Margret of Antioch

Margret of Antioch

See how slow and

sure I glide. See my organs

wings. And you, little

fish I once plunged for

–nameless invisible fish in

deepest darkest ocean.

Changing, Richard Berengarten

Breakfast at Nick’s

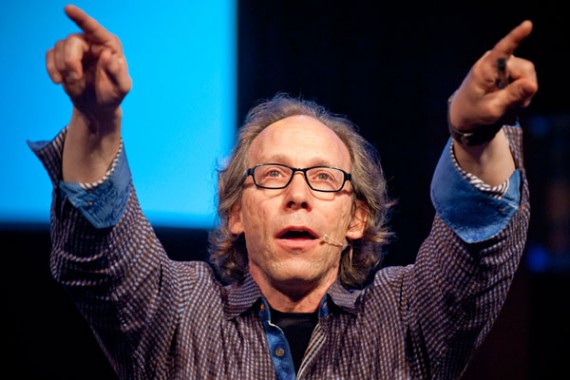

For several years after returning from Vietnam to the bewildering streets of New York’s lower East Side, I spent hours every morning at Nick’s Diner on the corner of 2nd Avenue and 4th Street recording dreams. The images that I brought back nightly from sleep, embedded in dramas that pointed to meanings I could almost but not quite understand, were irresistible and relentless. The old Greek proprietor in his lightly stained white apron and half smoked cigarette, the pale blue eyes peeking out of thick, black rimmed glasses was a guardian at the gate. At Nick’s I could sink into my dream-world and feel safe. I would later think of the place as an Asclepian incubator, where I could follow the procession of images to their destination as the smell of coffee, home-fries and bacon wafted from the grill.

Now and then, I’d find the diner closed and knew the proprietor had gone to the track. Otherwise I could depend on the white haired man leaning on the counter to nod as I entered. There were seldom more than five or six customers, mostly on the stools, perhaps one or two at a table. But not my table, a small two seater at the window with a view of Café La Mama across the street. One of the regulars at the counter, a man who made random duck noises, bothered no one. In minutes, Nick set my toasted bran muffin and mug of coffee down next to my open notebook. He did it soundlessly, then returned to his post. I ate slowly, seated next to the one piece of nature in the room, a drooping potted snake plant, and began to write what I recalled. At first I felt lucky to remember one or two dreams. Slowly, my ability to retain whole sequences of dreams increased until I was spending as much as three hours every morning at the task. More time than I’d thought possible. Once dreams were recorded, I floated through them, over them like a man in glass bottom boat above a vibrant coral reef. I never felt rushed. Nick appeared to understand that I was fishing for something important in much the same way he handicapped the Daily Racing Form. I did this for three years, until the bleachers at Aqueduct fell on Nick and the diner disappeared and almost instantly, as in a dream, became a bodega.

What started at Nick’s shaped my exploration as a poet, and later my practice as a psychotherapist. In the privacy of my office I worked with clients’ dreams, fishing for images that might yield insight into patterns and impulses that drove their lives unseen. In this respect I think of myself as part of a lineage dating back to the god Asclepius in the 4th Century BC who healed through dreams. Not surprisingly, I picture Asclepius in a white apron behind a Formica counter reading the Racing Form.

Before Socrates died of self-administered hemlock, he asked his faithful friend Phaedo to remember to bring Asclepius a cock in payment for an old debt. I can easily believe that in his search for truth, Socrates recognized this alternate dialectic with the unconscious that occurred in the Asclepian dream-chambers. And the manner of payment, a cock, represented this as a wakeup call.

Nick’s diner was my dream incubator.

Perhaps I’m taking my penchant for reading things symbolically too far, but I believe there are correspondences between Nick and Asclepius. Both Greeks died violently. Asclepius from a thunderbolt hurled by Zeus as punishment for bringing shades back from the dead. Nick, under falling bleachers while calculating the odds on the Trifecta. Socrates as we know died at his own hand in his own time, refusing the opportunity Phaedo offered him to escape the death sentence imposed on him for corrupting the youth of Athens in his pursuit of knowledge. Whatever he had uncovered in this pursuit left him unafraid to cross the threshold. And it was at this point he acknowledged his debt to Asclepius and asked Phaedo to honor it.

In this respect, I believe Nick was Socratic. I’d like to think that in the eternal instant that precedes death as the bleachers fell on him, Nick managed a smile.

I continue to search the dark reaches of sleep for images that fill me with awe and fascination, and to remain in touch with the intelligence that produces them.

“Dreams” by Douglas Leichter

“Dreams” by Douglas Leichter

Trolling these waters, I learned that my nightly dreams constituted a personal myth, but that Mythology functions as our collective dream. Both divulge meaning through symbols and archetypal imagery and serve as portals for information that enlarges waking consciousness. A key function of dream and myth, personally and collectively, is the integration of experience, without which the psyche would split, exist in what might be compared to a schizoid state, “beside itself.” As Carl Jung might have put it, The Spirit of the Times must be informed by The Spirit of the Depths.

