In the summer of 2014, I spent two weeks with friends in Bosnia-Herzegovina. At the time Sarajevo was marking the centennial of the assassination that sparked World War I, the national soccer team was making its first appearance in the World Cup, and the nation was reeling from massive citizen protests in the winter and devastating floods in the spring. My host and guide was the Bosnian writer Goran Simić. —Thomas Simpson

x

I. Sarajevo, June 20, 2014

Like an existentialist’s bad joke, Goran Simic’s driveway sits on a dangerous curve. The circular, convex mirror posted across the street, where the sidewalk is, helps only so much. All it tells you is whether a car is bearing down on you, right now, from the left. Once you make your move, all bets are off. The best you can do is utter a prayer, or mutter a curse, before you lurch into the unknown.

Alone, on foot, I make it safely to the other side. My pulse races, but I still can’t shake the jetlag as I start the twenty-five minute walk south into the heart of Sarajevo, down the wide, busy streets called Patriotske Lige and Koševo. Thick, gray morning clouds shroud the city, and the weak daylight throws shell-shocked buildings and roadside litter into dismal relief. A little of the Bosnian I’ve been studying for months comes to mind: meni se spava, I feel tired. God, I feel tired. I barely slept on the overnight flight across the Atlantic, an hour maybe, two at the most. In my sightline, two rows ahead, a guy was watching The Wolf of Wall Street on his seatback screen. I dozed in and out of that three-hour marathon of excess: stockbrokers manhandling strippers, Jonah Hill masturbating openly at a lavish pool party, Leo DiCaprio snorting cocaine off an eager blonde’s heaving breasts.

So I am waking up slowly to Sarajevo, even though the visuals are jarring. I see the hulking, worn stadium from the 1984 Olympics, a glaring reminder of Yugoslavia’s depleted prosperity and promise. I clutch my black backpack’s single, diagonal strap, which stretches like a seat belt from my left shoulder to my right hip. The knuckles of my right hand bore under the strap into my sternum, as if to knead my constricting heart and lungs. I lift my chin and flex my shoulders, chest, and biceps a little. I’m feigning toughness, copying the confidence of younger, streetwise Bosnian men.

I’m steeling myself because there’s more to take in: three massive, historic urban cemeteries, Muslim, Catholic, and Serbian Orthodox. Locals say the bones of the assassin, Gavrilo Princip, are here in a little roadside Serb chapel. Soon Serb nationalists will adorn it with flowers, marking the assassination’s centennial by salting the wounds of neighbors who managed to survive the Siege. “Gavrilo,” a hit song by the Bosnian rock band Zoster, captures the mood. It’s got the looping, centripetal feel of an anthem and a hangover:

Gavrilo, Gavrilo, srce uzavrelo…

Gavrilo, Gavrilo, raging heart…

za jedne on je heroj, a drugima je zločinac…

to some he’s a hero, to others a criminal…

na put bez povratka, on je krenuo…

he took off on a path of no return…

još i danas hodimo njime.

and we’re still walking it today.

I had anticipated some the graveyards’ lessons about World War I, World War II, and the Siege of Sarajevo. The headstones from this century are somehow more unsettling. An unwelcome thought intrudes: Sarajevo will go on dying. A few steps later, what feels like a corollary follows on its heels: None of this is going to work. Multi-ethnic Sarajevo and Bosnia-Herzegovina. The International Community. Democracy. Human Rights. None of it, despite the lessons of history, and despite the gala centennial events to come next week, when the eyes of the world will once again, however briefly, be on Sarajevo.

Cemetery in Sarajevo

Cemetery in Sarajevo

I don’t know where I’m headed except a café somewhere to find coffee and my bearings after two years away. I pass a side street named after the poet Šantić and a bakery called Markale, where my mind involuntarily adds “massacre.” I’m getting closer to the action now. Off to my right, on the main thoroughfare that honors Tito, I see the stately national presidency building, a monument to the idiocy and greed of Bosnia’s corrupt, ethnonationalist ruling elites. Just last February, protesters torched it, taking their cues from Tuzla in trying to kickstart a “Bosnian Spring.”

A spacious café and bakery, brightly lit, mercifully intervenes. I go in, merge with the morning rush, and scan the large glass case of pastries. When it’s my turn, I fumble through my Bosnian. Dobro jutro – “Good morning” – I say. Želim kafu…espresso, i… – “I’d like an espresso and….” My Bosnian suddenly leaves me. I can’t remember the word for pastry, much less any kind of fruit. As I start to gesture clumsily toward a tray of turnovers, a woman behind me steps in and saves me. Višnja, she says – cherry – and laughs.

I thank her – hvala – placing my relaxed right hand softly over my heart. I take a window seat, a few feet above street level, and watch Sarajevans stream into the city in cars, on buses, and on foot. I write višnja in my notebook and practice the ice-breaker that I’ll use over and over again on this trip: Na bosanskom, govorim kao beba. In Bosnian, I talk like a baby.

When my espresso comes, I pour in the two thick packets of sugar that come standard. They render the bitterness palatable, the darkness soothing. As if on cue, the sun pierces the clouds. I end up staying for hours, reading Hemon’s The Book of My Lives, jotting down fragmented thoughts, and ordering a second espresso. Meni se spava, I tell the waitress with a wink. She laughs, understanding, and suddenly I remember what makes Sarajevo such an easy target. So much life, compressed and distilled, to destroy from above. I size up the huge pane of glass to my right, remembering how desperately Sarajevans avoided and barricaded their windows during the Siege. I imagine how easily the wall of glass could shatter, and I start to hope, stupidly, irrationally, that this café will always be here, safe, forever.

