Mavis Gallant & Karen Mulhallen

Mavis Gallant & Karen Mulhallen

/

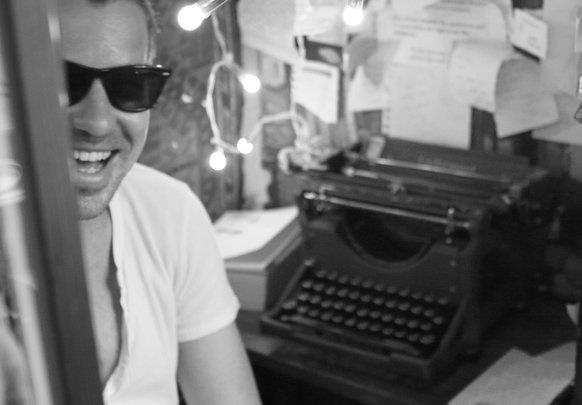

Three months after my conversation with Richard Landon, Director of the Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library at the University of Toronto, Mavis Gallant and I were able to meet at the radio station to discuss her work in anticipation of my broadcasts on her writing. We spent an entire day in the recording studio and saw one another two more times that week, off record so to speak. I found her both candid and open.

And our subsequent talks, after the tape machine was turned off and we had changed context, bore out my sense of her deep intelligence and her compassion. In rereading her stories to prepare these pages for Numéro Cinq, I found another quality, which perhaps I had been too young, or too anxious to take in — her comic, even madcap, sense of human folly.

In “The Four Seasons,” the first story in From the Fifteenth District, there is a six-page scene where a substitute priest in the British colony in the south of France is being lessoned in manners and morals, and the classics and the Bible, and of course, really, on their expectations, by his new parishioners. They have informed him there is no need to change the signage which advertises “Evensong Every Day at Noon.” They warn him about his sermons: “I hope you are not a scholar, Padre. Your predecessor was, and his sermons were a great bore.” And finally, on telling him it is time for him to leave, his host says, “Well, I’ll expect you’ll not forget your first visit.” “I am not likely to,” says the young man.

Mavis Gallant and I began to talk in the CJRT art deco studio on Victoria Street in Toronto in the morning of Wednesday, October 11, 1989. It was just past Canadian Thanksgiving, a festival which carries very specific culinary rituals, as will become later important in my brief epilogue to this narrative. The small art deco building on Victoria Street was one of a group of exquisite art deco structures in downtown Toronto, which have since been torn down. The signature building, which still stands, is just up the street at the corner of College and Yonge, the former Eaton’s College Street. Another exquisite building is at the south west corner of Gerard and Yonge, formerly a bank, now a pub. It’s impossible to think about Gallant without thinking about cityscapes, since she is so much the writer of urban life, and she chose to live the greater part of her life in a city, Paris, which has not pulled down its signature architectural structures willy-nilly.

— Karen Mulhallen

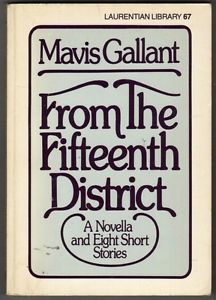

As it had been with with Richard Landon, the focus of our conversation was initially her collection From The Fifteenth District (1979), nine tales set in Europe after the Second World War. We began with” The Moslem Wife,” and Gallant read part of the story, explaining its context as she read:

Mavis Gallant (MG): The story is set in the south of France before the war and this couple, Netta and Jack Asher, owns a hotel. Just as the war breaks out Jack gets to America, but Netta is left behind, and she tries to look after the hotel, and she also has his mother to look after, and a lot of different things. She starts to write him a letter, which she never sends, but she keeps trying over and over, because what she has experienced is so remote from anything he’s been living. So she starts to write — the letter she’s been writing in her head for many years. She is in her father’s business room, wearing a shawl because there is no way of heating any part of the hotel now, and she tries to get on with the letter she’d been writing in her head on and off for many years:

“In June 1940 we were evacuated” she started for the tenth or eleventh time, “I was back by October. Italians had taken over the hotel.”

MG interjects: You must understand, that the Italian army had occupied that part of the South of France, then in 1943 the Germans occupied it.

“Italians had taken over the hotel… When the Italians were here we had rice and oil. Your mother, who was crazy, used to put out grains to feed the mice. When the Germans came, we had to live under Vichy law, which meant each region lived on what it could produce, as ours produces nothing we got quite thin…. This true story sounded so implausible that she decided never to send it. She wrote a sensible letter asking for sugar and rice and for new books; nothing must be older than 1940.”

MG: That’s all true you know, that’s all based on truth, the Red Cross people who took a German skull away as a souvenir and the Italians who were there when the Germans took over because the Italians had suddenly switched sides in 1943 and then they were put in the hotel and just left there. And the local people took them water, something to drink, because they hadn’t been all that bad, they hadn’t been anything as bad as the Germans who came in.

Karen Mulhallen (KM): Netta feels the same way, doesn’t she?

MG: The hostages who were taken for shooting at the Germans as they were retreating were all young boys and they were all taken and shot along the wall of a café and left there. There were all these true stories.

KM: Where did you get them?

MG: Well, I lived there on the border.

KM: When it was happening?

MG: Well, no, not when it was happening, but shortly after, and I knew lots of people and they told me all sorts of stories.

KM: Do you keep notebooks of people’s stories and go back to them?

MG: No, I keep a journal and anything you write down you’re apt to remember, and anything you’re told more than once you remember. One time you might forget, but when people tell you the same things over and over, they stick.

KM: Were you in Europe when all these things were happening and were still vivid for people?

MG: No, I was in the post-war period, but the whole coast was still bombed and the Germans were in the hills behind and they were shooting at each other, and the town was pretty well shot up. They didn’t begin to build again until late fifties.

I went to Europe in 1950, five years after the end of the war, so it was still the post-war period.

KM: Is that the time in which you first began to write full time, in which you decided that would be your career?

MG: No, I decided that before I left Canada, and so I went away in order to do it.

