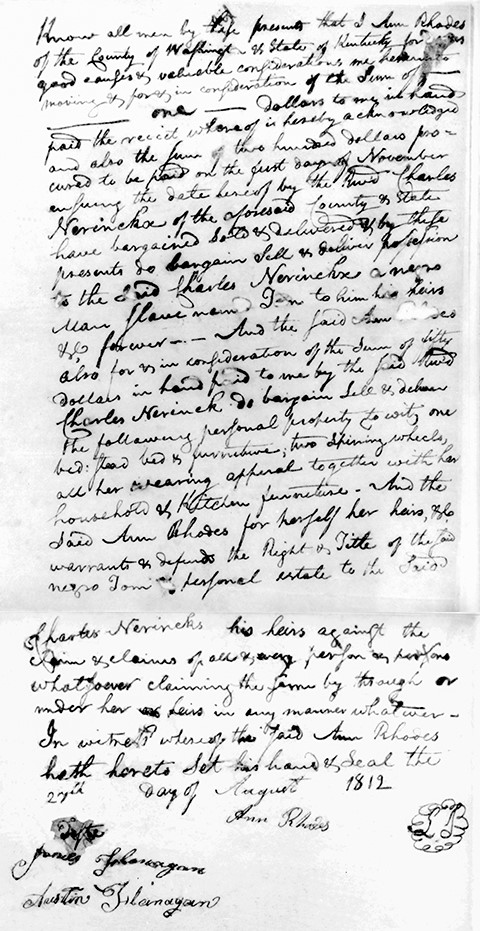

Milwaukee, 1968. Milwaukee Journal photo.

Milwaukee, 1968. Milwaukee Journal photo.

Dorothy Day images courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University Libraries.

.

Reading Dorothy Day makes me want to write radically, according to the Latin definition of the word, meaning from the root. Everything she wrote—novels, articles, letters, diary entries—was rooted deeply in her political, social, and spiritual beliefs. And she lived the way she wrote—freely and richly—eschewing convention, however society happened to define it. As Victorian norms still enshrouded America, she moved alone from Chicago to New York to live and work and find love where she might. Yet during the sexual revolution of the 1960s, when a whole generation was challenging traditional marital values, she upheld them firmly. In terms of social justice, her inclinations tended to be years ahead of most of her contemporaries. She fought on the cusp of practically every crucial social movement of the twentieth century—against the war in Vietnam, against the Atom Bomb, on behalf of Civil Rights, labor, and suffrage. She didn’t just live as a Catholic, she lived according to Gospels, stripping herself of her possessions because Christ had commanded it, loving the poor—truly loving them, which was an act of will, because the poor, up close, can be horrifying. As I read through her published works, her type-written notes, and her scribbled manuscripts, I can find nothing that she didn’t do with passion. She lived passionately, again, going to the root of the word, meaning to suffer, and she suffered in living and loving. Dorothy suffered as a lifelong habit, because she believed that to suffer was to understand Christ, and like all mystics, she dreamt of crossing through the mirror and meeting her God face to face. She wrote long rambling letters that journeyed the world and back and always ended with love of God and man alike. “The final word is love,” she copied over and over in her works.

Dorothy Day, 1930s.

Dorothy Day, 1930s.

Before I began this project I was most familiar with the famous Dorothy, the post-conversion Dorothy, the one she wanted us to see, the woman who landed in prison at the age of seventy-five for protesting alongside Cesar Chavez and the California grape workers. I knew less of her earlier commitments to causes and quandaries that have since fallen out of fashion or have, in some sense, been resolved such as socialism, anarchism, free love, New Womanhood. The first time I read The Long Loneliness, her 1952 spiritual memoir, I understood that she had always been radical and had always written with and about passion. When I read her first novel (now out of print) I was shocked at its transgressive nature. Who described the physical effects of abortion in the 1920s? Who even admitted to having one, a fraught subject even today? I resolved to write with honesty, to embrace the uncomfortable, to write as a whole person, both flesh and spirit, but most of all to write passionately, from the root.

Dorothy radically invested herself into every action, whether it was motherhood, journalism, farming, or prayer. Yet she was also a radical in the conventional sense, throughout her life belonging to multiple fringe groups who advocated for extreme social change. After leaving home in 1916 at the age of nineteen, she moved to New York and embarked on an adventurous career in journalism. Her jobs writing for the socialist paper the New York Call and The Masses introduced her to Greenwich Village intellectuals like John Reed, Floyd Dell, Max Eastman, Crystal Eastman, Eugene O’Neil, Emma Goldman, Neith Boyce, and Louise Bryant. In their company as well as that of lesser known cohorts, Dorothy experienced Communist sympathizers, the suffrage movement, Margaret Sanger’s birth control campaign, and wrote, protested, and debated about them long into the night. She wrote her first novel in 1924 and began another (never completed) in 1932.

Her family raised her to be nominally Protestant, but they never practiced or attended services. She converted to Catholicism in 1927 while living on Staten Island, shortly after giving birth to her only child, Tamar Batterham. Her conversion irrevocably changed the trajectory of her life, as it enforced a separation from her partner and father of her child, Forster Batterham, an anarchist who hated organized religion. In 1933, she encountered Peter Maurin, a French peasant philosopher with radical notions about returning the worker to the land, opening houses of hospitality in the cities, and spreading these ideas through a newspaper. And thus the Catholic Worker movement and newspaper was born. The first Hospitality House on Manhattan’s Lower East Side fed, clothed, and housed the poor and unemployed who languished in New York during the depths of the Great Depression.

While she herself maintained a pre- and post-conversion narrative of her life, the values of the Catholic Worker were every bit as radical as those of the Greenwich Village set. Through the newspaper, public appearances, rallies, and protests, Dorothy Day and the other CW members advocated pacifism, non-violent resistance, opposition to capitalism, and support for labor. What she wanted was not just better wages and more reasonable working hours, but an upheaval and transformation of existing society, an entire revolution, but one carried out with love, the only weapons being education and mercy.

Although she remained a committed journalist throughout her life, she never wrote another novel after The Dispossessed and focused instead on spiritual memoir, including her most famous work, The Long Loneliness. Despite the shifts in genre, her writing continued to be informed by radicalism and feminism as much as by orthodox Catholicism. She beautifully articulated contemporary social problems through the tropes of Christian mysticism. She continued to concern herself with the place of women within the family structure as well as with the centrality of sex in human interactions. Moving on from her earlier explorations of free love, she employed the language of desire to articulate her search for the divine that embraced both the spiritual and sensual.

ca. 1925.

ca. 1925.

,ca. 193.

Bohemian Romances

While other cities, including Dorothy’s native Chicago, were experiencing a similar renaissance in gender relations, in the nineteen teens, New York was truly the radical heart of American modernity. Greenwich Village, in particular, attracted intellectuals fascinated by the lure of change, whether it was in the arena of politics, labor, or sex. They wrote novels and plays and started newspapers to disseminate their ideas across the country. Some of the leading figures were immigrants from Eastern Europe like Emma Goldman. Others were scions of prominent families who had attended Harvard and Vassar like Crystal Eastman, Hutchins Hapgood, and John Reed. Most of them found inspiration in the socialist, communist, and anarchist movements in Russia and envisioned the day when a similar revolution would sweep America. If people wanted to write, express themselves, and generally experience life at the turn of the century, they dreamed of Greenwich Village.