§

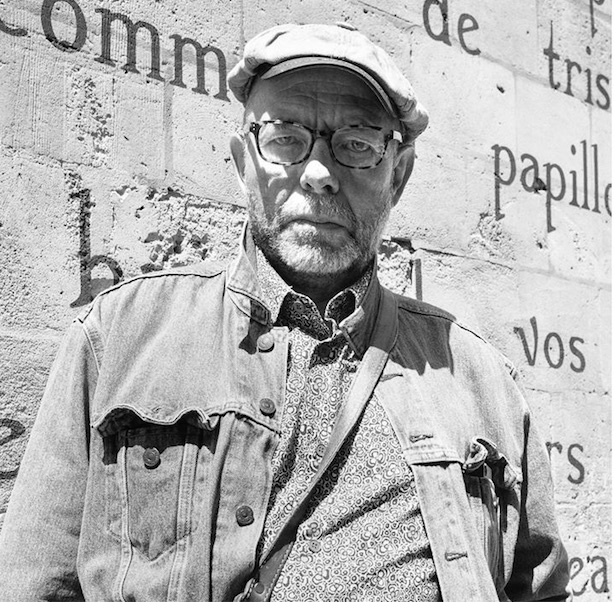

A lunch date with the poet Goran Simić pulls me away. We’re headed up to a small log-cabin restaurant near the Skakavac waterfall, about a thousand meters above Sarajevo. In his aging two-door black Renault, we inch and wind up suspension-mangling dirt roads. When we’re finally in the clear, we step out, glance miles across the valley, and find a patio table in the sun. The restaurant’s owner, Dragan, likes to joke that the daily menu is whatever he’s got. You have to trust him, and here one’s faith is rewarded. He assembles a succulent assortment of fried dough, local cheeses, sliced fresh tomato, and smoked sausages. Goran and I drink a little local rakija and beer.

Goran is back in Sarajevo after more than fifteen years in Canada, where he resettled after the Siege. Goran’s acute sense of how much work needs to be done in Bosnia has brought him home. His labors of love are the Bosnian plenums – grassroots, democratic citizen assemblies fighting for political reform and social justice – and PEN Bosnia-Herzegovina, a local chapter of the international literary organization that celebrates the freedom of expression as a human right. This Bosnian branch of PEN emerged during the Siege, when Goran and some colleagues created a downtown haven for writers desperate for a meal and place to write. Now, as the multiethnic organization’s membership ages and carries out its work without support from the Bosnian government, the challenge is to keep the society alive and infused with fresh blood. It’s an ongoing experiment, a test of whether an inclusive humanism can triumph over death-dealing ethnonationalism. Yesterday brought a small victory: the induction of new members, including two brilliant young women, Adisa Bašić and Šejla Šehabović. Yet the meeting took place in the midst of a bitter internal struggle, a war of words between Goran and a dogged literary rival who keeps publicly calling Goran a Chetnik, a bloody Serb – not one of us, not a real Sarajevan. The conflict threatens to tear the Bosnian PEN apart.

Restaurant near Skakavac waterfall

Restaurant near Skakavac waterfall

After the meal, Goran finds a picnic bench where he can stretch and sack out in the shade. He says his battery’s exhausted, and Skakavac is his place to recharge. I can see why. The sun is strong, the mountain air clean. Grasshoppers chirp, sheep bleat, the bells of livestock tinkle, and a creek sings below. I walk a little farther up the hill, taking photographs of the panorama. I nap briefly in a small hikers’ shed. Rain clouds invade and threaten but move on. There is peace.

§

Eventually it’s time to get back to the city for an evening poetry reading. Sponsored by the Mak Dizdar Foundation, and held in a gorgeous upper-floor atelier with exposed brick and candlelight, the affair is intentionally international. It gathers award-winning writers from Bosnia-Herzegovina, Croatia, Serbia, and Montenegro. Goran’s friend and PEN colleague, the poet Ferida Duraković, is the M.C. Performing live alongside her is one of the finest lutenists in the world, Edin Karamazov. They are mesmerizing together.

To the audience’s left is a balcony with French doors. It offers a sunset view of the Presidency Building, highlighting the difference between the politics and the poetics of Bosnia. To our right is a bar with hors d’oeuvres, and members of the audience move back and forth freely throughout the evening. The atmosphere invites us to linger, and we do for more than an hour after the reading ends. I wander onto the balcony and gaze at the Sarajevo night sky.

A thunderstorm hits and brings heavy rain. I go back into the atelier and meet two adult grandsons of Mak Dizdar, the celebrated Yugoslavian poet. I tell them that tomorrow I’ll be off with Goran to Stolac, their grandfather’s birthplace, southwest of Sarajevo. The Dizdar brothers give me a sense of what I’m in for: a breathtaking landscape and an ancient city, with extraordinary Ottoman architecture that’s been utterly razed.

.

