The Spiritual Pilgrim Discovering Another World (Woodcut) 17th Century

The Spiritual Pilgrim Discovering Another World (Woodcut) 17th Century

.

Athanasius Kircher: Harmonia Nascenti Mundi (1650)

Athanasius Kircher: Harmonia Nascenti Mundi (1650)

“When one analyses the pre–conscious step to concepts, one always finds ideas which consist of ‘symbolic images.’ The first step to thinking is a painted vision of these inner pictures whose origin cannot be reduced only and firstly to the sensual perception but which are produced by an ‘instinct to imagining’ and which are re–produced by different individuals independently, i.e. collectively… But the archaic image is also the necessary predisposition and the source of a scientific attitude. To a total recognition belong also those images out of which have grown the rational concepts.”

Wolfgang Pauli – ATOM & ARCHETYPE

.

Sea Time

I

n my twenties, as a merchant marine crossing both oceans and several seas, I spent hours at the rail watching the mysterious relationship between sea and sky. At times they existed peacefully, like sleeping lovers, fused, with no defining horizon. Afloat in seamless space, I glimpsed the plenitude of timelessness. More often, water and air colluded in creating spellbinding iterations of light. Most incredible were their sudden declarations of war. And with each shift of mood between them, I identified a corresponding one in myself so that concentrated thus, in this floating world, the only secure anchor was the observing eye that contained the image linking both worlds.

Crossing from San Francisco to Vietnam, by way of the Philippines, in late August, 1965, the first week out held the kinds of wonders one glimpses when the waters are calm and the sky responds with amplitudes of light at all hours dancing on its surface. Sea-spouts rose between mothering ocean and covering air, ladders for sunlit angels at mid-day, shadow columns supporting an invisible Parthenon at dusk. Following seabirds in our wake. Flying fish leaping into plain sight where our bow sliced the water. And then suddenly, in the middle of the Pacific, the mood changed. Wind driven clouds drawing strength from the water set up a fierce exchange of disorienting forces. We spent the next two weeks with hatches battened. The storm that raged around us was Shakespearean, the kind that battered ships and scattered sailors to unknown islands. It had the most startling effect on me, one I couldn’t explain. Only to observe that it drew me more powerfully than all the days, sights and moods that had come since we weighed anchor in Alameda, and passed under the Golden Gate.

Every day, at the height of turbulence, as the S.S.Esparta plunged and rolled, I made my way past the spinning cylinders of our twin screws to the end of the shaft alley. Where the alley narrowed, and the shafts disappeared a narrow metal ladder bolted to the bulkhead extended straight up. I climbed from my engine room station five stories below deck to a small hatch at the top. It was the only one on the ship unsecured from the outside. I held its weight open slightly to gauge the strength and direction of the wind, then, when I judged it safe, climbed out. The hatch opened on the fantail, behind the paint locker, which afforded minimal protection. Holding the rails on the side of the paint locker, I made my way to the stern and held on for dear life. Twice a day, for ten or fifteen minutes, I stood there as sky-scraper swells lifted our twin-screw refrigerator ship like a bathtub toy. It rose so high on the swell I could see the top of mountain ranges, Appalachians, Ozarks, Adirondacks—shapes carved in stone—for an immutable instant, before we fell. The descent was as steep as it was sudden. At the bottom, nothing existed but the trough, and the black white-veined wall liquid marble that loomed like a canyon overhead.

Those who spend time at sea, out of sight of land, can tell you that there is a quality in which time and space, inner and outer, dissolve, and that the experience extends beyond becoming conscious of a particular moment to becoming consciousness itself. On the ship’s fantail, I did not so much witness the spectacle as participate in it. From that point of view, I apprehended the world through feeling and intuition, and the images they provided as guides, contained by the observing eye that links the individual psyche to the word soul.

.

Je Suis Quelque Je Trouve

According to Aristotle, we gain knowledge not by talking about horses, but by direct contact with a particular horse; feeling its material qualities rooted in our sense-perception leads to an intuitive grasp of the universal in the particular, its horseness. Feeling and intuition as a way of knowing build on a degree of participation in what it is to be the other. Aristotle further observed that our souls shared a “nurturing” aspect with all living things. This may speak most pointedly to the idea that as infants we learn to read the world through what we see mirrored back at us in those responsible for our nurture. This early “mirroring” experience may explain why intuition, the handmaiden of inductive reasoning, remains a relevant epistemological tool. Its feel for correspondences and probabilities has survived to the present day. On the other hand, early mirroring may not inoculate us against advances in technology; fractal geometry, spectroscopic measurements, nanophotonics, particles that exist for femtoseconds, three dimensional and holographic imaging—information systems that break down the object of knowledge into unrecognizable components. What happens to “knowing” when we deconstruct the mirroring face of nature, and it becomes possible to understand a horse, or a storm at sea most efficiently as a series of algorithms?

Mind Map: The psychology of C.G. Jung Walter-Verlag (1972)

Mind Map: The psychology of C.G. Jung Walter-Verlag (1972)

C.G. Jung posited that we get to know our world through four basic functions, two of which are primary and two supportive. On the (primary) vertical axis “thinking” and “feeling” are in opposition, while on the (supportive) horizontal axis “sensation” and “intuition” occupy opposite sides. Each of the four provides a specialized stream of intelligence. According to this paradigm, one function on each axis develops at the expense of the other; one becomes “dominant” and the other “inferior”. Extreme imbalance can create serious issues. If a culture elevates “thinking/sensation” and diminishes the importance of “feeling/intuition”, then the ability to incorporate value and connection as essential components of knowledge may diminish or even atrophy. One can’t underestimate the importance of nurture in the formation of empathy. Or empathy as the engine of cognitive development. When mirroring nurture is replaced by video games, and cognitive development, harnessed to unreflective information gathering, the ability to read each other deeply becomes grotesquely distorted or ceases to exist; the inner landscape gives birth to the outer landscape, and both will be a Waste Land.

.