Dorothy’s arrival in New York coincided with “a world in which modern women were encroaching on the formerly all-male turf of college, office, and street.”[1] Women were visible in ways their mothers had not been, and at least in Greenwich Village, several of their male colleagues welcomed that visibility as part and parcel of a new social order. Sexual equality was integral to the values of the Bohemian set. As Christine Stansell writes in American Moderns: Bohemian New York and the Creation of a New Century, “Throughout the left intelligentsia, the emancipated woman stood at the symbolic center of a program for cultural regeneration.”[2] Financial independence, free speech, and political activism were all tenets of early-twentieth century feminism. Many of the women Dorothy met in New York were supporting themselves as journalists, playwrights, editors, novelists, artists, and political advocates. She remembered that “everyone on the city desk was writing a play or a book.”[3] Louise Bryant also worked for The Masses and during the war would move to France to work for the wire services. She would publish several books on Russian politics as well as plays. Ida Rauh, the wife of Dorothy’s editor Max Eastman, was a trained lawyer and active suffragist, as was his sister, Crystal Eastman. After the government shut down The Masses, Crystal Eastman would edit a new paper, The Liberator, for which Dorothy would work. Neith Boyce was another journalist who interacted with Dorothy socially at the Provincetown Players, where they were both involved in amateur dramatics.

Sexual freedom was part and parcel of New Womanhood in the teens. Dorothy’s experience was thus different from that of late Victorian female freethinkers and activists like the settlement house workers and the first female college professors. Husbands and children represented the horrors of domesticity they had longed to escape. Marriage and a career were seen as incompatible.[4] “But with the supposed emergence of a sphere where men and women mingled in all sorts of all sorts of meaningful ways, work no longer obviated the possibility of heterosexual love.”[5] For Dorothy and her contemporaries, true equality meant the right to socialize with male coworkers at the end of the day with the possibility of romance later in the evening. As Dorothy remembered of those years, “No one ever wanted to go to bed, and no one ever wanted to be alone.”[6]

The Greenwich Village radicals were tight-knit to the point of being incestuous. Men and women formed passionate friendships and collaborated on artistic endeavors. Dorothy’s co-workers on The Masses, John Reed and Louise Bryant, were the quintessential Bohemian power couple, living together and later marrying. Louise Bryant also had an affair with the playwright Eugene O’Neil. Reed, for his part, had been involved with Mabel Dodge, another writer on The Masses, who had also been romantically linked with Hutchins Hapgood, a prominent writer in the Greenwich Village circle and husband of journalist Neith Boyce. Terry Carlin, a friend of Dorothy’s and Hapgood’s muse for his novel An Anarchist Woman (1909), lived for a time with Eugene O’Neil.

Dorothy formed attachments to various men both inside and outside these circles. She developed a deep friendship with Eugene O’Neil as he was recovering from his tormented relationship with Louise Bryant. He would drunkenly recite poetry for her at a bar nicknamed the Hell Hole, and in The Long Loneliness she credits him with stirring the already deep wells of spiritual hunger in her.”[7] After staying up late all night with him she would occasionally run into a church for a morning mass. Later she fell deeply in love with the adventurer and occasional journalist Lionel Moise. He arrived in New York at the end of World War I having worked as an editor on The Kansas City Star alongside Ernest Hemingway, who described him as a hardbitten and fearless man’s man with an air of legend surrounding him.[8] Hemingway wrote about Moise in 1952 that “what impressed me most in him was his facility, his un-disciplined talent and his vitality which, when he was drinking, and I never saw him when he was not drinking, overflowed into violence.”[9] He furiously countered the argument (originating in Charles Fenton’s The Apprenticeship of Ernest Hemingway and repeated in multiple biographies) that Lionel had taught him how to write while simultaneously mythologizing him. “I remember him as a sort of primitive force, a skillful and extremely facile newspaper man who had his troubles and his pleasures with drink and women.”[10]

Lionel Moise’s rough attractions beguiled Dorothy, who later wrote in a letter to her partner Forster Batterham that “I’ve never loved anyone but you and Lionel.”[11] She remained involved with him on and off through the early 1920s. Although still in love with him, in 1920 or 1921 Dorothy married Berkeley Tobey, the business manager for the socialist paper The Masses. Dorothy’s biograper Robert Coles referred to Tobey as “a strange man about whom little is known beyond gossip.”[12] I found a listing for him in a compilation of notable characters of Haworth, New Jersey, hilariously describing him as “a Greenwich Village rogue and bon vivant, married somewhere in the neighborhood of eight times.”[13] His last wife was the well-known California architect Esther McCoy. The photograph I saw shows a jovial man with a white walrus mustache, and is very much in keeping with the little I know of him, as he was posing next to three much younger attractive women, including Theodore Dreiser’s wife. His marriage to Dorothy lasted less than a year. She rarely mentioned him in her writing and never mentioned her marriage in The Long Loneliness, her memoirs of these years. By then, she had become a public figure due to her activism and was deliberately vague on the specifics of her romantic life before Forster Batterham. She always expressed her disapproved of Emma Goldman’s “tell-all” memoirs that named each of her lovers and recalled being “revolted by such promiscuity.”[14] But while she later insisted upon her personal privacy, her writing in the 1920s quite openly explored the new sexual freedom she was living.

In terms of its honesty about sex and relationships from a female perspective, Dorothy’s novels The Eleventh Virgin and The Dispossessed were very much in sync with the work of her fellow writers and intellectuals, Louise Bryant, Crystal Goodman, Neith Boyce, and even, despite her dislike of her, Emma Goldman. They wrote sexually independent heroines into their novels and plays and they explored its real-life implications in treatises and articles. In her 1908 novel, The Bond, Neith Boyce chronicles the first stormy years of the marriage of Basil and Theresa. Theresa, a sculptor, struggles to maintain her artistic freedom despite the obligations of motherhood and household. She also refuses to accept Basil’s double standard regarding fidelity. After he has an affair with a wealthy widow, she insists on open flirtations with other men, although she never allows them to become physical. She employs the phrase, “balancing the account,” to counter Basil’s anger. Despite their mutual misunderstandings and jealousies, Theresa and Basil remain in love and enjoy a sexually satisfying relationship.[15] Boyce’s 1921 one-act play Enemies picks up these themes. A husband and a wife, named simply “She” and “He,” argue back and forth about the inconsistencies and unhappinesses of their marriage. He complains she cares nothing for housekeeping and pays no attention to his interests. She retorts that he intrudes on her inner space and reveals her anger at his inability to remain faithful. In return, he insists, infuriatingly, that a husband’s infidelity means nothing, although a wife’s fidelity must remain paramount. At the end of the play, the two embrace and declare their mutual love and desire, although they admit they will continue to quarrel over these issues for years to come.[16]

Theresa and Basil’s fictional marriage, as well as the anonymous marriage in Enemies mirrored several key questions of the day for feminists—double standards regarding fidelity in marriage, the availability of birth control, female independence within a marriage, and the possibilities of balancing household responsibilities with domestic duties. Crystal Eastman explored these issues in a series of articles and essays for a variety of periodicals, including Cosmopolitan, The Birth Control Review, Equal Rights, and her own The Liberator, for which Dorothy would also write in the late 1920s. Most notably, in her 1923 Cosmopolitan article “Marriage under Two Roofs,” she proclaimed the merits of wives living apart from their husbands, a practice she insisted upon in her own marriage.[17] She advocated as well for husbands who took on housework, and for short hair, short skirts, legalization of prostitution, and ready access to birth control. As she wrote in a 1918 article for The Birth Control Review, “We want this precious sex knowledge not just for ourselves, the conscious feminist; we want it for all the millions of unconscious feminists that swarm the earth, —we want it for all women.”[18]

Neith Boyce, Crystal Eastman, and other Greenwich Village women writers were exploring untrodden territory. As Christine Stansell explains,

American Victorian culture had bustled with sex talk in its own segregated, covert ways. But nineteenth-century women’s ability to speak as sentient sexual beings had been limited by a melodramatic vision of decent women’s victimization by men’s lust. Outside pornography, the words were literally lacking to speak of female desire. Now, the garrulous exponents of free love broke with the asymmetrical pattern by according women a voice and transforming the male soliloquy into a conversation between the sexes.[19]

Dale Bauer terms this language as sex expressionism. “As sexuality became more public, the rhetorics of both the body and language could express sexual desire . . . women writers began to treat sex, once considered an urge or impulse, as a conscious act and a choice, deliberated, enacted and embodied.”[20] Dorothy employed “sex expressionism” to describe both the chaotic internal life and the free-spirited external life of her heroine in The Eleventh Virgin.