II. Aladinići and Stolac, June 21-22, 2014

The next morning we drive southwest to the Herzegovinian village of Aladinići to celebrate the birthday of Adisa Bašić, one of the writers who has just been inducted into PEN Bosnia-Herzegovina. In her mid-thirties, blonde, and tall, she towers over many of the older, predominantly male colleagues who voted her in. On the way out of town we pick up Hana Stojić, a Sarajevan friend and contemporary of Adisa who works as a literary translator in Berlin.

The rural, hilltop Aladinići property feels worlds away from Sarajevo, where Adisa still has an apartment in a decaying high-rise. It’s in wine country, the climate Mediterranean. A grape arbor shields the front patio and driveway from the summer sun. Peaches, cherries, watermelons, apricots, grapes, pomegranates, figs, and mint grow nearby. Here, Adisa has found refuge and rejuvenation. One of her dreams, she says, is to gather generations of Bosnian women artists in a place like this for retreats, so they can tell and write their stories.

After hours of relaxed conversation and a dinner of grilled chicken and ćevapčići, we get down to business. Bosnia’s national soccer team, making its first appearance in the World Cup, has a match against Nigeria tonight in Brazil, and we’re all dying to watch. Adisa and her husband, Adnan, tack a big Bosnian flag to the front of the house, and some neighbors join Adnan in an attempt to rig a TV up on the patio. They take turns fiddling with the controls and climbing onto the one-story cottage’s flat, cement roof to get to the antenna. As the sun sets, Johnny Cash’s “Ring of Fire” pumps out of the stereo in Goran’s car, parked under the vine arbor with the doors open. The music’s unruly passion mingles with the village’s evening call to prayer.

Goran, Hana, and I plan to crash at a hostel in Stolac after watching the midnight match at Adisa’s. But as darkness comes the owners call to encourage us to come sooner rather than later. They tell us that the police are already patrolling Stolac’s main intersection in case there’s trouble with the crowds, and the last thing we’d want to do is stumble through town in the middle of the night. So we say good night – laku noć – to our friends and leave Aladinići.

On the way to Stolac, Goran and Hana ride in front and sing along with Johnny Cash. They’re nailing it, conjuring the voice of the man in black, the vocal cords torn but smooth: I’m gonna break, I’m gonna break my, gonna break my rusty cage and run.

We find the hostel banked on a steep riverside hill. As we settle in, Goran and Hana step onto the balcony for a smoke (one of the reasons they’re so good at imitating Cash). I join them at the rail, stargazing. Below us, the dammed Bregava River rushes, soothing and strong.

Close to midnight, Goran and I get ready to go into town to watch the game. Hana, exhausted by a spate of recent travel for work, bows out and sleeps. As Goran and I drive across the Bregava and approach the main intersection from the north, we see disturbing signs: on our right, the lampposts sport Croatian flags, not Bosnian. On our left looms the religious equivalent of the flag: a Catholic church’s enormous bell tower, aspiring to dominate the surrounding landscape.

Sure enough, the cops are set up at the intersection, standing outside their parked, flashing cruiser. I start wondering what we might be getting ourselves into. But after we park and start to walk, excitement trumps the tension. Bosnian flags hang high across this southern stretch of road like fluttering Buddhist prayer flags, and the first bars we see with outdoor patios are jammed. We gravitate to one across the street that has a little more breathing room. We quickly figure out why. The bar’s television isn’t showing the game. The choice needs no translation. This is a Croat bar. Who gives a shit if Bosnia’s playing tonight?

We walk back across the street. A kid tosses a firecracker onto the pavement just a few feet away from us. BANG! I shudder and swear before laughing nervously and moving on. Goran and I spot a little table with two chairs at the edge of a sprawling patio, where we can see most of the huge outdoor video screen. A waitress comes over to greet us. She’s lean and radiant, with shoulder-length brown hair and a small tattoo on the right side of her neck. She’s wearing the royal blue jersey of Edin Džeko, the Bosnian striker who’s a bona fide superstar in the English Premier League. Džeko grew up in Sarajevo, survived the Siege, and has become the kind of once-in-a-generation player who is giving Bosnians faith that this team can make a deep tournament run.

After Goran and I order our drinks, I use a clumsy mix of Bosnian and English to ask the waitress for the wi-fi password. She smiles and switches to English on the fly: l-o-c-c-o, the name of the bar, all small letters. I connect, and right before the Bosnian national anthem I send my wife pictures of Aladinići, of pomegranate, oleander, and the grape arbor. I tell her there’s a chance that the adjacent property could be for sale, that Goran and I are starting to dream like Adisa. Something like a writer’s colony, a place for Goran and other Bosnian artists to get away for more than an occasional afternoon at Skakavac.

The game’s about to start. This is one that Bosnia desperately needs to win, or at least play to a draw, to advance beyond the opening round. In the first match of the tournament they had given mighty Argentina all it could handle, but a fluke own goal and some late wizardry by the Argentinian Lionel Messi – some say he is the best in the world – sealed the Bosnians’ fate, 2-1. It was an inspired, impressive performance by the Bosnians that left them with no points.

In tonight’s first half, the favored Bosnian team looks strong. They sustain pressure on the Nigerian defense. Before long, Džeko breaks free, and his shot finds the back of the net. We erupt, bolting to our feet and pumping our fists before the heartbreak: Džeko is called for being offside. The goal is nullified. Replays confirm that it was a terrible call. Just minutes later a Nigerian forward, fighting for space, pushes a Bosnian defender aside and scores. No foul is called. Just like that it’s one-nil, Nigeria.

