All photographs taken by the author.

All photographs taken by the author.

.

A note (unedited, in English).

Buenos Aires. 20.12.2016. A return — this seems to be one of the things I’m expected to write about. And now that I return, now that I find myself here, I haven’t even left the airport and I’m already toying with the idea of writing a return, perhaps just to surrender, to stop running away from that mandate. To write about a return to a hot place, by a fictional character, broken by (self)exile and memories. But how could this return be any different? What could this writerly return add to this well-trodden path? People — broken by (self)exile and memories — have been returning to hot places, for an audience, since Ulysses (the first one). And it’s a terrible destiny, to find oneself in the mouth of a lyrical poet. This is very likely the most dangerous part of returning, that poetic possibility, the dangerous and fake nostalgia all poetry entails.

.

I

Missing Buenos Aires is a daily routine. Some days the longing arrives after a sound — memories are triggered, homesickness kicks in. Other times it happens after a smell, any smell, heavenly or foul. Most times the longing comes after the wanton recollection of this or that corner, any part of Buenos Aires that in my mind looks like Buenos Aires should look. Some days the feeling is overwhelming and I can spend hours wallowing in self pity. Most times the situation is manageable. I am writing this, listening to Astor Piazzolla, because today is one of those days where I can’t handle homesickness very well. And the music helps with the fantasy, it feeds it.

Because the thing is: I never lived in Buenos Aires. I frequented Buenos Aires a lot. But I never lived there, never managed to settle there, had my name on a bill there, or a fixed abode, or a favourite café, or a library card. Unlike Dublin, Paris, and later London, Buenos Aires was too much for me — I couldn’t tame it, own it, call it my own. I used to spend many a weekend in Buenos Aires but I would spent this time coach surfing, mostly off my head after rock concerts, preparing a landing that never materialised. So I miss the possibility of Buenos Aires. And by missing its possibility I can miss my own hometown without the uncomfortable bits, without all the impossibilities, the proximities, the complexities and familiarities. The parts that can hurt.

I miss an imaginary Buenos Aires instead of a real Rosario. Homesickness is safer this way. And besides, like this I can plug into some universal motifs of Argentineanness — perpetuated by literature, tango, film (Argentine and international) — that I no longer wish to contest, since I have long given up trying to express the nuances and the complications of being an Argentinean. Of course I miss Buenos Aires. Of course I play football. Of course I am a gifted tango dancer. Of course I am a charming Lothario. Of course I am prone to fits of passion and — unlike British guys — fits of tears. Of course I can ride a horse. Of course I am a streetwise intellectual who likes to sit in cafés to solve the problems of the world.

I have, during these past fifteen years away from the possibility of Buenos Aires, become a simplified version of myself. My life is better without corners. And more importantly, in (self)exile I have become what I always wanted to be: the stereotypical porteño.

I miss Buenos Aires. How could I not write about this now that I am here, now that I return to the city I never left, the city where I never lived?

.

II

Ariel Ruzzo, professor of Latin American Literature in some college, University of London, arrives in Buenos Aires after a hiatus of five years. Actually make it professor of Comparative Literature, it will be easier to market. And Comparative Literature sounds less of a con. It sounds like he went abroad to do the vini, vidi, vici. Professor of Latin American Literature, for an Argentine character like Ariel, sounds like he escaped an economic crisis to then accidentally find his way into a modern languages department, where he ended up teaching unsuspecting and overpaying students the soporific drivel known as magical realism.

So Ariel Ruzzo — professor of Comparative Literature — lands in Buenos Aires after a hiatus of five years. He has come to sell a flat, a flat he inherited a while ago from an auntie, a flat in which he barely lived back in the late 1990s. He has found an overseas buyer, so it is only a matter of signing a couple of papers at the notary’s, some other papers at the solicitors’, receiving the money in his British account, and then back to London, to his musty office overlooking a central square. But there is also the thing with the boxes: he has to remove some boxes from his flat. Rita, an ex girlfriend, has been living there all this time, paying a symbolic rent. He would much rather avoid this, for a series of reasons, but he has already arranged to meet her tonight, have dinner together, old friends and all that, get the boxes out of the small storage corner under the stairs tomorrow. There must be five or six of them, said Rita. It can’t take him that long — most will go in the bin anyway.

.

