Self Portrait as a Dead Man, 2011, oil on board, 16 x 13.5 in., collection of the artist.

Self Portrait as a Dead Man, 2011, oil on board, 16 x 13.5 in., collection of the artist.

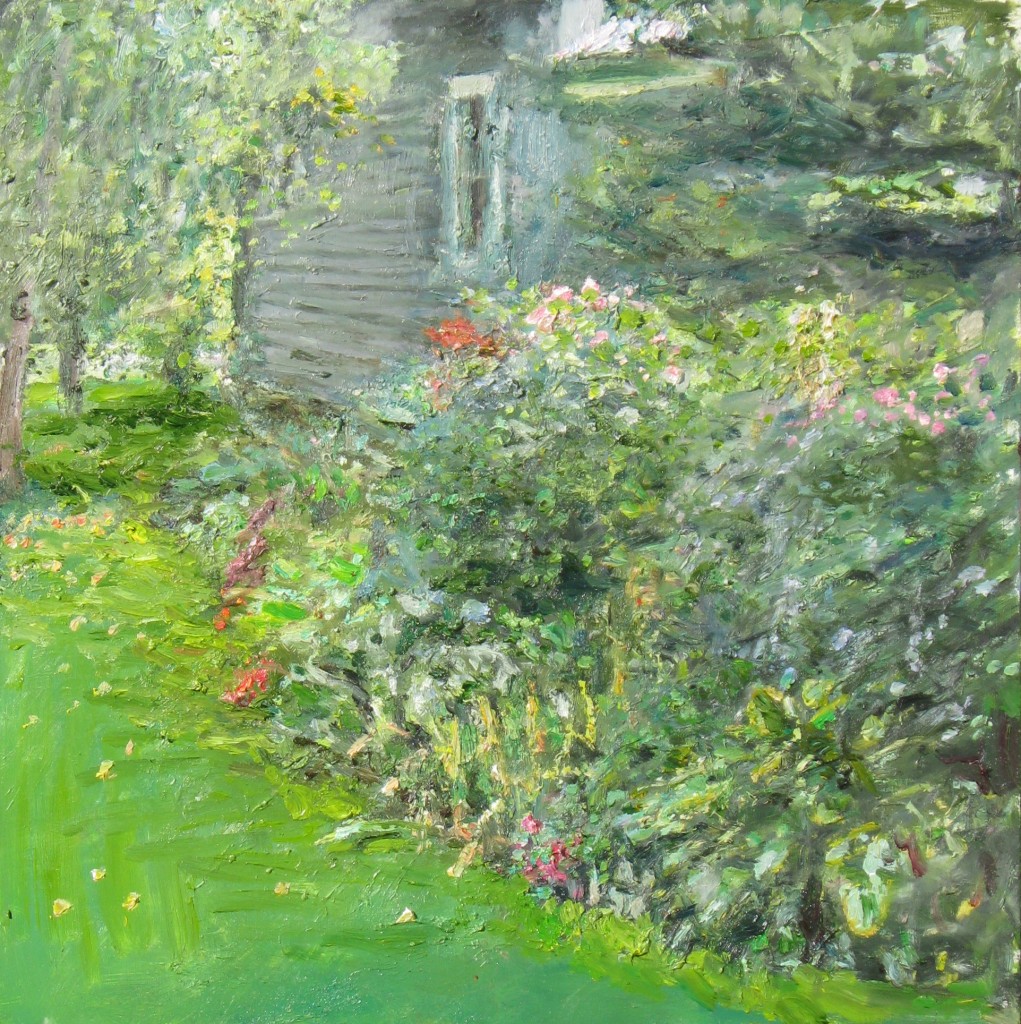

I am always alert to what artists have to say about their work. They are thoughtful, patient people who spend a lot of time by themselves working with their hands (something that always promotes a kind of detachment — you think with your hands and the rest is a kind of meditation). I first met Stephen May 25 years ago when I was writer-in-residence at the University of New Brunswick the first time. Stephen, despite the title of the painting above, is manifestly not dead (see the photo below), but still alive, painting and asseverating. When Stephen writes, he writes with passion and a style that rises here and there to the aphoristic; when he paints, his work shimmers with a kind of classic beauty. Herewith a sample of both, painting and text — the measure of the man and artist.

dg

—

This is about how inadequate logic, reason, passion, intelligence and imagination are in art. It’s about how reasonable it is to accept that. It’s about how misleading and misguided the word creativity is. This essay is not meant as a spiritual work, but it necessarily enters territory that sounds spiritual.

I want to make good paintings. Sometimes when I’m painting something good happens. I remember not the first time it happened, but the first time I realized what was happening. The words that came into my head were, “Oh, all I have to do is tell the truth!” or “Oh, all I have to do is put down what I see!” (It was a long time ago).

In the late 1800’s a critic named Albert Aurier reviewed an international exhibition of contemporary art in Brussels that included the work of Van Gogh. He singled out Van Gogh as a leader and praised his work in terms of its form, the way he used colour. Van Gogh wrote letters to friends in response. In one of them he wrote, “Aurier’s article would encourage me if I dared to let myself go, and venture even further, dropping reality and making a kind of music of tones with colour, like some Monticellis. But it is so dear to me, this truth, trying to make it true, after all I think, I think, that I would still rather be a shoemaker than a musician in colours.”

Van Gogh loved truth. He is not famous because he cut off his ear. He is famous because his paintings are good. His paintings are good because of his relationship with truth.

What is truth anyway?

I’ve painted good paintings and bad paintings, which is to say beautiful paintings and banal paintings. I’ve reflected on both experiences. I want to understand what it was that seemed right with me when the paintings were beautiful and what seemed wrong with me when they were banal. My experience has brought me to an understanding of the way my art relates to my life and how what is good in art, what is meant by good art, relates to what is good in life in general.

Beauty is just a word. There are many claims on it. Something is happening, though, in the art of Bach, Tolstoy, or Manet, for example, that is unpredictable and mysteriously complex. I use the word beauty to serve that phenomenon.

Artists sometimes say beauty is truth, and people sometimes say God is truth or truth is God. I tend to say those things now. When John Keats and Emily Dickinson equated beauty with truth, and when Gandhi and Simone Weil said truth is God, I don’t think they were using the words as a slogan for an intellectual position. I believe the words occurred to them the same way they occurred to me. And they occurred to me as a revelation but only after many experiences of the difference between true and false, beauty and banality. It is reasonable to be skeptical about the expression beauty is truth, but, ironically, skepticism led me to the expression.

Simone Weil describes prayer as paying attention. I thought I stopped praying when I was a teenager, but now I think perhaps I’ve continued to pray all along.

Painting is an act. Painting is living. The problems of painting — the problem of whether to paint or not, how to paint, what to paint — are the same problems we all face in just being human. They are the problems we have figuring out what to do with our lives, figuring out what’s possible. A person acts, and we find out what’s possible.