Mythologist Joseph Campbell introduced me to Minnesinger Wolfram von Eschenbach’s 13th Century romance, Parzival. Parzival, a Holy Fool searching for the Holy Grail, arrives at the Grail Castle where the wounded Grail Keeper, Amfortas, awaits one who will heal him. Amfortas eases his pain by fishing, and so becomes known as the Fisher King. Moved blindly on his mission, Parzival is allowed a glimpse of Grail and the Castle. It is like a dream from which he wakes. In the morning, the spectacle disappears. Parzival has glimpsed the Grail’s power, but can’t understand the experience. Slowly he becomes aware that the Grail calls out to one who is worthy of it, and only that one will be able to heal Amfortas and the Waste Land that mirrors his condition. Until that time, the Fisher King daily floats his line in the water from the back of a boat to ease his pain.

The myth resonated inside of me from the start. Years after Nick’s diner had disappeared like the spectral Grail Castle, where I had glimpsed the Intelligence that composed and delivered my own dreams, I grasped the central meaning in the myth: in order to heal the wounded Fisher King Parzival must expose his own hidden wounds. Parzival’s journey through the Waste Land echoed my own.

In February 1966 at the age of twenty-six, I disembarked from the S.S. Esparta at Seattle-Tacoma after six months in Vietnam. The journey was from a war ravaged land to one torn by civil strife. I’d watched homeless orphans in Saigon sell mariposas to GIs, while counter-culture children in Haight-Ashbury got high and pinned flowers in their hair.Timothy Leary instructed his audiences to “turn on, tune in and drop out,” as Henry Kissinger advocated carpet bombing and the use of Agent Orange. Protestors chanted to end the war. Vilified soldiers brought the abyss back with them.

Saturn devoured his children.

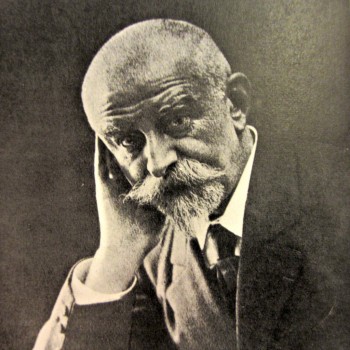

“The Despot” by Marc Shanker

“The Despot” by Marc Shanker

The cultural nightmare also laid waste to any claim to sanity by those in authority, balance and trust, all required for healing.

The Post-internet Waste Land is even more deceptive because the new technology that can spin any condition to appear to be its opposite. Hyper-stimulation and desensitization walk hand in hand. Pain hardens into confusion, or explodes in acts of terror. Disconnection looms at every intersection of the Information Super Highway. Environmental degradation proceeds in tandem with urban gentrification. The inherent contradiction in this behavior is no less telling than the one in Parzival’s world where knights left children orphaned in the name of love.

It seems to me that the Fisher King is still in pain, floating with his line in the water, waiting for one who can address the disconnection in the human heart.Parzival may be the first tale on record to identify the wound in Western culture as a failure of intimacy.

I’ve worked with countless dreams, my own and others, since Nick perished beneath the Aqueduct bleachers. At the rate of change in our culture, decades register as centuries. We are on a rocket ship, pressed by the G-force and fortified against it by all manner of desensitizing devices. But the basic structure of the human psyche has not changed since our ancestors inscribed their images swimming in the Paleolithic darkness of those great caves.I have no idea how to approach the problem on a massive scale, but as a therapist I try to do it one person at a time. But while the structure of the psyche remains the same, the environment that surrounds it has changed dramatically.Von Eschenbach mythos speaks to me through the mists of time. But it was brought to light eight centuries ago. What do the Fisher King and Parzival look like today and how are they embedded in the particulars of our lives? The messages received nightly in sleep may provide the best clue.

.

A Case History

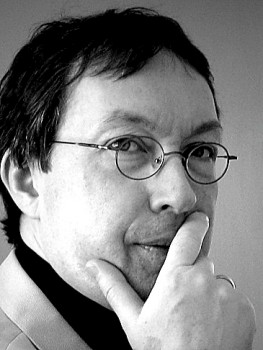

![chaim-soutine-by-Tekkamaki[68597]](https://numerocinqmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/chaim-soutine-by-Tekkamaki68597.jpg) “Chaim Soutine” by Tekkamaki

“Chaim Soutine” by Tekkamaki

Perry is Parzival, or as closely cut from that physical cloth as anyone today might imagine. At 6’2”, he has linebacker shoulders, blue eyes are set deeply under a ridge of brow that give him the look of an eagle focused on a world of prey below. The warrior aspect is softened by blond hair, and an open smile. Heads turn when he enters a room. A survey of his gifts reveals that he is a discerning collector of folk art, stalwart conservationist and outdoorsman, formidable chef and sommelier, and a canny business man. In the course of fifty years, Perry has made a living as a rock drummer, night club owner, music producer, and currently as a high-end realtor. His version of the Grail mission is contained in his ambition to be the best possible human being he can, which includes helping those he cares for in any way he can.Women are drawn to him as they might be to a knight who will save them from loneliness, disappointment, and a history of trauma.