KM; So there was a kind of coalescence of history and your own decision. Do you think that might be one of the reasons why history is so essential to your stories, not just the fifties?

MG: I can’t judge whether it is or not; the reader has to judge. Certainly a book like From The Fifteenth District is entirely European history, but I wasn’t conscious that I was doing it until I started to put the book together. Then I was able to put in chronological order stories, or a story that begins with the war.

An incident in the stories that was true takes place in “The Four Seasons.” It is the story of a little Italian girl named Carmela who works for a British family. They run away because they have to go home and they say to her we’ll pay you when we come back, after the war. My story doesn’t go on from then, but after the war they paid her in devalued money. It was disgraceful. I used to look at them in the market and I used to think you’re not going to get away with that. I’m going to write about you.

KM: Did you use their names?

MG: Oh, no, there’s never anything recognizable.

KM: So it’s the bare bones of the story?

MG: It’s not exactly as it is in the story — she was a bit older than my character, and the geography isn’t exact. That’s one of the rare stories though that is lifted from an instant, where somebody said this and I thought I’m going to write about this. That’s rare. Most of the time it’s imaginary.

KM: And was that in a way to avenge her?

MG: Well, I remember when she pointed them out to me in the market — she said those are the people — I thought they shouldn’t get away with this.

KM: How did you know her; was she still living in the town?

MG: She was working for me, for everyone.

KM: In the story she goes back to her mother, doesn’t she? and is afraid she will be beaten.

MG: Well, her mother did beat her, because she came back with no money, and her mother didn’t believe the story. That part’s true.

KM: What about the ice cream? She eats ice cream and eats her way into heaven?

MG: I guess that part is invented.

KM: It made me want to go out and immediately eat ice cream.

MG: She was someone who was a good gardener. She did all sorts of things like that and worked by the hour for people. She died there. That was her life.

KM: When you organized From the Fifteenth District, there were stories that you had written over a long period, six or eight years?

MG; Yes, they were stories from the seventies.

KM: Did you decide on the order of the book, since the stories wouldn’t have been written with an eye to the collection?

MG: Yes, I put them in that order. Where the book was best received was in Germany. I’d like to know why. You would think with all the German parts they would be very touchy, but they were enthusiastic. So that was very interesting and now they are going to translate The Peignitz Junction.

KM: They want to examine their own history?

MG: Yes, but from a Canadian? That’s what is so interesting.

KM: There has already been a wave of young German filmmakers scrutinizing their history, and it hasn’t stopped, has it?

MG: No, it hasn’t stopped. I don’t mean reviews but translations. Germany figures in all my war stories, for example “The Latehomecomer,” and they have been enthusiastic about my view of Germany, and have said it should have been published in German. I am barely German-speaking, I speak like a child of five or six, but it has been astonishing for me. If this sounds like boasting, don’t use it, because I don’t mean it that way. But they said, at last a European writer, and that was astonishing.

KM: I’m trying to think of the German name for latehomecomer — Spätheimkommer? So you have given the feeling of German with the name of the story.

MG: I just translated the word into English, but what it means now mostly is people who are disappeared into Russia. Originally my book was called The Latehomecomer, but I couldn’t use that because readers would think it was about a German who disappeared into Siberia or something. From the Fifteenth District is a title that doesn’t translate into German, so it was what was chosen.

KM: But by choosing that title, changing the title, they’ve also given the book a different emphasis, haven’t they?

MG: Well, in France it was called The Four Seasons. You can’t translate From The Fifteenth District, just doesn’t make any sense.

KM: Where is the fifteenth district? I thought I should try and find it on a map of Paris.

MG: It’s imaginary, but there are small things that are not, yet it is completely imaginary. At one time I thought I would like to write some stories set in the fifteenth arrondisement. It’s the largest, in a sense the newest in Paris. It’s so new that it has no cemetery. It’s where people go to live when they can’t find a flat, so it’s the most mixed area, it has no class, it’s neither upper nor lower nor middle. So everybody who can’t find a flat will find one there. It has no character. Somebody told me it had no cemetery and that gave me the idea of the living haunting the dead.

It’s something completely new with no settled character. I was really thinking of it as a metaphor for Europe, for Modern Europe. I also got the idea of the living haunting the dead from the wife of a poet. I don’t know why widows of poets always say, he couldn’t write a word without me, you know, or he couldn’t paint unless I was in the room, or he couldn’t…whatever. I thought, I wonder what they feel like in heaven, these poets and writers and so forth. Can they hear this? And there’s not a word of truth in it: he couldn’t paint, I had to be there to look at everything he was doing otherwise he was miserable. I thought what if they go and complain, the dead, and say look at you. Shut these people up, there’s not a word of truth in it. That’s what it grew out of.