III

I don’t remember where I was or why I was searching for images of Buenos Aires — it might have been a moment of procrastination; it could have been research towards an essay; it could have been anything. The reason for my search is no more but I remember very well the words, scribbled on a wall in some porteño suburb, in blue: “morirse no es nada, peor es vivir en Argentina,” — “dying is meaningless, worse is living in Argentina”.

These words pin down very well the atmosphere of the 1990s and early 2000s — my 1990s and 2000s. The decade felt like a slow death, punctuated by a long series of socio-political and economic upheavals. Like many others, this slow death — peaking with the crash of 2001 — sent me away. In my particular case, away from the possibility of Buenos Aires, on a journey to become Argentinean. No I don’t know what I was before; I only know that I became Argentinean abroad, probably while I was cleaning a toilet in Dublin, and the toilet was full to the rim with shit. This was a defining moments in my life. The realisation must have hit me then and there, or during the series of crap jobs I had for years on end. Somehow, suddenly, it was clear: who I was, where I was from, what I could aspire to. It was both humbling and enlightening.

I know Ariel Ruzzo left for the same reasons, even if he likes to play the scholarly card. But I still wonder if he became Argentinean abroad. Is it a generalised disease, this displaced becoming? What was his “cleaning an overflowing toilet” moment, if he ever had one?

.

IV

Ariel has had a stellar career. From his undergraduate studies in Puán’s School of Filosofía y Letras, to an MA in Cambridge, to a PhD in Princeton. A stellar career, from the very start, in all the right places. His thesis, which surveys the detective story from its birth in the mid 19th century all the way to the cinema noir, has become one of those rare documents that manage to leap outside of the reduced spaces of academia, in order to become a non-fiction classic. Reading the Detectives is into its sixth edition and in the process of being translated into French and Japanese. And Ariel is only forty.

And yet, success aside, here is Ariel, back in Buenos Aires, like any mortal, after a hiatus of five years, and even from before getting off the plane it is clear that it will be a difficult trip, that coming back to Argentina always involves a process of readaptation and submission. There is a transport strike and among the people exercising their right to piss off everyone else we should count those in charge of driving Ariel and his fellow passengers from the plane to the airport. And no, the captain won’t let them walk the scant hundred metres to the terminal, because it contravenes a series of safety regulations, even if passengers from other planes seem to be able to do the walk. A two hour wait, then, until British Airways manages to find a scab to do the job, in several trips, old people and those with kids first, no mention of literature professors — tenure opens doors but not all doors.

Ariel is back in Buenos Aires, after a hiatus of five years. He will have to come back later to get his suitcase — the strike — or get a courier to pick it up on his behalf. But he is back. Really back.

V

I should be taking notes, there are so many things to remember, so many things that could go into that piece about a return, things that add realism, the details, the lived feeling. Now that I find myself in Buenos Aires I should be noting things down, focusing on the contradictory bits, because people love the contradictory bits, not only of returns.

In the subte, Línea B, between Gallardo and Medrano: a mother with a disabled kid. She is having a loud go at him when he tries to eat a cookie and the crumbs fall all over the place, as he contorts visibly in pain with some muscular malfunction. The mother, tired, aged too soon — she resents the child, not that I have to guess this, because she says “I can’t stand you anymore,” in Spanish obviously, and then realises she needs to get off, and makes her move, politely asking the other passengers in the carriage to make room for her and the wheelchair-bound kid, all charm. This must be the first time in my life I hear a porteño say sorry, please, thank you. I am impressed.

This differs radically from my first experience of Buenos Aires on my own, perhaps in the mid nineties. I was walking down the avenue connecting the Retiro bus terminal with the city centre — it was an ocean of people. I was a bleary eyed lad coming to the smoke from a place where we swallowed the Ss at the end of the words. I was bleary eyed and scared and walking maybe too slowly and maybe in the wrong side of the pavement. A redhead guy suddenly turned up before me, kindly shouted in my face that I kindly move aside and pushed me aside, kindly. I almost fell kindly on the floor but I didn’t.

I wonder if this kind redhead is now as polite as the mother on the subte.

.

