Mangalia Beach, 1930 by Nicolae Tonitza, via Wikiart.

Mangalia Beach, 1930 by Nicolae Tonitza, via Wikiart.

x

I realize, all of a sudden, that my title sounds like the name of a rehab facility in Arizona, a place where “happiness” is very rare indeed and where the “shores” are notional ones, at best. I am quite certain that Baudelaire was not thinking of such a place, as he conjured up a luminous vision of utopia in the first quatrain of his sonnet, “Exotic Perfume”:

When, with both my eyes closed, on a hot autumn night,

I inhale the fragrance of your warm breast

I see happy shores spread out before me,

On which shines a dazzling and monotonous sun.

He was envisioning a place far from the gray realities and dismal vexations of mid-nineteenth-century Paris, a place free from the constraints of the here and the now, somewhere strikingly distinct from the sites we inhabit in our daily life, a place of “order and beauty / Luxury, peace and pleasure,” as he puts it in his “Invitation to the Voyage.” That vision is inspired (and I use that word in its fullest sense) by a lover’s scent. But it is constructed in the poetic imagination, corresponding to a set of ideals clearly impossible in ordinary, quotidian existence. The site toward which Baudelaire points is a distant one and a different one, a place both foreign and unusual—in a word, an exotic place.

It is not uncommon to find evocations of such places in French literature before Baudelaire; yet he explored the idea of the exotic so insistently and programmatically that it became, under his pen, a recognizable, codified literary topos. So much so that it is difficult to speak about any sort of literary exoticism in France without bringing Baudelaire into the conversation—even when it is a question of literary gestures in our own time. For while controversies about what constitutes the “exotic” and what attitudes one ought to adopt with regard to it have undoubtedly evolved a great deal since Baudelaire’s time, the notion itself remains a highly charged one in contemporary French culture, and a sure trigger for polemics of various ilks.

Most recently and notoriously, the idea of the exotic may be seen to subtend debates about the relationship of “metropolitan” French literature (that is, writing produced in France) and “francophone” literature (texts written in French outside of Metropolitan France—in Africa, for instance, or in Quebec, or Haiti). A manifesto signed by forty-four writers which appeared in Le Monde in March of 2007, under the title “Toward a ‘World Literature’ in French,” calls for nothing less than the abolition of the distinction I have just mentioned, proclaiming “[t]he end, then, of ‘francophone’ literature, and the birth of a world literature in French” (56). The manifesto justifies its brief for “World Literature” with considerable vigor:

“World literature” because literatures in French around the world today are demonstrably multiple, diverse, forming a vast ensemble, the ramifications of which link together several continents. But “world literature” also because all around us these literatures depict the world that is emerging in front of us, and by doing so recover, after several decades, from what was “forbidden in fiction” what has always been the province of artists, novelists, creators: the task of giving a voice and a visage to the global unknown—and to the unknown in us (56).

A crucial dimension of the manifesto’s argument hinges precisely on the notion of the exotic, and on the marginalization that such a designation entails: “How many writers in the French language, themselves caught between two or more cultures, mulled this strange disparity that relegated them to the margins, themselves ‘francophones,’ an exotic hybrid barely tolerated?” (55). For that marginalization effect is clearly the other face of the notion: if the exotic evokes “Luxury, peace and pleasure,” it also, through that very otherness, points to something far outside a given speaker’s community of experience.

In that perspective, the exotic and terms closely related to it continue to animate discussions in France, discussions that range far beyond purely “literary” spheres, discussions that color much broader cultural and political discourse. I am writing, right now, a couple of months after the Islamic State attacks in Paris on November 13, 2015, and I can testify that a significant proportion of political debate since that event is grounded in the way that the French (and I mean “French” of many different stripes) conceive of the other, whether that other be person, or place, or both at once. In all of that extremely complex and at times very painful debate, one thing is abundantly clear: we are, all of us, very attached to that idea of the other, and very reluctant to abandon it—even when it proves to engender more problems than it serves to resolve. As Sander Gilman puts it in his study of alterity, Inscribing the Other, “Stereotypes arise when the integration of self is threatened. They are therefore part of our manner of dealing with the instabilities of our perception of the world. This is not to say that they are positive, only that they are necessary. We can and must make the distinction between pathological stereotyping and the stereotyping we all need to do to preserve our illusion of control over the self and the world” (13).

Charles Baudelaire 1844 by Emile Deroy, via Wikimedia Commons.

Charles Baudelaire 1844 by Emile Deroy, via Wikimedia Commons.