The Eleventh Virgin chronicles the sexual awakening of June Henreddy. It begins with her first feelings of desire as a teenager for an older married neighbor and ends with her abortion and the painful end of an affair in her twenties. June’s body stirs, shivers, and shudders with desire. Later it spasms in pain while rejecting the fruit of those desires. The discourse surrounding desire is just as important as the act itself. June is only sexually active in the ending chapters; but the expression of her desire permeates the entire book. First comes the adolescent crush on a neighbor. The relationship exists entirely in June’s imagination, but Day is clear about the physical effects on the young girl. “Her mind had never seemed to be connected with her body and it was strange and wonderful that a thought, a glance, could make a little shower of delight run through her.”[21] The delight is both emotional, physical, and entirely welcome, as June admits that “she loved to be bitten by fierce emotion.”[22] All nature seems to June to be in harmony with her desires. “A breeze sprang up as the sun settled on the sky line, and stirred the wisps of hair around their [June’s and her sister’s] hot faces. It was like a caress and June thought of Mr. Armand’s long fingers.”[23] Mr. Armand’s presence awakens June to the sensual possibilities of her body, but the experience is isolated and predictably, goes nowhere.

Over the next few years, June enjoys platonic friendships with any number of men at college and in the newspaper offices where she finds employment. She even moves in with three jovial co-workers, to the horror of her mother. Despite the constant male companionship, however, she is quite clear that she feels nothing to compare to the physical effects of Mr. Armand. She avoids romantic relationships, insisting that sexual attraction as well as emotional sympathy be present. June is a quintessential New Woman, in that her relationships with men are solely a matter of preference. Since she supports herself through writing, marriage possesses no financial incentive for her and thus she literally can afford to wait.

When she does meet a man who attracts her, Dick Wemys, she is frank about her sexual hopes. “He gave himself three months to stay in the hospital. June gave him three months in which to seduce her.” Dick works as an orderly at the hospital where June trains during the influenza epidemic. With no intentions of marring June, he would have been termed a rake had the book been written fifty years before. In the frank sexual expressionism of June’s world, however, he admits his devious plans up front. “”I love you, June. I love you more than anything in the world, today. But I can’t say how I’ll feel tomorrow.”[24] June accepts his lack of commitment and plunges ahead with the relationship. She doesn’t just love, she flirts, engaging in playful talk about sex. “I’m a demi-vierge,” she informs Dick coyly.[25] When they discuss the future, it is in terms of her physical submission to him, rather than any plans for marriage, children, or future adventures. After he announces he is leaving the hospital, he invites her to live with him temporarily—the temporary is emphasized, as is the physical nature of the request, when he shoves a card with his address in between her breasts. June’s arrival at his apartment signals to both of them the end of her virginity, which is subsequently lost discreetly, but clearly, in a break between two paragraphs.

He looked as though he were suffering. If he would only take her, push aside this barrier of sex that was between them, he could grip hold of himself again. And [she,she] could breathe easily once more and her heart wouldn’t ache so in her breast. To get the first pain over with! She bit his neck contemplatively.

He shook her so suddenly that she cried out, started, and then noticed that it was very still and quiet. When he turned town the lamp there was only the painful thumping of her own heart.

Later in the evening, June sat cross-legged on the bed in a pair of pajamas which were far too big for her and ate with a great deal of relish an anchovy toast sandwich and stuffed olives. She felt very young and childlike.[26]

Despite the frankness of June’s sexual enjoyment, the book harbors no illusions as to the nature of their relationship. June’s sexual freedom does not translate into sexual equality. For the first time since leaving home, she stops working, at his direct request. “‘While you’re mine, you’ve got to be all mine, so you needn’t have any interests outside of me.’”[27] Dick’s love is violent, possessive, and controlling. June finds herself lying to please him, “You’re nothing but a damn little fool so don’t you dare tell me Conrad knows how to write a story. I tell you he doesn’t so you might as well shut up.”[28] She wasn’t even allowed to look as if Conrad could write novels. She secretly goes ahead and reads all she pleases. While it had been up to her to yield her virginity, he dictated the subsequent terms of the relationship, reserving the right to decide alone when it would end. He also warned her that he would leave immediately should she become pregnant, which indeed, he does, even though she has an abortion. Christine Stansell notes, “Paradoxical, self-deluding, sometimes harmful: without question there was a dark edge to sexual modernism.”[29]

June’s abortion is rendered in graphic terms. Day is as frank about June’s bodily reaction to pain as she had been about its receptivity to pleasure.

One pain every three minutes. How fast they came! It seemed that the moments of respite could be counted in seconds. The pain came in a huge wave and she lay there writhing and tortured under it. Just when she thought she could endure it no longer, the wave passed and she could gather up her strength to endure the next one.[30]

There were few literary precedents for such a description, although the topic was proving to be incredibly popular among young writers, including Ernest Hemingway, and Dorothy’s friends Floyd Dell and Eugene O’Neil. Mr. Durant, a story by Dorothy Parker appeared the same year (1924) as did the incredibly successful novel The Green Hat, by Michael Arlen.[31] Theodore Dreiser’s American Tragedy was published in the following year. Over fifty more novels and short stories would tackle the controversial subject before 1945.[32] While The Eleventh Virgin remains one of the least known of these works, it proves that Dorothy was at the forefront of the significant literary discourse surrounding illegal abortions, a discourse that privileged female bodily experience. The Eleventh Virgin ends shortly after June Henreddy’s abortion, so Dorothy allows her little time to reflect upon it. The morality of abortion nevertheless remained a significant theme in her later essays and articles, as I will discuss later.

Historian James Fisher writes that “The Eleventh Virgin showed that Day was not a novelist,” and Robert Coles calls the plot “wretched.”[33] I actually found The Eleventh Virgin highly enjoyable, if somewhat immature. The most charming aspect of the writing is Day’s own bemused attitude towards the melodramatic excesses of her heroine: “‘I’ve got to have you,’ she [June] told him [Dick]. ‘I love you. I do love you. It’s a fatal passion.”[34] There is a sense of fond reminiscence over June’s willingness to throw everything to the winds in the name of love, tinged with a growing bitterness as Dick’s behavior grows more untenable.

Coles, Fisher, and historian of American Catholicism Jim Forest frequently refer to it as her autobiographical novel and glean its pages for details of her early years. It is certainly tempting to read The Eleventh Virgin as a thinly veiled autobiography of Day’s early years in Greenwich Village, although I am loathe to place experiences in Dorothy’s own life on the sole evidence that they appear in the novel. Certainly June’s adventures in writing and politics mirror Dorothy’s own as she described them in The Long Loneliness. The book also embarrassed her after she became a well-known public figure. “There was a time that I thought I had a lifetime job cut out for me—to track down every copy of that novel and destroy all of them, one by one.”[35] At least some of the book did echo her own experiences. She revealed in letters and diaries that she did have an abortion during her relationship with Lionel Moise and preceding her marriage to Berkeley Tobey. As she related in The Long Loneliness, she sought spiritual solace during this time, and there are also hints of a kindling religious interest in the adolescent June, who rebels against the coldness of her parents by a passionate devotion to God, although once she leaves home she grows absorbed in other pursuits.

The Eleventh Virgin, however, documents sensuality rather than spirituality, and the heroine, at least, sees a clear separation between the two. As the adolescent June writes to a friend,

All these feelings and cravings that come to us are sexual desires. We are prone to have them at this age, I suppose. [The fifteen-year-old intoned piously.] But I think they are impure. It is sensual and God is spiritual. We must harden ourselves to these feelings, for God is love, and God is all, so the only love is of God and is spiritual without taint of earthliness.

Given that the subject of religion is then dropped in the novel, there is no sense that the author had reconciled them either.

With her daughter, ca. 1932.

With her daughter, ca. 1932.

.