At halftime we’re keeping hope alive. The waitress stands poised where the patio meets the bar, her chin raised a little as she surveys the crowd and grooves to the driving rock music. Goran and I find a table at the center of the action, in the thick of the crowd, with a better view of the screen.

When the second half starts, Džeko’s off his game, getting free and finding chances but not striking cleanly. Our spirits lift when Vedad Ibišević, who scored against Argentina, enters the match late, but the team still can’t find a way to break through. Tension mounts. Bosnia’s running out of time. Right behind us, a fan’s drumming, which has been keeping us upbeat all night, is now accompanied by somebody’s drunken vuvuzela. Hoarse, blaring, and erratic, it’s driving us insane. Two powerfully built guys in front of us finally snap, turning around and yelling at him in Bosnian to – I can only assume – shut the fuck up. As the clock mercilessly advances, one of them starts to sidestep us and move toward the vuvuzelist. I start looking for escape routes, trying to figure out if Goran and I can get back to the car and out of town if fists and bottles start to fly. I’m not sure we can. A reassuringly tall, formidable bartender steps in, however, and cooler heads prevail.

The clock hits 90:00. Only a few minutes of extended, injury time remain. Džeko suddenly finds a seam, an opening to the keeper’s right, but his shot is deflected and caroms off the left post. It’s crushing. Bosnia is finished. When the final whistle blows, a bottle shatters on the pavement behind us. I flinch, fearing a swell of rage, but it doesn’t come. We leave in peace. Goran quickly musters perspective. The team just had no energy tonight, he says. We find the waitress, settle the tab, and make our way to the car.

We get back to the hostel on the Bregava after 2 a.m. Hana stirs from a deep sleep and asks how the match came out. We give her the bad news. In the morning, forgetting, she asks again. We go into town for coffee, settling at a café next to Locco. Hana tells me to take my camera and walk over to the nearby mosque, undergoing major restoration, to see a rare neighboring of olive and oleander trees. I walk the neighborhood a little in broad daylight. I get my first good look at the Bregava and the surrounding hills that frame the architecture of nationalism: the rival sanctuaries, flags, bars, and monuments.

Before we leave town I walk past Locco. I see our waitress sitting outside on the empty patio. She looks pale and spent. We exchange polite, flat smiles. As the day wears on, Bosnians will rage about the officiating, citing the blown calls and a photograph – of the head referee, Peter O’Leary, smiling at the end of the match with his arm around a Nigerian player – that looks damning. Tens of thousands of Bosnians will sign fruitless online petitions demanding the suspension of O’Leary and even a revision of the score to make the final score 1-1. When we get home to Sarajevo, a newspaper features a photograph of a dejected Bosnian in Brazil. The headline reads, “TUGA NAKON EUFORIJE” – heartache after euphoria, the euphoria of feeling, at least for a little while, that anything is possible.

Goran Simić relaxing at Aladinići

Goran Simić relaxing at Aladinići

.

III. Mostar and Blagaj, June 25-27, 2014

Goran and I had been corresponding all spring about driving to the Adriatic Coast, which I’ve never seen. We finally have a plan. We’ll head southwest from Sarajevo. On the way we’ll spend the night in Mostar with friends of mine, Lejla and Sasha, and their children, Ena and Sandro. Lejla and I had engaged in the standard bilateral negotiations about food and lodging. I said that Goran and I didn’t want to impose, so we would take them out to dinner and spend the night in a hotel. Lejla wondered what the hell I was thinking. We’ll cook out, she said, and watch the Bosnia-Iran World Cup match. You’ll stay in Ena’s room. We’ve got room for Goran too.

When we arrive, we call Lejla from the riverside patio of the stylish, renovated Hotel Bristol, where I had stayed in 2004. We meet and embrace on the bridge over the Neretva.

Ena, who’s eleven now, has her room ready for me upstairs, with its view of conjoined apartment rooftops and the neighborhood minaret. In neat rows images of cartoon princesses and professional rock climbers plaster the walls. I remember watching Ena compete as a climber two years ago, and a framed certificate reveals that she is now a youth national champion. Two-year-old Sandro has turned into a powerhouse too. We tussle playfully, and when he kicks my leg with surprising force, I start thinking that Bosnia might have its next Džeko.

I find Sasha outside by the grill. We’re meeting for the first time. When I visited the family before with my guide – Lejla’s cousin and Sasha’s best man – Sasha was in Norway, installing air conditioners to help support the family. In his mid-thirties, he’s of medium height and wiry, like Ena, but weathered, with buzzed brown hair, piercing eyes, and an iron jaw. With him is a friend, Slađo, whom I’ve met before. Tall and thick, like the Yugoslavian forwards who occasionally appear in the NBA, he has an infectious laugh. As soon as I see him, I remind him of the night we drove up a steep hill on Mostar’s perimeter. When we got out of the car, Slađo sighed and surveyed the quiet basin. He seemed poised to impart wisdom. He said, “You know, Mostar is just a giant toilet bowl that needs to be flushed.” People in every former Yugoslavian republic might have heard us laugh that night.

