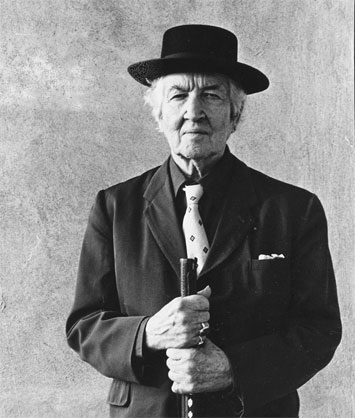

Robert Graves, Poet and Novelist…and Playwright…and Scholar

Robert Graves, Poet and Novelist…and Playwright…and Scholar

Some writers who gain fame as novelists continue to write poetry “on the side,” not unlike the little smear of cream cheese offered up with a bagel. Some writers quite sensibly refuse to be labeled; they write whatever they please, whenever they please….And some writers who are truly talented poets get shanghaied by the success of their fiction and never regain the courage or the emotional space to re-establish themselves as poets. The categories are many.

“I am a failed poet. Maybe every novelist wants to write poetry first, finds he can’t and then tries the short story which is the most demanding form after poetry. And failing at that, only then does he take up novel writing.” So said a fine novelist you might have heard of: William Faulkner. He knew a thing or two about writing, but his sense that every writer longs to be a poet can’t possibly be true, not if MFA programs around the country are any indication. The fiction track students hoot and holler at poets and mock them at every turn. The poetry track students do the same right back. At one reading, the poets might emote earnestly while the fiction writers snore; at another, the fiction writers read on and on and on while the poets pass around derisive notes in the form of double dactyls. Looking down on the proceedings, the gods would never guess there were prose writers lusting after poetry’s compression, nor poets longing to try out a novel’s expansive narrative thrust.

That said, there are a surprising number of novelists who started out as poets. Thomas Hardy wrote poetry throughout his life and considered himself a poet despite the fact that he published no poetry until he was 58 years old, having gained fame with his novels – Far from the Madding Crowd, The Mayor of Casterbridge, Tess of the D’Urbervilles, and Jude the Obscure – long before that. After the publication of his first collection of poems, he did not write another novel. James Joyce first published poetry; some might even make a case for sections of Ulysses and all of Finnegan’s Wake reading more like poetry than prose. D.H. Lawrence was a poet before he turned to fiction. Vladimir Nabokov published four books of poetry before ever attempting a novel. John Updike’s first book was a collection of poems, as was one of his last, published posthumously. In between, he published six other volumes of poetry, a fact which surprises quite a few of those MFA students mentioned earlier.

The list of poet-novelists is a long one and includes Rudyard Kipling, Robert Graves, Muriel Spark, Randall Jarrell, Czeslaw Milosz, Michael Ondaatje, Margaret Atwood, Anne Michaels, Fred Chapelle, Russell Banks….I’m sure you can think of more. Some writers who gain fame as novelists continue to write poetry “on the side,” not unlike the little smear of cream cheese offered up with a bagel. Some writers quite sensibly refuse to be labeled; they write whatever they please, whenever they please. Some continue to think of themselves as poets first, novelists second, no matter what the sales figures or their publishers tell them. Some are definitely better fiction writers than they are poets and admit it, but continue to write poems; some are in denial and their publishers don’t want to antagonize them by saying, “Enough” – those poems get published despite their poetic failures. And some writers who are truly talented poets get shanghaied by the success of their fiction and never regain the courage or the emotional space to re-establish themselves as poets. The categories are many.

Both Robert Graves and James Dickey fall into the troubling category of poets whose reputations rest on a single novel that the wider public embraced – Deliverance for Dickey, I, Claudius for Graves. These men considered themselves primarily poets, but today few people read their poetry. It’s not just time and changing taste that accounts for that. Maybe Hollywood contributed to the switch – it’s hard to fault Sir Derek Jacobi for delivering Graves’s Roman emperor to us in a way that burned him into our consciousness forever. Ditto the talent of director John Boorman when taking four men on a fictional hunting trip down a river in Dickey’s northern Georgia.