Shakespeare wrote plays.

Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player, that struts and frets his hour upon the stage and then is heard no more; it is a tale told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, signifying nothing.

So Shakespeare is possible. How did he do that? We want some explanation for his power and the continued effect it has on us. The only thing we can see and hear is the form, so we look for the secret there. Did Shakespeare have a secret formula? Did Bach and Beethoven? Did Manet and Monet? Did Gandhi and Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.?

What allows some people to leave us better off than we would have been without them? Those who do that sort of work are, invariably, un-secretive, and the infinite variety of the forms their actions (art) take suggests that there is something very un-formulaic at the root of their work. The root of whatever it takes to do something good outside the art world might be the same as within it.

Our ego lives behind our eyes and the world pumps it up to blind us. Our bitter disillusionment (those lines of Macbeth’s) steals upon us concealed behind the blind of illusions created for us, within our ego, behind our eyes.

A beautiful painting is never simple. It’s never just some canvas with colours on it, never just the image, what it may or may not symbolize, never just an artist’s diary or an artist’s taste and opinions, and never just a reflection of the artist’s culture either. We all tend to be distracted by the specifics of our lives, our passions, etc. Socrates is supposed to have said the only true wisdom is knowing you know nothing. And Einstein once said there are only two ways to look at the world. Either nothing is a miracle or everything is a miracle.

I need to use the word truth. Like the word God, it is a metaphor. I don’t think you can say God without imagining something like lord or father, something understandable. But if you use metaphor it moves mystery in the direction of non-mystery, and you undermine the significance, you undermine the psychic weight of mystery. You undermine the useful purpose of the word.

The thing about being human that makes me need to use the word truth is the hardest thing to put into words and the thing that if I could put it into words, might be the best use I could ever make of words. I am. I know I am because I experience. I know something else exists because I experience it. It’s a circular knowledge. There is no proving anything about myself, no proving anything about what I experience. One defines the other. There is no going outside that circle to see what’s outside it or to look back and see what that I really is, or what experience really is. It’s not even worth saying I know I experience as I can’t define either of the words I or experience other than in terms of the other. All our acts are acts of faith. Lived experience is normally so consistent it allows for a deep faith in nature and science, but as the Buddhists say, all is illusion.

I could ignore Socrates’ or Buddhist wisdom. I could ignore Keats’ revelation (my own) and call what happens within that circle knowledge. But it would be the first selfish act, the first subjective act that sanctions all subsequent selfish acts. It would be the end of wisdom. It would be the end of loving truth. It would be the end of true love. It would be the beginning of cowboys-and-indians. It would be the beginning of the presumption of knowledge and the sanctioning of all acts of relative good. It would be the end of goodness and love. It would be the end of beautiful action. It would be the end of beauty in my life. I wouldn’t paint anymore, or at least I hope I wouldn’t.

Truth is beauty is God. But I can only say that in the sense that I accept that all three words reflect an understanding that we really don’t know anything, that reason is limited. Beauty is mystical. It can’t be made un-mystical by social science or neuroscience (and yet it accepts those sciences). It accepts everything without judgment or fear or contempt. It isn’t fragile so requires no soldiers to protect it, nor rites to keep it holy.

We’re simply invited to fall on our knees. All our assorted lives and deaths lose all their gravity, they melt into air. We’re released from grasping, striving and collecting. Our fists are opened. We accept the ants on the kitchen counter, the dandelions in the lawn, our own nature, too. Poetry begins where separation between what’s solid and what’s mysterious melts away.

In Grace and Gravity, Simone Weil gives us an apt analogy. She describes a space normally filled up with our self, a space filled up with logic, reason, passion, intelligence and imagination. It’s only if we can remove our self from that space that there will be room for beauty or truth or God to arrive (she used the word grace). When we fill up the space again, there’s no longer any room for beauty. Reason and passion etc. are all manifestations of self love and they leave no room for beauty.

The mystical root of beauty and wisdom is in loving truth. Buddhist wisdom, Christian wisdom, and the wisdom of great art begin there. To love truth means knowing you know nothing. It means only accepting and accepting and accepting. It means being without agenda or prejudice. It means being without pride.

Egocentric taste is what is in the eye of the beholder. That’s not what I mean by beauty. I am not strictly speaking a religious man, but there’s no separation for me now between art and religion, painting and prayer, beauty and truth/God. If you consider aesthetics as philosophy of art, then for me aesthetics and ethics have merged.

I don’t know

A beautiful painting is not a representation of something you think is beautiful. If you see an image of an attractive and healthy young man or woman, or a sympathetic portrait of a beloved personality, a saint for instance, or an image of some idyllic setting, a place you’d like to be in, you have to be extremely wary. All of us involved in art have to make ourselves aware of the seductive power of imagery. What goes for art often fails to be more than expressions of taste or pandering to taste. Art very often fails to be more than seduction or manipulation.

You see, hear and taste, you feel beauty. How much do we miss though? Two people might be smiling at you, while one wishes you well and the other wishes you ill. Those smiles might look the same but they are different. It is a dangerous misconception that beauty is what something looks like. Beauty is what something is. Ugly, distorted, or plain things reveal themselves to be golden. Glittery things disappoint.

My struggle to come to terms with experience is the same as anyone else’s. We’re raised on illusions and comforted by them. My moments of disillusionment were unpleasant and life changing. We’re all taught by experience (or should be) the danger of mistaking illusion for truth. Some people wear blinkers their whole lives, loving escapism. Some people get cynical and don intellectual armour. Some love truth.

An old commandment, “Thou shalt make no graven image”, doesn’t make much sense to us at first glance. But if we make images of God from imagination, in words or pictures, and then love those images, it is really ourselves that we love. We create God in our image. We get what we want. We enter the brothel of illustration.

This isn’t new, nor will it ever grow old. It is in establishing whatever relationship is possible with truth that we begin to be beautiful, that our actions begin to be beautiful and the results of our actions, the traces we leave in our wake begin to be beautiful. Without that relationship all form is normal, banal. Within that relationship any form is beautiful.

In the pursuits of science, philosophy, theology, art, and in our everyday lives, truth is beautiful. Artists are prone to getting distracted from this no less than others. When I was young I liked art class best. When it came time to choose a career all I wanted was to play for a living, as opposed to work, so I chose art. It wasn’t too long though before I realized the only worthwhile thing an artist can do is love truth. I believe it’s the same for any career. I wonder what it does to a person’s soul if his career is ugly (spin doctors, etc.). In loving truth, the apparent incompatibility between our pursuits, between science and religion for instance, disappears.