Navigating the Numen

Quantum prophet Werner Heisenberg concluded in that we cannot observe phenomena without effecting them. His work on a sub-atomic level indicated that the movement of matter/energy responds to our consciousness. He also noted that we could calculate the speed or position of a particle, but not both. At least in that arena, it appeared that enthroned analytical intelligence had reached the limits of measurement and calculation. After his pronouncement in 1927, we were left with probability rather than certainty in our ability to predict the behavior of the fundamental elements of our world.

On the other hand, his observation suggested a backdoor to Aristotle’s theory of knowledge, since we were once again participants in the field of activity, not simply witnesses. But just how could we apply our elusive understanding of sub-atomic particles to knowing the horse? Certainly the situation that exists on such a basic level must affect us globally. How does one participate in what one can’t see? Or could we enlist the imagination to bridge these worlds?

Einstein employed “thought experiments” as an essential part of his process. In order to formulate the problem he’d been thinking about, Einstein created a way to explore it visually. Here is a train moving past a station. I am both inside the train and standing on the platform. If there is a flash of light at the center of the car inside the train, I will see it at the same time from both points of view, but experience the event differently. From inside the car the flash will appear at the center. From the platform, it will appear to be moving to the rear of the car. This difference in perception of a simultaneous event, according to the relative position of the observer, though the speed of light remained constant, proved what Einstein called his special theory of relativity. As in a dream state, he’d had to see the event from both points of view at the same time. The exercise invites the imagination (which one might argue already operates according to the laws of special relativity) into a participatory experience.

Einstein’s waking reveries allowed him to use his complete sensorium to experience the operations of his imagination as in a lucid dream. We respond differently to dream images that arise autonomously in sleep as if from a separate intelligence. Often there’s no waking memory of what’s been seen under these conditions. Many dismiss what they remember as fragmentary or irrelevant. For others, the intelligence embedded in these autonomous images that flesh our dreams opens the doors of perception. Einstein spoke reverentially of intuition as a guide to this process.

Developing a relationship with the intelligence that creates dreams and reveries requires finesse. An attitude of trust deepens the connection. As in any relationship, this is usually based on past experience of the benefits, and our willingness to accept a degree of uncertainty. Fully grasping the content of a given dream may be like trying to know both the speed and position of an electron at the same time. A mathematical impossibility. On the other hand, we can evaluate the truthfulness or intention of the image- and symbol-forming function only when we recognize its psychological products as facts, demonstrable and undeniable.

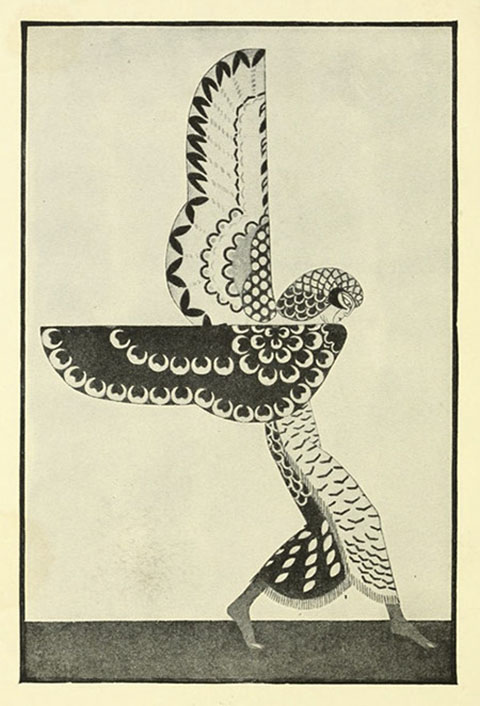

Paul Klee: Angelus Novus (1920)

Paul Klee: Angelus Novus (1920)

In my practice as a psychotherapist, I encounter this repeatedly in a variety of ways. Recently, my twenty-five year old client, Nick, an artist of considerable talent, related that I appeared in his dream in a wheel chair. It was at the opening of a solo exhibition of his work. He welcomed me, told me how glad he was that I had come, then asked how I was feeling. I replied: “The world is dangerous. The world is thoughtful. I’m all right.” The words resonated deeply for me. They summed up what, in fact, I hoped to model and convey to him in the course of our work. Understood in this way, the dream remains a concrete visual reference point and may be viewed as a psychological fact. A Memphite Tablet from pre-Dynastic Egypt, 5,100 years ago, tells us the creation of the world and everything in it issued from Ptah’s invisible heart-thoughts which materialized in his spoken word. “Every divine word has come into existence through the heart’s thought and tongue’s command…”

Thought takes shape in the dark, becomes visible to the mind, before it incarnates in material form: so I read the message of Paul Klee’s Descending Angel. The same one I hear in my client’s dream:

The world is dangerous

The world is thoughtful

I’m all right.

Problems arise when we find ourselves beyond the ability of the imagination to form a picture of thought. The Higgs-Bosom “God Particle” in quantum physics couldn’t be seen, but was intuited in 1960 as necessary to explain sub-atomic behavior. Forty years later its existence has been tentatively confirmed by the CERN accelerator. In 1930 Nobel Laureate Wolfgang Pauli expressed the hope that he would live to see the invisible “thought” he named the neutrino. It became visible in 1956 at a nuclear reactor on the Savannah River. Pauli died in 1958, two years later, without seeing his offspring. Today the neutrino is thought to be essential to the cohesion of particles, but is unconstrained by any of the laws that govern them; lacking an electrical charge, neutrinos pass through great distances in matter without being affected by it. They leave no footprint. Put another way, the neutrino remains unimaginable.

.