Conflict and Conversion

Dorothy’s next novel explores both the sensual and spiritual. She wrote the first chapters during 1932, when she had moved back to New York after working briefly in Hollywood as a screenwriter and then traveling for a year in Mexico. She had already converted to Catholicism although she had not yet met Peter Maurin and begun the Catholic Worker. Most of her time was spent writing for Catholic newspapers and magazines and working on the novel she would term both The Dispossessed and This Dear Flesh. As she describes those months in The Long Loneliness:

I was writing a novel. I have always been a journalist and a diarist pure and simple, but as long as I could remember, I dreamed in terms of novels. This one was to be about the depression, a social novel with the pursuit of a job as the motive and the social revolution as its crisis. There was to be the struggle between religion and otherworldliness, and communism and this-worldliness, replete with a hero and a heroine and scores of fascinating characters. I put my own struggle and dreams of love into the book and was very happy writing it.[36]

The Dispossessed documents the conversion to Catholicism of a young girl named Monica as well as her love affair with a Communist she knows she can never marry. As with The Eleventh Virgin, Day frankly explores the physicality of Monica’s desire. Monica has loved Nick ever since she moved into the apartment next to him as a little girl. But as she reaches adolescence, her love assumes a physical dimension. She doesn’t just love him; she desires him.

At this time Monica began to be obsessed with desire for him. When he was away, she saw him everywhere, in the line of head, the attitude of some stranger. She heard him in a sudden soft laugh. The river noises and the heavy damp smell of the city those early spring days reminded her of walks they had taken, long wordless hours they had spent together.[37]

Day employs metaphors of heat and hunger. Monica feels “hot within herself” and is “hungry to love.”[38] Her sexual awakening coincides with an equally passionate religious awakening. The only thing in her life that evokes the same level of emotion and physicality within her is Catholicism, which ironically means that she can never succumb to her desire for Nick. Her experiences of the depths of her faith resonate physically in her body, and Day employs similar language. One morning, Monica impulsively follows a young woman to Mass:

It was almost every Mass in the Italian Churches, and Monica sat during the Gloria in a maze of happiness. She did not know why she was happy, why this sudden glow of joy had come into her life. She felt waves of exalted thankfulness flooding her heart,a sudden intense consciousness of an all-loving God, and the need and hunger of the human heart in its desire to serve Him to worship Him. The Mass satisfied her as it never had before. And somehow all this sudden realization was linked up with that girl, so still, so breathlessly still and radiant.”[39]

The two desires are intricately connected and spur each other to greater heights. “Monica’s love for Nick made her realize her faith, because young though she was, she recognized that a choice was being put up to her. She could not have him and her Church too.”[40] It is difficult for the reader to form an opinion one way or another regarding her choices, since each option stirs her equally to physical and emotional frenzy.

Monica sought refuge in her religion now, but she distrusted the softness of religious emotion during these hard times. It went hand in hand with the melting tenderness she was apt to feel at the thought of Nick. The joy and the faith which made it forbidden were too closely linked at these times in her mind. She was as unstable as a reed.[41]

Her torment expresses itself in the language of illness as well as yearning. “She felt that she was a woman with a sickness who had to cure herself.” To love is to experience passion. Passion, literally and figuratively equals suffering. It is impossible not to love and thus, not to suffer.

Unlike June Henreddy, Monica is a virgin and never speaks in terms of seduction. Marriage is the forbidden but desired outcome of her relationship with Nick. Although they cling to each other in dark corners, neither proposes going any further. Yet she is caught up in concerns about sin that June never experienced.

There came with this knowledge of her deliberate choice, the question of mortal sin. Even the thought of bodily desire (forbidden as it was in connection with Nick) was an act of unchastity in the sight of God and as such was mortal sin. Yet to have committed mortal sin . . . (it was that, – Oh God – it certainly was that) but it was not due deliberation or full consent of the will. For blindly she had fought and struggled, praying daily, walking through the misty, fogbound streets, and how could it be full consent of the will when her lips were numb at the remembrance of his kiss, and her lips were stiff as she forced them on in a mechanical round of walking.[42]

Politics also stands in the way of the young couple’s happiness. Nick also desires Monica but feels an equal calling to Communism and believes he cannot distract himself with a wife and family. He dreads the thought of prison but is equally convinced that he must end up there. The two engage in mutual torment. “’Oh, Nick, Nick, I’m so glad to see you,’ Monica cried, her hands behind her back to keep them from clutching at him. He took hold of her shoulders and his hands were trembling. ‘

“‘You know how I feel, and I can’t stand it.’”[43] It is a love that cannot be born but equally cannot be ignored.

In Monica’s yearning for an unattainable love, Dorothy articulates the mystical longings that she would explore later in her spiritual writing. According to the brief plot summary she had drawn up for potential publishers, Dorothy had planned a happy ending for the pair, each with more suitable spouses. Nick would marry the Russian emigre Natasha while Monica would fall in love with and eventually marry Raoul, an upstanding architect and a friend of Nick’s. “All would be happy according to their lights.”[44] It is fitting, perhaps, that she never composed this ending, dropping the novel in 1933 when she began the Catholic Worker. The desire that coursed through Monica’s body could not be stilled in a contented marriage. The only cure for such desire was a lifetime committed to seeking, following the trail of an elusive lover into dark nights and lonely mornings.

Towards the end of the unfinished narrative Dorothy brings in another woman as a rival for Nick’s affections. The Russian emigre Natasha, unlike Monika, is a sexually experienced woman desperately in love with Nick. Despite his earlier disavowal of marriage, he proposes to her, as her loyalties are compatible with his politics. She relates a sad tale of a promiscuous past in Russia with uncaring lovers more devoted to the Revolution than to her, and then in New York living a hand-to-mouth existence working at a cabaret (which seems to be a euphemism for a brothel). Despite her experience, when it comes to desire, she and Monica speak the same language. Her love is starvation, misery, and desperation. Even in love and engaged, she experiences torment. Nick accuses her of enjoying her misery, and she responds in explanation, “It is difficult for a passionate woman to get over the habit of being passionate.” By passion, she means not only love, but the suffering that must accompany it. Monica must renounce Nick and Natasha will marry him, but to truly experience the weight of their choices, they both must suffer in love. We don’t know how the characters will develop but love as suffering and joy in renunciation are both themes that will inform the rest of her work.

1934 (original in New York World-Telegram and Sun Collection, Library of Congress).

1934 (original in New York World-Telegram and Sun Collection, Library of Congress).

.

Love as Mystical Yearning

Dorothy’s post-conversion politics led her to conservative stances on issues such as abortion, birth control, divorce, and pre-marital sex, all of which she firmly condemned in her writings. These attitudes seem to represent a complete break from her earlier radical days when she had attended Margaret Sanger’s speeches, worked for Crystal Eastman, and stayed up nights discussing the merits of free love with John Reed and Eugene O’Neil. They also seem to contradict her own first writings which had expressed sexual desire freely regardless of marital ties and whose heroines had expressed regret only at the loss of love, not the loss of virginity or reputation. Her subsequent writing certainly appears to advocate a more traditional femininity in line with the Victorian family structure against which she had originally rebelled.