I’m not suggesting we forsake intelligence, but beauty is not a strictly intellectual pursuit. You don’t need to be Plato to be beautiful. Being smart can just as easily get in the way. Maybe you need to be smart to realize that or to be able to put it into words (maybe it’s stupid to try to put it into words). A beautiful intellectual argument would be one free of rhetoric in the sense of persuasion. The rhetoric of persuasion is banal. That banality is an invitation for realities much worse than simply banal. We are attracted to intelligence for its own sake, to rhetoric and sophistry. But is leaves no room for love of truth. The rhetoric of persuasion is dangerous. It’s a truly ugly idea that if you’re better at persuasion than anyone else in the room, you win and truth is yours. Intelligence is for safe guarding ourselves against cleverness, distinguishing the difference between truth and rhetoric.

Elements of art

We can’t talk about art without talking about form. Art always takes a form, but the form that art takes isn’t what matters in art. The derogatory term academic art is reserved for art where form matters too much. It matters too much if you’re searching for new forms just as much as if you’re trying to conserve old forms. There is something more crucial than innovation. The painters Manet and Picasso are famous for breaking old forms and inventing new ones. That’s the orthodox story of western art. Really though they are famous because they are good, just like Van Gogh. Rembrandt was no breaker of form. All four of them are good in that they take form out of the precinct of words. Those who find refuge in form, the progressive and conservative alike never escape history, never escape their own time. Oscar Wilde asks us to be kind to fashion because it dies so young. I can’t muster much sympathy.

Manet’s contemporaries were offended by his lack of respect for what they considered to be the serious concerns of art. Things don’t change much. We get so caught up in our moment. Manet’s early paintings were designed as signposts, as if to say, “If you want to understand what I’m doing, just look at Velazquez (for example).” Manet’s painting, far from merely being a precursor to the triumphant art that followed, actually makes most subsequent painting look like window dressing and doodles, just as it made most of the painting of his contemporaries look like huge bags of brownish wind.

Sometimes when a person associates himself with the word realism it is meant to reveal their desire to dismantle false hierarchies. It is meant to express a willingness to accept all that is seen even though it may undermine the romantic/idealist notion that we are individually or collectively somehow the figurative center of the universe. It is meant as an acceptance of the fact that we are not the purpose or goal of existence. There have been many painters willing to put us in our place but none who have done it with such gentle humour, intelligence and kind sympathy as Manet.

Manet understood as well as anyone the potential of looking at something and painting a picture of it. He was reported to have said that a painter can say all he needs to say with fruit or flowers or even clouds. We can be moved generation after generation by paintings of nothing in particular, a glass of water, an empty field…by music without words. Manet’s perfect advice to artists: “If it’s there, it’s there. If not, start over.”

Chardin painted a picture of a brioche. He said you use colours but you paint with feeling. There’s a long list of great painters who looked at things and painted pictures of them, a long list of great paintings done that way. If sophistication prevents anyone from doing it today, there’s something wrong with sophistication. Van Gogh stuck candles to his hat so that he could see what he was doing when he painted outside at night. The French artist Marcel Duchamp called that stupid painting. The question of futility is empty. We are and so we do things. We can draw a moustache on the Mona Lisa or we can paint The Night Café, one or the other. The sublime and the ridiculous are Siamese twins. It’s a bit of good fortune if you don’t mind looking ridiculous.

We can’t talk about art without talking about media. There are practical advantages and disadvantages with respect to each medium, degrees of suppleness, degrees of ease of dissemination, etc. Ultimately though, we are the message. It is ourselves who are being delivered. We must tend to ourselves first. Our instinctual egoism is embodied in any new form and delivered by any new medium as naturally as in and by the old ones. That the delivery is increasingly more efficient is no great comfort.

A new medium is not necessarily a better medium. As a medium or technology becomes more complex, McLuhan’s observation that “the medium is the message” becomes truer. Love and empathy disappear within the complexity. We need to be careful that the increasingly complex media we adopt don’t cause this we that’s being delivered to become we-the-machine.

Painting most likely persists as a medium because of its infinite suppleness. It always bends to the force of the person who paints and makes it impossible for that person to hide. Anything that is good about them is plain to see. It’s almost as simple and obvious as singing or dancing. Less machine means less machine. It’s for those who love a person.

We can’t talk about art without talking about content (or substance). The word content is an acceptable word to stand for what matters in art. Whenever something gets formed (by humans or otherwise) all the causes, the obvious and the mysterious, of its being formed are contained within it. Content might be a word that denotes the limits of our understanding of what is there in the form, the limits of our ability to read it, to perceive it, as in, content is what I see, or content is what I know. Content might also be a word to denote all that is contained in form, independent of our ability to perceive it. When we form something we could define content as what we meant by forming it, or we could define content as what we are, as the force that determines the form. We don’t know what we are. We say intellectual content without knowing exactly what a thought is, what consciousness is.

If it’s true that the universe is in a grain of sand, that the content of a grain of sand is the universe, what then distinguishes a beautiful man-made form from a plain or ugly one, or nature from art? If content is what matters, what is the content in Bach’s form that distinguishes it from all other form in his time or before or since? What constitutes its value to us, if all sound, every sound, any sound holds truth in it? I would say that art is a human affair. A communion occurs. The origins of Bach’s music are mysterious. Bach willingly collects us within this mystery. It’s a kindness, a generosity on his part. When the sun shines, or the rain falls, or the volcano erupts, we can’t be sure it’s a kindness. A grain of sand isn’t kind.

We seek knowledge. We seem to be offered it but beauty takes it away again. We are stripped of the urge to be assertive. Maybe the beautiful thing about beauty is that no one knows how to do it, that no one ever has or ever will. We only know little pieces of a puzzle that keeps expanding in unimaginable dimensions beyond our potential and when we look again at that piece of the puzzle we thought we knew, that we so carefully and assuredly put in its place, it’s no longer what we knew it to be. I don’t know why Bach is so good. I don’t know how he so consistently avoids failing when it’s so easy to fail. I borrowed a Maria Callas CD from the library of her first recording when she was in her early twenties. The person who wrote the commentary for the CD ended with, “Listen to it on your knees.” It’s of crucial significance when one of us fails to fail.

There is a potential for art beyond metaphor. It would be better if people would understand that the value of art comes not from the nature of it being about something crucial and important, but from the nature of it actually being something crucial and important. Its value is not as illustration or documentation or story or metaphor, but as the embodiment of what is valuable. Imagery and symbols come naturally to painting which makes it particularly susceptible to this perceived limitation. 20th century painters abandoned the image to declare an understood kinship to music’s intrinsic abstract qualities. The same is true in modern dance and literature when they abandoned plot. There are no formal safeguards against failing to be beautiful, no formulas, but one understands the motivation.

I’m beginning to get angry at images. They seem to have an innate tyranny to mislead. When you see, when you feel with your eyes it happens in colour patches, in light and dark shapes. We respond to it in all the ways we respond to it ever since we’ve been human, by backing away, by approaching, in fear, in wonderment. But culture turns images into symbols that have meaning. The tyranny of the image is that it distractw one from realizing that the paintings aren’t symbols first, they are art first. They are embodiments of the painter, hopefully embodiments of feeling. For every painter who feels as Rembrandt feels, there are 100,000 painters whose symbols are the same as Rembrandt’s. For every painter who feels as Tom Thomson feels (in his plein-air sketches), there are 100000 painters whose symbols are the same as Thomson’s. This is the tyranny of the image.