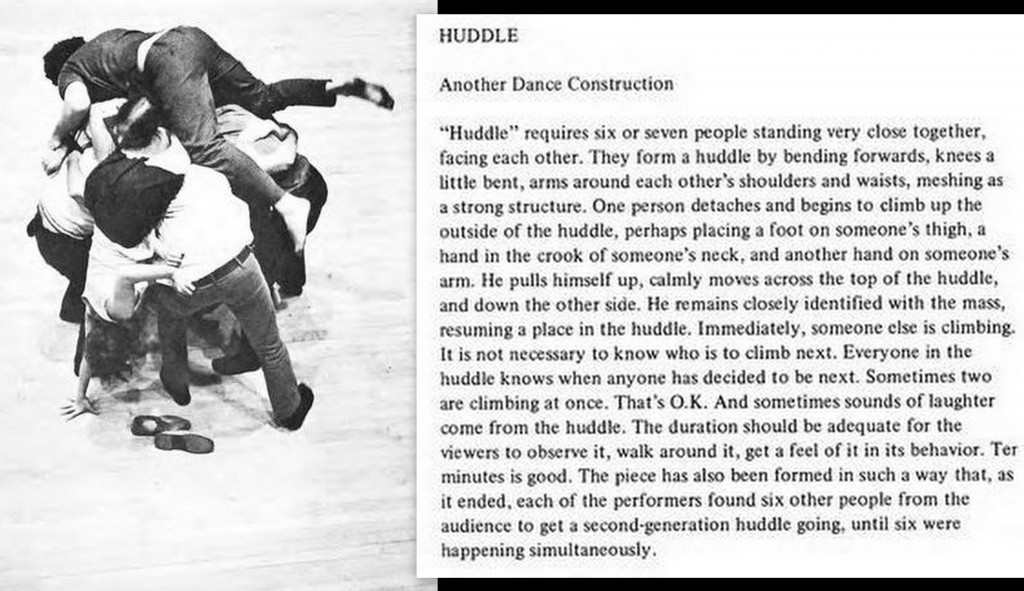

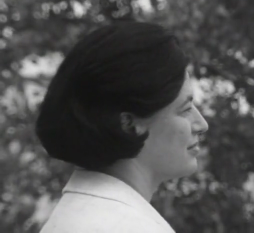

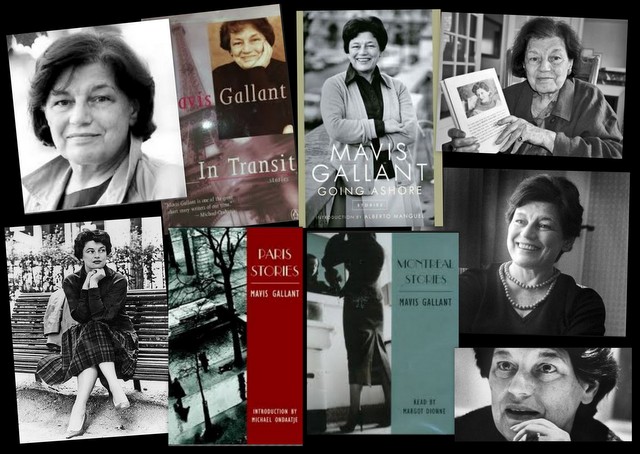

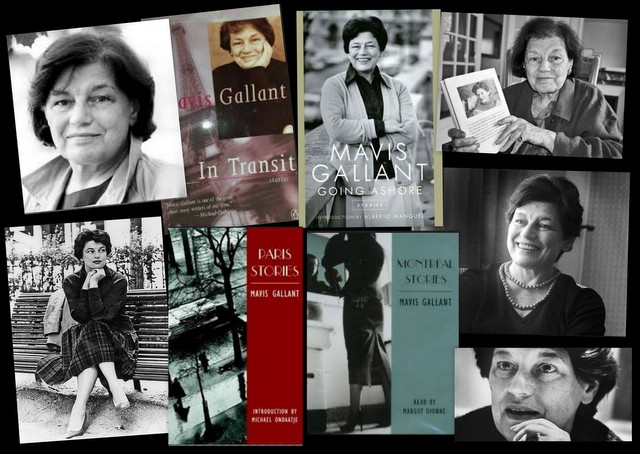

Mavis Gallant. Photograph: Jane Brown, The Guardian

Mavis Gallant. Photograph: Jane Brown, The Guardian

KM: And Irina, in the last story “ Irina,” is she such a widow?

MG: Well, no. She doesn’t say he couldn’t write without me, on the contrary.

KM: But she does say she couldn’t leave him, when Mr Aiken wants to know why she didn’t?

MG: Well, it’s probably true, and she had five children. It’s not all that simple.

KM: And there’s the scene where her husband cried because she doesn’t butter his toast properly. And of course her lover cried because she doesn’t leave her husband. There are a lot of men crying over her.

Let’s talk about Irina. It’s the last story in the collection. She seems to me to be an immensely sympathetic character. One feels a great love for her. Her appearance in the doorway with her blue eyes and her short white hair, holding her dressing gown gripped at the collar. The way she looks at her young grandson at the end and she seems to understand young people, how they feel.

MG: Yes, people who understand young people usually are not sentimental about them at all. I’ve noticed that people who are sentimental about children don’t understand them, they’re trying to make the children enter into a fantasy life of their own. She is a woman who is not sentimental.

KM: Is she based on anyone at all or a mixture? She gives that remarkable speech about women of her generation, how they’re really packages. It’s an amazing set of observations about women being packages and owning nothing.

MG: She is a mixture of characteristics. Those observations are mine. Those are things I’ve noticed. I remember asking someone in France “Why didn’t you leave?” and she said “Well, I’ve no money.” And I said, “You had a dowry,” and she said, “Well, he has it now.” So these women were often stuck because they couldn’t earn their living.

KM: So as you said a moment ago, it’s not that simple.

MG: But there are European women who have gone out and taken any job, the way a Canadian woman would. A Canadian woman might say I’d rather scrub floors than that, and she meant it. But it’s inconceivable even now in Europe.

KM: Is it just a different sense of who you are?

MG: It’s inconceivable. I gave an introduction to some friends to a Canadian architect. They came back and were very shocked because his son had a paper route.

They couldn’t understand how the son of an architect in Montreal had a paper route. I explained, well he wants a boat and his father says he’ll have to pay for most of it himself. That seemed to be very ordinary. And then they said, but you said he is an architect and his son sells papers on the street, like a common…You know it was inconceivable to them.

KM: Mavis, that allows me to ask you my next question, which is about the very real differences among the different nationalities in your stories. With “The Latehomecomer” you have a sense of a working class German family.

MG: When I began to be interested in writing fiction out of Germany, I was only interested in the working class and lower middle class. Intellectuals cannot tell you anything at all in my view in any country. I’m not being anti-intellectual and stupid, but they don’t know anything. I’d rather anytime have lunch with a working journalist to find out things, but even there there’s a limitation, they’re busy, and they see a bit too much.

I didn’t think the working class was a victim of what happened in Germany, they were a part of it, of the movement, not out of evil-mindedness, but out of a deep depression. I don’t mean that the industrialists didn’t put money into the Hitlerian movement, but I don’t think that having lunch with an industrialist would have got me anywhere, whereas meeting these people on a friendly basis, I did find things out. The only thing that interested me was finding out from them, because a victim can only tell you what happened to him.

