My friend (and long time NC contributor) Michael Bryson’s wife, Kate, died of cancer in May, after a brief, sweet marriage. Words fail.

But words were their common ground and meeting place, their sign of courage. Both Kate and Michael knew you’re not a victim if you keep talking, writing, thinking, questioning and defying. All through her treatment, Kate blogged with immense intelligence, grace, wit and courage at her site Auntie Cake’s Shop. When she no longer had the strength, Michael took over for her. Along the way, Michael wrote a gorgeous essay called “My Wife’s Hair” and a “Dear Kate Letter” and fugitive, poignant observations such as “Breast Cancer Can Put You in a Wheelchair.” I place all these links here, along with Michael’s essay, as a memorial to their life together.

dg

§

In the weeks before and after breast cancer ended my wife’s life on May 23, 2012, I was unable to read.

Surprising? No. But for me, a life-long reader, an existential risk.

I read, therefore I am. Books, engagement with literature, the pleasure of the text, whatever you want to call it, the continuity of my life is sustained by reading.

I use the present tense (“is” instead of “has been”) because I believe in that continuity, even though I am suffering (another self-conscious word choice) a break, a gap, a malfunction.

I’ve stopped reading. I’ve stopped being myself.

I’m grieving. I’m in the process of becoming someone new.

First, there was only the stress of the disease. Then, there was only the stress of her absence.

But there is also continuity (I believe, though I also disbelieve it). I’m still here (somehow; it seems miraculous). And so are her two kids (eight and twelve). My role as patriarch sustains me most days. My identity as a reading person has paused, but my identity as (step-)daddy remains abundantly active.

I want my reading identity back. I need my reading identity back. (My reading identity will crack the code for the next phase of my mysterious future I believe, though again without knowing why; without being able to articulate the slightest reason.)

So, then, how? Or rather, what?

Waiting for Godot by Samuel Beckett. Mrs. Dalloway by Virginia Woolf.

I couldn’t have predicted this, but this pair is what I want, need, to read right now. This is the ONLY pair that I CAN read right now.

My attention span for reading is travelling along a narrow band. Or perhaps I should say that the signal has only recently returned and it remains faint. I can only hear certain frequencies.

Why is it that I can hear Beckett and Woolf?

What are they saying that resonates with my current dilemma?

*

“I can’t go on, I’ll go on” (Beckett, The Unnameables).

Kate is buried in the cemetery that is half-a-block from my house. When Naomi was three, she used to yell at the cemetery as we drove past: “Hello, dead people!”

I reminded her of that recently, and she didn’t remember.

So much is transitory.

I go to the cemetery regularly to say hello to Kate. A planter with flowers serves as the headstone at the moment, and I go water it.

Sometimes I cry. Sometimes I don’t. The earth over the grave is still sand. They haven’t re-sodded it. I’ve written “KO” in that place. Someone told me they were wandering in the graveyard and thought, “Ah, that must be Kate’s place.”

I walk away from the grave thinking, “I can’t go on, I’ll go on.”

Why should I go on without her? There are, of course, a multitude of reasons; the kids chief among them. But I find it most convincing to say simply, I will go on, because I will.

Derek Weiler, the editor of Quill & Quire when he passed away in 2009, had “I can’t go on, I’ll go on” as a tattoo. He had a life-long heart condition that slowed him down and eventually stopped him. That’s where I first heard the phrase, but now it’s part of my linguistic DNA.

Waiting for Godot riffs on a related theme. Not about “going on;” instead, “waiting.”

The play begins:

ESTRAGON: [giving up again] Nothing to be done.

VLADIMIR: [advancing with short, stiff strides, legs wide apart] I’m beginning to come to come round to that opinion.

Or as one meditation teacher of mine (and Kate’s) said, repeatedly: “Nowhere to go, nothing to do.”

We ended up in meditation as a result of a book called Full Catastrophe Living by John Kabat-Zinn. Kate’s GP recommended it, to help with the anxiety of the disease. And so we discovered the field of psychiatric oncology. The book is based on a meditation workshop. We asked if there were not such workshops in Toronto, and soon we were signed up for one.

We were not in a hurry to go anywhere, because we knew the only place the disease had to go was somewhere worse. We were content to wait. To remain in “the present” perpetually. Putting off thoughts about tomorrow as long as possible. (While also acknowledging what was happening.)