Critical thinking

My best paintings were done by putting dark paint where it looked darkish, light paint where it looked lightish, like some glorified, faulty camera with two eyes instead of one and self-awareness instead of none. Cézanne said of Monet that he was “only an eye—yet what an eye!” I love Monet’s late paintings of the Japanese footbridge, when his eyes were ruined by cataracts and the operations to fix them.

I want so much to trust somebody. All I have is my eyes, ears and time to find out who I can trust, to discriminate between who might care and who might be looking out for themselves first. I think much of what is admired in the world is admired for being great examples of people overpowering other people. It’s taken it as a license to do the same. Hell is other people.

I’m searching for something and am compelled to walk away when it doesn’t appear to be present. If I can separate the good from the not so good, the difference between them becomes much clearer. The success of this phenomenon might be why there are long line-ups to get into the Musée D’Orsay every day.

There is an idea in vogue right now of artist as critical thinker. There is a relationship between art and philosophy, but they aren’t identical. Matisse said if you decide to be a painter you must cut out your tongue, you give up the right to express yourself by any means other than painting. He didn’t cut out his tongue though, and his art didn’t suffer. It’s good to hear it from the horse’s mouth. It would be even better if the horse could be as articulate as the horse experts. One tries.

Marcel Duchamp was a competent painter with interesting ideas. He stopped painting. He eventually ended his involvement with the art world altogether. He probably noticed the difference. Faithless action is impossible for a sincere person to sustain. Dadaism as it is manifested in his art—great art by function of its influence on later artists—reflects a strange cynicism with respect to the possibility of a person doing anything beautiful. Goodness saves each one of us at every turn. Disillusionment is with ideology. To abandon the cynicism that accompanies disillusionment means abandoning ideology. Icons are ideas. Marcel Duchamp has become an icon of iconoclasm. He’s his own mistake. When you destroy something, unless you arrange otherwise, the vacuum will be filled up again with normal things.

You can’t make anti-art. If you make it, it’s art. If you persist after realizing that, then you kind of need to accept that you’re the type of person who likes a joke at another’s expense. Duchamp kept attempting to present an art without value, anti-art, suggesting that the value we place on art is false. Every time he made something though, he realized he failed. The thing became art. By having been done, it inevitably participated in the phenomenon that is art and was valued as such. He realized that the only way this wouldn’t happen was if a thing remained un-done, un-made, that the idea remained unrealized. An unrealized idea, though, isn’t anti-art, but rather the absence of art.

The term conceptual art is a classic oxymoron. Conceptualism was still born. Art-as-idea has evolved from an absurdity to a concept of art reduced once again to illustration and documentation. Research, the collection of facts, has replaced perception, replaced feeling. Duchamp’s cynical act of pointing at a urinal and calling it art has spawned the current fashion of pointing. The art in this situation is not what is pointed at but rather the act of pointing and the implicit declaration. It is more vapid than the more traditional and self-centered pointing at yourself, drawing attention to yourself when you have nothing to offer, no beautiful intentions.

Duchamp was the first artist to gain a history book kind of success because he had nothing good to offer. The root of his powerful influence on today’s art world lies in the hope he gives to so many artists with ambitions for a similar kind of success, who, despite reasonable intelligence, like Duchamp have nothing good to offer. It is a telling fact to consider that some of the greatest paintings ever made were painted by Monet with his coke-bottle glasses in his garden in Giverny years after Duchamp pointed at a urinal. The history of what matters is more like a pulse than a march.

It’s in the nature of institutions to be conservative. Institutions must hold on to the ideas of themselves to exist. As we are in the era of art-as-idea, there is institutionalized sanctioning of cleverness within the contemporary art world that looks suspiciously like the 19th century Academy. It’s what happens when ideas replace feeling. There is a work of conceptual art that consist of a panel that has the words on it (in French) “Art is useless. Go home.” Without beauty, without feeling this is more or less true.

All artists, great and small, make things that aren’t beautiful. Sometimes some of them make things that are. A thing shouldn’t be held sacred just because Leonardo painted it or Mozart composed it. We’re allowed to walk away from art, even great art, if we find we can’t trust it.

Making beautiful things is beyond me. If it was just a matter of sincerity or intelligence or skill the world would be full of beautiful art. If it happens for me I’m never sure where it came from, or why it happened. It has many of the characteristics of accident. I realize I’m not controlling things. Simone Weil talks about waiting for God. All I can do is wait and hope for the beautiful thing to happen.

There was hope the industrial and technological revolutions would give us the opportunity to become our best selves but we sit in cars at drive-thrus and in chairs staring at screens and allow the means to become the end, the medium to become the message. We never seem to be up to our dreams, our utopias. We always imagine things that need us to be better than we are: Camelot, Star Trek, socialism, democracy. Occasionally a person saves us though, for a while, by disappearing, by being disinterested, by being selfless.

I have my moments

William Blake wrote, “If the doors of perception were cleansed, man would see everything as it is, infinite.”

As the best musicians listen, so the best painters look.

I’ve been trying to figure out the word tactile with an artist friend of mine. It’s one of those words, like beauty, used to denote something crucial in art but difficult to define. My daughter is a performance artist, a dancer. She uses the word presence in a way that I think might stand for a manifestation of the same crucial quality of art. When you stand in front of a painting, often you read the image as a few symbols and that’s all that’s there. You run into the end of the art quickly and moving up close to it or remaining with it for hours is fruitless. If a work is tactile, if a work has presence, you are rewarded by any kind of closeness.

When artists look, when that word means something, they can’t avoid seeing themselves there, present in their art action. Our undeniable and mysterious presence is inseparable from our experience (what we’re seeing when we’re painting) and our action (painting). It is one thing and it is the connection. As E.M. Forster said, “Only connect.” The eternal and universal miracle of realness is what connects us. When I paint a picture, if I’m looking, I am the man in the cave scratching on the wall. I see myself living and already being gone.

When I started out as a painter I emulated my heroes in a superficial way. Eventually I realized their paintings all had something in common that couldn’t be attributed to style or technique. The mechanics of painting never change much. We all use our hands and eyes and some painting supplies. Most artists are happy to share their methods. My method is pretty simple. I put green or red where I see green or red, dark or light where I see dark or light and make lots of corrections as I go. The results are predictably ordinary much of the time. The alchemy that occasionally happens has something to do with looking and feeling. Occasionally an image results that wasn’t imagined. A painting becomes that mysterious truth that is infinitely close and at an infinite distance.

Manet, Monet, Van Gogh, Matisse, Cézanne, Picasso, and Lucien Freud all lived in the era of the photograph. The unimagined image is, as are we, embedded in a miracle.