x

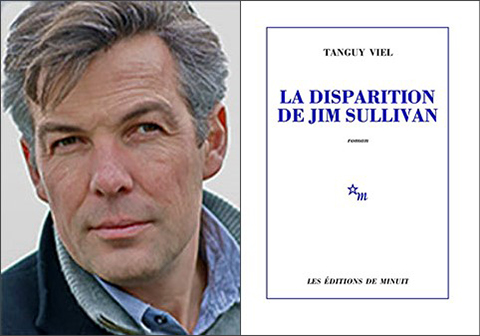

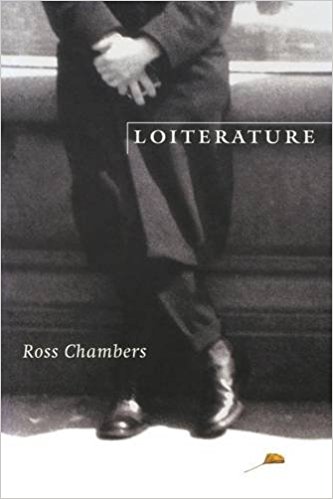

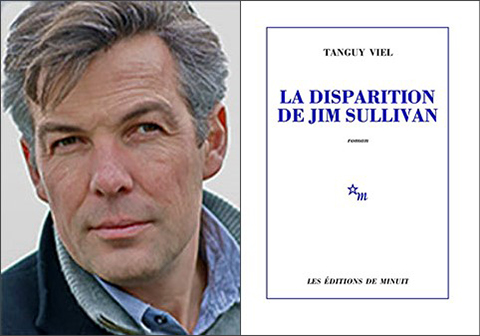

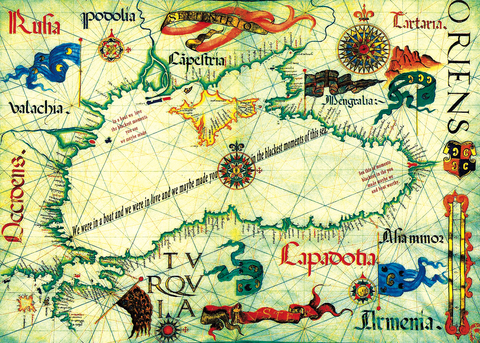

Having noted the breadth of sway that the exotic enjoys in the French imagination, I would like now to turn to happier shores than those of massacre and the reaction that it provokes. I would like briefly to examine a few recent French novels that are situated in part or in their entirety in the United States. These are texts wherein the notion of “America” is deployed as a radical other with regard to metropolitan French culture, and which play with the idea of the exotic in a very interesting manner. The first example I shall adduce (one where the phenomenon that interests me is both most massive and obvious) is Tanguy Viel’s La Disparition de Jim Sullivan (2013). The second word in Viel’s title is usually rendered into English as “disappearance”; but in its euphemistic usage it can also mean “death,” and Viel plays productively on that semantic ambiguity throughout his novel. It is not the only ambiguity that he exploits. For his narrator, like Viel himself, is a French novelist—and he is moreover working on a book entitled La Disparition de Jim Sullivan. Over the last few years, he has become convinced that the only way to achieve truly international literary success is to write an “American” novel:

Americans have an unfair advantage over us: even when they situate the action in Kentucky, among chicken farms and cornfields, they manage to write an international novel.…They manage to write novels that people buy in Paris, as well as in New York. …The day that that became clear to me, I took a map of America and hung it on the wall of my study, and I told myself that the action of my next book, all of it, would be located over there, in the United States. (10-11, my translation, as elsewhere unless otherwise noted)

With considerable energy and admirable diligence, he sets out to write such a novel, exploiting all of the commonplaces that he has identified in the genre. In the first instance, he takes care to strew American proper names throughout his text very liberally indeed. It is a technique that is certain to pay dividends, particularly when one recalls Roland Barthes’s characterization of the proper name as “the prince of signifiers” (“Analyse” 34). Thus, characters’ names are quintessentially American ones: “Dwayne,” “Susan,” “Tim,” “Dorothy,” “Jim,” “Donald,” “Moll,” “Joyce,” “Lee,” “Alex,” “Milly,” “Becky,” “Ralph,” and so forth. That impression of authenticity is heightened by the fact that Viel causes his French novelist to use first names rather than last whenever possible—Americans are renowned for the casual ways they address others, after all. The toponyms are just as familiar as the anthroponyms, moreover: “Montana,” “Kentucky,” “Detroit,” “Michigan,” “New York,” “Los Angeles,” “Ann Arbor,” “Chicago,” “Rochester,” “Sterling Heights,” “Baltimore.” But it is undoubtedly in the names of automobiles where that technique gets its most mileage, for the automobile, as everyone knows, reigns supreme in American consumerist culture: “Cadillac,” “Pontiac,” “Ford,” “Dodge,” Buick,” “GMC,” “Chrysler,” “Mercury,” “Thunderbird.” It sounds like a poem, doesn’t it?—or a prayer.

The behavior of the novelist’s characters is just as convincingly American as their names. They are always driving their cars, for one thing, with “a bottle of whisky on the passenger seat” (16), cigarette butts overflowing the ashtray, a copy of Thoreau’s Walden and a hockey stick lurking in the trunk. Prominent among those characters is a university professor, because Viel’s novelist has noted that “in American novels, one of the characters is always a university professor” (19), a figure so innately beguiling as to captivate the attention of even the most jaded reader. Adultery is everywhere practiced here, fueled undoubtedly by all that whiskey, all those cigarettes, all that driving around. Violence abounds, too, as indeed it must, because Americans are famously inclined to explode into violence one after the other, like firecrackers at a Fourth of July celebration.

Despite all of his laudable efforts at verisimilitude, however, Viel’s novelist remains curiously removed from his “America.” He confesses that he has never actually had the opportunity to visit the United States, and that his information (though abundant) is secondhand, deriving in the main from two sources: American novels and the Internet. The former serve him well enough, I think; but the latter, granted its tendency to flatten and homogenize human experience, sometimes leads him into infelicity and outright error. Much of the action in his novel takes place in Detroit, but everything he knows about that city comes from the Internet, and most of what he has learned is anecdotal and trivial: “In Detroit, according to what I’ve read on the Internet, people can see up to 3200 windows in one glance” (11). He can be excused, perhaps, for spelling “mother fucker” as two words rather than one (34); but his allusion to “lion hunting in the Colorado mountains” (137) will inevitably raise eyebrows. He remains, of course, French; and the gaze that he casts upon America is necessarily a French one, filtered through French culture, ideology, and myth. Moreover, he is demonstrably writing for a French public. “For us here in France,” he remarks for instance, “it seems odd to include an ice hockey team in a novel” (49-50), clearly identifying his narratees as French, and wagering simultaneously on the familiarity of “Frenchness” and the alterity of “Americanness.”