You know you have to know what was going on in the mind of a man in the firing squad. I don’t pretend I ever did find out, but I got enough to satisfy my interest a bit.

KM: I think what you are saying is that the different classes have a completely different value system?

MG: They do anywhere.

KM: In North America the architect’s son can sell papers on the street?

MG: But that doesn’t mean that he is going to marry a working class girl. Necessarily a different thing. Unless she’s been to the same university as he has, or something like that. It’s more fluid in North America but it’s pretty snobby too.

KM: Yes, the class system is still here; do you think it is easier to see it in Europe?

MG: It exists everywhere, probably in societies I know nothing about. When I first went to Europe in 1950, the class structure was distinct. I couldn’t stand England for that reason. In fact I loathed it. I couldn’t bear to stay there because it was so contrary to everything I admired or believed.

KM: In your stories, characters who are expatriates are in a sense out of class, aren’t they?

MG: Except among other expatriates.

KM: So then the class system kind of kicks in again.

MG: There was a British colony in the south of France, and it was like ancient Egypt, you know, with a pharaoh, and there was always something very amusing about it.

KM: What about Eric Wilkinson in “The Remission?” He’s able to adapt to different accents.

MG: He floats up and down and we don’t really know very much about him except that he can act a bit. The view of the others in the British colony pretty well fluctuates with his fortunes.

KM: And the kind of curry he can cook for dinner! They pay him five pounds, don’t they? They offer him a fiver.

MG: It’s been a long time you know…

KM: Now Gabrielle Baum is also an actor.

MG: That’s my favourite story in the collection: “Baum, Gabrielle, 1935—( ).”

KM: It’s a lovely story.

MG: It’s really about Montparnasse more than anything else and the changes and it’s through the sixties.

KM: Yes, I was going to ask you if it wasn’t about the whole feeling of the changing district. La Méduse — is that the name of the bar, and the old car seats, and so on?

MG: In the sixties and the seventies all those English style pubs came in and orange lights. There were scenes for recruiting for the Resistance TV and film productions. A series of five episodes or so. I actually used to go to one or two cafes there and someone did come in and say in a very practical way, “I want 12 Polish Jews for deportation.” And everybody was saying me. Me, me, me. I couldn’t do that. And then somebody would say: “Don’t take him. He doesn’t look Jewish.” They usually picked Yugoslavs for nearly everything, but I’ve forgotten why. They were great drifters. There were actors who did these bit roles and they would try and get a speaking part because they’d get more money. And that was why there were so many of these long deep silences in French films. They just didn’t have to pay them much if they didn’t say anything!

KM: Now that story ends with something about age. Gabrielle says his father lived to ninety. How does he feel about that?

MG: I think he thinks he has lots of time. He’s an actor and he works all the time. He’s not a drifter. He always lives in the same place, he won first prize at the Conservatory and so forth. But you know there are an awful lot of actors who are unemployed. There is 90% unemployment. And he does have that mystery in his life, of what became of his parents. They just disappeared, probably picked up by the police. I don’t say I know because I am seeing from his point of view, so I can’t pretend to know more than he does. But I think anyone reading it would guess that his parents have probably been picked up in the street one day.

KM: They were in the south of France weren’t they?

MG: There was a point where it was a free zone, and then the Germans occupied the whole thing, I think that was in 1942, so everyone was at risk. People were picked up in the street.

KM: And then some people had left early enough to get to South America. Is that what happened with the uncle, that he had gotten out earlier? And he seems to despise Gabriel’s parents for not having gotten out earlier.

MG: Yes, he seems to have gotten out before the war and feels they dithered.

KM: Why is that your favourite story?

MG: Because of Montparnasse and the kind of people in it. When it was translated I reread everything and I recognized the Montparnasse of the sixties and the seventies. I think I had it right.

KM: Have you noticed Paris changing in the years you have lived there and how do you feel about any changes?

MG: Oh yes, it has changed and I regret the decline of Montparnasse. But those things have to happen. There are still cafes.

KM: That’s one of the things Gabriel talks to Dieter about, isn’t it, the changes?

MG: It’s nothing to the changes now in the architecture. When it comes to hideous architecture, the French are the champions.

KM: Some people, for example Prince Charles, would say the English are the champions.

MG: Paris has not been destroyed anything like London. Prince Charles has superimposed a painting of London as it was, I think it was a 17th century painting, over the skyline today, but you could put an old painting of Paris over today’s Paris and still find a lot of it. And there are some new buildings which are beautiful, like the Arab Institute. And the Pyramid in the Louvre. They’re beautiful.

Mavis Gallant

Mavis Gallant

KM: Let’s go back to “The Latehomecomer,” which is written in the first person. I think that’s a surprise to have the narration in the first person after reading several stories in the third person. Generally in the stories there is the feeling of knowing everything the narrator seems to know. That’s an exhilarating thing about your writing.

MG: Well, I just wanted to tell it that way, more intimately, from his point of view throughout. But his mother is from her point of view. In the letter she says, “I was your mother.” That’s much stronger in English than in French. In French it doesn’t mean anything.

KM: In English, it’s like a sudden bolt.

MG: And I’m not a writer in the French language and I don’t do my own translations. If I wrote first in French I might know a way of doing it, but I don’t. The humour doesn’t come through in translation either, at least not much.

KM: When you write a story, do you work from the characters? How do the stories come to you?

MG: As images of the people. “The Remission” was the first of them. I remember this because I kept my notes, which usually I tear up. I saw the family getting down from the train, there’s nothing like that in the story, but that was the first image. I saw them getting down from a train arriving in the south of France with three children, the mother and the father and the 1950s clothes and suitcases. I had a sort of image and I built from that.

KM: And then did you begin to imagine what their lives were?

MG: You don’t imagine anything; it just comes to you. For a few days after that things come out of the air, you write them down, and then it stops, that onrush of several days, and then you have to work from there.