The Descending Angel

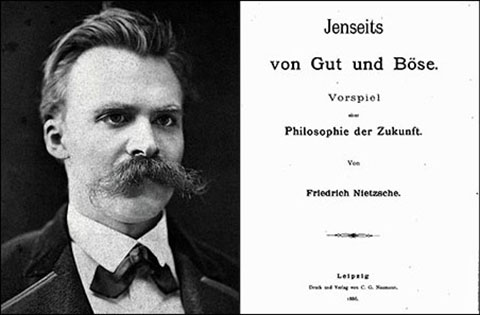

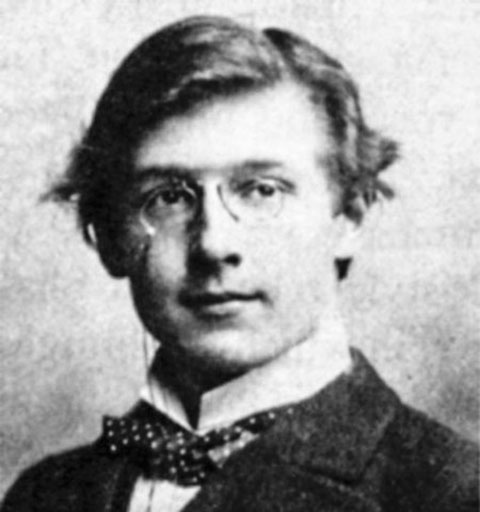

At twenty-four, Austrian-Swiss theoretical physicist Wolfgang Pauli (1900 – 1958) had established “The Pauli Exclusion Principle” that revealed the structure of matter and predicted the death of stars. He went on to discover the fourth quantum number and the theory of “spin” which explained the way electrons behaved inside an atom, calculated the hydrogen spectrum, and posited the existence of the neutrino. In spite of these achievements, the Nobel Prize genius spent much of his life in quantum physics desperately unhappy.

The Hubble: Colliding Spiral Galaxies

The Hubble: Colliding Spiral Galaxies

Pauli worked closely with Neils Bohr and Werner Heisenberg to formulate basic quantum theory as part of the Copenhagen Experiment in 1924. At that time, challenges posed by the hitherto unknown sub-atomic world were galvanized by discoveries like “complementarity”, the dual nature of energy as both particle and wave elaborated by Bohr in 1928. These waters were as uncharted as any crossed by Europeans in the 15th Century on their way to the New World. Physicists on the sub-atomic ocean also felt comforted close to shore on which the flora and fauna of the imagination provided a template. But even Einstein’s early “thought experiments” were less available to them as they sailed away from land into a featureless sea.

Without the imagination, and its productions, we are lost in deep space, directionless in utter darkness. Images, geometries, and analogies anchors us. How much more vivid deep space becomes if we compare it to a Paleolithic cave. Spinning galaxies and stellar explosions become the photonic equivalents of bison and wooly mammoth emblazoned on its walls. Physicist/astronomer Sir James Jeans wrote in 1930, the universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine. Mind no longer appears as an accidental intruder into the realm of matter; we are beginning to suspect that we ought rather to hail it as a creator and governor of the realm of matter…

Bohr Model Atom: UNSW, Australia

Bohr Model Atom: UNSW, Australia

We suspect mind and matter want to imagine themselves each mirrored by the other. In this way, they remain comprehensible to us. Pauli challenged that when he questioned Bohr’s visualization of the atom as a planetary system. The last thing he wanted to do was destabilize that structure, but what he observed in the behavior of electrons made it impossible for him to do otherwise.

Pauli’s assault on Bohr’s atomic theory was inadvertent and devastating. Central to the theory was the image of the atom as a planetary system with electrons orbiting a nuclear “sun”. Pauli found himself moving away from Bohr’s solar model. His attempt to answer the questions it raised led him to what became known as Pauli’s “Exclusion Principle.” One of the conclusions Pauli arrived at was the existence of “spin” as a property of the electron. The fact that electrons “spin” in opposite directions explained why they didn’t collapse in a heap. But sub-atomic “spin” was impossible to visualize. Gravity-based, planetary spin did not operate inside the atom. Still, Pauli’s “spin” accounted for so much. Along the way, it dissolved any possibility of an inert core (sun) at the center of orbiting electrons. By 1925, it was clear that Bohr’s model of the atom could no longer be sustained.

The atom had become unimaginable.

![FLUDD Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris [_] historia, tomus II (1619), tractatus I, sectio I, liber X, De triplici animae in corpore visione.](https://numerocinqmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/FLUDD-Utriusque-cosmi-maioris-scilicet-et-minoris-_-historia-tomus-II-1619-tractatus-I-sectio-I-liber-X-De-triplici-animae-in-corpore-visione.-705x1024.png) Robert Fludd: Utriusque Cosmi Maioris Scilicet et Minoris, Tomus Ii (1619).

Robert Fludd: Utriusque Cosmi Maioris Scilicet et Minoris, Tomus Ii (1619).

Arthur I. Miller’s book, 137, Jung, Pauli, and the Pursuit of a Scientific Obsession, describes the reaction of Pauli and his colleagues to the loss of this image. Visual support for atomic theory had provided a concrete link to shared experience. In its absence, the void beckoned. It triggered depression in Pauli, and created anxiety in his colleagues—especially Bohr. They tried to comfort each other. Pauli expressed his hope that eventually quantum theory would make sense of these ideas. “Once systems of concepts are settled,” he told Bohr, “then will visualizability be regained.” (62)

Pauli moved forward even as he grieved over what had been lost. The products of his own formidable intelligence haunted him. As he would say about his notion of the neutrino: “I have done a terrible thing. I have postulated a particle that cannot be detected.”

Aware that imagination was giving way to numbers, Einstein wrote, “There is no logical path to these laws; only intuition, resting on sympathetic understanding of experience can reach them.” He was talking about the only way he knew to glimpse “the ‘pre-established’ harmony of the universe.” (93)

Wolfgang Pauli

Wolfgang Pauli

With the collapse of Bohr’s solar model, atomic physics seemed to lie in ruins.

Arthur Miller writes about this turning point in intellectual history: “It was time for atomic physics to move on from trying to visualize everything in images relating to the world in which we live.” (63) Heisenberg put the fine point on it when he suggested that as scientists, and perhaps as a species linked by an inter-connected field of consciousness, we had moved into an area of nature that defied imagination.

.