What it feels like when I’m painting is that I’ve gotten into a very small boat by myself and pushed off land out into a vast ocean where there are no fixed points to navigate by and everything’s constantly changing. I’m searching for an island in the middle of that ocean where there’s a spring with regenerative waters. It is only by being quiet that I can see and feel the subtle signs, the quality of the air and light, the push of the currents on the boat in order to sense where the island lies. The clumsiness of a large boat and the distraction of ideas would blind me. I wouldn’t be able to find the island.

I very often fail to find it anyways and return with nothing more than a documentation of facts I encountered on the way (stupid paintings). I can’t take anyone with me and I can only bring a small amount of water back. The only proof that island exists is the water I taste and bring back for others to taste. The water does what it does for those it works on. My responsibility is just to get into the boat and push off away from land and try to be quiet.

But for the water on that island I’d have no reason to get into the boat. I get to taste it too. All I know is how I am different as a result. Once you’ve made a good painting, a beautiful painting you’re driven to do it again. All arguments against beauty carry no weight against experience of it.

My most recent good painting happened this way. I was fearless, which isn’t normal. Usually I’m lucky if I become fearless along the way. Maybe I was fearless because I began by destroying a painting I’d been struggling with for years. I scraped and sanded something mediocre. I had no clue what the new painting would end up being. I didn’t think much about composition, the kinds of marks that I’d make, or the image that would result. I set the easel up facing a window I’ve painted countless times, something handy, and then the painting just sort of fell on to the canvas. I was in a wonderfully submissive state of acceptance of everything. I felt weightless. The ultimate form the painting would take wasn’t my concern. It felt like everything that I did, or might do, would be OK. There were no weighty decisions that were mine to make.

The Oxford dictionary defines grace as (in Christian belief) the unmerited favour of God; a divine saving and strengthening influence. It defines nirvana as perfect bliss and release from karma, attained by the extinction of individuality.

I don’t like to talk about technique. I feel like it would be misleading to talk about technique after realizing that I can make something beautiful with just a fat charcoal stick on a plain piece of paper. Though inferior tools and materials and clumsy and inefficient technique can frustrate an attempt, ultimately we can’t be saved by what colours we have on our palette or what brushes we use.

I have a number of techniques in my bag of tricks, all of them impatient. There are many painting techniques I don’t know, the patient and careful ones. Sometimes I find myself hopping from one technique to another in a short space of time during one painting session. I do that, not because I’m searching for the right one for that particular situation but because I’m trying to trigger the escape from technique. Things aren’t going well. I’m mired in knowledge and I want to get out.

In my bag of tricks there’s only one that matters. It’s not a secret and it’s supremely simple. Stop looking for your voice. Stop trying to distinguish yourself. Give up.

It’s simple

There is no substitute for feeling in art. Logic, reason, passion, intelligence, imagination, skill, maybe even what we call talent, are all realities of self. There is no beauty without their surrender. Feeling may not be all that’s required to be an artist, but it’s all that required to be beautiful. If you want art to be worth something, you need to know that it’s only beauty that saves the world, grace our reconciliation with gravity, love our relief from futility.

There’s a relationship between creation and destruction and a point at which the two seem to become one. Or perhaps neither exists except as different perspectives on change. In the fearless state of art, things are constantly being “created” and “destroyed,” constantly changing. Sometimes very good art will be perceived as irreverent and destructive, punk. It wasn’t their intention, but Manet and Van Gogh probably seemed like punks at the time. We trust them now. How do you distinguish between the good people and bad people when both ignore the laws? The question can make a conservative soul feel uncomfortable, mistrustful, angry and at sea. Beauty is found in realizing that we’ve never been anywhere other than at sea.

Great creators realize they are merely instruments. We place them on a pedestals and aspire to be there ourselves. Leonard Cohen once said something to the effect that he didn’t write his songs but he’s really glad we think he did. What’s rare is the understanding that none of us are creators. There are countless artists with Rembrandt’s or Manet’s skill but the skill is almost always wasted on inventions and opinion, on presumptions of knowledge. We’re all guilty of such waste. Rembrandt often was. Rubens was especially.

Their ability to find detachment for short periods of time doesn’t make saints of my painting heroes. Humans are clever, aggressive, territorial animals and are driven for the most part by biochemistry and overpowering social and survival instincts. Selfless detachment is difficult to maintain in the everyday world. I feel like I get to take little vacations from myself. Tolstoy said, “The one thing necessary, in life as in art, is to tell the truth.” In life, though we’re all aware of the risks of telling the truth.

The art history books are filled with art that flatters our species, magnificent follies, conceits of the intellect and imagination…pyramids and urinals, but there is no better reason for making art than being able to do for people what beauty does for people. On a number of occasions I’ve ended up weeping at the experience of beauty. I ask myself why I’m crying. It seems to be from some deep and unexpected sense of relief. I feel delivered from banality, from the sense that no-one cares, or from the sense that people’s concerns are exclusively worldly. It ends some kind of loneliness. It is redemption from narrowness and subjectivity.

Thomas Mann’s novel Death in Venice is a cautionary tale about confusing two types of beauty. At the end of the story he points us in the right direction. Attractiveness-type beauty leaves one with an ache to possess the object, the form. Truth-type beauty is only ever joyful. Whoever owns the object or form is irrelevant as beauty is not the form itself but what is manifested in it. In the experience of beauty, it is yours. It takes possession of you, it breaks your armour, and you expand into it. You participate in the artist’s expansiveness. It is unrestrictedly generous.

I want to do this, I want to make beautiful paintings, but I realize you can’t get there from here. You can’t try and make one. Striving to be great doesn’t help. You just need to do your job and hope for the best. Sometimes, strangely enough in telling yourself you’re going to make a bad work on purpose you can trick yourself into avoiding pretentiousness. The best thing an artist can be is nothing in particular; the best thing an artist can do is disappear. What’s left is infinite.

There’s a category in the thesaurus: artlessness. Under it you find ingenuousness, simpleness, naivety, innocence, unguardedness, unpretentiousness, sincerity, trustfullness, openness… reminds me of that lovely Shaker song.

In Shakespeare’s The Tempest Prospero the usurped Duke/magician has, in his daughter, one gift to bestow. This gift is “plain and holy innocence”. Prospero’s one great fear is that this gift won’t be received with respect. It is a gift that when respected “will outstrip all praise”, a gift that if held at an impossible distance by disrespect will issue nothing but “barren hate, sour-eyed disdain and discord”. Plain and holy innocence is the sine qua non of good art. With The Tempest Shakespeare passes the torch, and includes instructions.

Though we often reject critics and scholars as popes of culture, they often do what they do out of love and they’ve likely seen things we haven’t yet. But to love something does not necessarily mean you have insight into what makes it possible. Northrop Frye seemed to think that what enabled great art and made it special and valuable was what he called imagination. He also confessed to being unable to write a work of fiction.