Perry projects the fantasy lover to many of the women he meets. The question that troubles him most is his own inability to sustain intimacy. Parzival’s confusion upon leaving the Grail Castle after glimpsing the Grail, might describe what Perry feels after a glimpse, followed by the loss of intimacy. It’s the source of great pain and self-doubt. Perry doesn’t understand why the condition exists, or what to do about it.

Perry’s romantic relationships have been mostly short term, fragmented, and hit-and-run. Certain women endure his brief appearances and longer absences in their lives for months, or even years—until it becomes intolerable to one or both of them. Our sessions over five years have focused on Perry’s wounds sustained at the hands of a sadistic father, and an enabling mother. Physical and emotional violence suffuse his earliest memories. As a child, when things heated up, Perry retreated to his room where he beat out rhythms with drum sticks on a practice pad and imagined he was a rock star in silver tights.

When we first met, Perry exuded a strong bonhomie. The traumatic events of his youth appeared to have disappeared into a life rich in friendship, fine wines and gourmet meals balanced by regular workouts at the gym. Only his painful experiences in relationships stopped him from addressing the void left by a sadistic father and sacrificial mother. The most promising preludes led inevitably to feeling trapped in an intolerable domesticity that made him flee in fear. Most attempts to develop a relationship sent him fleeing out the back door in a matter of weeks.

Until he met Cassandra.

“Crowning of the Poet” by Grace Hartigan

“Crowning of the Poet” by Grace Hartigan

There was something about Cassandra that would not let him go. From the first, he held on to her even when she pushed him away. She was the one who doubted she would be enough to fill his needs. He insisted his roster of friends, parties and shared enthusiasms for folk art and music, would not threaten their closeness. For the first time he felt no desire to run. Six months into the relationship, they’d moved from casual content to talk of commitment. Cassandra balked. Perry insisted they take it slowly, carefully. He wanted to be careful with her, remembering what it felt like to be overwhelmed.

Cassandra had her own unaddressed but elusive wounds. Her early sexual abuse by her step-father, denied until this day by her mother, had not affected her ability to conduct her daily life as an office manager and mother of three cats. Impeccably dressed during business hours, she was happy to lounge around in sweats on weekends.

Perry found her Nordic good looks irresistible.

Cassandra preferred to stay home, and to avoid unfamiliar social situations. Naturally social, Perry tried to accommodate her without giving up what he felt important for his own well-being. Cassie complained when he spent time hunting, fishing, or socializing with friends. Perry invited her to work on their issues in couples’ therapy. Cassandra appeared for several sessions and then declined to continue.

Perry appeared upset at our next weekly session. He’d caught Cassie going through his emails, and cell phone records. She responded by questioning him. He tried to field her suspicion of any communication with another woman, mostly in the course of doing business. Perry could say little to defend himself from her invective. He explained one of the women was an old friend. He assured Cassie that her suspicions were unfounded, but they continued even after he had provided explanations and alibis. This frustrated Cassandra even more. She couldn’t pin it down, but was certain he’d been unfaithful.

“There is no way to reason with her,” he told me.

Perry insisted that he couldn’t continue with her under these conditions. He was unable to fix what’s broken in Cassie. His partner of almost a year was forcing him out. He is full of grief.I try to comfort him, compliment his work on this relationship, regardless of the way it ends. It’s ground gained.

“What ground?”

In drawing close to Cassandra, I tell him, he’s glimpsed what it might be like to be loving and unafraid. While it doesn’t relieve his grief in the moment, this glimpse of who he might become, moves him.

.

What We Fish For

“Moonlight” 1886-1895 by Ralph Albert Blakelock

“Moonlight” 1886-1895 by Ralph Albert Blakelock

Parzival finds the Grail Castle at dusk following directions given to him earlier that day by a man he encountered fishing, who later awaits him in the Great Hall.Bathed, unarmed, and wearing a white robe, Parzival follows a maiden similarly robed to the banquet. He is struck by the scale of the hall, and the abundance of the table at which he is seated. The Fisher King, on the divan beside him, engages him briefly, then cries out in pain. As in a dream, Parzival cannot hear or see his host clearly. The procession displaying the Holy Lance and Grail leaves him in awe. He has only a limited awareness of anything else. Under the spell of these numinous objects, the underlying meaning of the spectacle eludes him. He registers the signs of anguish in his host, deepening furrows, compressed lips, but he has been taught as a knight not to question his host. Parzival fails to ask the Fisher King the healing question. In a state of satiety and confusion he is abruptly taken back to his chamber. He has no idea of the disappointed expectations he’s left behind.

Only years later, after Parzival has felt the weight of his own grief would he be able to fully acknowledge the grief of another. Until that time, he remains tongue tied, buried in false assumptions, and burdened by failure.

It’s not unusual at some point to find ourselves dumbfounded at the banquet of life. A few of us glimpse the image of our unique destiny. Though it may not be fully recognizable, it propels us into the larger mystery of the consciousness—the field from which form arises. The Glimpse, however it appears to us, activates feeling and intuition, a drive to grasp what waits to be named before we can name it.

.