Fish Talk

Frida Kahlo: Sun and Life (1947)

Frida Kahlo: Sun and Life (1947)

Gott ist tot, announced Nietzsche in “The Gay Science” in 1882. On the centennial year 1900 Freud’s “The Interpretations of Dreams,” revealed a hole in consciousness full of hidden meaning, dark fears and desires, repressed instinctive material. What we walled off in order to protect civilization, had spilled from the divided Victorian psyche as Mr. Hyde, Frankenstein, Dracula, and Jack the Ripper. Almost unnoticed, gods from Olympus, Saini, Ararat, Meru, Kailish, Machu Pichu, Zion had fallen into the cultural unconscious. By 1929 C.G. Jung observed that

the gods have become diseases; Zeus no longer rules Olympus but rather the solar plexus, and produces curious specimens for the doctor’s consulting room, or disorders the brains of politicians and journalists who unwittingly let loose psychic epidemics on the world. (Introduction to “The Secret of the Golden Flower.”)

We had swallowed our mythological offspring. No longer to be summoned by name, the archetypal energy the gods represented were now expressed in a variety of somaticized disorders—whole Pantheons translated into stress-related clinical symptoms.

Gertrude Stein made clear that the rate of change in the 20th Century was greater than in all of those preceding it. The speed exerts a G-Force equivalent to that which affects astronauts in rockets attempting to burst free of earth’s atmosphere. We have yet to understand the long range effects, how this may change us as a species. But it is also true that the function and structure of the deep psyche hasn’t changed since our ancestors painted images on rock walls where the sun never shines. The cave of our unconscious and its content is as rich in imagery as those at Lascaux and Trois Freres. We visit this Paleolithic space in dreams. Mythic figures come and go, accompanied by emotions that make our waking ones pale.

Vestiges of these immemorial images survive in comic books, cartoons, video-games, niche marketing campaigns and cinematic special effects—simulations of awe. Certain image rich fairy tales and cartoons stir the unconscious. I am thinking of “The Last Unicorn,” “The Dark Crystal,” “The Triplets of Belleville,” the Slavic “Baba Yaga,” and Hans Christian Anderson’s “The Little Mermaid.” Archetypal figures emerge in apocalyptic high-relief like the emotionally compelling robots in films like “Blade Runner” and “The Terminator,” or the perplexing amalgam of human and machine called Darth Vader, or in disguise as Robin Williams in “The Fisher King.”

Perhaps the richest archetypal figure for me is the original wounded Fisher King, Amfortas, portrayed by the 11th Century minnesinger Wolfram von Eschenbach in his romance, Parzival. Once the custodian of the Holy Grail, Amfortas has violated his role by doing battle with a Saracen knight whom he kills. But he is wounded and lives unhealed, in perpetual pain, most severe when in the presence of the Grail. It is eased only when fishing. Amfortas, whose name means “without strength”, must wait for Parzival to arrive in order to heal him and restore what has become a Waste Land.

Wayne Atherton: Fish Map #3

Wayne Atherton: Fish Map #3

Amfortas is every fisherman. I imagine that he may have been internalized along with all the other defrocked archetypes and now exists inside of us. I hope that for all our sakes he continues to ease his pain by fishing interior depths. And what happens if he feels a tug on the end of his line? I wonder what he will bring to the surface. In stories by the brothers Grimm, and Alexander Pushkin, it is a talking fish.

In Pushkin’s poem, “The Tale of the Fisherman and The Fish” (1835), an impoverished Fisherman catches a golden fish in his net who begs for his life. The Fisherman, moved by his plea, throws him back. But the Fisherman’s Wife, after hearing about this encounter, sends her husband back to ask the fish to grant a wish in return. The fish grants the Fisherman’s first wish of a house to replace their hovel. Not satisfied with the house, she sends her husband back repeatedly with an increasingly grandiose list of wishes. Along the way, his wife becomes a queen, and then a tsarina and finally the Ruler of the Sea in order to subjugate the fish to her will. In an earlier version of this folk tale collected by the brothers Grimm and published in 1812 as “The Fisherman and His Wife,” the fish, a flounder, claims to have been an enchanted Prince, but offers to grant the fisherman a wish in return for his life. The wife in an ongoing series of demands moves from a hovel to a castle surrounded by untold wealth. Her queenly crown is replaced by a Papal miter, and then the unvarnished demand that she become God. At that point the fisherman and his wife in both stories are cast back down into their original condition.

There are a couple of minor but noteworthy differences in these two versions. Pushkin describes a gold fish while in the Grimm tale it is an enchanted Prince turned into a flounder. One Fisherman mistakes the gold color for the promise of material wealth. The other one is blind to the omen that he is destined to flounder. Both fail to discriminate between the visible fish as a magical wish-granting function, and the unseen power it draws on. In spite of the fact that both couples have been living on what they draw from the sea, they make no conscious connection to what lies beneath the surface. With every new demand to grant a wish, the sea becomes increasingly disturbed. The princely flounder leaves a trail of blood as it sinks to the bottom. One can’t help but feel for the wounded fish, and the increasingly bloody body of water that shelters it, any connection to the submerged source of abundance eclipsed by the greed of the fisherman and his wife.

Impoverishment and greed remain at the end what they were at the beginning. No one is changed by the narrative—except perhaps the reader. Andersen and Pushkin have given us a cautionary tale: those who mistake the talking fish for the source of its power, are in the end impoverished.This disconnection between the fish and the fisherman may be more important than what appears to be the moral center of the tale.

What does this mean for the Fisher King?

Will we grow numb to his wound, and lose connection to him in the deep psyche?

If we do, will he simply ride metatstaically through our liver, kidneys and lungs?

On the other hand, if we invite him into our hearts, might he fish up a new image to reconnect us—or a quantum fairy tale?

Reframing the Questions

Owl Mobbed By Other Birds, England, Beastiary, (1250)

Owl Mobbed By Other Birds, England, Beastiary, (1250)

There has seldom been a more moving example of the Fisher King than Wolfgang Pauli. Once the keeper of the Grail, now disconnected from it by the unhealed wound of his own devising, few have fished more passionately for what is hidden beneath the surface. At a time when physics and psychology were undergoing a sea-change, the boundary between them ever more unclear, Pauli wanted to reconcile mind to matter as a unified field. Perhaps we can best grasp the spirit of this period in astrological terms where the imagery describes the movement of the equinox as it shift from Pisces to Aquarius. In Pisces we swam like fish in the ocean of the unconscious. As Aquarians, we will hold the amphora dispensing the element that once contained us. Caught in the transition, Pauli sails into the unimaginable.