KM: Is there any time in which you know a story will be with you, a specific period in which you work, a special time of the day?

MG: In general, I work everyday. If I have an idea for something new, you don’t control the time, it just rushes in. On the whole, I get up and I work, that’s what I do, I write and even if it’s going badly I just sit there. I usually eat lunch around 2 p.m.

When it’s going well, it’s perfect, and when it’s not, it’s an awfully long time.

KM: Do you stay with a story until you feel it’s done, or do you write several at once?

MG: I work on several things and come back and then when it’s done, it’s done. When I am getting to the end of a story, I don’t do anything else at all.

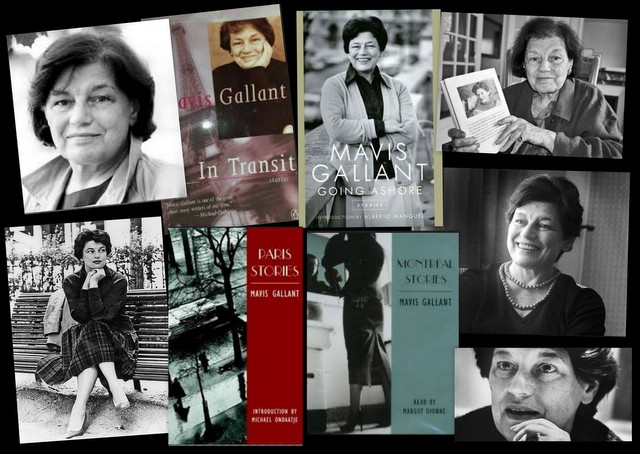

KM: You’re immensely prolific; I ‘m sure other people have said this to you. There are hundreds of stories.

MG: Isn’t it funny, I think I’m not prolific. There are over a hundred stories, but not hundreds.

KM: In 1978, there were a hundred, and there are so many uncollected. You have twelve books.

MG: There are still some which are uncollected, from 1985 on. But I want to publish a novel before I publish another collection, and I’m working on one now.

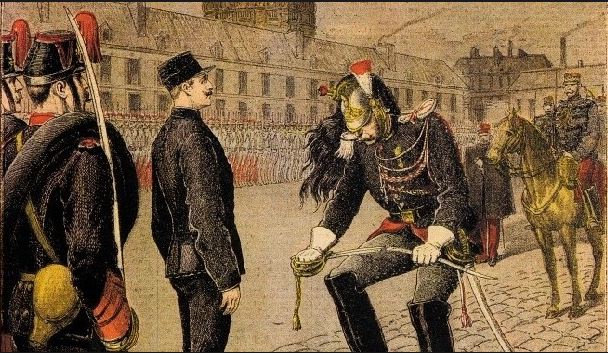

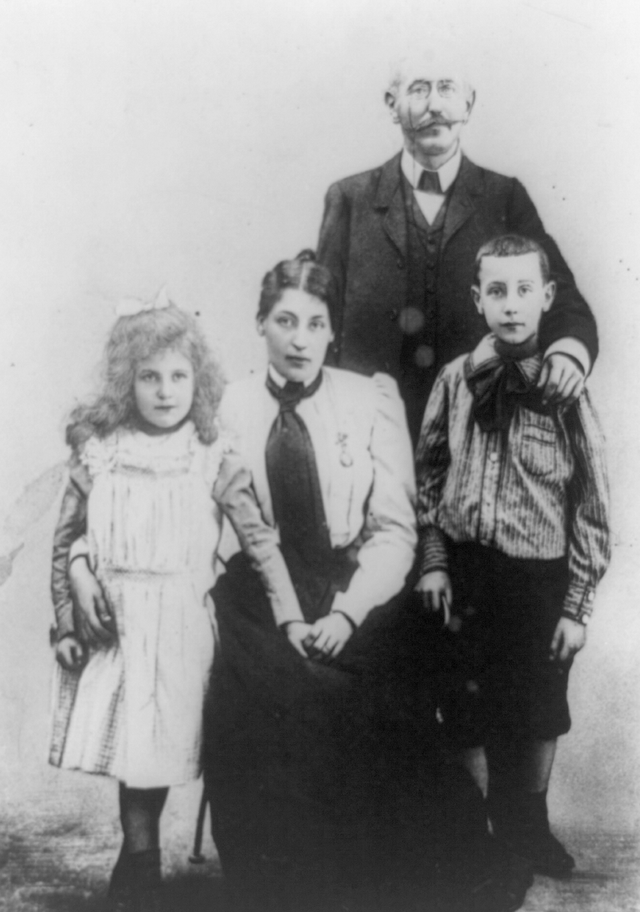

Alfred Dreyfus

Alfred Dreyfus

KM: Tell me about your Dreyfus book?

MG: How much do you want to know? First, it wasn’t my idea, but it was the American publisher, Random House, who asked me if I wanted to write about the Dreyfus case. I accepted without realizing. I’m not an historian, it’s not my training, my training is journalism. I was a journalist all through my twenties, and that’s how I look at the world a bit. I accepted because I thought, well, probably no woman has ever done anything like this. Although I knew about the case, I didn’t know what I know now. I knew Alfred Dreyfus had been unjustly convicted of treason and I knew he’d been sent to Devil’s Island. I didn’t know for how long. I knew that the French writer Émile Zola had written passionately about this in a newspaper article which had the famous heading “J’accuse,” I accuse. I knew he had had a famous lawyer named Fernand Labori. I knew that he’d come back and more or less disappeared. But it ended there. I knew nothing more about him.

I looked it up in a French encyclopaedia to get a beginning, and I saw it was a huge fresco of French society. I became wildly enthusiastic about it and I said I could do it I thought in two and a half years. Famous last words. Two and a half years later I was still looking, looking things up, meeting people and carrying on

It was an extraordinary experience for me to do the research, which is done. In fact if someone came along with some startling thing, I don’t even want to hear it. I’ve done my research, its miles and miles of notes and stories and interviews. I got in at the right time, because Dreyfus’s daughter was still alive. I couldn’t work from documents, because I didn’t want to write the books I was reading. They told me about the case, but they didn’t interest me. I wanted to know about the people.