We found ourselves at the hospital often, waiting. On one occasion, Kate had an appointment with her oncologist for 3:30 in the afternoon; we finally saw the doctor at 9:30 that evening. When we left, the entire hospital wing was empty.

Kate said, simply, “Thank you for seeing me.” Pushing away anxieties and letting go of the things that we couldn’t control had become by then a central element of her life, her way of living, her way of being.

*

Liminality is another word from this period.

Merriam Webster gives the definition of “liminal” as:

1. of or relating to a sensory threshold

2. barely perceptible

3. of, relating to, or being an intermediate state, phase, or condition.

Kate wrote on her blog a number of times about being in this “in between” space, also contemplating the Buddhist term “bardo.”

After her death, I found the following in one of her notebooks:

Liminal space –

space between transition

between living and dying

– have a dual awareness

* awareness of both living and dying

bottom line:

waiting

noisy

but not real sound

a pot to boil

taxi to come

a friend to arrive

a plane to catch

liminal surprises

mail, books, letters

from afar

show tunes in a cab

time to sort your thoughts –

so long as there’s no missed deadline

liminal as missing something

amiss/a miss

rather than liminal as space

entity – distinct entity

or something lost

nowhere to go – nothing to do

nothing to do but breathe

air

gas bubble

coursing through

dark region

surfacing

breath, required

necessary, but not

aware of it – life

we cease when we

stop

but we don’t know when it is

happening

we are only aware of

our stopping when the catch in our

throats hitches onto

an idea but gets

caught in a wad of

tangled breath

catch it in time

The word “waiting” jumped out at me.

*

What is this state of waiting? Why did Beckett call to me after Kate’s death?

This “in between” consciousness is an awareness, as Kate’s notes indicate, of being both here and not-here. Leaving one place and not yet arriving at another.

For Kate, it was a state between life and death. For me, it is a state between with-Kate and without-Kate.

I have found that I was ready for Kate to die. She was beyond ill for a significant period of time. The doctors kept hoping to stabilize her, but in the final months didn’t.

I knew she was going to die, and I was emotionally ready for the final act.

I was not ready, however, for her to be gone. Forever gone. Emotionally, I can only state that it is impossible. I cannot register that belief.

Like Estragon and Vladimir wait for Godot, I wait for Kate.

I can only believe that I will see her again, and this is an experience different from my expectation.

Perhaps this is a form of magical thinking, as Joan Didion made widely famous. But I don’t think so. Didion kept her closets full of her late-husband’s clothes because “he’ll need them when he comes back.”

I don’t have that kind of expectation. I have relieved my closet of much of Kate’s clothes.

My expectation is existential, and I don’t think it will ever go away.

I am, I live, within a Beckettean structure. Perpetually waiting.

And I’m okay with that. The mysteries, and opportunities, it seems to be, are boundless.

*

I have now finished reading Waiting for Godot and Mrs. Dalloway. I would hesitate to say that they have anything in common except a strong uneasiness with certainty.

Beckett’s character wait and employ various strategies, mostly verbal, to fill the void of waiting. The plot of Mrs. Dalloway contrasts the planning and hosting of a party (held for no reason other than it be held) against a suicide.

Beckett’s characters also contemplate suicide, and they seem ready to follow through with the act, but they want for rope.

Kate, I want to be clear, had no desire for death. No desire to let go of her life. The suicide option explored by Beckett and Woolf is a rhetorical option.

To live or not live. To choose to turn into life or turn away from it.

Kate chose always to turn into it. To have parties for no reason. This also meant, however, that she grasped the deep details of her life, and she knew it was ending.

Her approach, however, drove her not to attempt to summarize her life; or to turn her thoughts obsessively to the past; instead she focused determinedly on the meaning of every moment. Making new meaning out of every future moment.

Or in the words of a title of a book that became important to her: Enjoy Every Sandwich (by Lee Lipsenthal).

I often think of her in the title of a short story (about a woman dying of breast cancer) by Thom Jones: “I want to live!”

An example. As Kate lay dying in the back room of our house, where she died, I noticed that the poppies had bloomed in our front yard. More precisely, one poppy had bloomed, our first. I picked it and brought it to her. She smiled. Her face formed an, Oh!