Let us say, to extend the Arthurian metaphor, that the loss of the imaginal function in Pauli’s physics was the equivalent to being disconnected from the Grail, and to its abundance. Quantum Knights of the Round Table were stunned by what they faced, the emptiness. They understood that to reconcile gravity to spin (reclaim the Grail) required imaginal equivalents, but that these wouldn’t happen overnight. For the time being, they could only express their ideas as equations. Pauli, the Fisher King, confided in Werner Heisenberg: We must adjust our concepts to experience.

Pauli stood resolutely at the stern with his line in the water. He became such an exacting critic of his peers floundering theories he became known to them as “God’s whip.” The failure of the imagination to express ideas remained an unhealed wound.

His personal life, too, went into a downward spiral. In 1927 his mother, Bertha, a brilliant journalist, poisoned herself in response to his father’s desertion following an extra-marital affair. Pauli’s marriage to a cabaret performer proved stormy and short lived. Back in Zurich, he went on drinking binges. His forays into the bars became increasingly violent and he began to argue with colleagues at the university. He might easily have been confused with Fredrick March in the hit movie of 1931, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Pauli may have started off as a Gold Fish at twenty-four, but at thirty, like the Princely Flounder in Grimm’s fairy tale version, he sank to the bottom trailing blood and the invisible neutrino.

In danger of losing everything, he sought help from C. G. Jung, whose vision of the collective unconscious mirrored Pauli’s understanding of the quantum universe. The relationship between the conscious and the unconscious in analytical psychology was analogous to that of particle and wave in nuclear physics. Working with Jung, Pauli recovered the application of his powerful imagination in the existence of the archetypes. These constellated patterns of energy could be expressed in physical form. Pauli used them to reclaim the sense-experience that had been lost to quantum physics.

Through the language of symbols that emerged in his dreams, Pauli once again harnessed the image-making faculty to his formidable analytic abilities in mapping out new terrain, one shared by science and psychology. It was as though someone had whispered in his ear, “What ails thee?”

.

Briefly Mapping the Terrain

In Bronze Age cultures a temenos indicated a place apart, a sanctuary or sacred grove dedicated to a god. Represented archetypally as a circle squared, it is repeated architecturally in the traditional plaza—a square where (usually) four paths lead to a circular fountain at the center. Jung found the form represented universally in spiritual iconography as the Mandala. A symbol like the temenos is comparable to the neutrino. But its extension into the physical world is preceded by its existence as a psychological fact. Lacking an electrical charge, the neutrino moves through matter without creating a ripple, but holds it together.

Seal of Solomon

Seal of Solomon

My client Perry, a charismatic fifty year old man, went into a tailspin when suddenly abandoned by the only women in years to capture his heart. In our sessions his voice trembled, he became tearful or angry. Then one day he appeared for our session composed, and presented a dream. He found himself on a rock ledge facing a cave. A green curtain covered the entrance. As he watched, a face formed in it, a mouth and eyes. He parted the curtain. It wasn’t damp inside, but warm, the air fragrant. In the middle stood a fountain with water streaming down four staggered round bowls into a square basin. When he stepped out again, the face in the curtain announced: “I’m here.”

Parting the veil, Perry had discovered the temenos within himself. It continues to inform him today. Though visible to no one else, he can enter and leave it at will. Perry now says that he goes there when he wants to collect himself. Pauli’s apprehension of the neutrino, and Perry’s encounter with the temenos, were experienced by senses interior to those we use when awake. The absence of a visible image left Pauli uneasy. How could he fully know what he couldn’t see, even guided by his profound intuition. As Gertrude Stein pointed out after returning to Oakland, CA, and finding her childhood home gone: there is no there there.

Symbols like the temenos that bridge inner and outer worlds convey a comforting sense of intention. The naked intuition of the neutrino, on the other hand, alludes to a darker, impersonal mystery. In his work with Jung, trolling the waters of the unconscious, Pauli found his way back to the symbol-forming intelligence. The man who stripped sub-atomic physics of visual equivalents, fished up an image that links deep psyche to the creation of stars. It surfaced, like a talking fish, during his early years of dream analysis with Jung, but in this fairytale took the form of what Pauli called The World Clock.

.

The Invisible Number

Pauli’s focus on dreams drew him into the mystery of archetypal representations and their transformative power; trolling these waters eased his pain. It also strengthened his conviction: the intelligence embedded in the unconscious, not logic, connected us to what Einstein called “the ‘pre-established’ harmony of the universe.” Ideas that knit the atom to the cosmos could be developed mathematically, tested in equations, but as mathematical formulae could never explain the mystery of consciousness, or account for intuition. As Miller tells it: “Jung’s theory of psychology offered Pauli a way of understanding the deeper meaning of the fourth quantum number and…went beyond science into the realm of mysticism, alchemy and archetypes.” Pauli continued to flesh out his ideas with the symbolic language of these traditions independently, and in consultation with Jung, for the next twenty-six years.

Edvard Munch: Jealousy

Edvard Munch: Jealousy

Pauli and Jung co-authored a book, The Interpretation of Nature and the Psyche, to probe the connection between science and psychology. In it they explored the notion of synchronicity, or “meaningful coincidence,” and its sub-atomic equivalent, “entanglement,” where two or more particles with nothing connecting them exhibit identical behaviors—what Einstein called, “spooky action at a distance.”

No better example of this phenomenon could be found than in what became known as “The Pauli Effect,” which was witnessed with some regularity by a number of people on various occasions over the years. When Wolfgang Pauli walked into a laboratory, test tubes shattered, beakers exploded, and objects fell off the shelves. There have been a number of theories put forth to explain this, among them his almost palpable stress-driven intensity, and an overly active pineal gland.

Synchronicity dogged Pauli’s footsteps.