The Glimpse

Parzival, too, has such a glimpse shortly after he first arrives at the Grail Castle. On his way to the banquet hall he stops in front of a small room on his left. The grey bearded elder lying there lifts his head to meet the young knight’s eye.Parzival feels something familiar stir. The old man seems to float on a bed of light. Suddenly Parzival’s heart is filled with tenderness, an emotion he has not encountered before. He wants to find out more about this man, and learns only that his name is Titurel, before the attendants urge him on to the Great Hall, the scene of his epic failure.

“The Wounded Fisher King”

“The Wounded Fisher King”

In the morning no one is present in his room or the corridors. His horse awaits but there are no other horses in the stalls. The castle appears empty. He hears jeering from the walls as he rides out. They accuse him of lacking a heart as well as a tongue. The draw bridge closes behind him. Parzival begins to suspect he is the object of derision. Unseen voices mock him from the battlements, ask why he failed to ask the question.

“What question?” he calls back.

What follows is confusion. The nature of his offense eludes him, until after riding for several hours be encounters a women keening over a dead knight. She reveals herself to be his cousin, Sigune. The corpse she holds, and refuses to let go of, is her lover who died in defense of Parzival’s kingdom during his absence. This corpse is just one of many who have died for his sake, some by his own hand. She then makes clear the depth of his failure to ask Amfortas the healing question. Parzival is struck dumb. What he imagined to be a legacy of noble deeds is in fact a list of failure upon failure.

Parzival has failed because he is unconscious. His mission had been a vague thing, and his intervention the consequence of his inherent knightly virtue. He has yet to learn the whole truth about himself, and the role he must play. The fact that he may be part of the Grail lineage has at no time crossed his mind. Not even as he rode away, or registers the truth as Sigune details it to him.He rides away leaving her with her corpse, the Waste Land unchanged.

What he did take with him was the feeling evoked by his memory of the old man on a bed of light in the room off the corridor. That glimpse had been accompanied by an emotion that connected him to the object of his gaze in a way he could not have understood—that he had in that moment made contact with the original Grail King, his great uncle, Titurel.

The importance of The Glimpse must be noted; it’s a crucial milestone in Parzival’s development. The Glimpse activates the process of becoming conscious. It will take Parzival twenty years of wandering, struggle and disappointment before he will realize his destiny.

What might he have registered upon seeing Titurel through a crack in the door?

For Parzival, this glimpse is accompanied by a compelling new field of emotions. Perhaps it’s what he saw mirrored by that senex, the wise ancestor who has known the end from the beginning. Did Parzival glimpse himself, redeemed, in the loving gaze of the original Grail Keeper, hidden in a room of the unconscious?

My client Perry, as well, might early on have glimpse the possibility of his redemption in the Cassandra’s loving gaze, or projected that potential on to her. Like Parzival, he may have experienced in that moment the promise of a compelling new emotional field offering something he had never experienced before. Both Perry and Parzival felt rather than understood the depth of this connection, though neither could have explained it.Perry, like Parzival, drawn to that part of himself he struggled to imagine, the part that makes one whole, what we fish for, color flashing under the surface, Osiris’ phallus swallowed by a fish.

.

Enter the Fisherman

Perry is a life-long fisherman. He is at his best on the bank of a trout stream casting out line. His years have taught him to read the water for patterns, flow and bottom. Perry chooses his lure carefully, and knows where and how to place it. In our sessions, we talk about his dreams in the language of fishing. It has made the symbolic references of the exploration easier to understand.

Dreams and lucid visions hit Perry’s line regularly. The catch can be playful, or smart, or if he is not attentive, it can easily snag and break the monofilament.He is however quick to tell me that fishing for dreams differs significantly from what he does at a trout stream in one respect. Fishing for dream content, he is at times repelled, and at others fascinated by what he reels in. But certain things hold true for both.

“I don’t always catch something, or keep what I catch.”

I ask Perry if he ever throws the most remarkable images back.

Perry smiles. Clearly fishing for trout holds none of the potential dangers inherent in fishing his dreams. The sense of utter vulnerability is absent. The variables are inviting rather than confusing. He loves getting lost in the senses. He insists that standing in the stream, knee deep in waders, watching light and shadow shift along the banks, hearing the current murmur, feeling a breeze touch his cheek, make the experience sufficient unto itself. Some of his finest days are those when he doesn’t get a bite.

This may be true for the Fisher King as well.

I read between the lines. The problem arises fishing in psychological space/time, in which the depths rise up. Perry gets scared when a submerged danger is about to break the surface.“Can you pull in Leviathan with a fish hook, or tie down its tongue with a rope?” says God in Job 41. When Perry hears that voice his habit is to take a break from therapy, women, and socially uncomfortable gatherings. Even a fleeting glimpse of what might be brought up from the depths, imprinted with the numinous, can be deeply disturbing to one who is unprepared.