It was the last pleasure I was able to give her. She died three days later.

Let the poppy represent the party. Life is to be lived; therefore, enjoyed. One waits for the mystery of what is going to happen next.

*

But let’s also talk about the absurdity of waiting.

On May 18, 2012, the Friday before Kate died (on Wednesday, May 23), she had two appointments at the Sunnybrook Medical Centre. The medical team had helpfully booked both procedures on the same day, so she wouldn’t have to go back and forth from home. However, one was booked for 8:30 in the morning, the other at 3:00 in the afternoon.

Which meant we would be at the hospital all day, especially since the procedure in the afternoon (chemotherapy) was sure to be delayed, which it was (by about 90 minutes).

On top of that, Kate could no longer walk. She could shuffle a few feet, but she could not climb stairs, and there are two dozen stairs between the sidewalk and our front door. So we had to hire a private ambulance company to carry her down the stairs and take her to the hospital. Then at the end of the day, we had to call them to pick us up, bring us home, and carry Kate back up the stairs.

Ultimately, this meant we left home at 7:30 in the morning and didn’t return until 7:30 at night.

Which meant we spent 12 hours together, mostly waiting.

I remember that time fondly, as it was our opportunity to say good-bye, and much else, and we were never alone again after that.

We were waiting for procedures, but more simply we were “being together,” and I told her that I wished that that moment would last forever.

I wished that time would simply stop.

I could wait for Godot forever. I needed nothing else to be complete.

When we saw the results of her blood work that afternoon, we knew there was going to be no recovery. She said, “I guess this is it.”

I want to go on, I can’t go on.

She asked me what I feared most. “Chaos,” I said. I was afraid that my life would spin out of control. Events would happen that would be beyond my ability to manage.

Of course, chaos did happen. Absurd things happened. I control them by calling them absurd, instead of allowing them to send me into a tornado of rage.

The day after Kate’s funeral, I made contact with the pay and benefits clerk at Kate’s employer to begin the death administration. She would be pleased to help me, she said. She just needed to get Kate’s personnel file before she could begin. A week later, I called back and she hadn’t located the file. A week later, I called back and she hadn’t located the file. A week later, I called back and she hadn’t located the file, so I escalated the issue to a manager and within 20 minutes they had located the file.

The private ambulance had cost $190 one way and $380 return, which I paid in advance by credit card. A week after Kate’s death, I called asking for my receipt. They patched me through to the accounting department, who told me a receipt would be sent. Two weeks later, no receipt, I called back and again they told me a receipt would be issues. Two weeks later, no receipt, I called back and they remembered me. We will send a receipt, they said, and a couple of days later it arrived.

“Waiting is the hardest part,” is a lyric from Tom Petty.

“Waiting for a superman,” is a song by the Flaming Lips.

The administrators of Kate’s pension sent me a letter offering condolences at the loss of my spouse. They also enclosed a form that I was apparently required to complete and get notarized by a lawyer, proving that I was indeed her spouse. Directions for the form included the statement: “Check I WAS MARRIED TO THE DECEASED if you were legally married to the deceased.”

You can’t make shit like this up. I don’t know how lawyers sleep at night.

It hadn’t occurred to me that the chaos that would follow Kate’s death would be the absurdity of administration. Yet, I am caught, enmeshed in it.

As Kate was dying, the doctors tried to get more nursing care to come to our home. But in order to get “shift nursing,” one must first file a claim through any insurance you have. I filled out the paperwork, and the doctor signed and faxed it in. A week after she died, Kate received a letter from the insurance company that she didn’t qualify for nursing care.

These are not even all of the stories I have. They are a sampling.

Here’s one more. A week before Kate died, I knew she was dying. I knew it in my bones, although there was a minor hope that she would get a “chemo bounce,” and some extension of time. I didn’t expect it, and I busied myself rallying the healthcare team to step up their care of Kate in the home and pay more attention to her decline, which was changing daily.

Then the day before she died, the palliative doctor gave me a handout that listed “what to expect when someone is dying.” It listed a dozen bodily changes, most of which had already happened to Kate. The doctor then said he wouldn’t be surprised if Kate died that day. She lived for 24 hours.