VI

The car flies down the Riccieri. Thank god the driver is quiet and Ariel can dedicate his time to watching the ugly houses both sides of the highway, sprouting like verrucas. Many an Argentine house built since the big migrational waves of the early 20th century is an example of Feísmo, the modernism and beyond of the impoverished European, at home and abroad, he reminds himself, almost as if he were thinking in footnotes. Who lives here? What is it like to live by the side of this road that never sleeps, with planes over your head, in one of these eyesores?

He is about to find a provisional answer to this question when the love motels catch his attention. He might have gone to all of them, here at the outskirts of civilisation. What a perfect site for love motels. A perfect place to stop for a shag before you make it to Buenos Aires and get lovelessly screwed by the city. He once was in one of these love hotels — or he imagines he was in one, or I imagine he was in one, which for a fiction piece would be the same — called “París”. He might have gone there with Rita, before he got the flat, when the options where shagging against a tree or in a rented room, shifts of two hours, mirror on the ceiling, adult channel not included in the standard rate. They might have gone to a room called “La Torre”. There might have been a photo of the Eiffel Tower glued to the window, both blocking potential perverts peering in from the parking lot and providing the ambience. Or, like I said, he could have imagined all this, or I could have, thinking about his ghosts, planning his return in my head.

But it doesn’t matter who imagined or imagines this — soon Buenos Aires is there, to the right and to the left, tower blocks, barrios, more lack of planning, advertisement hoardings that look like soft porn, seen from the elevated Avenida de Mayo. And a song starts playing in his head, make it a tango, make it Piazzolla, make it legible for foreign audiences, the ones likely to read this piece about a return.

.

VII

And the poor, their dark faces underground — it is always a matter of skin, whatever Argentineans might tell you. The pregnant woman with several children, begging barefoot in Pueyrredón, when I get off to change to the line that will take me to Once station, where I have to catch a suburban train to Ituizangó. The kids’ dirty faces, their shredded clothes. They might be the same poor kids I see later on the train — poor but with air conditioning. Poor but spoiled after the tragedy of Once in 2012, when fifty one died crushed like sardines, when the 3772 from Moreno to Once, decided to enter the station at full speed. I can’t guarantee trains are able to stop now, but at least they have aircon.

These kids or other kids, around eleven or twelve years old, drinking warm white wine from a plastic bottle, happily and prematurely off the trolley. And the itinerant salesmen, offering everything from sweets and colouring books to a CD with the latest hits of x radio — they are playing the songs with a contemporary ghetto blaster, the salesman showing off a voice probably acquired during a journalism degree. And the Africans. Africans in Buenos Aires — they are back. Speaking a language I can’t pin down, sitting in groups of two or three, ignored by the other passengers, for better or worse, travelling to provincia with bags and suitcases. What are they doing here? Where are they going? There used to be many of them in Buenos Aires but then they vanished — blended into the white population over the years, according to some; decimated by the flu and the war with Paraguay, according to the ones who know better. And now they are back. Like ghosts. Is there any other way of being back than as a ghost?

Everywhere is full of ghosts and ghosts taking down notes.

VIII

Ariel uses his keys and comes in unannounced. The door is heavy. He remembers the door being heavy but it must have gotten heavier during these past five years.

Soon he is riding the lift all the way to the sixth floor. It is an old Otis with scissor gates. He thought they had been banned — children kept getting their hands and feet crushed by the gates. But here is this lift with scissor gates and it feels like being in a film, cinematically moving up with the numbers of the floors painted on the walls turning up one after the other and this irregular chiaroscuro of shadows and lights, scrolling in vertical pans.

And soon the sixth floor. Ariel leaves the lift, closes the scissor gates behind him, and the lift disappears towards the ground floor, called by another person and the door of his flat opens and Rita is there, unwilling to be taken by surprise. And she looks beautiful, the same, she hasn’t aged a single minute. Or maybe he never paid attention.

IX

The dead. If I were to write that piece about a return, of Ariel’s return, I should make a reference to the dead of Buenos Aires. The dead might explain the ghosts, or add some material basis for them, or just some colour.

The dead of Buenos Aires, underground. Not as in buried six foot under but given a platform in the actual metro stations, on station names and writing on walls — the battles, violent men, terrorist attacks, catastrophes, accidents, disappeared writers. Caseros — Ejercito Grande versus Juan Manuel de Rosas (another station and a tough we love to hate) 1852. Pasteur / AMIA — vaccination / suicide bombing. Carlos Gardel — plane crash, Medellín, 1935. Rodolfo Walsh — killed in Constitución, 1977, disappeared. But maybe I am exaggerating, forcing wanton connections. Or maybe not, because Cromañón.