Most spiritual traditions warn against it. In the Jewish tradition, Merkabah mystics are warned to avert their eyes, never to gaze directly at the Throne, lest they instantly become a cinder. Only a divinely ordained but clinically mad Ezekiel, or Moses on the mount cautioned where to gaze, can risk drawing close to the ineffable. God warns Job directly not to stare too deeply into the depths where numinous power exists as the Leviathan:

“L’ Ange de Foyeur,” by Max Ernst

“L’ Ange de Foyeur,” by Max Ernst

His snorting throws out flashes of light; his eyes are like the rays of dawn. Firebrands

stream from his mouth; sparks of fire shoot out. Smoke pours from his nostrils as from aboiling pot over afire of reeds.

.

The Fisherman’s Lament

“I feel empty,” Perry opens our session. “Nothing seems to last. Nothing of value.”

I hear Parzival cast back into the Waste Land.

In Perry’s case, the Waste Land is a workshop he participated in along with other real estate brokers who deal in multi-million dollar properties facilitated by a noted motivational speaker. After briefly assuring them all that they were a dynamic group of high achievers, she challenged them to close their eyes and picture what success looked like to each of them. More specifically, she wanted to know how they saw themselves at the height of their success, and what they would choose to do with their money. It was meant to be a goal orienting exercise, a glimpse of their destination, the longed-for reward each worked so hard to realize.

“I started to cry.” Perry flushed.

“Why?”

For him, this was a glimpse of the abyss.

“Unbecoming in a man after forty-five.”

“What do you make of it?”

“I don’t know.” He rubbed his chin, a Perry tell expressing stress. “They keep urging us to reject pain, and embrace pleasure. But for some reason, I’m always moving in the opposite direction.”

I repeat Victor Frankel’s contention that for most people the dream of material wealth fills the void left by the absence of meaning. Perry has read Frankel’s Man’s Search for Meaning, and agrees. Still, it is hard for him to let go of the material dream. On the other hand, after so much time pursuing it, material success feels meaningless to him. Surrounded by those at the workshop, all of whom are driven by the desire for wealth, he became nauseous, and frightened he’d throw up.

“Maybe that’s a good thing,” I offer.

“Easy for you to say. But where does it leave me?”

Perry’s attempt to fill his inner emptiness with intimacy had produced the same reaction. The recent breakup with Cassandra left him almost permanently nauseous. He had been determined not to follow his past pattern to run away when things became difficult. And he had held firm until the accumulated weight of her accusations had forced him out. She had constantly misread his slightest look as flirtation with a waitress or woman on the bus, continued to check his phone and computer logs. At every turn, Perry found himself litigating in his own defense, attempting to show her that she was mistaken, he was not her predatory step-father.

She would not be persuaded.

“I don’t understand how the nurture and trust I offered a partner for the first time in my life, provoked so much anger and suspicion.”

“Focus on her pain for a moment.”

“The Wounded Angel” by Hugo Simberg

“The Wounded Angel” by Hugo Simberg

This is the only way he will be able to ask the healing question.

“I can’t!”

“Because your pain gets in the way.”

“Yes,” he nods. “If only I could get rid of this neediness, kill that part of myself…”

“No, no. You don’t want to do that.”

I suggest that killing feelings rather than understanding them is no solution. There is meaning in pain. To deny it invites substitutes like the pursuit of material wealth and power to fill the vacuum.In time he will be able to separate his pain from hers, and at that point see her more clearly

He confesses to drinking too much.

I tell him to watch his dreams.

“Maybe I’ll go fishing.”

“Good idea,” I reply. “There’s something healing about casting that line, just floating the lure.”

Perry knows I’m talking figuratively, about dreams. He nods, then winces—Parzival hearing the castle gate close behind him.

“I’ll call you,” he says.

.

Dressing the Wound

Perry calls two weeks later for an appointment.He hasn’t had the energy before this for a session, but is determined not to run away. There is too much confusion surrounding the situation. He’s ready once again to talk about his dreams. And there is one in particular he wants to explore.

I look forward to the meeting. Perry’s dreams are fluent. His unconscious is often visionary, personal issues enriched by symbols and archetypal content. Facing me from the couch, his back ramrod straight, he recounts the dream that sent him here.

I’m standing in front of a green curtain that slowly transforms into a face, one I find frightening. At first it is mostly a large mouth, like a tear in the fabric, except it grows lips. Then the other features press against the surface as if they are trying to fix themselves but can’t. The surface is wrinkled like an old cloth. Then it becomes transparent, and parts. I hesitate, but can’t do anything else than step through it, and find myself in a cave. There’s a waterfall at the far end. It falls into a pool, the kind where wild animals come to drink. There may even by foot prints at the edge. Then I notice a fountain at the center of the cave. Water spills from a circular dish into a catch basin. The sound of water falling surrounds me. Musical, almost harmonic. With so much water and stone, the cave isn’t damp. On the contrary. I can feel a breeze which is surprisingly dry and sweet smelling. I start to relax, even sink into a peaceful state, until I sense something watching me, a powerful presence; it seems to be everywhere. I wonder if it is malevolent, means to do me harm. I’m sacred, but fascinated, wait for whatever is watching me to speak. But it doesn’t. There is only silence. I am stuck to the spot. Can’t move. Finally I summon the courage to call out, “Declare yourself!” As soon as I do, the whole scene fades and I am facing the green curtain. The surface wrinkles, lips form then answers me: “I’m here!”