I was told that the palliative doctors would manage her death. No one needs to be in pain, they said. But they failed to manage her death. A week before she died, I promised her I would leave no card unplayed. “It’s time to be all-in.” And I was, and I did. Because the health care team was unable to respond appropriately — in the time she had left.

Is “respond appropriately” the right phrase? Could it be “respond meaningfully”? Did they give her a meaningful death? I have to answer, no. Some individuals were helpful. I kept my promise to her; I did everything I could. The system, overall, however, failed; it produced absurd results.

For the final six weeks of her life, Kate received hydromorphine through a pump that she carried on a belt around her waist. The pump fed the drug, seven times more powerful than morphine, through a tube and a needle that was implanted in her abdomen. The needle needed to be moved to a new site every couple of days.

At the end of April, Kate spent five nights in the hospital. She checked herself in because she wanted more investigation of her pain. The pump that she used had been installed by the community care nurse that visited her at home daily. Once in hospital, she had to have the home-care pump removed, and a similar (but different) hospital pump installed. Not too big a deal, except when it came time to go home.

She was addicted to a powerful painkiller, and the hospital would not re-install the home-care pump. So she couldn’t be discharged until a home-care nurse could be secured to meet us at home. The first nurse suggested we wait overnight until the morning nurse made the arrangements. No, we said. She wants to go home. She’s been here five nights already. So I called the home-care line, and (long story short) three hours later we grabbed a taxi and met the nurse on our doorstep and had the drug line re-inserted.

I remind you. Canada. Single-payer health care. Two pumps. One patient.

When the doctor signed Kate’s death certificate, under “cause of death” she wrote two words: “breast cancer.” The truth is, it was so much more, and beyond description.

So have parties for no reason, and make of life your own meaning, because the bureaucracies of the modern world are going to do nothing but frustrate you. Grind your signifiers to dust.

*

About a month before Kate died, I wrote on a piece of scrap paper: “What we know? What we don’t know?”

I can see now that we were, then, in a period of waiting. Waiting for the treatment(s) to stabilize her. Waiting for the disease to return. We had been told it would. She had triple-negative breast cancer. It had already metastasized from the breast to the liver to the bone.

Her disease was incurable, and the medical goal was to hold it off as long as possible.

What we knew: it would come back.

What we didn’t know: when it would come back. Also, what would happen in the meantime.

When I scribbled those questions on that scrap paper, my heart ached for knowledge and stung with ignorance. I felt up against the void. Looking off-stage for Godot. Where is he? Is he coming? Tomorrow?

I scribbled those questions because I wanted to capture something of what it felt to be in that place.

Kate blogged about her experience with cancer from beginning to end. The experience enriched her soul even as it attacked her body. She wrote marvelous personal essays about topics of immense diversity. She wrote about what it was to be infected with a terminal disease, to live up against the void.

We repeated our catchphrases: enjoy every sandwich, live for the moment, nowhere to go, nothing to do.

We repeated that death comes for all of us, and none of us knows when. So why not approach every day with joy and anticipation?

Always have hope. Always laugh. Always take cream in your coffee.

To say we lived deeply is an understatement. To say not everyone was able to follow us on the path is also true. Some found Kate’s blog too much. Some found her honesty in confronting the void overpowering. Some turned away because life is really, really busy, after all. Really busy.

One of the questions that has repeated in my mind since her death is the difference between figurative and literal language. I am a person of metaphor. It comes easily to me, and I enjoy it, and it is a nurturing part of my personality.

Kate’s death put my metaphorical language under immense stress. Which is shocking to me. Because how else to express the profundity of the experience, except through metaphor.

However, the child psychologists advise talking to children about death in literal terms. The heart has stopped. The body has ceased to function. Don’t say she’s gone to sleep, because they the children may fear sleep. Don’t say she’s gone to a better place, because then the children may want to go there, too.

Then there is the overwhelming amount of logistics that I became responsible for. Not just the managing of the health care team, but the managing of the post-death rituals: the visitation, the funeral, the burial, the reception. Child care for the funeral and reception, is something someone else tried to insist I provide, but I said no. Enough already.