By the tracks, in the depths, a small mural consecrated to the dead in the fire of Cromañón, where almost two hundred music fans burned to death during a rock concert, in 2004. The choice of words in the mural, on the black wall, links to other deaths: Cromañón Nunca Más. Nunca Más, Never More. The words chosen back in the mid 80s to attempt to quantify and qualify the crimes of the juntas between 1976 and 1983. Nunca Más was the title of the book by the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons (CONADEP), two words that would also become a call to stop death. In the mid 1980s the call was to stop state terrorism. In the early 2000s a call to stop another type of death: one born out of the state’s disappearance, all the corruption and oversights that would make it possible for almost two hundred — many of whom were children — to die in a blaze.

A piece about a return to Buenos Aires wouldn’t be a piece about a return to Buenos Aires without some paragraphs dedicated to the dead. This is, of course, another trope I am expected to write about, another form of surrender, part of the demand that Argentine writers fill the page looking back towards this or that violent past. Disappeared, victims of terrorism or petty crime, any of these will do to please the reader. Perhaps the dead might grant me the attention of a publisher too.

.

X

And of course they have fucked by now. Ariel is smoking a cigarette, lying in his estranged bed. Rita is smoking too. Of course they are smoking.

And of course a dialogue will here ensue, one of those dialogues full of love, longing, and bitterness. Like Graciela Dufau and Héctor Alterio talking while promenading by the rotten Riachuelo in a 1982 film about another return, Volver, unimaginatively named after the tango tune with the same name.

Alfredo (Alterio) comes back to Argentina, tortured by (self)exile. He comes back for work, although not only for work. He is a successful businessman in the USA, and he comes back to Buenos Aires, in 1982, when the dictatorship is crumbling, and the Malvinas idiocy is yet to happen. He returns, and he works and he beds Beatriz (Dufau), an old flame. And then — or even before they get laid, I can’t remember and I don’t wish to watch this film again — they are walking by the Riachuelo, in a clichéd postcard spot better avoided, yet abused by art, cinema tango and literature. There are still dock workers here and there, because they had not yet been decimated by Menemism. And Alfredo and Beatriz walk, loving one another and hating one another in dub, in sepia, with corny phrases, so much to say, in so little time. And of course Beatriz is a journalist, just like Rita, who starts speaking over the dialogue in Volver, perhaps reading my mind, or Ariel’s, or perhaps to stop me from reproducing the original exchange of platitudes.

“Why did you come?” asks Rita.

“To sell the flat, you know that,” says Ariel. “And to see Buenos Aires…”

“I mean why did you really come? You didn’t really need to…”

“I was curious…”

“Tourists,” says Rita bitterly. “In just a few days they want to see everything: visit all the museums, watch the tango, the football. Everything. As long as it is authentic.”

“And I really wanted to see you,” says Ariel. “I’ve missed you.”

“Have you realised how much we sound like characters in a bad Argentine film?” asks Rita.

“It’s the fate of all Argentine characters,” says Ariel and lights up another cigarette. Or I might say that. But he definitely lights up a cigarette because I quit smoking years ago.

.

XI

And the dead of the AMIA, murdered in the terror attack of 1994. How many of them? Was it eighty five of them? The names are painted on the walls at Pasteur / AMIA — white traces against a black wall, also underground. I don’t count them.

The ideologues behind the attack were never found. The investigation pointed towards a cocktail of islamist terrorism, state and police complicity, inefficiency, and old school Argentine antisemitism. There was an Iranian connection and a national prosecutor in charge of the investigation. He was found dead twenty and so years later, in January 2015, a day before declaring before the congress, in a move that according to some would have compromised the then president Cristina Kirchner (who had recently signed a controversial deal with Iran in order to advance the investigation, if you ask some, in order to shelve it, if you ask others). As his death was investigated things started to turn up about him, dirty laundry. Inappropriate exchanges of information with the American embassy, bank accounts abroad, links to foreign secret services. No one will ever know who suicided him. Like very likely no one will ever know who bombed the AMIA in 1994, or the Israeli embassy some blocks away, two years earlier. Justice is so slow in Argentina, that frequently it never arrives. And everyone is a bit dirty, make sure to make this clear.