Perry recalls every detail. He had visited a place where his senses registered changes like seismographs. Hyper-reality, he calls it. It was clearer to him than any other concrete place he had been in recent memory. He wondered if what he experienced had been a form of possession, and the presence he felt there with him a demon.

“What you entered,” I suggest, “is a sacred space. Jung refers to it as a temenos.”

“What’s that?”

A temenos, I explain, is an eternal dimension within the psyche. Reflected in its geometry—the circle squared—the temenos refers to a center of personality. It is a space that contains the realized self. As an archetypal form it’s describes the classic mandala. It is commonly expressed in the design of most plazas, a circular fountain at the center of a square. King Arthur’s Round Table is the temenos at the center of Camelot. In Perry’s dream, it’s presented in its archaic form, a fountain at the center of a cave in which the air smells sweet and without dampness, though full of running water.

Perry’s eyes grow wide, Parzival in the presence of the Grail.

“I was terrified,” recalls Perry. “Like I might die.”

“You had a glimpse of wholeness behind nature’s curtain. The green mask of the Great Mother, which you’ve mistaken for a demon, has assured you from disembodied lips that she’ll be there to receive you again, when you’re ready.”

“I guess.”

“Remember what she said?”

“Sure. She said: I’m here!”

.

Gone Fishing

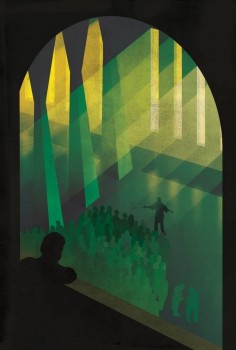

“King Arthur’s knights, at Pentecost, see a vision of the Holy Grail’. From Lancelot and the Holy Grail.

“King Arthur’s knights, at Pentecost, see a vision of the Holy Grail’. From Lancelot and the Holy Grail.

Perry cancels his appointment the following week, texts that he’s not “running away,” just wants to spend an indefinite time trout fishing. It’s the start of the season, streams are stocked. His gear is packed. We both understand what this means. I hope that in addition to catching trout, he will pull something else out of the deep pool of his sleep. Maybe the Oxyrhynchus, the fish which the Egyptians believed swallowed the phallus of Osiris.

“’Ripeness is all,’” I text him back.

When I see him two weeks later, he reports the following dream.

I am fly fishing in a stream surrounded by high banks of exposed roots from the trees above. Suddenly I feels a tug at the line, pull back, set the hook, then try to reel in, but the line is heavy and appears stuck on the bottom. I give it a tug. The line becomes free, but there is a significant weight on the other end. It doesn’t fight or run, but requires enormous exertion to move. Eventually I can see a shadow in the water, and then make out this huge brook trout, many times the size of a normal one. As it comes closer I notice there are a lot of little fish attached to it, feeding on it. When I lift him out of the water, the small fish fall away and the trout comes up clean. I see that its nose is slightly bent, which happens to very old fish, and that it has a mouth full of razor sharp large teeth. But I’m not scared to touch it. Maybe because it doesn’t resist in any way. I lay it out gently on the bank. It doesn’t try to bite me. I am confident that it won’t hurt me, and my heart is suddenly full of a mixture of sadness and joy, wide open, raw, with an overpowering emotion I realize is love.

Perry shakes his head, still in the grip of that emotion. The dream unfolds of its own accord. Before he says a word, we share an understanding of this one. What he catches in the dream is no ordinary fish, but his wounded core. This ancient creature has been buried in the sunless depths of his soul all his life. It has grown old inside of him. Because of his determination to confront his pain, and our work together, because he is a fisherman who has kept his line in the water, the fish chose to emerge at this time.

“Swordfish,” Brunetto Latini’s Livre de Tresor

“Swordfish,” Brunetto Latini’s Livre de Tresor

He will always experience it, even as a memory, in the present. It waits in the shadows of the stream, where Perry is likely cast his lure. At first the creature hugs the bottom, low enough to resist being pulled up, but eventually allows it. Perry is struck by an unexpected emotion: he feels tenderly about the creature. The feeling grows stronger as he reels. He is moved by the sight of creature’s bent nose, an indication of its age.

“Very old,” he repeats.

Its eyes are large black holes that glow, like one of those blind fish that live near thermal vents at extreme depths where there is no light, it is a perfect formulation of his woundedness. Clusters of smaller fish clinging like barnacles fall away as Perry lifts it out of the water. These he recognizes as collateral conditions that fed on his pain. The creature, too, seems relieved to shed them, revealing the iridescent hues that were hidden, green and blue, visible in the daylight.

The emergent form and details of his ancient sorrow, what had been shapeless terror now given shape, gives him palpable relief, almost a lightness of being. He spreads his catch on the bank, whole and clean; its razor sharp teeth pose no danger to him. In the light of making so much material conscious, Perry sees through a clear lens.