Pauli’s mentor, Arnold Sommerfeld, discovered the number 137 as the value of the “fine structure” of light emitted and absorbed by atoms. Along with the fingerprint, or DNA of each wave length, 137 emerged as a dimensionless fundamental constant in nature, central to relativity and quantum theory and necessary to the existence of life. It is also the numerical sum of Hebrew letters in the word “Cabbala.” Pauli found the number resoundingly archetypal and linked to ancient wisdom traditions. Einstein and the Zohar employ “intuition resting on sympathetic understanding,” as a way to read the book of the world in number and symbol. 137, the constant of underlying unity was such a number, and perhaps a symbolic equivalent for the Holy Grail.

When questioned by a colleague as to what he might ask God if the opportunity arose, Pauli answered, “Why 137?”

On Friday, December 5th, 1958, Pauli collapsed while teaching, then complained of stomach pains. He was transported to the Red Cross Hospital in Zurich, where a friend, Charles Enz, who had accompanied him, noticed Pauli was agitated. When he asked why, Pauli indicated the number above the door. He had been placed in room 137, and announced to his friend quite accurately that he would not be leaving it alive. After the removal of a massive pancreatic carcinoma, on December 15th Pauli died in Room 137.

.

Ending on a Synchronistic Note

The Hubble: The Pillars Of Creation

The Hubble: The Pillars Of Creation

Given his interest in time, and obsession with the fine structure constant, Pauli felt his dream image of The World Clock was a visual resolution to questions he had harbored for so long, and captured the mystery of the unified field. It might have amused him to learn that according to the calculation yielded by the Hubble space telescope measuring the speed at which galaxies are moving, the age of the Universe, that is the time elapsed since the Big Bang, is currently calculated at 13.7 billion years.

.

Winding the World Clock

Wolfgang Pauli always felt incomplete as a scientist. Even though “The Pauli Exclusion Principle” revealed the structure of matter and predicted the death of stars, he might’ve been a visitor to the exploration that measures its conclusions in vanishing traces of light, and particles that exist for a femtosecond. String theory accounts for things otherwise unaccountable, like the teleological argument used by Thomas Aquinas to prove the existence of God. Pauli had spent his life in pursuit of a disembodied science that according to Heisenberg defied imagination.

Early in his career Pauli responded to the unimaginable by splitting in half. The professor who by day tail-walked quantum waves, turned by night into a dark figure who raged in bars and brothels. He might’ve split definitively had he not found a temenos in Jung’s psychology. It was already familiar. Pauli had earlier intuited an equivalence between the unconscious and the quantum universe: “even the most modern physics lends itself to symbolic representations of psychic process.”

Certain critics suggested Jung manipulated his subjects to produce the archetypal dream material. He took a pre-emptive approach to his work with Pauli by making sure the content of Pauli’s dreams was “…absolutely pure, without any influence from myself.” For this reason, when Pauli entered treatment, Jung assigned him to a fledgling student of his, Erna Rosenbaum.

During five months with Erna, Pauli retrieved hundreds of dreams. Jung found the symbols that appeared in them similar to those in Medieval Alchemy. Jung chose four hundred of Pauli’s thirteen hundred dreams for his research into alchemical symbolism in the modern psyche. Quite apart from Jung’s research, Pauli probed his own symbol production with detailed notes and illustrations. Included among these notes is a description of the “sublime harmony” he experienced followed his “great vision”: Pauli’s revelation of The World Clock.

As he predicted long ago to Bohr, once system and concepts settle “then will visual imagery be regained.” The structure in Pauli’s great vision is assembled to evoke consciousness as a process of interlocking geometries held in the mystery of the unconscious, which exists outside of space-time. Writing later of Pauli’s vision that arrived on the back of a blackbird (Hermes’ bird) on the wing, Jung says: “It seems to be an attempt to make a meaningful whole of the formerly fragmentary symbols, then characterized as circle, globe, square, rotation, clock, star, cross, quaternity, time, and so on.” He characterized the vision as proof of a “conversion.”

Jung used this “religious” term to indicate the depth of Pauli’s transformation: the wound that had divided his psyche was healed. This vision reconciled science and psychology, along with other formerly opposing elements of his personality, in a complex representation of cosmic harmony, the unus mundus.

Pauli wrote Jung from Zurich in 1938: “The relationship of these images is strongly affective and connected with a feeling that could be described as a mixture of fear and awe.

W. Beyers-Brown: The World Clock

W. Beyers-Brown: The World Clock

Pauli writes about emerging from his vision in a peaceful state. What moved his genius to significant discoveries in quantum physics was never accompanied by such a profound sense of well-being. Pauli tells us The World Clock brought to light “deeper spiritual layers that cannot be adequately defined by the conventional concept of time.” In that moment, he produced an image that was in itself, and through which he became, a vehicle for transcendence. Jung describes it as “a moment when long and fruitless struggles came to an end and a reign of peace began.”

/

Channel Fever

Channel Fever is a state of extreme agitation that afflicts seamen on their way into or out of the harbor. Settled on the beach one is anxious to get back to sea. Conversely, still in the channel returning from sea one can taste, see, and smell the beach. Observable symptoms: pacing the companion ways at night, painting valves and gauges in the engine room the wrong colors, compulsive masturbation and emotional lability. I recall watching an able-bodied seaman on a decrepit freighter spend an hour trying to heat a can of soup on a toaster. A more extreme case was the oiler who kept trying to go over the side while we waited for the pilot to take us into Port Newark. As though he might beat us there doing the back stroke. I ran into him a year later at the old Drum Street union hall in San Francisco. After a session with the union shrink, and a brief period on disability, he was again possessed by channel fever, and on his way back to sea.

Something turns inside out in those who spend days adrift in sea-time. Especially fishermen on the troll. Most seamen, when given the opportunity, will throw out a line. Few would have difficulty accepting the idea that the man next to him at the rail has heard a fish talk. Or admit that he had been recently talking to one himself.