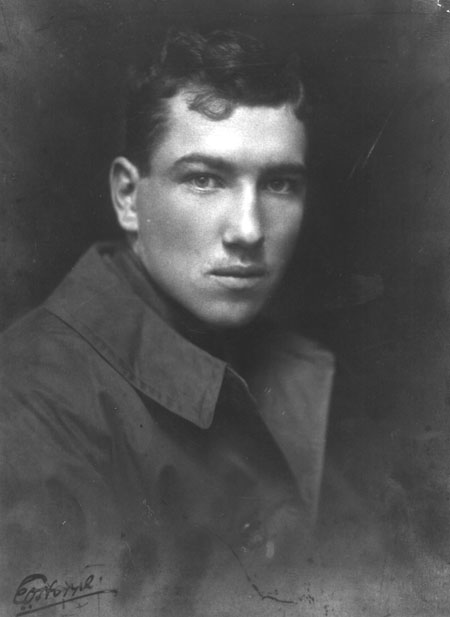

There’s no doubt at all that James Dickey deserves to be remembered as a poet. After a late start with his writing (he worked for an advertising agency until he was thirty-seven), he produced five books of poetry in just five years (1960 to 1965), won a Guggenheim Fellowship, won the National Book Award and was named Poetry Consultant to the Library of Congress (equivalent to today’s Poet Laureate.) But his reputation now seems to rest on dueling banjos, Georgian hillbillies, and a down-on-all-fours-pig-squealing rape scene in his novel-turned-film, Deliverance. The novel was a bestseller and the film brought national attention to Dickey (who made a cameo appearance in it as a Southern sheriff.) His adapted screenplay of the story even brought him a Golden Globe. But Dickey’s accomplishments as a poet suffered for it (he never again had a collection of poems that was a critical success, despite more than twenty volumes of poetry in the three post-Deliverance decades before his death.) The New Georgia Encyclopedia says “His misbehavior at public events, his disorderly personal life, and his self-destructive alcoholism only enhanced his public image as a masculine, burly poet and man of American letters,” but it’s more likely that Dickey’s wonderful work as a poet will get dusty on academic library shelves, and Burt Reynolds will take home the honors for masculinity.

…and on the set of Deliverance with Burt Reynolds

…and on the set of Deliverance with Burt Reynolds

Dickey’s style involves a precise ear for the rhythm of the words – his poems might not adhere to rules of form, and there is no formalized rhyme in the poem that follows, but Dickey definitely constructed it with a spoken cadence in mind. Reading it aloud, you hear the often eight- or nine-syllabled lines distinctly, you hear their three strong beats carried through to the final line. As the poet and Orange-Prize-winning novelist Helen Dunmore said, “Maybe it’s because the first things I wrote were poems – and very likely the last things will be poems too – that I’m convinced work has to grow into its own rhythm, inside the head.” Dickey, too, as a poet first and last, hears the rhythm of words. His sometimes violent imagery (in his poetry as well as in his novels) made many people squirm – it engaged “nature,” but not Mary Oliver-style, not as a source of inspiration and self-awareness; rather, Dickey’s nature (both poetic and – from what I can tell – personal) was primitive, full of blunt force, and sometimes theatrical. He once said, “I want a fever, in poetry: a fever, and tranquility.” The fever more often than not trumped the tranquility, but I think he managed to capture both in my favorite Dickey poem, “In the Tree House at Night.”

In The Tree House at Night

And now the green household is dark.

The half-moon completely is shining

On the earth-lighted tops of the trees.

To be dead, a house must be still.

The floor and the walls wave me slowly;

I am deep in them over my head.

The needles and pine cones about me

Are full of small birds at their roundest,

Their fist without mercy gripping

Hard down through the tree to the roots

To sing back at light when they feel it.

We lie here like angels in bodies,

My brothers and I, one dead,

The other asleep from much living,

In mid-air huddled beside me.