He admires the fish where it lies, old, venerable, then drops to his knees overwhelmed. What he registers in the creature’s blind eye pierces his heart like blade.As Parzival discovered by “piercing through,” there is no greater intimacy than the gratitude that opens when the hardened accretions that feed on despair fall away like old barnacles. His heart swells like a vessel unable to contain its contents, so full it is about to spill over. Perry is convinced that he will never love anything more than he does this old fish at his feet.

.

Daedalus Delivers

Gypsy’s Diner

Gypsy’s Diner

I am sitting at Nick’s tasting the last of my toasted bran muffin, getting ready to record last night’s dream in the notebook open beside the coffee mug veined with grime that will never wash out. There are a few regulars at the counter: and ambulance medic named Bob, a beefy man in a blue official jacket; Yuri, the scientific chiropractic Ukrainian masseur, and the old man who makes duck noises. Outside, homeless men fresh from the shelter on 3rd Street make their way slowly down Second Avenue, find empty doorways, talk to themselves in front of the Emigrant’s Bank on the other side of the street.

I remember last night’s dream clearly, a fragment, but as if it were a lived experience—as real as my memories of Vietnam, or my Brooklyn childhood around the corner from Ebbets Field.

I am looking at a man walking quickly from Gem’s Spa towards Houston Street along 2nd Avenue. He is casually dressed in jeans, and s black sweatshirt on the front of which embossed in white block letters the legend: “Daedalus Delivers.” I note his purposeful walk and repeat the words on his sweatshirt, then conclude that he is a messenger on a mission. I repeat the phrase, “Daedalus Delivers.” Then answer: “And he does.”

It will take me months, maybe years, to understand that the messenger is the message of this dream. As such, the dream possesses an origin and an intention, a way of delivering the message. Everything speaks of an intelligence at work that is independent of our own, what Jung refers to as the Objective Psyche, and the Romans understood to as the Genius. Here, the intelligence alludes to itself as Daedalus, the mythic craftsman who constructed the labyrinth on Crete to contain the Minotaur.

It is a dream that comments on itself and the very archetype of The Dream. In the meta-sense it points to the idea that in its construction a dream is a labyrinth which conceals something at it center that may be monstrous or grotesque, a concealed mystery waiting to be revealed. The indication is that it contains a core-meaning that must not be seen directly, in day light. The creature/meaning in question, sensed, even suspected, lies buried beneath the heart of the city.

Daedalus, the inventor of wings that can simulate those of birds, carry one as in a dream high above the ground over great distances. On the other hand, like the unchecked dream, it offers a perilous power for those like his son, Icarus, who are temperamentally unsuited to flight.

This early dream image flourished in my storehouse of images, and proved so rich it survived three decades undiminished. Attached to it the smell of old urn coffee, and another artificer, Nick, guardian of my morning ritual in the temenos that is his diner. The Racing Form from which he seldom looks up challenges him daily with the riddle of fate vs free-will, what can be calculated and what escapes the scope of probability.

His presence was a secure incubator, a place where the images could emerge from my night-sea journey like companions on the boat I steered into the morning, collaborators in the unfolding of my own hazy destiny. Nick made me feel we shared this purpose. His old watery eyes when I left followed me out the door, and into the room where I practice today with other peoples’ dreams as well as my own.

I have learned patience in this pursuit.

For one thing, my boat is more stable, and the lines steady. I fish for what informs me in science, as well as in the humanities and the arts. My navigation skills have been honed by survival years on the lower East Side, in embattled zones of South East Asia and Central America. But there has been no better place to cultivate the clues to judging depth, or the potentials of a weed line than in a marriage, or parenting a child. And by my every reckoning, as well as those of my clients, I remain convinced we possess a submerged intelligence that generates messages that form and transform the patterns governing our lives.

Which is why the Fisher King addresses his pain by fishing.

“Emblema XXI” by Michael Maier, 1618

“Emblema XXI” by Michael Maier, 1618

He demonstrates what it means to float on the unconscious. Just to knowingly touch its vastness brings comfort.This is true for all who troll the field from which form emerges. Sooner or later, those waters will yield what we must see. Many are sustained by that promise. A few, like Perry, fish only to feel the late afternoon breeze, and light on the water.

There’s no faith or institution necessary, nor any need to convince another of the experience of the inner intelligence, what the Roman’s called the Genius, is available to you. It is numinous, and one can use the language of myth to describe it. My dream at Nick’s diner named that intelligence Daedalus, after the Greek artificer. Socrates said he failed to listen to his Daemon to his detriment. European romance refers to it as the Grail, or the Philosopher’s Stone that can confer immortality.Carl Jung referred to it clinically as the Objective Psyche, or the Self. Like the Hindu Brahman/Atman it is embedded in our psyches, and in the universe at cellular and cosmological level. What we may experience in our waking mode is that intelligence can evolve slowly starting with the early wound, separation from the womb/mother, to the possible apprehension of the ground of consciousness itself, a glimpse of which opens the heart as it did for Parzival and Perry.