As he minds the chicken on the grill, Sasha shares fragments of his story. As a high-school-aged kid, he lost his father in the war. After that, he had spent a little time in the US, first at an international youth camp, Camp Rising Sun in upstate New York. Then he stayed briefly with Frank Havlicek, an instructor in international affairs at American University who had visited Bosnia and knew Sasha’s mother. Sasha tells me that Havlicek offered to set him up with a mailroom job at The Washington Post, a basement apartment, and a car, but Sasha turned him down. He says he couldn’t ever get used to the States. The people were too cold. They didn’t know their neighbors. They would look strangely at you if you just tried to bum a cigarette. A couple of times he snapped and got into fights. He knew he had to come home.

The food’s ready, so we go in for dinner and the game. Bosnia decimates Iran, 3-1. Nigeria will advance with Argentina to the second round. We talk late into the night.

The next morning, I’m the first to rise with Ena and Sandro. I ask Ena if she can show me how to connect to the internet. It’s not self-evident because the family laptop is missing some keys. Ena points to the culprit, Sandro, and laughs. To buy ourselves some time on the computer, we bribe him with my pen and let him scribble with abandon in my notebook.

After a few minutes of sending quick messages home, I sign off and grab my Bosnian-English phrasebook. Ena, who has studied English in school, is game. We practice:

Yesterday was Wednesday.

Jučer je bila srijeda.

Today is Thursday.

Danas je četvrtak.

Tomorrow is Friday.

Sutra je petak.

Ti si moj učitelj, I say – You are my teacher. She smiles, ear to ear.

Goran, Lejla, and Sasha make their way down. As Lejla brews coffee, they talk freely in Bosnian at the table. I stay with Ena, continuing my language lessons. Suddenly the conversation grows animated. I ask what’s up, and Goran tells me that a local youth – briefly in jail for savagely beating a Mostar university economics professor, Slavo Kukić, with a wooden bat – has been released and apparently will not face trial. Kukić had made the nearly fatal mistake of questioning the judgment of some fellow Bosnian Croats who gave a hero’s welcome to a convicted war criminal, Dario Kordić. Kordić had recently been released from prison after serving only two-thirds of a twenty-five year sentence for crimes he committed during the ethnic cleansing of Ahmići in 1993. The news leaves Goran, Lejla, and Sasha stunned.

I thank Ena, freeing her for morning cartoons on TV. I go to the table. Knowing that Goran and I will have to leave soon, I ask Lejla what sort of future she sees for her family in Mostar, what sort of future for Ena and Sandro. She is blunt, needing none of her usual time to switch to English. “There is no future in a divided city,” she says.

Lejla sends me off with a gift for my family, a set of four ceramic mugs decorated with Mostar’s Old Bridge. Despite my best efforts to pack them carefully, two will shatter somewhere between here and home.

§

We have one last stop on the way out of town: a second round of coffee back at the Hotel Bristol with Štefica Galić, a journalist and human rights activist based in Mostar. A Bosnian Croat, she’s been visiting Slavo Kukić in the hospital. She corroborates our pessimism. “There is no justice,” she says. “Nothing will happen. We know that for sure.”

The beating took a heavy toll; images of the professor with a bandaged skull, blood-soaked shirt, and battered back are circulating widely. “He will feel that pain his whole life,” Štefica tells us, “but that will not stop him.” She knows what she’s talking about. She has been physically assaulted by Croat nationalists before, after screening a documentary about her late husband, Neđo, who had risked his life during the war to save a thousand neighbors from ethnic cleansing. Some call him the Bosnian Schindler.

Now, in postwar Mostar, Štefica carries on with what she sees as a struggle against resurgent fascism. Even some of her relatives have begged her to be quiet, to quit stirring up trouble, but Štefica is fit for battle. A generation older than I am, she is in better physical shape. She has the lean physique and perfect posture of a yoga instructor. Her bright blue eyes shine past carefully penciled mascara; they are reservoirs of compassion and sorrow.

I tell her in Bosnian that I have a question, a serious one: do you want to stay or leave? She says she’ll stay, of course. So much of her life, so much of her family, is here. But sometimes, she says, “I want to disappear.”

Like Lejla, Štefica sends me off with souvenirs of the place she loves, the place she wants me to remember: a ceramic memento of the Old Bridge and a travel guide that convincingly portrays Herzegovina as “an inspiring piece of Heaven.” Even so, I can’t help feeling that Štefica – and Mostar – are in a hellish limbo between recent and imminent devastation. As Goran and I head south out of town, I see scrawled Bosnian graffiti that for once I have no trouble translating: nema boga, there is no God.

§

Sorrow and fear have me dazed. Wisely, Goran has planned some time for us at the wellsprings. We’ll have lunch in Blagaj at the source of the Buna River, which emerges clear and abundant from beneath a high, sheer cliff.

At the base of the cliff, an old Sufi dervish house, neglected during the war but recently restored, offers a chance for quiet contemplation. Riverside, a framed passage from the Qur’an reads, “We made every living thing from water.” As Goran and I dip our hands in the river, he tells me that the Buna has somehow always had a way of maintaining its equanimity even during the recent floods.