Dark climbed to us here as we climbed

Up the nails I have hammered all day

Through the sprained, comic rungs of the ladder

Of broom handles, crate slats, and laths

Foot by foot up the trunk to the branches

Where we came out at last over lakes

Of leaves, of fields disencumbered of earth

That move with the moves of the spirit.

Each nail that sustains us I set here;

Each nail in the house is now steadied

By my dead brother’s huge, freckled hand.

Through the years, he has pointed his hammer

Up into these limbs, and told us

That we must ascend, and all lie here.

Step after step he has brought me,

Embracing the trunk as his body,

Shaking its limbs with my heartbeat,

Till the pine cones danced without wind

And fell from the branches like apples.

In the arm-slender forks of our dwelling

I breathe my live brother’s light hair.

The blanket around us becomes

As solid as stone, and it sways.

With all my heart, I close

The blue, timeless eye of my mind.

Wind springs, as my dead brother smiles

And touches the tree at the root;

A shudder of joy runs up

The trunk; the needles tingle;

One bird uncontrollably cries.

The wind changes round, and I stir

Within another’s life. Whose life?

Who is dead? Whose presence is living?

When may I fall strangely to earth,

Who am nailed to this branch by a spirit?

Can two bodies make up a third?

To sing, must I feel the world’s light?

My green, graceful bones fill the air

With sleeping birds. Alone, alone

And with them I move gently.

I move at the heart of the world.

As for Robert Graves, how sad it will be if his poetry fades into the background and the light only shines on his fiction. Yes, he wrote plays, he wrote literary criticism, he was a consummate scholar, he wrote I, Claudius, but he was also a poet’s poet, with a command of so many formal poetic devices that reading his poems is akin to alchemy – base metal into gold.

The best example of his thoughts on the nature of poetry is found in his poem, “Flying Crooked.” Substitute “poet” for “butterfly” and you’ve got a perfect description of what a poet does.

Flying Crooked

The butterfly, a cabbage-white,

(His honest idiocy of flight)

Will never now, it is too late,

Master the art of flying straight,

Yet has- who knows so well as I?-

A just sense of how not to fly:

He lurches here and here by guess

And God and hope and hopelessness.

Even the acrobatic swift

Has not his flying-crooked gift.

I hope you will go back, read the poetry of Dickey and Graves, read the poetry of Atwood, Carver, Hardy, Nabokov, Ondaatje or any of the others I mentioned. There is something addictive about flying crooked, that’s for sure. And the plain truth is that few writers with a knack for it ever stop.

—Julie Larios

Julie Larios has had poems chosen twice for inclusion in the Best American Poetry series. She is the winner of an Academy of American Poets Prize and a Pushcart Prize, and has published four collections of poetry for children.

.

.

Thank you, Ms. Larios, for this essay. I studied Dickey in my undergraduate days, “Buckdancer’s Choice” my favorite, but I have been too long away and I must find him again. I wonder though, about the fine poem you include, if perhaps pine cones really fall like apples (with a thud) or if perhaps they fall more like pine cones.

satchdobrey, you are right – it’s likely that pine cones fall like pine cones when they fall, though I’m not sure windfall apples fall with a thud, not in late autumn with leaves on the ground. I’m glad, though, that Dickey had poetic license to make those pine cones fall like anything he wanted. Dickey’s whole poem here takes that license and runs with it – whoever embraced that pine tree, for example, didn’t make its limbs shake via heartbeat, right? Glad you liked the essay – I enjoyed looking into the topic.

Yes, upon re-reading, I see there is another device at work – that of a heartbeat shaking the limbs. Without getting too wet, one’s imagination can make that leap, I suppose. Still, hard to imagine a treehouse in a Pine Tree. If you could find the right Pine for a treehouse, then surely the cones may fall “like” apples from such a tree. Can you guess, I have a lot full of Pine and Apple Trees. Nevertheless, I did enjoy your essay and remember watching the PBS showing of “I, Claudius” in the 70s. Derek Jacobi stars in 2 series currently playing on PBS Sunday evenings in my town. Well done,

Satch