The wager that Tanguy Viel himself stakes is, I believe, a bit different; and the game he is playing is patently a more sophisticated one. Where his novelist is utterly candid (and indeed naive) in his reading of America and its culture, Viel is far more sly, taking an ironic stance both with regard to his narrator and with regard to “America.” Let us remember that irony is always a question of distance, whether literal or figural, and allow me to remark that the notion of distance massively informs both the narrator’s novel and Viel’s own. Yet it is clear that those books are not one and the same, despite the fact that their titles are identical. To the contrary, the distance separating them looms ever larger as the novel—Viel’s novel, let’s be clear—progresses. If that consideration were not perfectly obvious, Viel takes care to underscore it in the closing pages of his novel, causing his narrator to remark:

I didn’t stress it too much in my novel, because I didn’t want to make it a political thriller, with complicated intrigues involving both fictional characters and real people, like American writers often do, it’s true. After all, even if I looked toward America throughout my work on this project, I nonetheless remain a French writer. And we French do not make a habit of mixing real people with fictional characters. That is why I didn’t mention the name of Barack Obama in my novel. (120)

That final pronouncement reads like a Zen kōan, or a paradox of Zeno, until one remembers that this (fictional) novelist is not Tanguy Viel; that the embedded novel is not the frame novel; that, in a word, no gesture of metalepsis has been accomplished here, in spite of any appearance to the contrary, and notwithstanding the pull of our own readerly desire.

With considerable resourcefulness and subtlety, Tanguy Viel exploits that readerly desire in order to keep us significantly (and agreeably) off balance. At some moments, he encourages us to plunge headfirst into the fictional world, abandoning our skepticism and our rationality. At other moments, he obliges us to step back from the fable and recognize things for what they are. Insofar as the representation of America is concerned, his game is likewise double. He puts the mythology of America to use in very canny ways, both frankly (through his very literalist narrator) and ironically (through the distance he constructs between his narrator and himself). Turn and turn about, he plays upon the familiar and the exotic—and, most crucially perhaps, on the familiarity of the exotic. One might say that it is always a question of “America” in this novel, rather than of America. And one might argue, too, that it is a book perfectly suited to “American” readers, whatever happy shores they might call their own.

x

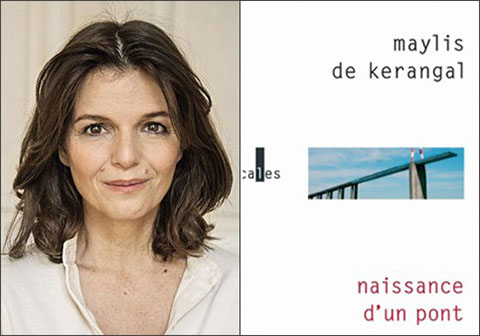

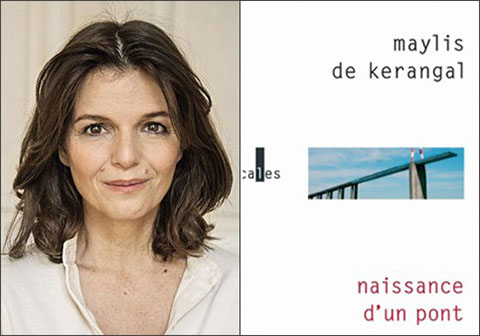

Shores, happy or otherwise, are often at issue in Maylis de Kerangal’s Naissance d’un pont (Birth of a bridge, 2010), which tells the story of the construction of an immense bridge spanning a river, just inland from the coast of California. Like Viel, Kerangal gives place of privilege to onomastics, entrusting proper names with an important dimension of her “American” strategy. People’s names here are about what one might expect: “Katherine,” and “John,” and “Ralph,” certainly, but also that most categorical of American names, “Duane” (here spelled with a u rather than a w). Recognizable figures from the real world flit in and out of the novel, in cameo appearances, among them Sarah Jessica Parker and Larry King. Brand names confirm that the action of the novel takes place in a fundamentally commercial world: KMart, Safeway, Trader Joe’s, Wallgreen [sic], McDonald’s. Chevrolets and Dodges duel on the highways, providing delicious moments of verisimilitude: “It’s a late-model Viper on 22-inch rims, 500 horsepower, a monster worth forty-five thousand dollars” (42). But Kerangal’s onomastic pièce de résistance is undoubtedly the name she chooses for the city where the bridge will be built, “Coca.” She glosses it helpfully for us shortly after enunciating it, mentioning that it shares its name with a famous brand of soda (29). For “Coca” is the French for “Coke,” as any five-year-old in France could testify; and what is more indisputably American than Coke? It represents in some sense the summit of American commercialism, a product known and savored worldwide. In a similar light—and I’m speaking here reductively, of course, relying on cultural commonplace—California represents for many people the apotheosis of American culture, the site where the various currents composing that culture flow in unabated spate.

Yet that is only one of the connotational fields onto which the name “Coca” opens. The other is a shade darker in tone, and the word “cocaine” hovers in its center. The fact that Kerangal has that in mind is confirmed by several references in the text, more subtle but no less sure than the ones pointing to Coca-Cola. Early on, for instance, Kerangal mentions the public buses serving Coca, suggesting that they are dangerous means of transport, “operated by bug-eyed bus drivers: lack of sleep, coke” (29). On several other occasions, she suggests that deep corruption lurks behind Coca’s shiny new facade: “Coca! Coca! Coca! The Brand New City! A danger zone where febrile businessmen rub shoulders with dealers of all kinds, cunning teens, opioid-addicted dandies, loan sharks both male and female, night-blind girls, and bewigged assassins” (169). Contrary to what its Babbitts would have us believe, Coca is “a rotten hole” (72), a place “arising ex nihilo from the New World” (185).