We cross the small bridge to eat fresh trout and Vienna schnitzel. After taking a few photographs, we walk the narrow road, lined by souvenir stands, back to the car. Suddenly Goran is leaning through a passing van’s window. He’s nose to nose with the driver, and I have no idea what has set him off. Then I hear peals of laughter, and Goran lets me in on the joke. The driver is his old buddy Ermin Elezović, who’s here with his wife, Alma, on their day off from leading guided tours all over the country. We head back to one of the restaurants for coffee and dessert. Alma insists I try Ashura, a delicious Turkish pudding that blends apple, figs, and nuts. Lore links it to Noah’s Ark, to miraculous survival during a time of famine and flood.

Ermin is candid: we’re crazy to drive to the coast today. The traffic, he says, will hold us up for hours. Improvisation ensues, and before long it’s settled: forget the coast. We’ll spend the night here, in Blagaj, with Alma and Ermin.

We go to their serene property, which they’ve just bought after spending most of their lives in Mostar, including the war years. The backyard, bisected by a stone path, extends to the Buna. In her garden Alma grows assorted herbs and vegetables. In the rest of the yard she and Ermin tenaciously plant, water, and prune.

It turns out that Alma and Ermin have known Sasha’s family for decades. They tell me something Sasha hadn’t, that his father was killed by a sniper – no, a grenade. (“What’s the difference?” Goran wonders aloud.) At the time their own son, Jasmin, was just in elementary school. Inside the house Ermin shows me wartime black-and-white photographs of the family. Pointing to little Jasmin, who at the time had been stuck indoors for six months, Ermin says, “Look at his eyes. The light is missing.”

In one shot Ermin wears a T-shirt from War Child International, the UK charity he worked for during the war. Through their mobile bakery, Ermin tells me, they made and delivered 1.3 million loaves of bread to trapped, terrorized people in Mostar. War Child also organized a star-studded British benefit album featuring Paul McCartney, which raised more than a million pounds to establish Mostar’s interethnic Pavarotti Music Center.

We have dinner on the covered patio: potatoes with garlic and herbs, a tomato and cucumber salad, plums, pears, strawberries, and cheese. At dusk, by candlelight, we drink from teardrop flasks of rakija. Lightning flashes across the western sky. A jolt of thunder follows. Goran, laughing, says it’s war again.

Alma says she finds herself thinking more and more about writing her story. The memories have been too much to live with this long, too much to bear. “I think I will be stronger,” she says. Goran encourages her. “Each single life is a novel, yeah?” he offers tenderly.

Before bed we watch some of the World Cup. Ermin pours me a shot of industrial strength Montenegrin rakija, 50% alcohol by volume. When I finally muster the courage to bring it slowly to my lips, it burns my eyes. I take two hesitant sips and start to cough. Goran and Ermin are in hysterics. I finish, say good night, and go up to the loft. Fresh air flows freely. It’s the best night of sleep I’ll get in Bosnia. Ermin must have known that to relax, I needed to be knocked out cold.

In the morning Jasmin comes by just as Goran and I are getting ready to leave. He’s 26 now, and the light is back in his eyes. He’s funny as hell, just like his parents. Telling him my name gets us riffing on The Simpsons. Jasmin’s favorite moment is of Homer adrift: “I’m not normally a praying man, but if you’re up there, please save me, Superman!” We cackle.

On the way back to Sarajevo, Goran and I find that Ermin has cut a piece of glass from his workshop to replace our cracked passenger side mirror. A few hundred yards down the pockmarked road, it pops out. We laugh, stop in the middle of the road, and reinforce it with duct tape. It holds the rest of the way.

Near Mostar we see more of the architecture of aggression: a brand new Catholic church, right next to a destroyed abandoned house. It’s a scene I’ve witnessed far too often. Homes and factories lie in ruins, while new, expensive sanctuaries grow like weeds. It’s the engineering and manufacture of cultural domination. Štefica called it pure provocation, like animals marking their territory.

Nature offers another brief reprieve. We wind north through the Neretva valley, farther and farther from the river’s end in the Adriatic Sea. Compressed strata of steep, forested stone slant sharply to the river at forty-five degrees before they gradually recline to parallel. Johnny Cash sings, If I could start again, a million miles away….

.

IV. Sarajevo, June 27-29, 2014

It’s the eve of the assassination’s centennial. Sarajevo’s commemorations have begun, and Goran and I go a little off the beaten path to one of our favorite spots, Sarajevo’s Museum of Literature and the Performing Arts. Two years ago, walking the city, I had wandered into the museum’s beautiful, landscaped courtyard of roses and stone pathways.

The museum’s director, Šejla Šehabović, like countless custodians of culture in Sarajevo, works for little or no pay, thanks to the wrangling of politicians who withhold appropriations from institutions that benefit all Bosnians, not just a single ethnic group. She puts on an incredibly brave face. In her thirties, with short brown hair dyed to a brilliant copper, she fights like mad to keep the museum alive. Last spring’s heavy rains brought fresh worries: a leaking roof threatens the papers of Ivo Andrić, perhaps Yugoslavia’s most famous writer, winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1961. His historical novel The Bridge on the Drina all but foretold the horrors to come at century’s end.

Šejla Šehabović and Goran Simić

Šejla Šehabović and Goran Simić

The mood is festive tonight. We’re here for the release of graphic novelist Berin Tuzlić’s Sarajevo Assassination 2914. Images from the book, enlarged to poster size, line the gallery walls. Menacing and dystopian, they evoke the present. Rival religious and ideological factions posture and provoke. They brandish cartoonishly violent mentalities in a restricted palette of aggressive red, black, blue, purple, yellow, and orange.