Her conversion seemed abrupt to those who knew her, but it followed years of seeking. In the years preceding her conversion, she felt increasingly drawn to the life of the spirit. In The Long Loneliness, she writes, “It seems to me a long time that I led this wavering life . . . . I felt strongly that the life of nature warred against the life of grace.”[45] She had also expressed these anxieties in The Eleventh Virgin when June Hendreddy declares that “the only love is of God and is spiritual without taint of earthliness.” Even though she was happily in love with Forster Batterham, she experienced emptiness and longing. They lived together in her cottage on Staten Island. It was the greatest happiness she had ever experienced but she still felt dissatisfied. In The Long Loneliness (1952), she articulates the idea of God as lover who drew her away from her Forster. She presents her struggle as a love triangle between herself, God, and Forster Batterham, Tamar’s father and the man she refers to as her common-law husband. “I wanted to die in order to live, to put off the old man and put on Christ. I loved, in other words, and like all women in love, I wanted to be united to my love. Why should not Forster be jealous? Any man who did not participate in this love would, of course, realize my infidelity, my adultery.”[46]

On a practical level, her conversion meant sacrificing a life that brought her much delight as well as stability after years of searching. Although Dorothy liked to refer to Forster as her husband, they were not married in the eyes of either the state or the church, and he refused to take those steps. A self-identified anarchist, he abhorred the institutions of both religion and marriage. As a Catholic, she could not live with him outside of marriage. Neither would yield. “To become a Catholic meant for me to give up a mate with whom I was much in love. It got to the point where it was the simplest question of whether I chose God or man.”[47] It is hard not to read Monica’s struggle with a love incompatible with a burgeoning faith as a reenactment of Dorothy’s own. Monica and Nick had begged each other to relent; in similar ways, Dorothy and Forster argued back and forth for almost ten years. She left him and moved to Hollywood and then to Mexico and then to Florida. He visited her occasionally to rekindle their relationship but refused to marry her. She begged him in tones alternating between seduction and despair to marry her and accept her Catholicism. In 1929 from California: “I wish you would give in. I can assure you that I would not bother you and your own opinions as long as you granted me religious liberty—that is, me and the numerous other children we’d have.”[48] In 1932: “Aren’t we ever going to be together again, sweetheart? . . . I do not see why you can’t let me and Tamar be Catholics and be happy with us just the same. You know I love you, and I always think of us belonging together in spite of us being four years apart.”[49] She didn’t give up until she met Peter Maurin and threw herself into beginning the Catholic Worker. When she wrote to Forster in December, 1932 that “I have really given up hope now, so I won’t try to persuade you any more,” she meant it. She wouldn’t write to him again until the 1950s.[50]

After she gave up hope of reconnecting with Forster, she politely but firmly put a stop to any romantic attentions and declared herself a celibate. In the 1940s, Ammon Hennacy, a former Mormon turned Catholic anarchist who had thrown himself wholeheartedly into the Catholic Worker movement became captivated by her. She fended off his advances, writing, “I have a great love for you of comradeship but sex does not enter into it.” [51] And later: “When one is celibate, one is celibate. There is no playing around with sex.”[52] He evidently still thought of her in terms she considered inappropriate when in 1953, he sent her a copy of his memoir (later titled The Book of Ammon) which she returned with pages cut out of it, pleading that such thoughts did not become their age. “It is next to impossible to write about such love of people in their sixties without either seeming ridiculous or revolting.”[53] It is unclearly exactly why she turned towards celibacy, especially considering that she still lived very much in the world. She is clear that she did not do so out of a distaste for sexual love. “It was not because I was tired of sex, satiated, disillusioned, that I turned to God. Radical friends used to insinuate this. It was because through a whole love, both physical and spiritual, I came to know God.”[54]

Day at Maryfarm, Easton, PA, ca. 1938.

Day at Maryfarm, Easton, PA, ca. 1938.

Although certainly after her struggles with Lionel and Forster, it is conceivable that she could have been fed up with noncommittal men. In 1947, she wrote angrily to a disgruntled Catholic Worker volunteer: “I should be used to men failing me. I’ve had to bring up a child alone and I’ve certainly seen more than my share of the gross and selfish in men. I’ve had many men love me but few protect me.” Although she never explicitly states this, possibly she felt the need to atone for what she considered her early promiscuity. Guilt over her behavior, especially her abortion, haunts her diary entries.

Robert Coles asked her why her she had chosen to end her romantic life at such a young age. For one who positioned sexual pleasure in the heart of the Catholic marriage and who eschewed what she termed Jansenism (a manichean distaste for the physical), why give up such a part of herself and her past? She answered him in a series of roundabout conversations. “When I fell in love with Forster I thought it was a solid love . . . that I had been seeking. But I began to realize it wasn’t the love between a man and a woman that I was hungry to find. . .”[55] In a similar vein, she wrote to Ammon Hennesy that “the whole direction of our thoughts should be to increase in the love of God. It is only in giving up a thing that you can keep it; it is only by such a sacrifice on your part that love can be beautiful and holy.”[56] In much of her post-conversion writing, love becomes directed entirely towards God in a complete mysticism. For Dorothy, nothing but God’s love would suffice.

Yet desire never loses its place in her language, describing both a longing for physical contact as well as the presence of a transcendent force. After her conversion, she reinterpreted her understanding of humanity to include both body and soul conjoined together, per God’s design. Hence the sacral nature of sex: “One cannot properly be said to understand the love of God without understanding the deepest fleshly as well as spiritual love between man and woman. The two should go hand in hand. You cannot separate the soul from the body.”[57] She devoted her whole self to seeking God as she would a lover, and that search took the place of romantic human love. She told Robert Coles: “My conversion was a way of saying to myself that I knew I was trying to go someplace and that I would spend the rest of my life trying to go there and try not to let myself get distracted by side trips, excursions that were not to the point.”[58] A husband or lover would be beside the point in her mystical journey.

In Dorothy’s spiritual writings, she beautifully articulates the sacramental nature of marriage and the centrality of sexuality in marital relationships as “a foretaste of the beatific vision.”[59] “The intense pleasure and delight in the act itself may be like a sword piercing the heart.”[60] Sex is the actual sacrament embodied in matrimony, as opposed to the vows. “It is not the promises that make the marriage. The vows are exchanged at the altar; the marriage is the embrace itself.”[61] On a practical level, she argues, then, that the church needed to emphasize the significance of marital relations and to avoid the “Anglo-Saxon Jansenism,” that caused people to shy away from such discussions. “ . . . It is time indeed that there should be more talk on the subject of sex and marriage on the part of Catholics.”[62] She refused to read the Kinsey report but was nonetheless fascinated by its willingness to bring sex into popular conversations, an inclination she argued that contemporary religious writing lacked.

It is because sex is “the most deeply wounded of all our faculties” since the Fall. In sex, body and spirit are so interwoven, so attuned, so single-minded, so concentrated, and so alive. It is in sex love that people catch glimpses of harmony and peace unutterable. That is why thwarting sex, unfulfilled marriage, is a tragedy often dealt with by physicians and psychiatrists. If the act, which is called by St. Paul “the marriage debt” is not paid generously and to the full people are warped and nerve-wracked, curiously askew.

The language of desire occupied a permanent place in her writing, but in her post-conversion writing the force of it was directed back to divine union. In On Pilgrimage, The Long Loneliness, and her many letters, diaries, and articles, she explores the theme of Christ as lover, a literary path previously trod by Dorothy’s favorite saints, Catherine of Siena, Theresa of Avila, and Therese of Lisieux as well as other great mystics whom she admired. In Dorothy’s voice, the image takes on a modern and realistic meaning. The joys are not metaphorical, and the bodily effects speak to actual memories. For the medieval mystics, the language of sexual ecstasies only existed on a metaphorical plane. For Dorothy, it as the realistic humanity behind the words that renders them meaningful—“It is because I am not now suffering that I can write, but it is also because I have suffered in the past that I can write.”[63] It was precisely because she had known the sweetness of a whole love, body and soul, that her act of renunciation was so precious. “The best thing to do with the best of things is to give them to the Lord,” she wrote in her diary decades after her conversion, “and note that fleshly pleasure if not isolated from mind and spirit is not here labeled sin, but called ‘the best of things.’”[64] So her bridal mysticism loses the morbid aspect of the medieval saints that she admired and appeals to a twentieth and twenty-first century sensibility. It makes sense that in Augustine of Hippo, another great lover of the flesh who nevertheless turned his heart to God, she found great inspiration and quoted frequently in her Catholic Worker articles. Sexual desire between humans was both a piece of and a reflection of God’s love, not divorced from it. Human love was the overflow of God’s love.