Yet it is perhaps inaccurate to imagine that Coca surges up out of nowhere, perhaps more useful to think of it as emanating from a deep reserve of mythology, one devolving upon “the measureless breadth of the landscape, an unmanageable immensity” (46) and “an enormous desire” (67), a golden place in the Golden State. For desire is at the heart of Coca. Workers flock there from all over, “among whom are people from Detroit, chased out of that city by the closing of the automobile factories” (97) Kerangal notes, reminding us that the American economy has suffered in recent years. Those workers, she argues, are simple folk, “people averse to conversation, serious and dedicated laborers for whom distractions like bowling, beer, and sex would not suffice for long” (101). More than anything else, they are impelled by mythology: “poor people looking to better themselves, dreamers lost in the clutches of the myth of the West, the obstinate myth that consumes them” (189).

The vision of America that Kerangal proposes is thus significantly vexed. On the one hand, it is a place where community milestones are celebrated by “ceremonial releases of doves, cheerleaders, jugglers, traditional Indian dances, police parades, and distribution of free t-shirts” (329). On the other hand, it is a place where local prostitutes “swallow speedballs: coke + bicarbonate of soda” (134). Let us forgive the inaccuracy of the recipe furnished, and focus instead on the brutality of the image, and the way it contrasts with that of the municipal festivities. And let us remember that the very notion of contrast itself is an essential component of the mythology in which “America” is wrapped:

It is the land of making-do and the smalltime job, of accommodations and fiddles, of all the little strategies of survival that sharpen one’s wits, the land of little vegetable gardens, fertile and overgrown, the land of hammocks swung up in damp cabins, of plasma TVs right off the shelf and fridges filled with beer, of mobile homes where depressed Indians with penetrating gazes try to sleep, of prefabricated, slapped-up houses that won’t make it through the winter, their floors warping and their wiring melting as soon as the portable heating units are plugged in, their pipes freezing right under the siding. It’s the place on the other side of the water, the edge of the city and the verge of the forest, it’s the place right on the margin. (191-192)

In short, Maylis de Kerangal’s “America” is a liminal place, one that is neither fully “inside” nor “outside,” but which insistently questions both of those sites in an oppositional manner, and through a discourse of alterity. It’s no utopia, that’s for certain. But I think nonetheless that Baudelaire would have no trouble recognizing it as somewhere demonstrably animated by the spirit of the other, a place very efficiently conceived to make the reader of this novel reflect usefully upon that other—and perhaps more crucially still, upon the place that he or she calls “home.”

x

Representations of America are not lacking in Christine Montalbetti’s writings. Her novel Western (2005) takes place in a rough-and-ready frontier town called “Transition City,” and it plays upon a venerable set of traditions inherited from Bret Harte and Zane Grey, John Ford and Sergio Leone. Journée américaine (American day, 2009) returns to the American West, but in present time, following a man as he makes his way across the plains of Oklahoma to the mountains of Colorado. In Plus rien que les vagues et le vent (Nothing but the waves and the wind, 2014), Montalbetti goes still further west, to the Oregon Coast. There, everyone has a story to tell: “Colter,” “Harry Dean,” “McCain,” “Shannon,” “Wendy,” “Moses B. Reed,” “Mary,” “Perry,” “Rick,” “Tim Doyle,” each of them has a past with a different tale. Yet those differences may be largely anecdotal, because every one of these individuals is scarred by the past, and the tales they tell testify to that damage in fundamentally similar ways. They have all somehow washed up in Cannon Beach, “the furthest edge of America” (271), like driftwood. Harry Dean works there as a farmer; Wendy is a waitress; Moses owns a bar called “Ulysses’ Return”; Tim runs a souvenir shop; Mary works in the grocery store; and so forth. Their lives intersect frequently in this small town, often in the bar in the evening, and that is mostly where we hear their stories, thanks to the narrator. He is a curious bird, the only anonymous character in the novel. He is exceptional in other ways, too, for we know very little about his past, merely that he is French—”the fucking Frenchy,” as he calls himself on one occasion (228), adopting the epithet that has been used by some of the more xenophobic citizens of Cannon Beach to identify him—and that he has come up the coast from Long Beach, through Portland. “It begins like a road story, when you think about it” (15), he remarks.

I got here on a rainy day, in a rented Ford (a white Crown Victoria, with rear-wheel drive).

The car, with its automatic transmission, ate up the road, almost without any effort on my part. I gazed at the rain beading up on the windshield, then being wiped off, then once again beading up like on the very first day, then again being massacred under the rubber blades of the windshield wipers, pressing against the glass. (16)

Road stories are of course typically American narrative forms. America did not invent the road story, to be sure, no more than Baudelaire invented the idea of the exotic. But America indisputably appropriated the form, injected it with a massive dose of specifically American mythology, exploited it to a rare degree, and exported it so successfully that it can now can be said to bear an American stamp—at least in its most recognizable shape, where the mode of transportation is always four-wheeled, the road is always broad, and the direction is always westerly.

The narrator’s road story is not the only one in this novel, moreover, because all of the characters have been involved in their own road stories, before each of those stories crested and broke upon Cannon Beach. Still other narratives circulate liberally in this fictional world. The narrator reads and rereads Lewis and Clark’s Journals, for instance, in a two-volume edition belonging to Perry. He does not seem to recognize that he is holding in his hands one of America’s foundational road stories, but that fact is surely not lost on the reader of Montalbetti’s novel. One night in the bar, the talk turns to the Odyssey—yet another road story, but this time far more venerable—and Harry Dean knows enough of it to assure the others that it is a tale that ends in blood. That is just one effect among many others suggesting that this story will likewise end in blood. Catastrophe looms from the beginning of the novel. Pressure builds and will seek release, in an eruption as inevitable as that of Mount St. Helens, which the folks in Cannon Beach remember all too well. Reflecting on the events of the recent past in his motel room, gazing out at the sea day after day, the narrator comes to understand that he himself is involved in a story, though the question of what role he may play therein—witness or actor, victim or hero—is well beyond his ken. He tells his tale in an engaging, complaisant, dilatory manner, one that seems unconcerned until we realize that he is deferring an event which is far more painful to tell, a very violent event through which he is significantly transformed.