I used journalistic techniques. I took my telephone and my notebook and I called every single person I knew in France who was French. Everyone. I mean people I had not talked to for years. I asked do you have anyone in your family who had a connection to the Dreyfus case? And then I began to be more general, have you any Jews in your ancestors and don’t say no right away but ask your grandmother. I got people who had been Jews at that time. People who had descendants whom I knew and who often didn’t know their own life history. Do you have anyone in your family who were officers at that time? Don’t say no, ask your grandfather.

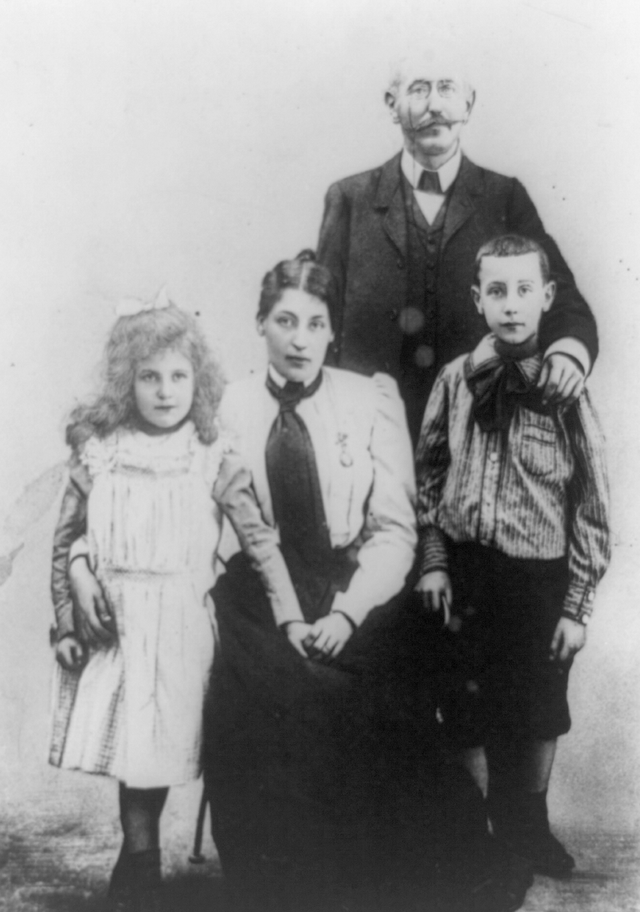

Dreyfus with his family, 1905. via Wikipedia

Dreyfus with his family, 1905. via Wikipedia

In about three weeks, I had Dreyfus’s daughter, and I knew all about Esterhazy’s daughters — he’s the villain of the piece; he’s the one who was the German informer, not poor Alfred Dreyfus. I had the daughter of the man who’d been chief-of-staff in the army and who worked against Dreyfus. I had that generation of elderly people, all defending their fathers, whichever side their fathers were on. Those loyal daughters, and believe me this is something — no matter what side their father was on, he was right.

The great help to me was Dreyfus’s daughter Madame Jeanne Levi. I didn’t get to her right away. I’d asked a book seller I knew whether anyone among her customers or clients might be connected to the case. She called me and said I have a customer who is a great niece or something by marriage. I only met two people who knew my work or anything about me, so I went in as a complete stranger. She read English and read The New Yorker, so she knew a bit about me. That was a great help. The others didn’t know any English, and so I just came on as a foreigner really. This woman was the first. She looked me over. Then she invited me to lunch to look me over. Then she invited two of Dreyfus’s grandsons, who were both doctors, and their wives to dinner, to look me over. Then one of the grandsons, one of the doctors turned to his cousin, it was rather dramatic, and he said, “You may make an appointment with my mother to meet Madame Gallant.” This man’s wife took me aside and said you are not going to get anything out of that family— they have a policy of total silence. I said, well then, I will have to work without them, but if I can talk to them, that would be even better.

So then I was taken to tea with Dreyfus’s daughter, who was a stunning elderly woman. She was in her seventies, with white hair and she looked like an English woman to me. I can’t explain why I would have taken her for an Englishwoman of a certain class. She had blue eyes, lovely white hair and she was very, very straight and rather solid and very careful. She didn’t know much about me and we talked about general things. She showed me a few innocuous souvenirs and at the end of the tea she said, “Je suis à votre disposition.” I am at your disposal. Wow. So I waited more than two months, as I didn’t wish to push her and then I called.

I came and I brought her a box of chocolates. It was Monday and the florists were closed, or maybe there was some other reason why I didn’t bring flowers. I said to myself elderly people like sweets. She was delighted and said that her mother never let them have candy because they were afraid it would be poisoned. Anti-Dreyfus. People sent boxes of chocolates for the children, but she always threw them out. So they were brought up very, very strictly, and in her old age chocolates were a treat. She could have gone out and bought herself chocolates, but they were brought up in such a way that they wouldn’t, would ever self-indulge. It was quite an experience for me, and here I am old self -indulgence herself in contact with this rather rigid view. In the end, I had her going to restaurants with me, and eating desserts and carrying on. I loved her dearly. She died ( 1893-1981). She helped me a lot, a lot!

Dreyfus and his daughter Jeanne, 1910. via Clioweb

Dreyfus and his daughter Jeanne, 1910. via Clioweb

KM: When will the book be done?

MG: A fortune -teller in Bangkok told me it was the last thing I’d ever do. That doesn’t encourage me much. I can’t tell you when. I think that would be tempting fate. It’ll be done certainly. I’m not going to spend half my life on something I’m not going to finish, didn’t finish.

KM: How long have you been working on it?

MG: Many years.

KM: I won’t ask you anymore!