Years after disembarking in Seattle on my return from Vietnam to a world I didn’t recognize, I discovered the writings of those who sailed the unconscious, an order of seamen who not only talked about or to fish, but to a range of invisibles. Jung cultivated relationships with figures in his reveries, dreams and reflections. Similar to Einstein’s “thought experiments, Jung called this practice “active imagination.” Both situations set up an interrogation of the psyche that allows the observer to engage the Other outside the constraints of space-time, to participate in what is observed like the man who is simultaneously in the train and on the platform.

Notable among the imagined figures Jung cultivated was Philemon, a wise old uncle who became over time Jung’s spirit guide. Many such encounters with archetypal figures can be found in Jung’s Red Book, a record of confrontations with his unconscious based on experiences between 1913 and 1917. It became the seed-bed of ideas he developed over the next forty-five years. In a reverie at the end of the Red Book, Philemon appears at Jung’s door with a gathering of dead souls and informs him: These were seekers and still hover over their graves. Their lives were incomplete, since they knew no way beyond the one to which belief had abandoned them.

Jung revised this discourse as Septem Sermones ad Mortuos in a private edition for friends. He later appended it to his autobiography, “Memories, Dreams & Reflections,” published posthumously in 1962, in which he also describes the occasion when the dead appeared to him in a reverie on Sunday, January 30th, 1916. It started with a restlessness that grew into a sense of other presences filling the room. “They were packed deep right up to the door, and the air was so thick it was scarcely possible to breathe. As for myself, I was all a-quiver with the question: ‘For God’s sake, what in the world is this?’”

In the last version of Seven Sermons to the Dead, Jung’s doorbell rings and he answers it to find the Gnostic sage, Basilides, who flourished in Alexandria about 125 AD. Basilides answers Jung’s question with the opening line from the Red Book:

The dead came back from Jerusalem, where they found not what they sought. They prayed me let them in and besought my word and thus I began my teaching.

Jung studied the Gnostic systems for analogies to the structure of the psyche. Basilides conceived of gnosis as light descending from an ineffable God to become entangled in progressively dense layers of matter. Light generated by the deep unconscious is broken into dreams at the threshold of mind and matter. Sparks of that light known to the mind are held in the heart. The Greeks called the soul-spark, synteresis, which Aquinas would later link to a “knowledge of first principles.” Today, symbols that capture its light, like a Mark Rothko painting, may be reduced to the size of a postage stamp.

US Postoffice: Mark Rothko’s Yellow & Orange (1965)

US Postoffice: Mark Rothko’s Yellow & Orange (1965)

At Jung’s door, Basilides declared: Hard to know is the deity of Abraxas.

In the earlier draft, Philemon tells us that Abraxas is a God mankind forgot, though he stands above the one they remember. If Basilides were at the door today he might say simply that Abraxas is hard to hold.

Basilides could be describing the quantum world when he tells us: Abraxas is effect. Nothing stands opposed to him but the ineffective; hence his effective nature unfolds itself freely. The ineffective neither exists nor resists.

Before Heisenberg’s Uncertainty Principle, there was Abraxas.

Abraxis Coin, Roman, (300AD)

Abraxis Coin, Roman, (300AD)

He is improbable probability, that which takes unreal effect. The forgotten god perfectly suited to a quantum world that defies imagination. The notion of scattered sparks of gnostic light may find equivalent in the scattered amplitudes of particle interaction in a quantum field. It is hard to explain the most recent advance of mathematical physics. But how does one visualize the Amplituhedron?

Basilides might say we could call it Abraxas. It is an all-inclusive geometric notion which is not built out of space-time, and described as a “multi-faceted jewel in higher dimensions” that encodes basic features of reality as “scattering amplitudes”?

Amlituhedron

Amlituhedron

Where in the face of unimaginable amplitude do we cast our net into the waters of the imagination? A quantum net constellated to hold the stars and the unseen properties of an entangled universe. A net of entanglements to reassemble fragments of scattered light.

Abraxas = the Neutrino.

.

The Pre-conscious Step

In my reverie, I am sitting in the crew mess, and feel the rush of channel fever. I itch for solid ground. But I can’t see the beach, except as a distant shore. I remember fifty years ago climbing the ladder at the end of the shaft alley to the open hatch behind the paint locker and pushing myself into the storm. Standing at the rail as the fantail rose and fell, I merged with what I saw, what links psyche to the word soul, to know the horse, or a storm as Aristotle suggests we know anything, by becoming it.

C.G.Jung: Philemon (The Red Book)

C.G.Jung: Philemon (The Red Book)

Even though I can’t see it clearly, I feel the ship that carries me coming into the channel. I consider raiding the “night lunch”, or heating a can of soup on the toaster but understand neither will address my hunger. I hunger to know what moves people to put a human face on transcendence, then die or kill to defend it. A hunger that verges on instinct. I hunger to be comforted by something greater than my hunger. In a world that defies imagination, I hunger for the reassurance of a fairytale.

I leave the crew mess. Standing at the rail on the bow, I scan what is ahead. The engines slow almost to a stop. We might be preparing for the pilot to come aboard, as we must before we can dock. He will take us in. The pilot knows the currents and shoals. But his boat is nowhere in sight. I wait, eyes closed. When I open them again I’m standing at the water’s edge holding a line. It appears I have caught and released a fish. The goldfish that pokes out of the water has Wolfgang Pauli’s face, complete with the square jaw tending to jowl. He tells me that he will grant one wish, and asks me what I want. I reply that I would like to pull up from the depths the answer to my most profound question, which I have not yet framed even for myself.

Ancient Roman Mosaic, (Israel): Fish

Ancient Roman Mosaic, (Israel): Fish

The Paulifish frowns, then declares he will do even better and instructs me on how to constellate a quantum-net to capture the theory of everything. I take mental notes, follow his directions precisely in drawing the plan.

When I get home, I find a pad and pencil, then draw what I remember, the directive voice clear in my head. I’m disappointed with the result. What I see on the paper looks like a newt.

I return to the shore. The Paulifish appears again. I describe to him what happened when I followed his instruction. “I ended up with a newt, not a net.”

He repeats my words, a newt, not a net. Shakes his head.