One might suggest that, more than anything else, the narrator’s transformation is a question of naturalization—one that involves, in the first instance, his body:

Since I have been holed up and idle in this motel room on the edge of America, existing on local fare (pizza and hamburgers that I have delivered), my body has become American.

That was what I was seeking, undoubtedly, that metamorphosis.

I have to say, too, that with all of this space surrounding a person, space that is not merely an idea, but which is also an idea, with the thought of thousands and thousands of square kilometers under immense skies, one can understand, in so vast a dominion, that there should be so many people who wish to be fat. In order to occupy a bit more space. Seeking a more acceptable ratio with the territory.

To adapt their body to the dimensions of the landscape. (278)

Curiously, the metamorphosis that the narrator undergoes has the effect of erasing his former story in favor of a story to come, or a story yet to be written:

The man that I am now, this fat man, doesn’t have a story yet.

His beginning can be traced back to the day that he rented the white Ford and left Long Beach, California, where he was just passing through, having spent a moment, you’ll remember, watching the pelicans feeding so voraciously. The day that he got on the road and started driving, obliviously, toward his shape to come. When he got into the car, when he stopped at the Blueberry Inn, when he went into the Waves Motel for the first time, he didn’t look like he does now; but that appearance was already in gestation. (280)

It is a matter of catastrophe, after all, one that is far more local and personal than the eruption of Mount St. Helens—but perhaps no less telluric. Importantly, it can be described as a certified “American” catastrophe, one whose principal agency can be located in the way that “Americans” tend to identify themselves in distinction to a variety of others. Though it should be noted that the narrator refuses to recognize such agency. “To my way of thinking,” he remarks, all of that is the ocean’s fault” (86). And in a sense, maybe he’s right, because the ocean (like narrative itself) involves forces that are irresistible, in which even the strongest of swimmers may founder; and once you submerge yourself in it (again like narrative), you are necessarily a part of it, wherever else you may wish to be.

x

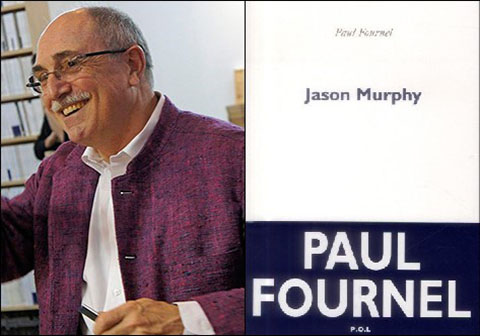

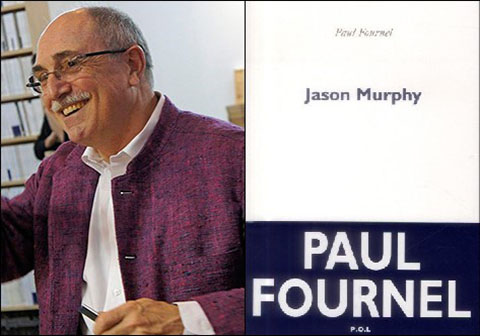

Paul Fournel locates most of the action of Jason Murphy (2013) in France; but his characters direct their gaze across the Atlantic, indeed clear across the continent, once again to the very edge of America. To San Francisco more specifically, and to a cultural moment when the poets of the Beat Generation were just beginning to put right-thinking American mores so dramatically into question. One of those poets interests those characters particularly, a certain “Jason Murphy,” who may have written a novel on a long, continuous scroll well before Jack Kerouac used that technique to write On the Road. The scroll seems to occupy much more space in the characters’ imaginations than the man who wrote it, and who may or may not have survived the glory years of the 1950s and 1960s. People invest their desire in that artifact for different reasons: a publisher because of the sales windfall it would ensure; a graduate student because of what it would represent for her dissertation; a professor of literature mindful of his scholarly reputation; and so forth. As all of them strain toward that object of desire, a kind of Grail Quest emerges; but it is one fraught with ironies of various sorts, and one that is very unlikely to provide salvation for anyone—least of all for Jason Murphy.

Once again, proper names color the text of this novel, and orient the reader’s horizon of expectation in certain ways. Fournel borrows many of those names from contemporary American literature: Gregory Corso, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, William Carlos Williams, Sylvia Plath, Carson McCullers, Willa Cather, Ernest Hemingway, Raymond Carver, Patricia Highsmith, Harry Mathews, Kenneth Patchen, Tom Wolfe. Other familiar cultural figures, from Johnny Cash to Joe DiMaggio and Marilyn Monroe to Jerry Garcia, are name-checked here. On the toponym side of things, Fournel points us toward San Francisco (where he directed the Alliance Française between 1996 and 2000, and which he consequently knows well). Each of the sites that he evokes—Golden Gate Park, Haight Street, the Panhandle, Polk Street, North Beach, the Tenderloin, Berkeley, the Castro, the Mission, Union Square, for example—is recognizable to anyone reasonably familiar with San Francisco. Even someone French (for it must be recalled that he is writing in French, for French readers), because the city of San Francisco occupies a great deal of space in the French cultural imagination, and French tourists abound there. It is perched, after all, smack on the western edge of the American continent, the place where Manifest Destiny sends us, the place where the American Dream (as a European conceives it) reaches its ultimate expression.

