs” of the “yet-vivid eyes” of the decrepit but enduring old leech-gatherer in “Resolution and Independence,” one of Yeats’s favorite Wordsworth poems. Those “ancient glittering eyes” evoke as well the famous “glittering eye” of the Ancient Mariner of Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Appropriately enough, Coleridge was the friend to whom Wordsworth dedicated The Prelude, that epic exceeding even the passages of The Excursion that haunted Emerson as the definitive celebration of the sublime glory of mountain vision.

~

In conclusion: the thematically crucial point is that, for all the high Romantics, early and late, what makes these mountain visions, actual or carved in lapis, truly sublime is that their sensuous, external glory is enhanced—indeed, usurped—by an even greater glory, one “to be found,” as Petrarch said, “only within”: namely, the transforming power of the human imagination. Emphasized in the finales of Emerson’s Nature, Wordsworth’s Prelude, and (as we’ll see in a moment) Keats’s “Ode to Psyche,” that priority is definitively established in the poem in which (as Emerson recognized in re-titling it “Outline”) Wordsworth laid out his entire canonical project. In the “Prospectus” to The Recluse, Wordsworth announces (lines 28-41) that he intends to surpass his master Milton by locating the arena of action in neither the supernatural nor the natural worlds, but within the human mind. Wordsworth is still thinking in terms of mountain gorges and mountain peaks; but, sinking “deep” and ascending “aloft” psychologically rather than physically, he will “pass” by heaven and hell and all other external terrors “unalarmed,” for nothing

………..can breed such fear and awe

As fall upon us when we look

Into our Minds, into the Mind of Man,

My haunt, and the main region of my song.

Fittingly for an admirer of Wordsworth, when John Keats, echoing these lines from the “Prospectus” in the final stanza of the “Ode to Psyche,” declares that he will be Psyche’s solitary “priest, and build a fane/ In some untrodden region of my mind,” he surrounds the sanctuary in that interiorized mental landscape with the “branched thoughts” of “dark-clustered trees” that “Fledge the wild-ridged mountains steep by steep.”

In context, this oracular landscape is necessarily Greek, which may remind us that in the first of his two break-through poems (the second is this Ode), the young discoverer of the greatest of Greek epic poets imagined, as the climactic analogue of his experience on first looking into Chapman’s Homer, the eagle-eyed discoverer of the Pacific staring out, “Silent, upon a peak in Darien.” Keats’s poetic temple dedicated to the one neglected goddess in Greek mythology is the autonomous creation of a young poet, as he insists earlier in the Ode, “by my own eyes inspired.” Necessarily, that temple is to be found only within, in “the Mind of Man”: Wordsworth’s “haunt,” and the “main region” of his poetry. When Keats locates his shrine to Psyche in a secluded “region of my mind,” the echo reconfirms that it is a mental edifice, a dome built in air. And yet, in the poet’s imagination—a creative imagination as delighted and fecund as Yeats’s in “Lapis Lazuli”—that shrine is surrounded by “wild-ridged mountains steep by steep.” In short, no matter how interiorized the “region,” it retains, perhaps inevitably given Keats’s reverence of Wordsworth, the vestiges of yet another of his precursor’s imaginatively-transfigured mountain visions.*

————

*A sad postscript. Keats thought The Excursion, including the “Prospectus” that introduced it, one of the few things “to be wondered at in this age,” and we know, from his friend Benjamin Hayden, that the passage he preferred “to all others” was the beautiful evocation of the world of Greek mythology in Book IV, reanimating the sun-god Apollo with his “blazing chariot” and ravishing lute, and the “beaming” moon-goddess, Diana, moving “across the lawn and through the darksome groves” (850-64). Yet when Keats, urged by Hayden, read aloud to Wordsworth his early “Hymn to Pan,” the older poet famously if somewhat ambiguously responded: “a very pretty piece of paganism,” apparently condemning with faint praise. Would Keats’s hero have thought the same of the far superior “Ode to Psyche”? Though one fervently hopes not, he may have, given his hardening Christian orthodoxy by then, and what Keats perceptively and, with equal ambiguity, designated “the Wordsworthian or egotistical sublime.” The “Mind of Man” that was the “main region” of his song was, after all, first and foremost the “mind”—of William Wordsworth.

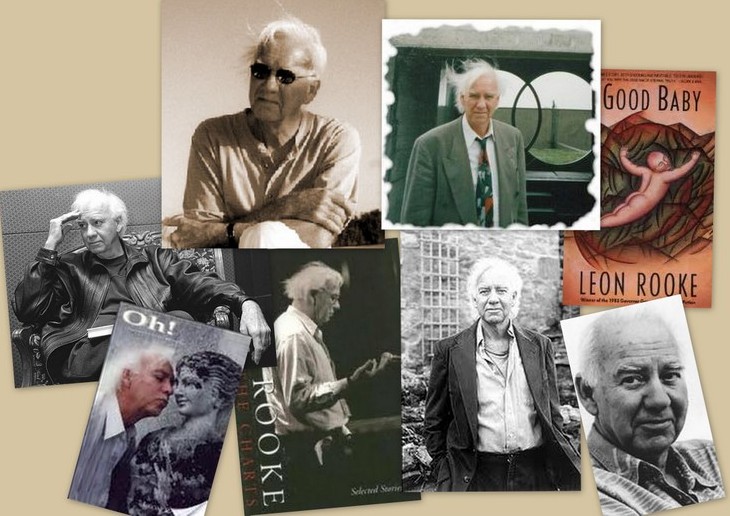

—Patrick J. Keane

—————————————————–

Patrick J. Keane is Professor Emeritus of Le Moyne College. Though he has written on a wide range of topics, his areas of special interest have been 19th and 20th-century poetry in the Romantic tradition; Irish literature and history; the interactions of literature with philosophic, religious, and political thinking; the impact of Nietzsche on certain 20th century writers; and, most recently, Transatlantic studies, exploring the influence of German Idealist philosophy and British Romanticism on American writers. His books include William Butler Yeats: Contemporary Studies in Literature (1973), A Wild Civility: Interactions in the Poetry and Thought of Robert Graves (1980), Yeats’s Interactions with Tradition (1987), Terrible Beauty: Yeats, Joyce, Ireland and the Myth of the Devouring Female (1988), Coleridge’s Submerged Politics (1994), Emerson, Romanticism, and Intuitive Reason: The Transatlantic “Light of All Our Day” (2003), and Emily Dickinson’s Approving God: Divine Design and the Problem of Suffering (2007).