I can’t remember if it was after the attack on the embassy or the AMIA when a old lady on the telly, reflecting upon the atrocity, outraged and emotional, ended her speech with “why do they have to put a bomb here? They haven’t only killed Jews today. They have also killed Argentine people, innocent people.”

XII

Ariel spends the night with Rita. The next morning he goes for a walk.

If the piece had taken place during the 80s Ariel sooner or later would have bumped into a disappeared-theme demo. If it had taken place in the 1990s, he would have bumped into one against the political corruption and the economic misery that characterised the decade. In 2001 he would have bumped into a horde of angry citizens demanding that all politicians go — que se vayan todos. In the past fifteen years he would have bumped into demos for or against the populist saints or sinners who saved or destroyed the country, that bunch of holy crooks, the Kirchners — Argentina is a country of radical binaries, don’t ask me to explain this in this limited space.

And now, after hanging around Florida and Lavalle, Ariel is walking down Carlos Pellegrini heading towards Corrientes, being the tourist he is, when he bumps into a demo, pure coincidence. The posters betray the same lack of imagination as in any demo anywhere. The semiotics of red and black, block capitals, synthetic slogans. A large flag with Che’s face confirms that the lack of imagination in this opportunity is left-leaning. And here a closer look at the posters and signs: they don’t make any sense. Ariel feels dizzy but nevertheless starts to walk with the demonstrators, gets in the midst of the noise, unable to understand the language they speak (metaphorically) and he crosses 9 de Julio avenue with them, and then stops and watches them disappear banging their drums and singing the chants against the traffic down Corrientes, with that obscene erected Obelisk behind him.

He watches them disappear. Unable to process what is going on, what do they want, what is it about now? He can’t understand because he has spent five years away, because he has slowly disengaged himself from his country, because he doesn’t belong here any more — Rita is right: he is a tourist. And yet he is already thinking of a possible conference paper, why not a journal article: “Peripatetic Literature: Argentine Politics and the Poetics of the Demo”. The title just turns up in his mind. He doesn’t even need to know what the demo was about in order to write this — the reason can be found out later, or just invented. He only needs to know that the demo happened. That it will happen again. That Argentines love a demo. And that demos are just another form of literature. And that all literature can and should be compared. vivisected, CVfied.

XIII

I spend two weeks in Buenos Aires and never make it home, to the place where I was born and where I spent twenty five years of my life. Let’s just say that a number of personal and work-related commitments impede it. I get to see my family, most of them. But I don’t see my friends, except for the ones who have turned the possibility of Buenos Aires into a reality. A natural order is repaired by my inability to bridge the 350 kilometres that separate me from Rosario. Some friends verbalise their disappointment and I stop responding to their messages. Others stop replying to my fake apologies. The important part is that a heavy ballast is dropped: we should have stopped talking years ago — we were victims of the Dictatorship of Nostalgia that comes with social media.

I spend two weeks in Buenos Aires, meeting this or that writer or publisher or filmmaker, sorting out papers, buying books and films and eating meat and drinking wine. Working but not only working and having a reason to be here, for once. And taking down notes — I take down lots of notes, on my notebook. Obviously I take notes with a fountain pen, on a Moleskine — this is part of my process of simplification, of embracing the stereotype.

I take notes in bars, on the bus, on the train and the subte. And people peer at my notes but the notes are in English. A girl on the train speaks to me in English after eyeing my writing, “where are you from?” she says. I reply to her in Spanish. She seems disappointed and asks why I write in English, then. I reply that I don’t know. She laughs. She is beautiful and young, and gets off at the next station, Villa Luro. This girl was some moments ago sitting zazen on the train floor. I had never seen anyone sitting zazen in Buenos Aires. It is never all about poverty or misery, is it? Not even when I think for an audience, for the page, speculatively, erasing the complexities and colours, in order to please, to be read, to be synthetic and available.

At some point I start missing London. I count the days. Thank god the days fly. I can live a different lie there, one that feels real.

.

XIV

After one more session of love with Rita, more tender than passionate, and very likely sterile, hopefully, Ariel sets to the task of getting the boxes out from the storage place.