MG: But I have learned a lot and I haven’t any startling conclusions. I do have things that I think are interesting about what people were like who populated the story. Dreyfus is an enigma because everyone is so contradictory about him. But I think I’ve a clue as to what he was like. It’s a clue: he’s a man who’s very nervous. Tension. He always speaks of “my damned nerves” in his letters. “If only I could control my damned nerves.” But he’s all of a piece, he doesn’t flounder all over the place. He was a pathetic figure in a way, yet it was the last thing he wanted to be.

KM: But you must be very interested in this story even if it is a book you were asked to write?

MG: I could have wound it up a long time ago, but it would have been the book I did not wish to write. I am not going to turn in a book that I do not wish to read. It’s a very difficult thing I have done. The first third is an essay setting the case in its time, and explaining. Alfred Dreyfus was an Alsatian Jew and he was also an officer. What is an Alsatian Jew; what is a Jew in France; what is an officer? I begin with the officer, because— you won’t believe me— it was the most important. Nobody can understand the Dreyfus case who doesn’t know what it meant to be an officer in the French Army at the end of the nineteenth century. It explains his behavior, it explains the way in which he almost went along with the thing out of loyalty to the army. Things that are inconceivable to us today. As for the religious side of his life, I can only trace it through letters, his letters. There’s a point where he says at the beginning: “I trust in God. God will get me out of this; it’s the God of mercy and so forth.” And then one day he writes, “God has abandoned me.” Whew. Finished. There’s no more mention at all. Someone who is all of one piece lost his faith, it’s obvious. That’s interesting to me, but it’s not interesting to anybody else. I mentioned it to people, and they say well who cares? Well I do, because you can’t judge a man, or a woman. But we’re talking now about a man: every attitude has to come into it. The attitude to religion, the attitude to money, the attitude to his wife, the attitude to women, to his country, to history. I’ve read books that said he was a snobbish officer. He wasn’t snobbish at all. He was an officer. He had it in the blood. Some men are like that. I’m not like that; I’m a pacifist. So it was even more interesting for this pacifist to encounter a military man. That was fascinating to me. And people’s memories of him varied. His daughter adored him; he was so kind to her. Other people found him stiff, cold, sometimes inexplicably cold. But it was a horror of sentimentality, and a horror of people gushing, and a horror of people crying all over him— he would just freeze.

I interviewed two women, witnesses, one was a hundred years old, the other was 99. The one who was a hundred remembered being at one of the first gatherings — we would call it a party — when he came back from Devil’s Island. Everyone applauded when he came in, which embarrassed him, and then a woman rushed up to him and flung herself into his arms, well not his arms because he kept them at his sides, and said: “Oh Captain Dreyfus, the dream of my life has been to meet you. Now I am meeting you, you’re my hero, and you’re my this and that.” And he didn’t answer. And she became hysterical because she thought he had turned to stone or he was dead, or something had happened. And she went on and on and he didn’t answer.

And she had to be led away in hysterics. He just stood there; he was incapable of saying that’s enough, or calm down or anything like that. He was all of a piece. He just didn’t answer. People remember him and his family with his watch in his hand.

Dinner was at 7:30 p.m. and not a minute before and not a minute after.

He was a military man, and a loving father, and a loving husband. I think all these things have to be put together.

Mavis Gallant in The New Yorker

Mavis Gallant in The New Yorker

KM: Mavis, are there writers who have been important to you?

MG: The writers that are important are those you begin to read as a child. I’m convinced of that, quite serious about it. The wealth of books in the English language for children was extraordinary, well-written, with style. Like Lewis Carroll. I regret that children read less and that they are not read to and that they are taught to read so late and so badly I think the Swiss psychologist Piaget is going to have to answer for a lot in heaven. There must be a wicket they go through in heaven for what they had to do with a child’s education. And they are going to say: “Are you the man who started them reading at seven? Purgatory for you!”

KM: Piaget and B.F. Skinner together? I wanted to ask you about Tolstoy?

MG: Oh that goes on and on, but the basic English style comes from the first books you read. Then you begin to read more and more widely. I read the Garnett translations of Russian writers rather young, but I don’t mean at twelve, but older. I read an awful lot of that, and Chekhov was probably very important, although at the time you don’t know that. You just read them.

KM: Because you have been talking about the war, and about a man, his society, his religion, his profession, I was thinking this is the way — I am sure people have said this to you before — this is the way Chekhov thinks, this is the way Tolstoy thinks. You do see a human being in a total social, political religious context. Not all writers do.

MG: If I started to think that I was anywhere close to these people I would think I was paranoid, and I would go instantly to a psychiatrist and ask him to bring me down to earth. So, no, I have always thought it is my journalist’s training.

KM: To see the total context?

MG: Yes.

KM: The reason I’d asked you earlier about how you write is because it seemed to me that when I pick up a story by you and I look at a single sentence, the sentence seems to include the world, there is a total context all the time.

MG: I don’t like reading things that aren’t set somewhere. I don’t like never never land.

KM: Do you travel to all the places you describe, for instance Berlin, Budapest? Are these places you have visited?

MG: You are living in Western Europe, and so earlier yes. In the last few years I‘ve been coming more to Canada and to North America.

KM: You’ve written many stories set in Canada.

MG: If I stay here a while, I go back and I just bubble up. I lived here in ’81, ‘83, ’84. I had a very good time. Do you think the city has changed since then?

KM: Yes it has.

MG : In what way?

KM: There’s tremendous destruction of the city itself and there are many more homeless people. And the class distinctions are much sharper.

MG: I haven’t been where the homeless are, because I’ve been around the university.

KM: You’re in the ‘shopping danger zone’.

MG: And I go wherever I’m going in a taxi.

KM: Your Paris Notebooks were recently published and in them you discuss 1968. Could you say a little about that moment in French history, which you experienced directly and which speaks so tellingly to your intense scrutiny of French society?

MG: There’s a passage in the book which comes directly from my journal. On the twentieth of May, 1968, I saw people hoarding. The reaction of the people of Paris went straight back to the war. Whenever there is a crisis in France, you can tell it’s a real crisis because sugar disappears from the supermarkets. It’s striking. You go to the supermarkets, and all you get are the grains of sugar on the floor. People were frightened that if there was a civil war, food would be missing. I’d never seen that kind of public reaction.