Religious historian James Fisher declared that she “came to espouse one of the most abject brands of self-abnegation in American religious history,”[65] and referred to her religious interpretations as “bleak.”[66] His interpretation denies the joyful earthiness of her spiritual writing. Dorothy never turned away from the reality of flesh, delighting in her body even when it sickened and aged, so that she could write on Valentine’s Day, 1944 in her diary:

But this aging flesh, I love it, I treat it tenderly, but also rejoice that it has been well used, that was my vocation—a wife and mother, I gave myself to husband and children, my flesh well used, droops, my breasts sag, my face withers, but my eyes and lips rejoiced and love and laugh with happiness.[67]

Flesh was both her “enemy” and her “dear companion on this pilgrimage.”[68] Her acknowledgement and appreciation of bodily realities represents one of the strongest continuities throughout her writing. At the age of eighty-two, she declared firmly in her diary, “I am a sensual woman.”[69]

Day serving soup to Franciscans at Detroit Catholic Worker, ca. 1951.

Day serving soup to Franciscans at Detroit Catholic Worker, ca. 1951.

.

An Unwilling Feminist

She never retired, writing articles until her death at the age of eighty-three. Her continuing engagement with current affairs required her to confront the changing social mores of the 1960s and 1970s. The Catholic Worker could not remain static if it wanted to remain relevant. As its original members aged, the organization relied on a steady influx of younger volunteers. Dorothy treated these younger colleagues with the same mixture of amusement, concern, and bewilderment, that she showed her nine grandchildren. The young girls of the CW attended Woodstock and excitedly reported back to her. “They had a weekend of rain. Sounded like a nightmare to me,” she wrote dismissively. Her perplexity was frequently softened by outpourings of compassion, as she found her bohemian youth reflected in their untempered idealism. “Aside from drug addiction, I committed all the sins young people commit today,” she wrote in 1976.[70] She disapproved of priests who approached the drugs and sex of youth culture with a lack of understanding. “No compassion for the young,” she dismissed an otherwise good sermon that had ended with a censure of Woodstock.[71] The anti-war demonstrators of the 1960s were near and dear to her heart, as they picked up the pacifism the CW had espoused since the 1930s. In 1965 she spoke at Union Square in support of men who burned their draft cards. In 1967 she attended the trials of anti-war demonstrators and helped raise money for their defense. She differentiated them from the young men and women she deemed to be “hippies,” whom she dismissed as spoiled rebels without any causes other than non-conformity. “I felt in view of the blood and guts spilled in Vietnam the soldiers would like to come back and kill these flower-power-loving people. . . . Middle-class affluent homes, they have not known suffering.”[72] In her warmer moments, she judged them foolish but lost, as she had been and as she knew her own progeny to be. “These are my children too, my grandchildren. Having so many grandchildren, I love . . .”[73]

Dorothy firmly maintained during the 1960s that she was not a “women’s-libber,” but she did conceive of marriage, motherhood, and the position of a woman in a family in radical ways, not unlike her Bohemian companions of the 1920s. She meditates on motherhood and marriage in On Pilgrimage, a book based on a journal she kept in 1948. She spent most of the year on a farm in West Virginia with Tamar who was pregnant with her third child, and her writing reflects her domestic setting. “Meditations for women, these notes should be called, jumping as I do from the profane to the sacred over and over. But then, living in the country, with little children, with growing things, one has the sacramental view of life.”[74] On the farm, dealing with no running water, no electricity, no stores, and two small children, she found herself beset by household cares and unable to write, pray, or even think. She writes frankly about the lack of intellectual and creative stimulation mothers endured. On January 20, she writes despairingly, “What kind of an interior life can a mother of three children have who is doing all her own work on a farm with wood fires to tend and water to pump? Or the grandmother either?”[75] In a similar vein, she complains on March 8, “If you stop to read a paper, pick up a book, the children are into the tubs or the sewing machine drawers. . . . Everything is interrupted, even prayers, since by nightfall one is too tired to pray with understanding.”[76]

She compares the relative constraints of young mothers and fathers. Enviously watching her son-in-law exploring the woods, she admits “one cannot help but thinking that the men have an easier time of it. It is wonderful to work out on such a day as this, with the snow falling lightly all around, chopping wood, dragging in fodder, working with the animals. Women are held pretty constantly to the home.”[77] In On Pilgrimage, she raises a theme that would haunt her writings for years to come—Tamar’s isolation and frustration as a young mother with a new baby practically every two years (nine children in eighteen years of marriage) and no intellectual outlets. “It is a lonely life for a woman with many small children. It is a life of solitude in city and village anyway, since a young mother cannot get out, but in town neighbors and friends can at least drop in.”[78] Her correspondence with Tamar is rife with comforts and reassurances that rarely seemed to work. When Tamar longed to move back to New York so she could have more company, Dorothy warns her away because of the polio epidemic and the high rents. “Oh dear. I do know how lonely you are, but I do assure you that a mother with small babies is always lonely.”[79] She titled her book The Long Loneliness in part as a reference to the shared solitude of humanity. But she also meant to pay specific homage to the particular loneliness of women, both as young mothers isolated by the burdens of childcare and then later as older mothers bereft of their children. “Tamar is partly responsible for the title of this book in that when I was beginning it she was writing me about how alone a mother of young children always is.”[80] Dorothy realized, of course, that loneliness and anxiety were the bitter but necessary fruits of motherly love. “It is right for us to love our families, but oh the heartaches. But it is the cross, the saving Cross. We cannot have Christ without His Cross.”[81]

Tamar’s experiences, both her loneliness and her restlessness, paralleled Dorothy’s own as a young mother. She remembered herself as a young mother traveling from New York to Hollywood to Mexico and back again. “I was lonely, deadly lonely. And I was to find out then, as I found out so many times, over and over again, that women especially are social beings, who are not content with just husband and family, but must have a community, a group, an exchange with others.” That loneliness can stem from specific circumstances—Dorothy knew almost no one in Hollywood and likewise, Tamar lived in the country miles from a neighbor. But it also derives from social pressures and biological realities that isolate women in households. In a statement that stunningly echoes Betty Friedan’s work of the following decade, she continues by declaring that, “ A child is not enough. A husband and children, no matter how busy one may be kept by them, are not enough.” Women needed to create and seek outside the family structure. Even flush with love for her new baby, she had still been driven to write. Back in her cottage on Staten Island, still with Forster, her Catholic sponsor Sister Aloyisia had scolded her for sitting at her typewriter while the breakfast dishes piled high. Dorothy’s own conversion, for all that it that it represented a more conservative social stance, actually entailed an assertion of autonomy, radical in every sense.

Dealing with birth control, abortion, and free love were the most troubling aspects of the 1960s and 1970s for her, both because they conflicted directly with Catholic family doctrine and because they reminded her uncomfortably of her own youth. Her disapproval of birth control brought her into conflict with her sister Della, who volunteered at Margaret Sanger’s clinic and openly declared she would only have children she could afford to bring up and send to college. Dorothy writes in Della’s obituary: “When she went on to exhort me . . . that I should not urge, as a catholic, Tamar, my daughter, to have so many children, I got up firmly and walked out of the house, whereupon she ran after me weeping, saying, ‘Don’t leave me, don’t leave me, We just won’t talk about it again.’”[82] Her advocacy of marriage without birth control continually warred with her championing of female independence. Had she remarried and given birth to more than one child, her ability to travel the country and write would have been greatly curtailed. In 1973 she wrote to Sidney Callahan, a professor of psychology at Mercy College, “I feel badly at seeing formerly happy women friends bitter and angry at all they have suddenly discovered they have suffered. And they get angry at me for not being angry.”[83] Yet even though she disliked the label of feminist, she continued to be attracted to the ideals they championed. She disapproved of bishops who were “more concerned about [birth control] than war.”[84] By 1979, after hearing Dr. Marian Moses speak, she admitted there was validity to the feminist critique of the papal stance on birth control and abortion. “She is a strong feminist. I am not, tho I can see all the problems.”[85]

Interestingly enough, while her disdain for birth control seems like mere unquestioning acceptance of Catholic dogma, on a few occasions she expresses her belief that birth control harmed women in particular, as it allowed men to escape marriage and responsibility. “Sex is a gigantic force in our lives and unless controlled becomes unbridled lust under which woman is victim and suffers most of all.”[86] The sexual revolution seemed to give men license to leave their wives, which she witnessed frequently in the CW. Divorced women with small children took refuge as part volunteers and part boarders. “Dear God, help me not to judge people harshly. But men certainly take advantage of women more than ever these days.”[87] Her critique of the sexual revolution sounded a familiar feminist note. As Ruth Rosen explains in The World Split Open, men happily exploited women’s newfound sexual availability. “If sex was free, where did you draw the line?” She related the tale of one woman in a Washington D.C. consciousness-raising group who lamented that “the sexual revolution is making me miserable,” because “I’m not supposed to be jealous” when her husband cheated on her with “everything in sight.”[88]

Thirty years prior, Dorothy had angrily accused Forster of just such flippancy in their relationship when he refused to marry her.