In the courtyard after darkness falls, live music and large-screen projection bring the book and exhibition to life. An earnest baritone narrates the novel’s text while a keyboardist and Tuzlić himself, a rock-solid drummer, add a dark, driving musical overlay. One of the text’s refrains distills centuries of manipulation and disillusionment: Istorija je fikcija, history is fiction.

§

The next morning, the day of the centennial, Goran’s in the mood to get back to Skakavac. The Vienna Philharmonic’s concert tonight at Vijećnica, the restored city hall and national library, barely interests him. He can take only so much reminiscing. He remembers racing to rescue what he could from the flames of that dying treasure. Ninety-eight per cent of the historic collections are lost forever. My own memory leaps to Goran’s “Lament for Vijećnica”:

When the National Library burned for three

days in August, the town was choked with black

snow. Those days I could not find a single pencil

in the house, and when I finally found one it did

not have the heart to write. Even the erasers left

behind a black trace. Sadly, my homeland burned.

When we settle at Skakavac, under another spectacular summer sky, we speak of Goran’s fresh collection of poems. “I am trying to put on paper something I would like to forget,” he says.

That afternoon and evening, Goran reconnects with friends. I’ve decided to mark the anniversary by walking the city. Crowds and sun lighten the mood. A store called “Marx™: Clothes for the People” welcomes tourists to post-socialist Sarajevo, and T-shirts of passing teens borrow English slang to indulge in urban sarcasm and play: “Slam Dunk,” “Fuck the Future,” “Cute But Psycho,” “I’m Limited Edition.”

In the centuries-old Ottoman bazaar I stop at the expansive courtyard of Bey’s Mosque. I circle and photograph the tall, canopied fountain. Without thinking, I place my left hand, palm and fingers, on one of its aged wooden pillars, and I’m nearly brought to tears. The wood feels alive – I almost know it’s alive – cool to the touch, and strong, but without the rigidity of stone. I breathe in slowly and am at rest.

To the east is the restored Vijećnica. It’s cordoned off for the exclusive, black-tie affair inside, but I can take photographs and listen to the concert’s simulcast outside at sunset, just across the Miljacka River. When hunger sets in, I set my sights on one of my favorite burek shops, and I decide to practice my Bosnian. Everything goes smoothly except for the math. Focusing on the two types of pie I want – beef and spinach – I lose all sense of proportion. I accidentally order a kilo of each, and the shop owner wonders if I’m certifiably insane. When I finally figure out what’s happening, I sheepishly confess, Trebam vježbati moje… – “I need to practice…” Before I can say moje broje (“my numbers”), the shopowner finishes the sentence for me: “…your Bosnian?” I turn red and laugh, perfectly content to exchange my dignity and a few bucks for some of the best food in Sarajevo.

At nightfall, a heavy boom shakes the city. It unnerves me, and it takes me a few seconds to hear the sound for what it is: a celebration of the end of the day’s Ramadan fast. A swell in the market crowds follows. I linger at the outdoor cafés before walking home close to midnight. Sarajevo’s packs of stray dogs, normally friendly and docile, start getting edgy and unpredictable. Their shrill call-and-response echoes across the valley, slamming off the mountains. As I walk up Koševo, toward the darkened graveyards, toward Gavrilo, two of them trot behind me before sprinting ahead full tilt, like predators in the wild. One of them starts lunging recklessly at speeding cars, barking out of its mind. I can barely look. I whisper a plea: Don’t make me watch you die tonight.

.

V. Tuzla, June 30-July 1, 2014

On the last leg of our trip, heavy rain falls on the winding, forested road north from Sarajevo to Tuzla. By now the disastrous spring rains should have run their course. The damage has already been done. In the Tuzla Canton alone, landslides and the brown, swollen Bosna River have destroyed hundreds of homes. Thousands of Bosnians are refugees once more. Goran squints through the windshield as excess water ripples and pools across the road. “Nature out of balance,” he says, a reminder that in Bosnia, things can always get worse. A roadside billboard with a skull and crossbones shouts “DANGER!” to warn of wartime landmines displaced and resurrected by the recent floods. A subsequent sign, apparently without irony, pitches a café called Vertigo. The Robert Plant and Jimmy Page album No Quarter powers through the car stereo: I couldn’t get no silver, I couldn’t get no gold. You know we’re too damn poor to keep you from the gallows pole. We pass up Vertigo and stop for lunch at the hillside restaurant Panorama, where clouds fog the view of the valley below. As soon as we sit, Goran asks the waiter for a good, stiff shot of rakija. “Better make it a double,” he says. “I’m driving.” We unleash a torrent of laughter.

As we approach Tuzla, a city of mining and industry, we survey the destruction. Debris from the floods lines roadside fences and clutters yards. A turbulent sky shifts and reconfigures its shades and layers of grey, permitting only slivers of sun and a thin, diluted streak of blue. A power plant’s enormous cooling towers, chain-smoking, superimpose their own brownish haze. Suddenly, traffic crawls. The floods have devoured a large section of our lane, forcing a long line of cars to snake off onto gravel and dirt.