What he finds will colour the nature of his return, whatever else happens before or after. Perhaps he finds notes. Or notebooks. Yes, notebooks of his years as a porteño intellectual, the years before the Big Leap into other continents and into a properly structured way of life, a career. Or maybe he finds nothing of any significance. The thought makes him anxious.

He does open the boxes. The first two house old books eaten away by damp and cockroaches (do they eat books?). He moves these aside, keeps opening. Old clothes, old readers from his undergraduate degree years. Everything ready for the skip, smelling of moist and time and somehow death.

But the smell of coffee soon starts to fill the flat, the melancholia is aborted, and Rita turns up with a cup, wearing a long white shirt, barefoot, all post-coital happiness. She moves next to Ariel, crouches next to him, passes him the cup, kisses him on the cheek.

“It’s all rotten,” he says, Ariel, opening another box.

“It’s very humid down there,” says Rita; she sits on the floor, careful that the t-shirt clothes what some minutes ago was exposed in the open, because this is how old friends sleep together.

Paper, this is all paper, and yes, he finally gets to the notebooks. He had the foresight of wrapping them in cling film. They seem unharmed. Two notebooks, pseudo-Moleskine, national production, they will fall apart as soon as the cling film is removed. He moves them to a side, doesn’t bother with them, not now.

“All this can go in the bin,” he says, pointing at the rest of the boxes, the six stinking boxes, with their mouths open towards the ceiling.

“Polo,” says Rita, referring to the building doorman, “he can sort this out when he clears the rest of the rubbish tomorrow night, after I leave.”

“Is Polito still alive?” asks Ariel, surprised.

“He looks like,” says Rita.

“He must be,” says Ariel. “I’d love to say hi to him,” he adds. He won’t.

XV

I am waiting in the departures lounge, Ezeiza airport. I lie to myself, that I will be back before the end of the year, that this time I will make the effort to go back home, not to an ideal or imaginary place, but to the only place I really left behind, to whoever still speaks to me there, to my mother’s house, my childhood things, the books I wish I hadn’t read, the places where I used to spend my time.

They have wi-fi in the airport now — it works quite well. I play with my phone, read the news in English, respond to banal messages, and when I run out of battery look at the passing people, singling out my compatriots without effort, their familiar ways and blue jeans and gigantic Nike trainers sticking out in the flurry of wealthy Brazilian tourists, mugged Europeans on their way home, and air hostesses and pilots with their small suitcases rolling over linoleum floors.

I sit here, waiting to fly back to London, and I think about Ariel’s return, about how the rest of his journey might unfold for him.

In the next days, after relocating to an AirBnB flat in Palermo, he will dedicate full-time to sorting out the final details pertaining the sale. Rita will be too busy, organising her move first and settling into her new place later, to meet him until the very last moment. He will welcome this space, spend his time in the bookshops of calle Corrientes, the bars, perhaps even go watch a film in one of the old cinemas left in the centro, if any hasn’t been turned into an evangelic temple. He will end up signing the papers by the end of the week and receive the confirmation of the bank transfer the following morning. The notebooks will remain unopened until after the sale, the transfer, after all the to dos, and Rita. Until he has had time to breathe and properly realise that he has nothing left in Buenos Aires, that all his traces in this place are contained in these two notebooks. So he leaves it until this very last moments, when I am sitting at the departures lounge in Ezeiza airport, waiting for the plane that will take me to London, to the place we call home.

The cling film comes easily and the notebooks don’t fall apart. The first one — a clutter of blue and black ink — contains mostly quotes from this or that book. The second one, this is the one that matters. The first page makes it clear.

A note (unedited, in Spanish).

Ezeiza Airport, April 13, 2002. A departure. This seems to be one of the tropes I’m expected to write about. And now that I depart, now that I’m here waiting for the plane that will take me away, I toy with the idea of writing something about a departure, perhaps just to surrender, to stop running away from this mandate, or from the fact that I’m leaving. I’M LEAVING. And I don’t have a clue what will happen with my life, where I’ll end up, doing what. It’s such a cliché, for an Argentinean to depart, and to write about it. It’s a terrible destiny. But at least it’s something to do. And what’s more: departing is meaningless; worse is living in Argentina.