Later in the diary I mention a shop owner who, when the wind turns, puts up only right wing magazines. And I remind him of what he’d been thinking about two weeks before and he said, “I don’t know what you’re talking about.”

KM: Mavis, you live in Paris, and you write in English in a French environment. How do you keep your English intact?

MG: Well, it was never a problem until a year or two ago. I don’t speak enough English. Most of my friends are French-speaking. If they are foreigners, we speak French together, because it’s what we have in common. Of the Canadians whom I see and talk to, there’s Joe Plaskett, a Vancouver painter. But there aren’t many Canadians because they don’t form colonies, they’re all very independent, each going off by himself and so forth. But I never had trouble maintaining English until my work was translated into French, about two years ago. Last year the first books were published, and the year before I was reading the proofs of my own work in another language, helping with the translation, my own ideas expressed not as I expressed them. Then I had a lot of trouble with English, I began to think in French syntax. I wasn’t thinking in French, I was thinking in English with French syntax, which is completely different. I had to take strong measures, and I mean strong, otherwise I would have had to leave the country altogether.

KM: What did you do?

MG: Well, these might sound odd, but I don’t read or speak any French at all until I’ve finished working for the day. I read only an English newspaper, I listen to the BBC news. At 7:45 every morning CBS American News with Dan Rather. It’s with French subtitles but it’s in English. I watch a bit of it, not the whole thing. It’s also the only place where I can get any Canadian news. I read only in English. I have to get on the English track in the morning, listening, reading. I’m probably alright now, but I’ve gotten into this habit of a year and a half. I don’t answer the phone in the morning. From lunch on, it doesn’t matter.

KM: Do you dream in English?

MG: Both, but I had to do that. I thought it was the most drastic thing to do, but it helped.

KM: Created a kind of barricade?

MG: It’s like two tracks. I had never before confused them. I had never used an Anglicism in French, put English words into French, used English syntax in French. If I do that in English, it’s a bit of a joke. Sometimes you are joking and you use some French words in English. You know we say hors d’oeuvres or détente, and it’s not really thought of as French. It was a question of the syntax, which is completely different. I don’t think it would have lasted, and I do think it just came from reading those proofs. I read French all the time and it has never impinged. But my own work in French had a devastating affect on me.

With the third book, I didn’t help nearly so much. I read it quickly to see if there were any real semantic mistakes, but I don’t read it for mood, tone, tense, etcetera. I thought even if it’s wrong. even if it’s a betrayal, it’s dangerous, too dangerous for me.

KM: Do you have a translator that you trust in France?

MG: I did, but when I was in Vancouver a short time ago, I met a woman at the University who is writing her MA thesis on the betrayal of my work in French. She calls it betrayal. It is a question of mood, of tense, of using verbs in a different way, and so forth. And I said to her, well, you are probably right, but I can’t do anything about it. I will correct actual mistakes, where I’ve said geranium and they think it’s nasturtium, but the rest I simply can’t cope with. I thought that would interest you?

KM: It does, and in French Canada today this is a constant question, isn’t it, about the relationship between the French language in Quebec and English.

MG: Well, I maintained mine for nearly forty years with no problem. So it certainly can be done. I never never had any problems at all.

KM: It’s also interesting that it just came at this particular phase…

MG: It’s seeing the images. When you read someone’s work, you see images. The author cannot provide what’s in his head. You provide the images. When I read my own work, I see my original images. But seeing my original images in another language was as if two railway tracks went together.

KM: Thank you very much, Mavis, for your generosity.

/

Epilogue

I saw Mavis Gallant three more times after this long day of interviewing and taping.

We went for lunch at a French bistro, then located on Queen Street West in Toronto. At that time, Le Select had bread baskets strung over each table with clothes line tackle. Luckily the main dining room was full and the waitress decided to squeeze us into a small front window area. We sat near the entrance to the alcove and settled in to talk about Toronto and her time here and Janice Keefer’s recent book on her work, when the waitress asked me to pull in my chair so some other clients could get by. After she left, Mavis commented that it was interesting that the waitress did not ask the table next to us to pull in, which would have been equally effective in freeing up passage. The next table was occupied by two men in red ties and grey business suits.

We talked as well about aging, what it means for a woman, and about Gallant’s own intention to stay full-bodied to preserve her skin, and about her love of pumpkin pie. It was a few days only after Canadian Thanksgiving and Mavis was staying in The Windsor Arms Hotel, then and now a chic hostelry in the most expensive shopping district in the city. On Saturday, I made my way to the St Lawrence Farmers’ Market and then drove up to The Windsor Arms with a fresh baked pumpkin pie for Mavis. She was delighted, of course, because there was no pumpkin pie on the menu at The Windsor Arms Hotel.

Years later, I ran into Mavis at the Writers’ Suite in the Harbour Castle Hotel during the International Authors’ Festival. I was with my friend Nancy Huston, each of them had flown in from Paris to read that week, and the suite was crowded with writers from all over the globe. Mavis was sitting on a sofa, surrounded by admirers, but she seemed delighted to see one, or perhaps two familiar faces. We began to chat, but then a well-known Canadian poet began to drunkenly declaim and to threaten to punch out another poet, so the three of us, rather wistfully I thought, said good night. I never saw her again, and the notes from her unpublished Dreyfus book, I understand, were still stuffed into a closet on her death this past February, as fiery battles shattered the Ukraine. She was a writer who belonged both to Canada and to the world. We will not see her like again.

—Mavis Gallant & Karen Mulhallen

/

Karen Mulhallen has published 16 books (and numerous articles), including anthologies, a travel-fiction memoir, poetry and criticism. She has edited more than 100 issues of Descant magazine. She is a Blake scholar, a Professor Emeritus of English at Ryerson University, and adjunct Professor at the University of Toronto.

Mavis Gallant. Photograph: Jane Brown, The Guardian

Mavis Gallant. Photograph: Jane Brown, The Guardian