I think most people assume that a work of art is a product of imagination, that Bach and Shakespeare had great imaginations. This idea implies that the work of art is generated within. Imagination is but a useful tool. But there’s a force to which it must surrender. It can provide situations but must surrender those situations to the infinite which the imagination can never be. Imagination gives us pictures of where we want to be, mythological gardens, things to strive for. We’re never up to our progressive ideas, our dreams. Everywhere we go, there we are. Without beauty life is nasty, brutish and probably too long.

I’ve condemned imagination’s role in the search for beauty. Perhaps others have a broader understanding of the word. Perhaps I should use the word fancy. Yet the root of imagination is the word image. It’s what our minds are limited to. Cézanne said, “I should like to astonish Paris with an apple.” As with Chardin’s and Manet’s, his paintings of apples continue to be astonishing. It doesn’t take much imagination to put an apple in front of you and paint a picture if it. Simone Weill wrote in Gravity and Grace, “The imagination is continually at work filling up all the fissures through which grace might pass.”

We need to acknowledge that our understanding is limited, yet our condition is a consciousness of limitlessness. In loving truth we have to accept paradox. If you acknowledge that agenda, prejudice, preconception and conceit are facts of life and therefore facts of art and then decide that your conceit is an art without agenda, prejudice, preconception and conceit, that’s quite the paradox…sophisticated innocence. No wonder it’s so normal to fail.

All you need is love

We’re proud of artists like Picasso. Some are even proud of people like Napoleon, all that strutting and fretting we do. The history of humans is the history of the failure of ideas. In studying history we hear the haunting refrain “never again,” “never again,” “never again.” The critical stance we adopt with respect to what we perceive as wrong is born of the conceit that we know better, the same conceit that gets us in to trouble in the first place.

The ambition to be beautiful is really an anti-ambition. It is the ambition to de-create the self, using Simone Weil’s expression.

In his play Antigone, Sophocles warns us to beware of hubris and to always hold the gods in awe. John Keats tells us in “Ode on a Grecian Urn” all we need to know on earth is that beauty is truth. The hardest thing an artist can do, the hardest thing a person can do, is act without self-interest. Once you have come to know that beauty is truth, you realize that any step away from beauty is the greatest danger we face. Perhaps this is what Dostoevsky meant when he said that beauty saves the world.

The last lines of George Eliot’s novel Middlemarch describe the selfless character Dorothea:

But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

The absence of beauty in a person is the root of callous indifference. The presence of beauty is the proof of love. The presence of it in what we’ve done is the great value of art.

Nobody can be good all the time, but if I can be good while I’m painting, at least that’s something, a few shining moments.

—Stephen May

——————————————-

Stephen May’s canvases have been collected by prestigious corporate and private collectors for over three decades and are included in the public collections of the Canada Council Art Bank, the Beaverbrook Art Gallery, the New Brunswick Museum, the New Brunswick Art Bank, the University of New Brunswick, l’Université de Moncton, the New Brunswick Department of Supply and Services and the Department of External Affairs. The Beaverbrook Art Gallery presented a solo exhibition of May’s work entitled Embodiments in 2006 and the following year he won the Miller Brittain Award for Excellence in Visual Art. May graduated from the fine arts program of Mount Allison University in 1983. He lives in Fredericton.

I empathize with artists like Stephen May that are seeking to express, regardless of their medium, what is essentially the profound mystery of life through their work. I first sensed this great mystery as a young boy lost in the rapture of a summer day long ago. I remember wondering what “this-ness” was, my immature understanding of being. That formative experience may have set me on the path to becoming an artist. At any rate, it opened my eyes to the world in a way that resonates to this day.

Yes, all is ultimately an illusion, as the Buddhists say, which is also why the Zen master sometimes feels compelled to give the novice a sharp whack on the head bringing him (or her) back to earth. There are worse things than becoming lost in the folds of Maya. Take self-righteousness, for example, a risk that all revelatory experiences carry, something that demands a rude awakening that in time may confer wisdom. The demand arises because we are often blind to our own behavior in this regard, projected onto the face of the other. Suffice it to say that true humility may be all the more difficult to attain when one’s intentions are truly noble.

When Mr. May writes: “that much of what is admired in the world is admired for being great examples of people overpowering other people,” sadly, I couldn’t agree more. Many of us long to be more trustful and less cynical. We struggle to rise above all the circumstances of our lives that breed suspicion and destroy trust. We understand that our fulfillment is predicated on the fulfillment of others: that we rise or fall together. To realize our fulfillment we must first listen to each other and be completely honest. This is not always easily accomplished. Part of the problem stems from our mistaking constructive criticism from others about our intentions, our work, our beliefs, or any number of things, as little more than an attempt to disempower us. I think that this is where trust between people is most sorely needed. Constructive criticism, appropriately applied and well taken can contribute a great deal to meaningful relationships. To this end I offer the following.

When Mr. May writes that the idea of the artist as critical thinker is in vogue today he is expressing an opinion that many others do not share, myself included. Critical thinking may have been in vogue during the heyday of Conceptual art, but it is scarcely the case today, where artists for the most part are not expected to critically assess issues raised by their work, or anything else for that matter. It seems that producing and marketing art is all that is required of most artists, at least, for most of those who wish to maintain a certain level of economic success. The mantra seems to be: “the less said, the better.” Unfortunately, critical thinking is not something that our society encourages. Even among artists and intellectuals critical thinking is not as widespread as one might suppose. Immediately after stating that the artist as critical thinker is fashionable he offers the following stale chestnut: “There is a relationship between art and philosophy, but they aren’t identical.” This pronouncement is both rhetorical and condescending and serves little purpose. Even during the period when Conceptual art was the only game in town (from the late 1960’s through the late 1970’s), few artists at the time (Joseph Kosuth, Victor Burgin, and some others notwithstanding) believed that art and philosophy was the same thing. If there is a relationship between art and philosophy perhaps it involves art serving philosophical ends, broadly construed. Meditations on beauty made present could be one such end.

Marcel Duchamp seems to be Stephen May’s bête noire. This is somewhat understandable given, among other things, Duchamp’s distaste for what he termed the “retinal” experience of art. Contrary to what Mr. May asserts, Duchamp never to my knowledge suggested: “the value we place on art is false.” Duchamp believed that the values we place on art are arbitrary (if not relative); his real target was “taste” as he understood it. Duchamp once remarked that the artist’s repeating him or herself is the ipso facto beginning of taste. Given this understanding, “failure” and “success” held little meaning for the old bricoleur. May cannot impute anything other than cynical motives for most of Duchamp’s work, principally his “un-done” or “un-made” art. I think that Mr. May is right to characterize Duchamp’s ready-mades as “the absence of art,” at least by the standards of art in 1915. But that was the point. For me, the ready-mades have an almost Zen-like quality (which may be why John Cage was one of the first artists to recognize their importance): commonplace objects are presented in all their modesty as subtle reminders of the illusions that we spin, about art, ourselves, life.