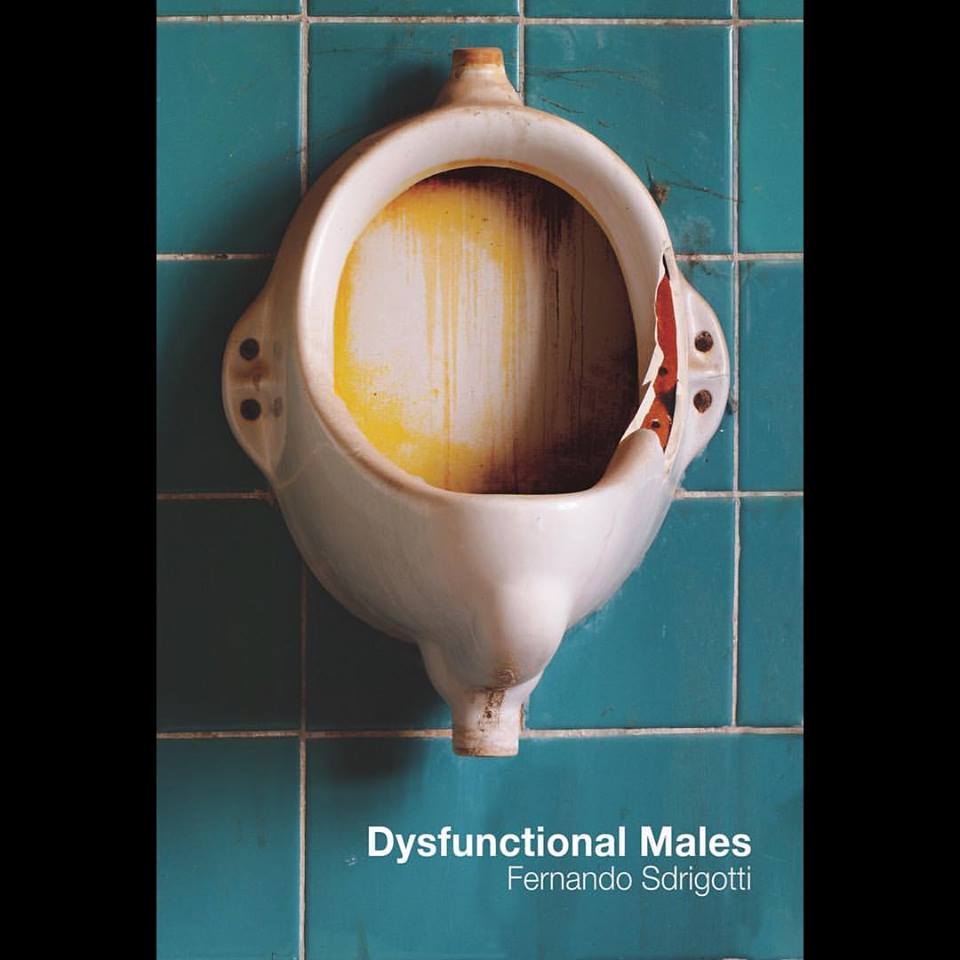

—Fernando Sdrigotti

.

Fernando Sdrigotti lives in London. @f_sd

.

.

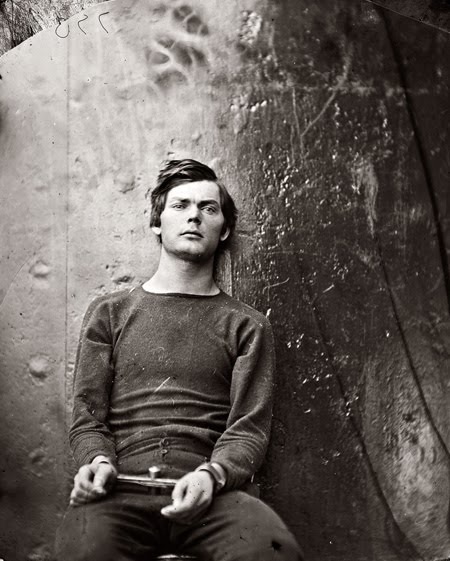

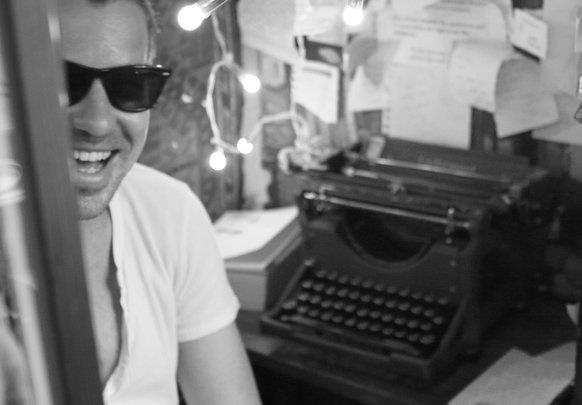

Still from the execution scene in The Passenger.