You have always in the past treated me most casually, and I see no difference between [our] affair and any other casual affair I have had in the past. You avoided, as you admitted yourself, all responsibility. You would not marry me then because you preferred the slight casual contact with me to any other. And last spring when my love and physical desire for you overcame me, you were quite willing for the affair to go on, on a weekend basis.[89]

In a roundabout way, she argued that birth control allowed for promiscuity, which created an easy escape from marriage, which was the ultimate sacrament. Given her experiences with Forster and Lionel Moise, perhaps Dorothy assumed most men would avoid marriage if offered sex and most women would choose it. The legalization of abortion after Roe v. Wade in 1973 struck close to home. “Does the changing of laws—the Supreme Court decision—do away with this instinctive feeling of guilt? My own longing for a child.”[90]

The separation of love and sex troubled her, not only because it led to the dissolution of marriage but because of its ubiquity, even in the sanctuaries of the Catholic Worker homes and farms. It overwhelmed impulses for pacifism and charity that she tried to hone in new workers. “What to do about the open immorality (and of course I mean sexual morality) in our midst. It is like the last times—there is nothing hidden that shall not be revealed.”[91] She worried that contemporary thought urged people to succumb to their desires. “[They say] why does God implant in us these instincts and then punish us when we satisfy them? God made all things to be enjoyed. Enjoy! Enjoy!”[92] Her conversion was based on denial of instinct; she relied on discipline and prayer to strengthen her resolve when old temptations beckoned. She had renounced love only to find a deeper love and a greater life. She found something vacuous about those who searched without sacrifice. “My heart aches for them, they are so profoundly unhappy. Their only sense of well-being comes from sex and drugs, seeking to be turned on, to get high, and to reach the heights of awareness, but steadily killing the possibility of real joy.”[93]

Yet Dorothy believed in love, even if it was free. Despite her adherence to Catholic moral teaching, she couldn’t condemn a relationship in which love had sprung up between two people, even if the love lacked sacrality. “Birth control, abortion, free love—all in the name of love. . . . The hunger for human love, how beautiful in marriage and renunciation, too. But it is always to be respected, even in all these free unions, even in all these sad searchings . . .”[94] As the seventies crawled on, her own and the century’s, the world continued to change, and she insisted on reexamining her priorities and values. Old friends and colleagues started coming out as gay and she strove to understand what the church condemned. When two of her female friends confessed to her they were lesbians, she sought back into her past to remember moments of similar feeling—again, she strove to co-suffer—she remembered a girl in high school who inspired her—”I never knew her name or anything about her but in a way she cast a light about her.” She also recalled a young Polish woman who reminded her of the Virgin Mary whom she met when she first went to Communion (a scene that appears in The Dispossessed). “How contemplation of that Polish girl deepened my faith!”[95] Could love ever be wrong? Without the grace of God, it could lead to temptation and temptation, but that was just as true, she argued, for any kind of love. “Unbridled sex, practiced today in every form or fashion,” was certainly worthy of censure, but love itself could only deepen understanding. “I mean that one must be grateful for the sate of ‘in-love-ness’ which is a preliminary state to the beatific vision, which is indeed a consummation of all we desire.”[96] She seemed to take a particular dislike to drugs, probably because they were unfamiliar, possibly also because they reminded her of her own drinking days, which embarrassed her. Maybe because both of those things were forms of escape from the sorrows of the world, but sorrow was suffering and suffering was love. It was only when she embraced suffering that she found joy. It had happened once, at the great moment of her conversion, and it continued to happen every day in moments of struggle. “To love is to suffer. Perhaps our only assurance that we do love God, Jesus, is to accept this suffering joyfully! What a contradiction!”

With grandchildren ca. 1958.

With grandchildren ca. 1958.

.

The Hard Work of Loving

While Dorothy worked out her ideas on feminism, women, sex, and love in her writing, she was also putting her ideas on charity into action. She viewed herself as a writer, frequently declaring that writing brought her the greatest joys in her life. But very little of her day was actually devoted to writing. It couldn’t be. She was the heart of a network that fed, clothed, and sheltered hundreds of people every day. The Catholic Worker was a unique organization in that it operated as a newspaper, a soup kitchen, and a shelter, all within the same few rooms. “The trouble with the CW is that one is so busy living there is no time to write about it.”[97] Dorothy and the other CW volunteers lived and ate alongside the alcoholics, the prostitutes, and the unemployed whom they sheltered. She wrote to support them as much as she did for personal fulfillment, and even then, she wrote only in moments stolen from brewing coffee and boiling soup for the lines of men and women that wove around the block even years after the Depression had ended, not to mention lending them a sympathetic and non-judgmental ear when necessary. She frequently found the latter task the greatest challenge. As she chronicled in her diaries, the poor can be incredibly unpleasant. They vomited in the stairwells, stole money for drugs, swore, cursed, and sometimes screamed late into the night. This indeed was the hard work of loving she wrote about. How to love the unloveable? She knew the answer—she had to see Christ in each one of them. But how difficult that was in practice. She admitted that at times she found the poor “repellant.”[98]How could you look into the dull eyes of an alcoholic or a schizophrenic raging in madness and see God inside them? How could you summon a vision of Christ when you dwelt in Hell? “. . . To be present, to be available to men, to see Jesus in the poor, to welcome, to be hospitable, to love. This is my need. I fail every day.”[99]

She was rarely rewarded, but the moments when she received gratitude must have been incredibly perfectly sweet. Edward Breen was an especially hard case who could and (should Dorothy’s canonization process prove successful) literally did try the patience of a saint. In 1935, she wrote to her friend Catherine, “Will you please pray real hard for a Mr. Breen who is at the present moment my greatest and most miserable worry? . . . He won’t be comfortable . . . and he, after all, is Christ.[100]” He yelled racist epithets at the staff and insisted he hated them all. But he stayed at the house until his death in 1939, and she persisted in her attentions to him. When she went traveling, she wrote him affectionate letters telling how proud she was of his improved behavior.

…..Dear Mr. Breen, This is but a note to tell you to be good and to be happy even though it means a great effort of will. I know you haven’t been feeling well, you poor dear, but take care of yourself, and try to keep calm and peacable in mind, and you will make me happy. I know things become very hard and disagreeable at times, but just offer it up for my intention.”[101]

And the difficult Mr. Breen was just one person of the hundreds she dealt with in the 1930s. Dorothy interacted with his equally stubborn sucessors every day until her death at eighty-three, because she never stopped living at the Catholic Worker shelter. Throughout those years, she frequently gave up even her room to people in need of shelter. She ate whatever they ate, however plain, and found her own clothes in the donation bundles so that she could devote her income to them. From her diary in 1944:

I darn stockings, three pairs, all I possess, heavy cotton, grey, tan, and one brown wool, and reflect that these come to me from the cancerous poor, entering a hospital to die. For ten years I have worn stockings which an old lady, a dear friend, who is spending her declining years in this hospital, has collected for me and carefully darned and patched. Often these have come to me soiled, or with that heavy hospital smell which never seemed to leave them after many washings. And the wearing of these stockings and other second-hand clothes has saved me much money to use for running of our houses of hospitality and the publishing of a paper.[102]

Perhaps because of my own love of new clothes, and perhaps too because I know Dorothy shared it, this passage affects me greatly. Whenever I face the hard work of loving, I think about Mr. Breen and the mended stockings and the sacrifices they represented for her. Dorothy’s anguish is my salvation, because if the woman who created the Catholic Worker Movement sometimes found people unendurable, how much hope is there for the rest of us!