When we get back on the road and come to the heart of the city, we see wreckage that’s man-made: the smashed windows and sooted, graffiti-tagged façade of the Sodaso chemical plant. It’s a gutted casualty not of wartime shelling but of an economically devastating postwar privatization; the plant was ground zero for the fiery citizen uprisings of last February’s “Bosnian Spring.” We enter a traffic roundabout, where a large banner encourages union solidarity – Sindikat Solidarnosti – and a young woman hustles by on foot, hunched, with no umbrella. Her shirt says “Sunny Beach Club” in English.

Near the town square, the site of the 1995 massacre that Tuzla is famous for, we park on the street in front of a Catholic school. Near the main entrance is an arresting scrap metal sculpture, eight to ten feet tall, of St. Francis. Gaunt, hollow-cheeked, with his eyes to the ground and his palms to the sky, he is the incarnation of hunger and despair. The artist has riveted, dented, crimped, and shredded the metal with reckless precision. Francis looks as though he’s been hit by shrapnel, or a shock wave, and he is literally unraveling, his thrice-knotted cords tearing away from his cloak of poverty. Wild birds – are they predators or prey? – besiege him, their wings stretched vertical and taut. No sentimental kinship binds these creatures to Francis; their only communion, their only solidarity, is in their intimacy with the abyss.

We’ve come for a lecture at the local atelier across the street from this St. Francis of Tuzla. The event has been arranged by Nigel Osborne, a professor, composer, and activist visiting from the UK and working closely with a young local university professor and activist, Damir Arsenijević. When we meet, Nigel strikes a note of hope. In his sixties, he is tall, bearded, and broad-chested, with a booming voice and infectious energy. He tells us that this is a chance for exploited, suffering Bosnians to reimagine everything, to remember that they “can change things fundamentally.”

Osborne’s connections to Bosnia run deep, back to the war, when he collaborated with activists and artists, like Goran and Susan Sontag, to keep Bosnians and Bosnian culture alive. Now, working with local university professors and activists in Tuzla, he’s invited tonight’s speaker, the economist Fred Harrison, a London-based contemporary of Osborne and an architect of Yeltsin-era land reform in Russia. Osborne and Harrison are touting such reform as a revolutionary alternative to rapacious, neoliberal global capitalism, reform that once had put Russia on the path to real social and economic justice before oligarchs hijacked and derailed it.

In his lecture Harrison calls the current global economic system “a cruel one,” a form of “cannibalism” and “medieval bloodletting” that sacrifices workers and youth in order to save the financial sector. Merging fluidly with the corruption of local elites, that system has left ordinary Bosnians desperate and unemployed at rates surging toward fifty percent. A revolution is possible, Harrison contends, but we will have to “build our minds anew” by returning to moral, non-ideological “first principles” of authentic democracy and collective ownership of the land. Tuzla’s unions and plenums – the emerging, town-hall style citizen assemblies – will have to lead the way, he says, in dismantling an entrenched system of greed.

Afterward at a restaurant on the square, Osborne is buzzing. I ask him what he thinks about Professor Harrison’s suggestion that Bosnia should seek the political and financial support of Great Britain. He thinks it could work. During the war, he tells me, Great Britain, unlike so many other western powers, started to repent for its tragic misunderstanding of the Bosnian situation. Now with the likes of William Haig and Angelina Jolie paying such close attention to Bosnia, there could be enough international momentum for real change.

Soon Professor Harrison walks in with the director Carlo Gabriel Nero, who filmed the evening’s lecture for Al Jazeera. We all have a date at a nearby café and bar, Urban, to sing sevdah, the Bosnian blues, with local professionals. The music – full of tremulous vibrato, of vocal oscillations encouraged by an accordion and anchored by an acoustic guitar – is not for the faint of heart. Osborne is fluent. He grabs his guitar and sits in. When he sings, all the Bosnians in the bar join him. They know these songs of love and sorrow by heart. After a while, I move back from the inner circle of musicians to the edge of the bar, where two Bosnians give me their sense of what it’s all about. One says that this is a kind of sijelo, a gathering with comfort food and live music, usually sevdah, where everyone feels like old friends. Another says that it’s about the pursuit and experience of merak, translated loosely as a moment of true happiness, ease, and no worries at all.

I thank them. It’s almost midnight. We’ve been at it for hours, and the crowd is starting to thin and fade. Everyone has somewhere to be tomorrow, when morning will bring the hope and the anguish of starting from scratch.

—Thomas Simpson

Born and raised in western New York, Tom Simpson teaches religion, ethics, and philosophy at Phillips Exeter Academy. He holds a Ph.D. in religious studies from the University of Virginia. From 2002-2004, he directed Emory University’s “Journeys of Reconciliation,” an international travel program exploring the intersections of religion, violence, and peacebuilding. That work brought him to Bosnia-Herzegovina for the first time. Subsequent visits have led to collaborations with Goran Simić on a collection of Simpson’s essays about postwar Bosnia, which they plan to publish in 2017. This fall, the University of North Carolina Press will publish his first academic book, American Universities and the Birth of Modern Mormonism, 1867-1940. He lives in Exeter, New Hampshire, with his wife, Alexis, and their two children, Blake and Will.

x

x

Photo credit: Leigh Backhouse

Photo credit: Leigh Backhouse

Cynthia Flood

Cynthia Flood

Dave Smith via The Poetry Foundation

Dave Smith via The Poetry Foundation

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

The

The  From the front pages of the novel

From the front pages of the novel