Still from the execution scene in The Passenger.

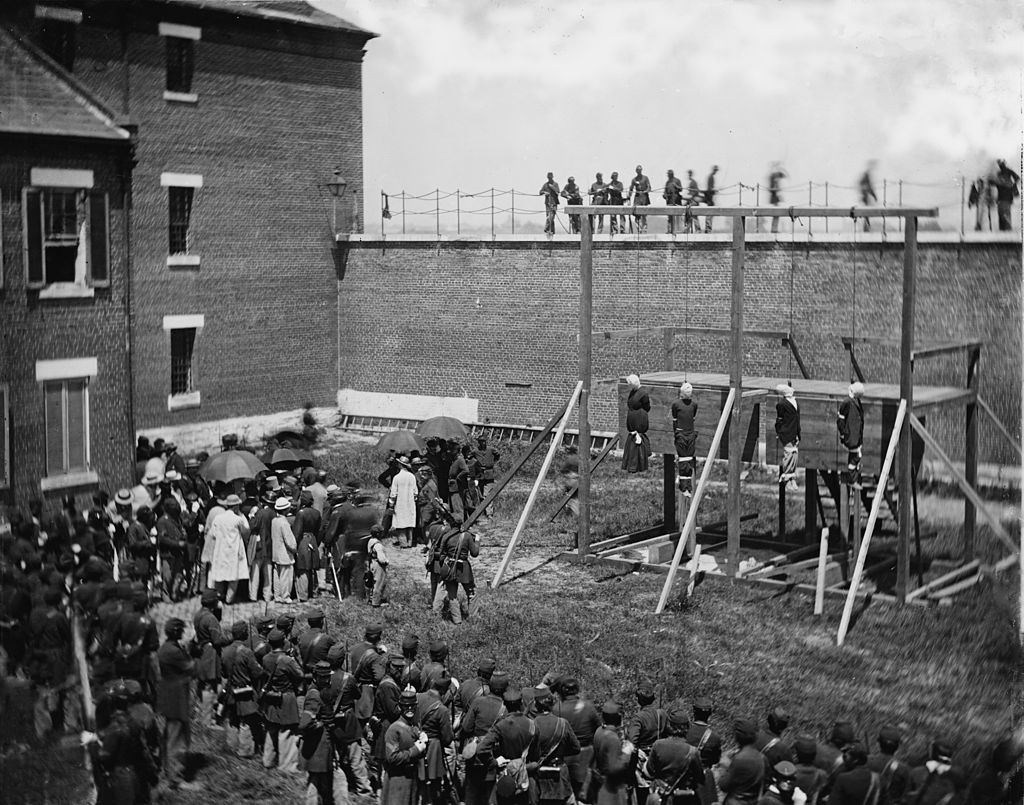

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865. Via Wikipedia.

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865. Via Wikipedia.

Stills from a video no longer available at islammemo.cc.

Stills from a video no longer available at islammemo.cc.

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Patrick O’Reilly was raised in Renews, Newfoundland and Labrador, the son of a mechanic and a shop’s clerk. He just graduated from St. Thomas University, Fredericton, New Brunswick, and will begin work on an MFA at the University of Saskatchewan this coming fall. Twice he has won the Robert Clayton Casto Prize for Poetry, the judges describing his poetry as “appealingly direct and unadorned.”

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.

Mark Sampson has published two novels – Off Book (Norwood Publishing, 2007) and Sad Peninsula (Dundurn Press, 2014) – and a short story collection, called The Secrets Men Keep (Now or Never Publishing, 2015). He also has a book of poetry, Weathervane, forthcoming from Palimpsest Press in 2016. His stories, poems, essays and book reviews have appeared widely in journals in Canada and the United States. Mark holds a journalism degree from the University of King’s College in Halifax and a master’s degree in English from the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. Originally from Prince Edward Island, he now lives and writes in Toronto.