Reading at the farm, ca. 1937.

Reading at the farm, ca. 1937.

Some of Dorothy’s writing disappoints me. I have wished I could write an essay about how her feminist convictions strengthened over time and only became more radical, in the commonly accepted sense of the word. That she strode seamlessly from New Womanhood to Women’s Liberation. I admire so much her refusal to live her life on any one else’s terms. To me, it is such a shame that she condemned her own courageous behavior as sinful and glossed over everything that didn’t fit into her Catholic moral narrative. She had defied convention by living with Forster Batterham without marrying him, yet later she conveniently decided they had been “common-law” married. That the “common-law” marriage was a later invention is made clear in letters from the 1920s when she described Tamar as his illegitimate daughter. It seems like she was a radical before the world was ready who then retracted by the time the world caught up with her. I suppose my acknowledgement of her faults is important because otherwise I would be limited to hagiography in writing about her. I would rather approach her as she was, which was human, and therefore, flawed. Even in her flaws, however, I find her appealing, because for all her harsh rhetoric, she was uniquely flexible in her ability to adapt, forgive, and accept. Her sister Della, who remained her best friend until the end of her life, worked for Margaret Sanger. Tamar’s marriage ended in divorce and she and most of her children rebelled against Catholicism, so that several of Dorothy’s great-grandchildren were born out of wedlock and most never baptized. Dorothy accepted all of these blows to her faith, sometimes with sadness, but never withdrawing affection. She continued to act as a loving mother and grandmother, supporting Tamar emotionally and financially. And remarkably, in the 1950s she reconnected with Forster and helped nurse his live-in mistress (he had stubbornly adhered to his anti-marriage stance) through cancer. What touches me most is a letter Dorothy wrote in response in 1973 to a young girl in distress because of an abortion:

I’m praying very hard for you this morning, because I myself have been through much of what you have been through. Twice I tried to take my own life, and the dear Lord pulled me thru that darkness . . . My sickness was physical too, since I had had an abortion with bad after-effects, and in a way my sickness of mind was a penance I had to endure.

But God has been so good to me—I have known such joy in nature, and work—in writing, as you must get in your painting—in fulfilling myself, using my God-given love of beauty and desire to express myself. . . .

Again, I beg you to excuse me for seeming to intrude on you in this way. I know that just praying for you would have been enough. But we are human and must have human contact if only thru pen and paper. I love you, because you remind me of my own youth, and of my one child and my grandchildren.

When I read how tenderly she responded to others, I realize that she reserved her harshest criticism for herself and that the only sins she refused to forgive were her own.

In complicated situations, I actually do ask myself, what would Dorothy do? I don’t mean this in a sentimental way and I certainly don’t think she was perfect or would have all the answers even could I magically commune with her. I ask this question precisely because I know that she was flawed and that she understood imperfection to be the human condition. When I waver in faith or love, I think she would tell me to forgive the flaws in my fellow humans as well as myself and to treasure those flaws as the mark of the divine. A friend of mine, in the process of an unpleasant divorce, told me he had begun to forgive his wife for her years of cruelties, because he started to recognize aspects of her in his daughter, whom he loved wholeheartedly. If he loved the weaknesses of one, how could not love them in the other? Our flaws stem from our creator, and if we love him we must love his designs, which is to love each other. “The final word is love,” Dorothy declared, over and over, in articles and letters. She loved with passion, a habit she could never cast off. “We should be fools for Christ,” she also wrote frequently. Dorothy formed a foolish and passionate love wide enough to embrace the entire body and creation of God. She loved the poor, the tormented, the almost unloveable. She even, bless her heart, loved the non-believers, which includes myself. “For those who not believe in God—they believe in love.” I don’t know if I believe in God but I know I believe in Dorothy—her message, her words, her acts of charity in a dark world.

.

Works Cited

Bauer, Dale M. Sex Expression and American Women Writers, 1860–1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2009. Print.

Boulton, Agnes. Part of a Long Story: Eugene O’Neil as a Young Man in Love. New York: Doubleday, 1958. Print.

Boyce, Neith and Hapgood, Hutchins. Intimate Warriors: Portrait of a Modern Marriage, 1899–1944, Selections by Neith Boyce and Hutchins Hapgood. Ed. Ellen Kay. Trimberger. New York: The Feminist Press, 1991.

Coles, Robert. Dorothy Day: A Radical Devotion. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press, 1989. Print.

Costello, Virginia. Revolutionizing Literature: Anarchism in the Lives and Works of Emma Goldman, Dorothy Day, and Bernard Shaw. Diss. Stony Brook University, 2010. Print.

Day, Dorothy. Dorothy Day. The Dispossessed. 1932. Series D-3, Box 1. Dorothy Day-Catholic Worker Collection. Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI.—. The Duty of Delight. Ed. Robert Ellsberg. New York: Image Books, 2008.

—. The Eleventh Virgin. New York: Albert and Charles Boni, 1924.

—-. From Union Square to Rome. (New York: Orbis Books, 2006). Print.

—-. The Long Loneliness: The Autobiography of Dorothy Day. New York: Harper and Row, 1952. Print.

—-. On Pilgrimage. Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1999. Print.

—-. “Reflection during Advent—Part Three, Chastity.” The Catholic Worker 10 December 1966.

—-. Therese: A Life of Therese of Lisieux. Springfield: Templegate Publishers, 1960. Print.

Dearborn, Mary. Queen of Bohemia: The Life of Louise Bryant. New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1996. Print.

Eastman, Crystal. On Women and Revolution. Ed. Blanche Wiesen Cook. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1978. Print.

Falk, Candace Serena. Love, Anarchy, and Emma Goldman. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press, 1984. Print.

Fisher, James Terence. The Catholic Counterculture in America, 1933–1962. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1989. Print.

Forest, Jim. All Is Grace: A Biography of Dorothy Day. Maryknoll, NY: Orbis Books, 2011. Print.

Gillette, Meg. “Modern American Abortion Narratives and the Century of Silence,” Twentieth Century Literature 58:4 (2012) 663–687. Academic Search Premier. Web. 5 March 2015.

Goldman, Emma. Living My Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, Inc., 1931. Print.

Hemingway, Ernest. Selected Letters 1917–1961. Ed. Carlos Baker. New York: Scribner, 1981. Print.

LaBrie, Ross. The Catholic Imagination in American Literature. Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1997. Print.

Miller, Nina. Making Love Modern: The Intimate Public Worlds of New York’s Literary Women. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999. Print.

Piehl, Mel. Breaking Bread – the Catholic Worker and the Origin of Catholic Radicalism in America. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1982. Print.

Rosen, Ruth. The World Split Open: How the Modern Women’s Movement Changed America. New York: Penguin Books, 2000. Print.

Stansell, Christine. American Moderns: Bohemian New York and the Creation of a New Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000. Print.

.

Laura Michele Diener teaches medieval history and women’s studies at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. She received her PhD in history from The Ohio State University and has studied at Vassar College, Newnham College, Cambridge, and most recently, Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her creative writing has appeared in The Catholic Worker, Lake Effect, Appalachian Heritage,and Cargo Literary Magazine, and she is a regular contributor to Yes! Magazine.

Jane Austen by her sister Cassandra, c. 1810. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

Jane Austen by her sister Cassandra, c. 1810. Courtesy of Wikipedia.

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.