“The Voyage of Life,” by Thomas Cole

“The Voyage of Life,” by Thomas Cole

The ancient fish representing Perry’s unconscious suffering spread out on the bank in his dream, is a message from the same Objective Psyche as my Daedalus in his black sweatshirt walking briskly down Second Avenue. Both convey a touch of the numinous. The Grail which sustains the banquet Parzival observes is also a representation of the intelligence that spills dream images into our sleep, as is the stranger in the boat who directs him to the castle. A glimpse of this reminds us that we are everyone in the dream. Each of us is Parzival, challenged to heal the Fisher King; each of us a Fisher King waiting for our Parzival, as well as the fish who has swallowed Osiris’ phallus swimming in the sea of consciousness. Every morning, I write down what I’ve brought back from the dark waters over coffee, absent the toasted bran muffin, and Nick—whom I failed to engage directly, and ask the healing question.

—Paul Pines

.

Photo by Jay Hunter

Paul Pines grew up in Brooklyn around the corner from Ebbet’s Field and passed the early 60s on the Lower East Side of New York. He shipped out as a Merchant Seaman, spending August 65 to February 66 in Vietnam, after which he drove a cab until opening his Bowery jazz club, which became the setting for his novel, The Tin Angel (Morrow, 1983). Redemption (Editions du Rocher, 1997), a second novel, is set against the genocide of Guatemalan Mayans. His memoir, My Brother’s Madness, (Curbstone Press, 2007) explores the unfolding of intertwined lives and the nature of delusion. Pines has published twelve books of poetry: Onion, Hotel Madden Poems, Pines Songs, Breath, Adrift on Blinding Light, Taxidancing, Last Call at the Tin Palace, Reflections in a Smoking Mirror, Divine Madness, New Orleans Variations & Paris Ouroboros, Fishing On The Pole Star, and Message From The Memoirist. His thirteenth collection, Charlotte Songs, will soon be out from Marsh Hawk Press. The Adirondack Center for Writing awarded him for the best book of poetry in 2011, 2013 and 2014. Poems set by composer Daniel Asia have been performed internationally and appear on the Summit label. He has published essays in Notre Dame Review, Golden Handcuffs Review, Big Bridge and Numéro Cinq, among others. Pines lives with his wife, Carol, in Glens Falls, NY, where he practices as a psychotherapist and hosts the Lake George Jazz Weekend.

.

.

.

.

Jared Carney is a writer, director, producer, and production designer with Creeker Films from Fredericton, New Brunswick, and is a graduate of Film Production from the University of New Brunswick. He is a Features Writer for Horror-Movies.ca and just recently wrapped his 9th film, a Stephen King adaptation entitled “The Man Who Loved Flowers”. The horror genre in particular has always piqued his interest and many of his influences stem from both classic and new-age horror cinema.

Jared Carney is a writer, director, producer, and production designer with Creeker Films from Fredericton, New Brunswick, and is a graduate of Film Production from the University of New Brunswick. He is a Features Writer for Horror-Movies.ca and just recently wrapped his 9th film, a Stephen King adaptation entitled “The Man Who Loved Flowers”. The horror genre in particular has always piqued his interest and many of his influences stem from both classic and new-age horror cinema. Nicholas Humphries is an award-winning director from Vancouver, Canada. His accolades include Best Short at the Screamfest and British Horror Film Festivals, Audience Choice at the NSI Film Exchange, a Tabloid Witch, an Aloha Accolade and a Golden Sheaf. His films have been nominated for multiple Leo Awards, have screened at Grauman’s Chinese and Egyptian Theaters, on CBC, Fearnet, SPACE Channel and in festivals around the world. He is also a director on the acclaimed Syfy digital series, Riese: Kingdom Falling, which was nominated for four Streamy Awards, three IAWTV Awards and a Leo Award. Riese was also an Official Honoree at the 2011 Webby Awards. His feature film credits include Death Do Us Part and Charlotte’s Song (2015). He teaches Directing at Vancouver Film School.

Nicholas Humphries is an award-winning director from Vancouver, Canada. His accolades include Best Short at the Screamfest and British Horror Film Festivals, Audience Choice at the NSI Film Exchange, a Tabloid Witch, an Aloha Accolade and a Golden Sheaf. His films have been nominated for multiple Leo Awards, have screened at Grauman’s Chinese and Egyptian Theaters, on CBC, Fearnet, SPACE Channel and in festivals around the world. He is also a director on the acclaimed Syfy digital series, Riese: Kingdom Falling, which was nominated for four Streamy Awards, three IAWTV Awards and a Leo Award. Riese was also an Official Honoree at the 2011 Webby Awards. His feature film credits include Death Do Us Part and Charlotte’s Song (2015). He teaches Directing at Vancouver Film School.

Bill Hayward

Bill Hayward Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan Fragment A (from the film Asphalt, Muscle & Bone)

Fragment A (from the film Asphalt, Muscle & Bone) Broken Odalisque

Broken Odalisque Al Pacile (from The Human Bible)

Al Pacile (from The Human Bible) Dragon Smoke Behind Tree

Dragon Smoke Behind Tree

![chaim-soutine-by-Tekkamaki[68597]](https://numerocinqmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/chaim-soutine-by-Tekkamaki68597.jpg)

Whirlpool galaxy,

Whirlpool galaxy,