I protest again that I adhered exactly to his directions.

“You’re not even wrong,” he repeats his well-known response to a cowering student. Then laughs. “Newton’s net is not what it used to be. I’m talking about gravity. Highly over-rated in the scheme of things. Even a nitwit knows a newt is not a net.”

It’s not supposed to work this way, I tell him. This interchange between us is supposed to be richer, magical, a way of riddling existence.

He is somber, this Paulifish, nods. If there is something I want from him, I must say it and stop demanding he both ask and answer my question.

“Fair enough,” I agree.

Again that smirk.

“Ok,” I tell him. “I want a concrete image to reveal what I know so deeply it remains invisible to me.”

“Be specific,” he insists.

“I need a pilot to guide me to the harbor I can’t see from the ship in my mind. And to see the ship from the beach where I now stand talking to you.”

“That’s two wishes,” he yawns.

“I want to know the world again as once I did, in full color,” I blurt. “When I could be in two different places at the same time.”

Paulifish nods as best he can, considering he has no neck. He repeats the advice he gave to Bohr when his solar model for the atom went belly-up. Systems and concepts have to settle, he assured me. I will perhaps be able to visualize again what is necessary for me.

“That’s not good enough,” I protest. “What about my quantum net?”

Paulifish tells me it’s too late to discuss this today. I might come back tomorrow. Or, better, in a week. Meanwhile, I should remember his words.

“What are those?” I ask, as if it mattered.

“Keep your line in the water.”

Ouroboros

Ouroboros

—Paul Pines

.

Note One: From Synchronicity by F. David Peat

David Peat describes the physical characteristics of the clock following Jung’s in his book, Psychology and Alchemy.

Pauli’s Worldclock

Pauli’s Worldclock

There is a vertical and a horizontal circle, having a common centre. This is the world clock. It is supported by the black bird.

The vertical circle is a blue disc with a white border divided into 4 X 8 — 32 partitions. A pointer rotates upon it.

The horizontal circle consists of four colours. On it stand four little men with pendulums, and round it is laid the ring that was once dark and is now golden (formerly carried by four children). The world clock has three rhythms or pulses:

1) The small pulse: the pointer on the blue vertical disc advances by 1/32.

2) The middle pulse: one complete rotation of the pointer. At the same time the horizontal circle advances by 1/32.

3) The great pulse: 32 middle pulses are equal to one complete rotation of the golden ring. (p. 194)

…Jung identified the point of rotation of the disks with the mystical speculum, for it both partakes of the rhythmic movement yet stands outside it. The two disks belong to the two universes of the conscious and the unconscious, which intersect in this speculum. The whole figure together with its elaborate internal movement is therefore a mandala of the Self, which is at one and the same time the center and the periphery of the world clock. In addition, the dream could also stand as a model of the universe itself and the nature of space-time…

Note Two: Wolfgang Pauli and the Fine-Structure Constant By Michael A. Sherbon

Journal of Science (JOS) 148 Vol. 2, No. 3, 2012, ISSN 2324-9854 Copyright © World Science Publisher, United States www.worldsciencepublisher.org

Another interpretation of Pauli’s World Clock could be made comparing it to a basic yin-yang space-time model of brain-mind function describing hemispheric interactions [13]. Pauli associated the rhythms of the World Clock with biological processes (in particular the four chambers of the heart and its average rhythm of 72 beats per minute) as well as with psychic processes [14]. In Wolfgang Pauli’s visionary World Clock geometry the blackbird is a symbol for the “turning inward” at the beginning stage of alchemy and the messenger for the creative solar principle.

Note Three: Pauli & Jung: The Meeting Of Two Great Minds By David Lindhoff

Following the dream of “The House of Gathering,” Pauli experienced a waking vision that came to him with great clarity and left him with the feeling of “Sublime harmony.” He called it “The Great Vision.” The Text reads…

This vision of two cosmic clocks orthogonally related to each other by a common center challenges our rational prejudice as we contemplate the physical unrealizability of the construction of The World Clock. The image is a three dimensional mandala symbolically representing the structure of space and time, which have a common center point.

The empty center shows that there is no Deity within the symbol. Taking the vision to have collective significance, Jung observed that modern humans have the task of relating to the whole person, or the self, rather than to a god-image that is a projection of the self.

.

PAUL PINES grew up in Brooklyn around the corner from Ebbet’s Field and passed the early 60s on the Lower East Side of New York. He shipped out as a Merchant Seaman, spending August 65 to February 66 in Vietnam, after which he drove a cab until opening his Bowery jazz club, which became the setting for his novel, The Tin Angel (Morrow, 1983). Redemption (Editions du Rocher, 1997), a second novel, is set against the genocide of Guatemalan Mayans. His memoir, My Brother’s Madness, (Curbstone Press, 2007) explores the unfolding of intertwined lives and the nature of delusion. Pines has published ten books of poetry: Onion, Hotel Madden Poems, Pines Songs, Breath, Adrift on Blinding Light, Taxidancing, Last Call at the Tin Palace, Reflections in a Smoking Mirror, Divine Madness and New Orleans Variations & Paris Ouroboros. The last collection recently won the Adirondack Center for Writing Award as the best book of poetry in 2013. His eleventh collection, Fishing On The Pole Star, will soon be out from Dos Madres. Poems set by composer Daniel Asia appear on the Summit label. He is the editor of the Juan Gelman’s selected poems translated by Hardie St. Martin, Dark Times/ Filled with Light (Open Letters Press, 2012). Pines lives with his wife, Carol, in Glens Falls, NY, where he practices as a psychotherapist and hosts the Lake George Jazz Weekend.

![FLUDD Utriusque cosmi maioris scilicet et minoris [_] historia, tomus II (1619), tractatus I, sectio I, liber X, De triplici animae in corpore visione.](https://numerocinqmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/FLUDD-Utriusque-cosmi-maioris-scilicet-et-minoris-_-historia-tomus-II-1619-tractatus-I-sectio-I-liber-X-De-triplici-animae-in-corpore-visione.-705x1024.png)