It is legitimate to wonder, in view of references to so many real people and places, why Fournel chose to organize his novel around an imaginary author like “Jason Murphy.” Clearly, he has anticipated that question, for when her advisor asks the graduate student why she has chosen to write on Murphy, rather than on Kerouac or Ginsberg, she replies, “Everyone studies those two, they’ve been worked over again and again. People know a lot about them. Murphy is more secret, less well known, a bit on the margins” (39). There is certainly no arguing with that. Yet another reason may be bound up in the fact that people don’t quite know what to make of Murphy’s writing, not even knowing for sure if he’s a “good” writer or a “bad” writer. That is a question the graduate student must grapple with, as she reads and rereads Murphy, while at the same time reading the work of the few critics who have turned their attention to him, including “Donald Allen in New American Poetry 45.60 and The Life and Lives of Jason Murphy by Warren Motte, which she knew by heart” (71).

We can forgive her if from time to time she daydreams about other, more manageable research projects. “Her thoughts turned to Hemingway. A Moveable Feast. Montparnasse is three Metro stations from here. That could have been a great dissertation topic. ‘Paris in the American Imagination: Ernest Hemingway, the Model of the Rich Poor Man.’ 200 pages tossed together in three months, with all of the backdrops right next door” (53). The project that she envisions stands in a pleasingly ironic relation to Fournel’s novel, of course, and it comments upon the latter with some pungency. Because one of the things that Fournel puts on offer in this book is an image of San Francisco as the French imagination constructs it. And by extension, insofar as San Francisco exemplifies certain important features of a broader American ideal, he invites his reader to ponder a defining moment in American cultural history, when “America” began to come to terms with the American Dream as a dream. Hunter S. Thompson points straight at that moment in his Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas:

San Francisco in the middle sixties was a very special time and place to be a part of.…There was madness in any direction, at any hour.…You could strike sparks anywhere. There was a fantastic universal sense that whatever we were doing was right, that we were winning.…We had all the momentum; we were riding the crest of a high and beautiful wave.…So now, less than five years later, you can go up on a steep hill in Las Vegas and look West, and with the right kind of eyes you can almost see the high-water mark—that place where the wave finally broke and rolled back. (66-68)

Paul Fournel suggests that Jason Murphy’s role in that dynamic was a crucial one, despite the fact that relatively few things are known for certain about him. He drove a Hudson and drank Four Roses Kentucky bourbon, often simultaneously. He visited Paris in 1953, staying first near the Place des Vosges, then in Saint-Germain-des-Prés. He had a shack on Half Moon Bay. Lawrence Ferlinghetti knew him well, and indeed had published him, which provides Paul Fournel with an opportunity to sketch Ferlinghetti in broad outline, for the benefit of his reader: “An ageless poet, with a pretty good head for money, which had allowed him to found a small, prosperous publishing house and a very wonderful bookstore, ‘City Lights,’ in San Francisco. He published and sold the whole Beat Generation. And he also translated Prévert into English, a very welcome gesture” (48). But Ferlinghetti and Murphy had a falling-out, long ago, and the former has no idea what has become of the latter in the many years since that event.

It is useful to remember that it is not the man who is of central importance here, but instead the work he produced. On the Road and Howl both circulate freely in this novel, serving as stable points of intertextual reference and sure guarantors of authenticity. Yet Fournel draws our attention more closely still to Jason Murphy’s poetry, which he quotes extensively, in the original English, complaisantly furnishing a French translation for those readers whose English might not be utterly fluent. If one steps back from the fictional world for a moment, still another reason for choosing a fictional author quickly becomes clear: it allows Fournel to invent an American poet, one who may not be the most distinguished poet of his generation, but who is nonetheless eminently worthy of our attention. One whose greatest achievement, moreover, may be yet undiscovered, just waiting for the right combination of diligence, obsession, and circumstance to reveal it. As if diligence, obsession, and circumstance had anything to do with writing—or with literary scholarship, for that matter.

x

Jean Rolin composes Savannah (2015) in a decidedly minor key, and the image of America that he provides therein is painted in muted, even melancholy, colors. The text follows a narrator closely resembling Rolin himself (so closely in fact that I shall call him “Rolin” in my account of the book), who performs what Freud called the “work of mourning,” retracing a visit to Georgia he had undertaken seven years previously with a close companion, “Kate,” who has since died. In Savannah, Jean Rolin exploits a mythology of America a bit different from the kinds we have noted thus far, one that wagers upon the belatedness of the American South, and upon the exoticism of that region, when seen in long focus by a European eye. Rolin is known for the way he puts exotic landscapes to work in his writing, whether it be that of the Congo in L’Explosion de la durite (The Explosion of the Radiator Hose, 2007), or that of the Australian Outback in Un chien mort après lui (A dead dog after him, 2009), or that of the Strait of Hormuz in Ormuz (2013). Here, however, many of the terms upon which Rolin relies in order to construct place and mood have been conveniently codified well before he puts them to use, by the writers of the Southern Gothic.

Among those latter figures, Flannery O’Connor is paramount, for it is she who interests Kate most particularly. Kate and Rolin had traveled to Milledgeville, “in deepest Georgia” as Rolin puts it (11), seven years prior to the narrative present of Savannah, in order better to understand O’Connor, with Kate filming more or less constantly along the way and in the town itself. Now, Rolin returns there in search of something that he never makes explicit. One might note however that such a return, in itself, is a familiar gesture in our cultural lexicon. People in mourning often do revisit places where they had been happy, even if (and perhaps especially if) they had not fully recognized their happiness at the time. What they seek may vary, but certain features are common to most of those quests: the topos of grief and the very process of grieving; the idea that one’s past happiness becomes ever more distant as one’s memory of that moment erodes; the paralyzing impression that whatever may happen now will necessarily be marked by the shadow of the past. Yet something else is going on in Savannah too, I think, something beyond a remembrance of things past. For Jean Rolin could just as easily have situated his book in France, after all, in a landscape far more familiar to him and to his French readers. That he should choose the American South suggests that there is something about that place that he finds particularly intriguing, something closely suited to the expressive needs that animate his project. I wonder if it might be possible to trace that “something” through the cultural commonplaces that Rolin puts on display in his book.