For the two weeks prior to Kate’s death and the two weeks afterwards, my life was overwhelmed with action: do, do, do. There was no time to reflect. No time to contemplate. Literal language provides the closest distance between two points, and I felt like Michael Corleone in Godfather II, giving direction because I could — and it was needed.

I mentioned this odd sensation to my psychiatrist, and he said: “He didn’t want the job either.”

A-ha! There is someone who understands the basis of a good joke.

And Kate would have got it, too. And that’s what I think is the basis of this cycling question in my mind about the figurative versus the literal.

What is real? And what is not? What do we know? What do we not know?

Someone who lost a child to cancer told me that she cannot read fiction any more. I said, I cannot believe in non-fiction any more. All that I see to believe in is language. I see no basis to believe in anything else.

Virginia Woolf’s famous subjectivity swims all through Mrs. Dalloway and it seemed perfectly sensible to me. The “realist” alternative is one exemplified by the form from the pension administrators. Sorry for your loss, but get a lawyer to prove that you deserve it.

Horrendous! Outrageous!

But it will all be better when Godot gets here. Don’t you think?

(Life is a tale of sound and fury, told by an idiot, signifying nothing.)

*

“Hope is the thing with feathers.” – Emily Dickinson

This is where Kate would want me to end, with hope, not pessimism.

Also, with feminism.

Too many -isms!

I have a stack of Kate’s books that I’ve promised to give Naomi, Kate’s daughter, when she turns 16. Gloria Steinem titles dominate.

But there’s also Kate’s MA thesis: “Labours and Love: Issues of Domesticity and Marginalization in the Works of Paraskeva Clark” (Condordia, 1995).

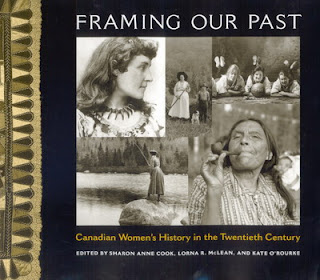

And Framing Our Past: Canadian Women’s History in the Twentieth Century (McGill-Queen’s, 2001), edited by Kate along with Sharon Anne Cook and Lorna R. McLean.

Domesticity and marginalization, I would write a tome on that, and Kate knew it. I married her and her kids in 2006, and my writing all but stopped.

Caring for her through cancer did stop it.

As caring for an ill child stopped Clark’s artistic production.

Writing this essay is part of the process of reclaiming literature and a mind reflective enough to write. It’s about moving out of the literal, opening my mind again to metaphor.

Kate would appreciate all of this, but she would also say: Don’t whine, do.

Get on with it. Being. Doing. Living.

Don’t miss what is right in front of you because you’re too anxious about something happening at some point in the future. Tomorrow.

When I was younger (really younger), I struggled with what was more important: life or art. In her memoir Dancing on the Earth, Margaret Laurence choose life. Oscar Wilde chose art.

Now, I couldn’t tell you what the conflict is about. Everything is integrated. How can art exist without the context of life? How can life exist without art?

Art as meaning, even if it’s a communication of the absurd.

I resist mysticism, but I must be honest. Kate was curious about death. She thought she was going somewhere. She thought there would be other dead people there. She hoped so. There were some people she’d lost and wanted to see again. I told her that I would see her again. That was a new thought for me. I felt it with a conviction that it must be true.

“That’s why we’re married,” she said.

For Kate, meaning was in connection with others. Like Mrs. Dalloway. Like the quest for Godot. Meaning was in connection with the other. What it was, though, was unknown and possibly unknowable. But it was something that must always be quested for.

For her memorial service, I asked people to bake and bring cakes. I had no idea how many would come. I didn’t know if we would have too little or too much.

I wanted to put out the challenge and live with risk.

What happened was the miracle of the cakes. Sixty-five cakes! All individually baked and decorated.

A party. The arrival of Godot.

*

Post-script

Two weeks after Kate died, I went to my local bank branch to cancel her bank card and VISA. I had to bring a copy of the proof of death and her will. Six weeks later my VISA statement arrived and Kate was still on it. I called VISA and they said that her account was still active. I cancelled it, I said. I went to the bank, and they cut her card in half and I signed a form. (A form! Is that itself not proof enough?!) The branch can’t cancel her account, the VISA lady said. Her account is still active. Do you want to cancel it? Do you have her card? No, I replied. They cut it in half six weeks ago when I cancelled her account. Her account is still active, she said. Do you want to cancel it? Yes, I said. Do you want to cancel yours, too? No, I said. You just give in, don’t you? You just give in to the literal and do whatever is required. Kate is dead, I wanted to say, to provide the conversation its context — and I, as far as I know, am still waiting for that release.