Paul Forte

Thanks, Paul, for the thoughtful comment. Much appreciated.

Thanks Paul. I feel I get awfully defensive a lot of the time. Doug cut out a lot of even more defensive stuff. Kind of ironic for someone who preaches dropping the armour. There have been so many artists who have been inspired by what Duchamp has done and who see the ready-mades the way you describe. I have an artist friend who has kept on telling me ( bonking me on the head ) to stop writing and paint. Reading what you’ve written makes me think she’s right.

Stephen

Still, anti-art is anti-art and I’m an artist so my being disturbed by how anti-art is accepted in the art world is reasonable. One would need pretty strange glasses to see Dada (disillusionment, nihilism) as Zen. Maybe Zen practice is helpful in avoiding suffering from Dada.

“You can’t make anti-art. If you make it, it’s art.” This is what you wrote in your essay, Stephen. Now you maintain that “anti-art is anti-art” (or not art), which reveals some confusion. I think it best not to bother with this silly term, “anti-art.” And why all the concern over what the art world accepts or doesn’t accept as art? Also, I did not write that I saw Dada as Zen. Again, for me, the ready-mades have an almost Zen-like quality. For many who admire Duchamp’s ready-mades, these enigmatic objects occasion much meditation, which may or may not lead to some conclusions about the nature of art. And for the record, I’ve never been that taken with Dada, primarily because of this movement’s political agenda, which was highly laudatory at the time (the period following World War One) given the carnage wrought by international capitalism, but nevertheless seemed to undermine the more positive, humanizing potential of art, at least for a while. And make no mistake, I include the pursuit of beauty as an important part of this potential.

Paul

I was a bit hasty in my previous reply and should have written that Dada’s political agenda was laudable or commendable at the time, not laudatory. Also, Dada began during the war and continued after the Armistice was concluded in 1918. It could be argued, however, that the general public, including many artists, didn’t became aware of the full horror of what had happened until after the war. The movement began as a protest against the war but in time developed as a critique of bourgeois values in general. I realize that my comment about international capitalism suggests an ideological perspective, but as I see it, this was the root cause of the conflict. Arms dealers backed by international bankers raked in millions at the cost of millions of corpses.

Paul

Stephen, This is lovely: “I want so much to trust somebody. All I have is my eyes, ears and time to find out who I can trust, to discriminate between who might care and who might be looking out for themselves first. I think much of what is admired in the world is admired for being great examples of people overpowering other people. It’s taken it as a license to do the same. Hell is other people.”

Incredibly insightful, telling and vulnerable. I learned from you – about me. Thank you (and NC) for putting it in print. Your friend is right. I look forward to reading more.

Julie J.

I think we’re probably a whole lot more together than we are appart. Semantics!! Words make talking so hard.

I see “anti-art” as art that is anti art (as in: art that doesn’t find any value in making art). I feel like we’re both in dis-agreement with that. That makes me happy. It’s so easy to become disillusioned, wars and greed in general take us there.

The more the “art-world” becomes a special place for people doing special things (like for arbitrary reasons, as if what we do has no consequences) the less it matters, the less it helps.

We can make the world a heaven or we can make it a hell depending on what we do right?

If you join in the disillusionment, join in the arbitrariness, join in the pointlessness, the selfisness that is sanctioned by relativity, it’s adding to the hell, even if it’s to protest or point it out. Dada can’t stop the next war.

In the middle of a world filled with disillusionment, a few things give us courage, confirm that something better is possible, give us faith to try. Dada doesn’t do that. It’s just an art-world thing.

I’m just frustrated by artists diving into the art-world for special art-world reasons when there’s so much potential for good action.

Stephen

I would like to return to something that you wrote in your November 23rd post. While disillusionment, arbitrariness, pointlessness and selfishness are often sanctioned or at least made acceptable by the doctrine of relativity in the art world and beyond, relativity itself is not the problem. Such negative traits could just as easily be ratified by absolutism (one need only reflect on history’s dictatorships, left and right, to realize this). If one holds some absolute notion of what constitutes art or beauty, for example, one might become no less disillusioned by everything that failed to conform to this notion, regarding it as arbitrary, pointless and selfish. But there may be a way beyond this apparent impasse. This requires approaching these perspectives dialectically. Actually, this is something that I try to do in both my art work and thought. What would a grand synthesis of the absolute and relative perspectives look like? It would, of course, depend upon the specific issue at hand, say, the problem of absolute versus relative beauty. A synthesis here would capture something of the essence of beauty (if there is such a thing), in both the natural world as well as the world of human culture, and show how this essence might be universally understood or appreciated. This essence could take many forms and be relative to the particular cultural constraints, and so forth, and yet have some archetypal basis.

Just a few thoughts.

Paul

We also might disagree about what constitutes “making art.” As you know, I put great store in the conceptual dimension of art making, which is an important aspect of our cognitive engagement in making and experiencing art. About disillusionment, wars and greed: I was psychically wounded as a young combat Marine in Vietnam, so I am particularly sensitive to the devastation that war brings and the utter folly of it. I have been strongly ant-war ever since my involvement with the ant-war protests in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s. This involvement was my redemption, this and the uplifting potential of art making. I agree with you, we can make the world a heaven or hell, depending on what we do. Vietnam almost destroyed me, but thankfully I did not fall prey to disillusionment or pointlessness. Actually, something miraculous happened. After the war, my art began to offer my life enormous meaning and a sense of wholeness that brings me joy every day. Given the nature of my work and the art world outsider that I am, I believe whole heartedly that it has the sort of potential that you find so important. Not just for myself but for others as well.

I think that if you wish to continue our discussion we do in through emails. This forum may not be appropriate.

Paul

Paul & Stephen, The forum is absolutely appropriate. Thank you for taking the comments section to a whole new level of involvement and discourse. Very much appreciated. It is rare to have artist actually talking to each other at this level.

Lynne Tillman was just on campus here at HPU giving a reading and a talk. During her craft talk, she discussed her memoir, which she called an anti-memoir. Afterwards, my CNF students said that what she described as anti-memoir was precisely what we were striving towards as a class, but what they were simply calling CNF. They wanted to know why she didn’t call it that too. It’s of course easy enough to explain to a class of students the fungibility of large scale genre-ological terminology. But, I their curiosity tied to another moment in Tillman’s talk in which she suggested the uselessness of all movement terms from a creative stand point because “all art that feels new, and by new I might mean something very old that feels new when you read it, feels new because it objects to what’s already been done.” I think its this process of objecting, which I think could also be described as problem solving for the perceived inadequacy of extant expression and prevalent models of expression, that gives the greatest chance of creating the thing May is calling “truth,” and that product of objection, might at any moment, resemble closest, almost any school’s conventions, or none, and might always be called, either by the artist or her dissenters, anti-art, out of a sense of rejection of identification with what others are calling art.

Which is a long way of saying thank you for the stimulating article and ensuing discourse.