First and most obviously, Rolin insists upon images that invoke death and commemoration. Kate had wished to visit the Colonial Park Cemetery in Savannah, in order to include it in the film she was making. Rolin returns there, now of course in a very different frame of mind, attuned to that site in ways that he had not anticipated, noting details that had largely escaped him during his first visit. Among other cemeteries, Laurel Grove, also in Savannah, had also interested Kate, with its “lawns, scattered headstones, trees from which hung long beards of moss” (108-109); and Rolin returns there, too, visiting Hillcrest Cemetery, Catholic Cemetery, and Bonaventure Cemetery for good measure. That itinerary, and more particularly the account of that itinerary, serves to remind us that Savannah itself is a memorial of sorts. It is what the French call a tombeau, a tomb, a literary form serving to memorialize an individual who has died. The most famous of those tombeaux is perhaps Mallarmé’s sonnet, “The Tomb of Edgar Poe,” but there are many other examples of the genre; and it is a tradition that Rolin exploits massively.

Another set of images that Rolin puts into play involves low-end Americana. Motels figure heavily in that semiotic—as indeed they have done since Nabokov. Rolin alludes to a modest motel in Savannah “situated on the corner of River Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue” (18) where he and Kate had stayed. But when Rolin tries to locate it in an Internet search in order to stay there again, he finds that “it had disappeared between then and now, leaving no trace other than the markedly negative comments of its last guests, some years previously” (23). Sic transit gloria mundi. Thankfully, other motels have sprung up to take its place, notably “the Best Western motel, situated at the intersection of Bay Street and Martin Luther King Jr. Avenue” (23). Even Milledgeville, as far-removed as it may seem, possesses its motel, about which Rolin notes, with considerable understatement, “one is not greeted in a Best Value Inn in Milledgeville like one is greeted in a Four Seasons in Washington” (89). Clearly enough, however, it is not the Four Seasons that interests him, but rather the Best Western, the Best Value Inn, and places of similar ilk.

Other unpresuming “American” places retain Rolin’s attention. The bus station in Savannah, for instance. He notes that neither he nor Kate knew how to drive a car, and that they were thus obliged to travel by bus and by taxi during their visit. Taxi drivers figure in this narrative too, of course; and they are stock types in American cultural imagery, too. Rolin is moreover fascinated by a bar called “Malones,” which touts itself alluringly as a place “Where the girls dance on the bar” (43), and by a storefront operation called “Cash Loans Until Payday” (97), and by “a landscape of desolation, that of a vastly sprawling, metastatic mall” (88), all of which seem to him to represent sites where the American Dream has gone to die. Because it is not only Kate who has died: it is a whole world that has died along with her. And in just that perspective, one of the advantages of the myth of the American South becomes apparent, because that myth is founded squarely upon the notion of dying worlds.

That helps, I think, to explain Rolin’s interest in unclaimed urban spaces and wastelands of various sorts, an interest that is long-standing and that in fact inflected his relationship with his friend. “Sometimes I reproached myself for imposing upon Kate my own taste for vacant lots and disaffected port areas,” he remarks (35), a scruple that did not prevent him from taking her along to places of that sort, again and again. On several occasions in Savannah, he speaks about a power plant in the city that he admires, waxing positively lyrical when describing the sickly orange sodium light that glows within it. “Kate had become familiar with that lighting,” he remarks, “because of all the time we spent together in ports, in Saint-Nazaire, Dunkerque, or Le Havre” (43). Rolin takes pleasure in walking along the Savannah River, watching “the tugboat Florida” or “the auto freighter Tugela from the Wallenius-Wilhelmsen fleet” (41) make its leisurely way through the city. The key feature of ports, of course, is that the people and things one encounters there are always in transit—and that is a state that Rolin cultivates very deliberately indeed. “The surest way of giving oneself the impression of being left behind, of being less than nothing,” he says, “is to walk alone on the unpaved roadside of a major highway, if possible in the United States, and preferably when night is beginning to fall” (99). For in a place like that, one can tell oneself that one has come to the heart of the matter, right where the dying dream of American progress meets the waking nightmare of grief.

x

The America that each of these novels invokes is not so much a place as an idea, one that is significantly mutable and (importantly) adaptable. It matters little, I think, if the elements that compose it are immediately recognizable to an American eye, if they pass some putative test of “authenticity.” For that is not what fiction is about—most of the time, at least. For fiction has its own rules, and it exercises its own sort of tyranny in its appropriation of the real. As soon as it is integrated into a fictional world, America becomes “America”—and to the degree that the fictional world is a compelling one, that process of “Americanization” becomes more pronounced. Such an argument will strike many people as heresy, I have no doubt; yet I am persuaded that the way fiction transforms reality and adapts it to its own purposes is one of the reasons we readers keep returning to fiction. Not to escape from the phenomenal world, but rather to see it in another light, one that illuminates features of that world that we might not have recognized otherwise. Sometimes those features are so deeply imbricated in the pattern of everyday life that they become largely invisible to us; sometimes we fail to register them because they do not fit easily into the interpretational grids we habitually impose upon experience; sometimes the hierarchies we construct in order to distinguish the significant from the insignificant are not supple enough to accommodate outliers and limit cases. Sometimes as well, it’s true, we have to travel to shores far removed in space or in time from our own, in order better to understand the here and the now. From France to America, for instance, or from America to France. And back again.