I’m heading to the book shelf now to pull down Flann O’Brien’s The Third Policeman.

I’m tempted to ask for the rope, but the hope imperative intervenes.

The question is, To be or not to be….

Whether ’tis nobler in the mind to suffer

The slings and arrows of outrageous fortune

Or to take arms against a sea of troubles

And by opposing end them. To die, to sleep–

No more–and by a sleep to say we end

The heartache, and the thousand natural shocks

That flesh is heir to. ‘Tis a consummation

Devoutly to be wished. To die, to sleep–

To sleep–perchance to dream: ay, there’s the rub,

For in that sleep of death what dreams may come

When we have shuffled off this mortal coil,

Must give us pause. There’s the respect

That makes calamity of so long life.

For who would bear the whips and scorns of time,

Th’ oppressor’s wrong, the proud man’s contumely

The pangs of despised love, the law’s delay,

The insolence of office, and the spurns

That patient merit of th’ unworthy takes,

When he himself might his quietus make

With a bare bodkin? Who would fardels bear,

To grunt and sweat under a weary life,

But that the dread of something after death,

The undiscovered country, from whose bourn

No traveller returns, puzzles the will,

And makes us rather bear those ills we have

Than fly to others that we know not of?

Thus conscience does make cowards of us all,

And thus the native hue of resolution

Is sicklied o’er with the pale cast of thought,

And enterprise of great pitch and moment

With this regard their currents turn awry

And lose the name of action.

—Michael Bryson

————

Michael Bryson, a frequent NC contributor, has been reviewing books for twenty years and publishing short stories almost as long. His latest publication is a story “Survival” at Found Press. Last fall he published an e-version of his novella Only A Lower Paradise: A Story About Fallen Angels and Confusion on Planet Earth. His other books are Thirteen Shades of Black and White (1999), The Lizard (2009) and How Many Girlfriends (2010). In 1999, he founded the online literary magazine, The Danforth Review, and published 26 issues of fiction, etcetera, before taking a break in 2009. TDR resumed publication last fall and is once again be accepting fiction submissions. He blogs at the Underground Book Club.

See also “Kate’s Song” written by Brooke Sturzenegger and Kate’s flikr albums.

And for the close, here is Warren Zevon’s appearance on Letterman where he said “enjoy every sandwich” —

What a brave, important piece of writing. Thank you for bringing it to NC.

This essay peeled back my skin and changed the course of my day. Though it may be dangerous to believe, I still feel like I know Truth when I hear it (or read it). This account of your loss and grief is Truth. Thank you for writing this very sad, beautiful, potent essay and sharing it here.

Thank you, Michael. My shirt caught more than a few tears as I read this. I had followed Kate’s blog and was struck by her raw and honest writing — and, particularly in the context of such physical pain — its beauty. The same is true here. Thank you, too, for a few laughs. I hope to remember to greet the next cemetery I pass with the same enthusiasm. Hello, dead people! And hello to those of us who remain.

This is so beautiful and sad and full of love. Thank you for sharing this, Michael.

These are very powerful pieces of writing. Beyond sad. At some point I hope the children will read them.

The cliche is accurate — I am so sorry for your loss.

Thank you, NC.

Moving and honest. Comforting in some brutal way.

I was talking to Godot yesterday, Michael — you know, trembling writer to imposing, steadfast metaphor — and Godot in full metaphoric (not all that attractive) attire mentioned your name and talked adoringly about Kate’s life and memory. Godot told me you got it right, Michael. Perfectly. Impossibly. Painfully. Absurdly. Now, if the Divine would only read your profound essay. But then the ludicrous, preposterous scheme of things might start to make sense, and we wouldn’t really want that, would we, my friend? We do have our scribbling, after all, and that is enough for now, for our perfect, impossible, painful, absurd now…

Yes, J.J., and thank you. You’ve summarized my summary! Tally ho!