Jacob, Wonderful comment. Thanks. I never tire of hearing what Lynne Tillman has to say. And I like the paradox of anti-memoir being identical with the cnf the students are trying to write — your solution to the paradox is very thoughtful. Truth having something to do with the act of objecting. Truth is forged in some dialogic act, a dramatic encounter. That’s a fascinating conjecture.

This discussion reminds me of Jeannette Winterson’s book Art Objects: Essays on Ecstasy and Effrontery(should be underlined or italicized but I can’t figure out how to do that). Worth checking out if you haven’t done so already . . . .

My daughter wanted me to read that. Maybe I should.

Stephen

There’s a part In Anna Karenina where Kitty innocently and simply points out the difficulties of and the solution to communication, the problem of how to overcome the problem with words. I love that book. So many bits like that.

My daughter (who is a contemporary dancer) suggested I read Art Objects. Being old and crotchety and sure of myself the title struck me as off-the-mark. So difficult to stop knowing so much, to keep listening and step away from your own words and the ideas they represent for you.

I think I understand a little better now how “art objects” might be true words.

I don’t really feel like I object though so much as ignore or struggle to avoid all the things that make the word “conventional” a bad word.

I’m running out of time on the library computer so have to post this before it’s….

Stephen

I’m sure there is a lot of art who’s spirit and intention is objection. I don’t feel like I’m objecting when I’m painting, almost the opposite of that. I’m trying to accept. I would want to say that art, beautiful art persuades, confirms, compels. It saves, it redeems. My instincts are to do the right thing (my success or failure not withstanding). I don’t know where it comes from.

When I stand in front of a thing like Rembrandt’s self portrait in the Frick, it makes me sure that it’s possible to do the right thing and it gives me the courage to try. Rembrandt was just a man like me.

Having become aware of Gandhi’s life and action, Nelson Mandella’s, Dr. King’s or Simone Weil’s I feel the same sense of being persuaded, compeled, redeemed. I call what they do beautiful too.

Shelley said that beauty is truth and that is all you know on earth. He didn’t say all you know in art.

Simone Weil said not to love Christ but to love truth and you will be led to Christ (the golden rule, blessed are the peacemakers, etc.) All cultures are led to loving truth and loving truth always leads to some version of the golden rule.

Art happens when we do things. Beautiful art happens when we do things too. What we do can make things better or can make things worse.

A just philosophy, any philosophy is humbled when you act. The best laid schemes o mice and men…

You might as well start out that way. On her way to participate in the creation or performance of a dance my daughter says “I must be prepared to be un-prepared”.

Why do I love truth? Because I can’t be beautiful, can’t act beautifully otherwise. You can’t trust me otherwise. We live with art. We must find those who we can trust with our lives.

I trust Beethoven. I trust Simone Weil.

Stephen

Totally accepting human beings are rare. Few of us are truly able to drop all the baggage that we carry from the cradle to the grave. And yet, trust is always possible when we come to understand our shared human burdens, something that requires openness. And while the love of “truth” is noble, even redemptive, the sobering question for all who espouse critical thinking is: “whose truth?” Most people can agree on empirical truths, however mundane, such as: “human beings exist.” But when it comes to beliefs and theories, truth will always be relative. Why? Because faith is the basis of truth in the first instance, and conjecture or speculative thought in the second. As we all know, matters of faith cannot be proven nor disproven, and theories are always (or should be) open to modification or even overturning. When we are really “prepared to be un-prepared” (I love this expression!), we are in the position to modify or change our beliefs and theories.

Paul

I was sitting having my tea a this morning and I realized that I’ve come to the end of my trying to put it into words.

I realized that it’s pointless saying truth is beauty. It’s one of those things you don’t know until you know it. I know I don’t know anything.

The law that grows out of the knowledge that truth is beauty is much more demanding of the person who knows it and who is determined to put whatever finite strengths they have into submitting to it than any religious or civil code of laws. Those religious and civil codes are likely the minimum that can be asked of people in order that things don’t get too ridiculous, in order for society to be bearable. When you’re acting beautifully you’re much harder on yourself than the religious and civil laws demand.

If you aren’t struck by truth being beauty it’s right not to jay walk. If you are struck by it, you have to contemplate the option of possibly jay walking in certain situations, but you’ll never know for sure. You can be led by the truth into acting contrary to the rules of art.

If you break the laws arbitrarily, if you break them for the sake of breaking them, for shock value, for the sake some dis-taste for conventional, that’s just self indulgence. That’s what the laws are always being designed to protect us from.

Totally accepting humans are rare. I’m struggling to accept, I’m struggling to abandon my beliefs and theories.

It’s been good Paul. Thank you. I re-watched Run Lola Run last night. “The ball is round. The game lasts 90 minutes.” Have a good game.

Stephen

Oops! Maybe this is like the karaoke phenomenon. Once they get up on stage you can’t get them off.

“I threw the urinoir into their faces and now they come back and admire it for its beauty.” Duchamp

What’s disturbing is how Duchamp is accepted, admired and emulated. Hannah Arendt and Simone Weil refer to the banality of evil. I don’t know where the term originated. I think Duchamp is accepted as a banality liscence.

The absolute truth about relativity. (joke)

For humans, truth will always be relative. Some people strike us as superhuman, as augmented humans. Some of those who seem to be superhuman though are really the opposite. They are disappeared humans, de-created humans. (don’t ask me how) Look at the eyes in a van Gogh self portrait or a late Rembrandt self portrait. Look at them looking. Look at what they see. They see the painter. They see the painting. They see the painter painting. That’s us. That’s all we know. No answer, just the infinite question.

Stephen

That statement by Duchamp about his “Fountain” (1917) is uncharacteristically combative. It is understandable that the work of Marcel Duchamp continues to disturb some artists, curators, critics, collectors, and others. Duchamp, perhaps along with Pablo Picasso, initiated a paradigm shift in the arts, which, of course, resonates to this day. Some people are more comfortable with fundamental change than others, it’s only human nature. Many of us tend to admire those with the courage and insight to change “the game,” people like Albert Einstein, Samuel Beckett, or Phillip Glass. These people are not superhuman, just very gifted souls. As gifted as such luminaries are, in the final analysis, their knowledge, while in their respective fields may be far more comprehensive than ours, is like ours also limited. Such people have each contributed something important to the great pool of human knowledge and understanding as well as expanding our imaginative and aesthetic horizons, all of which adds something to what humanity knows of itself, the world, and the cosmos. But in the larger scheme of things, we know very little. This is where I part company with the ambitious theoretical physicist who believes that ultimately everything is knowable. This is where my faith begins: we will probably never get to the bottom of this awesome and sublime mystery that we call existence.

I hope to enjoy a good many years on life’s stage, but I now must step away from this one. We are all indebted to Doug for providing this much needed forum. Thank you one and all.

Paul

Thanks Jacob.

Stephen