—Warren Motte

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. “Analyse textuelle d’un conte d’Edgar Poe.” In Claude Chabrol, ed. Sémiotique narrative et textuelle. Paris: Larousse, 1973. 29-54.

Baudelaire, Charles. “Exotic Perfume.” Trans. William Aggeler. http://fleursdumal.org/poem/120.

—. “Invitation to the Voyage.” Trans. William Aggeler. http://fleursdumal.org/poem/148.

Collective. “Toward a ‘World Literature’ in French.” Trans. Daniel Simon. World Literature Today 83.2 (2009): 54-56.

Fournel, Paul. Jason Murphy. Paris: P.O.L, 2013.

Gilman, Sander. Inscribing the Other. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1991.

Kerangal, Maylis de. Naissance d’un pont. Paris: Gallimard, 2010.

Montalbetti, Christine. Journée américaine. Paris: P.O.L, 2009.

—. Plus rien que les vagues et le vent. Paris: P.O.L, 2014.

—. Western. Paris: P.O.L, 2005.

—. Western. Trans. Betsy Wing. Champaign: Dalkey Archive Press, 2009.

Rolin, Jean. L’Explosion de la durite. Paris: P.O.L, 2007.

—. The Explosion of the Radiator Hose. Trans. Louise Rogers Lalaurie. Champaign: Dalkey Archive Press, 2011.

—. Savannah. Paris: P.O.L, 2015.

Thompson, Hunter S. Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream. New York: Random House, 1971.

Viel, Tanguy. La Disparition de Jim Sullivan. Paris: Minuit, 2013.

x

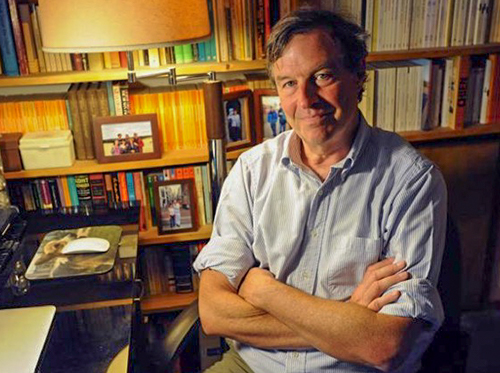

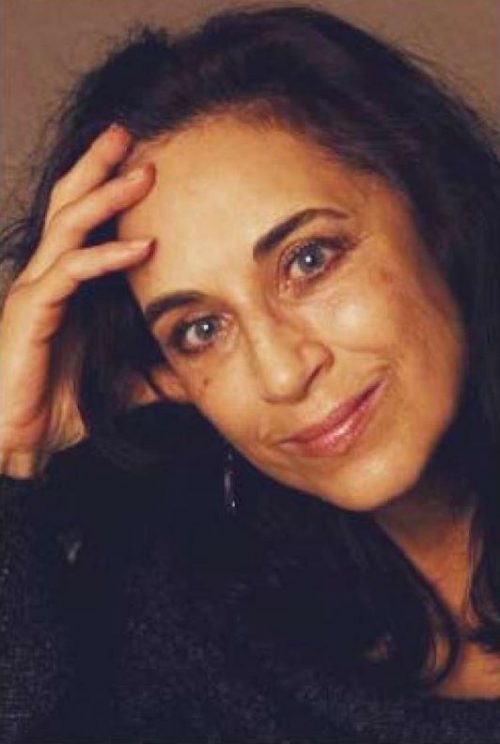

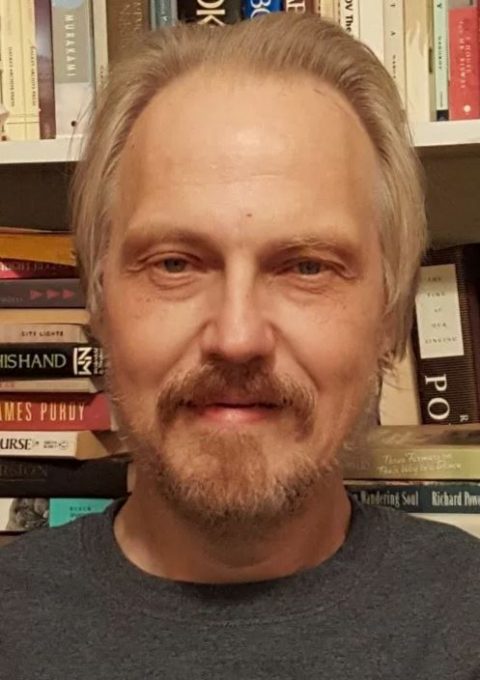

Warren Motte is Professor of French and Comparative Literature at the University of Colorado. He specializes in contemporary writing, with particular focus upon experimentalist works that put accepted notions of literary form into question. His most recent books include Fables of the Novel: French Fiction since 1990 (2003), Fiction Now: The French Novel in the Twenty-First Century (2008), and Mirror Gazing (2014). He lives in Boulder with a wife, two sons, and a couple of dogs, in a house full of books.

x

x

Jean-Philippe Toussaint

Jean-Philippe Toussaint

Hélène Lenoir

Hélène Lenoir The Red Queen and the Red King in “Through the Looking-Glass And What Alice Found There” (1871).

The Red Queen and the Red King in “Through the Looking-Glass And What Alice Found There” (1871).

Oedipus and the Sphinx (detail) by Gustave Moreau

Oedipus and the Sphinx (detail) by Gustave Moreau Karin Fossum

Karin Fossum Jo Nesbø

Jo Nesbø

Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Cynthia Flood

Cynthia Flood

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.