Chantal Gervais, Karsh Award 2014 recipient. Photo Credit: Jonathan Newman

Chantal Gervais, Karsh Award 2014 recipient. Photo Credit: Jonathan Newman

One thing does lead to another and several vectors converge in Chantal Gervais’ body of work from over the past twenty or so years. Look at the big picture of Gervais’ mostly photographic art projects. A strange inter-connectedness emerges starting with her studies of the human body. Through photography she exposes its external strength and frailty in Duality of the Flesh (1996-1997), The Silence of Being (1998-2000), Without End (2003), and Between Self and Others (2005). She then focuses on her own body, starting on the outside using a flat bed scanner to create her version of Da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man, and with a further shift from photography to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to expose herself from the inside out in Les maux non dits (2008 – present).

Her video, Self-Portrait (part of the Les maux non dits project), is a finer distillation of that inner self-exposure, and a more personal take of the Corps exile (1999) video of bodies floating, suspended and moving in white light and grounds. And then there is her look at how other life forms suggest intimate parts of the (female) human body as represented in Les bijoux de la chair (1997), and ten years later, in Études de bivalve, a display of splayed bivalvia close ups.

The converging trajectories of the human body explored outside and in, the videos, and the other life forms as representations of things human, appear quite strikingly, if not symbolically, in Transformations, Gervais’ first attempt to document the metamorphosis of the dragonfly from the alien-looking nymph. Where will she take it next? I asked her and she told me when we met at the Karsh-Masson Gallery where her work was exhibited as part of her being the recipient of the City of Ottawa’s 2014 Karsh Award.

Chantal Gervais teaches visual arts at the University of Ottawa and at the Ottawa School of Art. She enjoys engaging in constructive and critical discussions with her students about art and their work. One of her former students, Ottawa artist Virginia Dupuis, found her to be “highly engaged, focused and curious” making Gervais to sound more like a student than a teacher.

Gervais’ undergraduate studies in the fine arts were an eye opener for her. She started in realistic drawing and became attracted to photography as she saw that both art forms required a great level of observation of the world we live in, and photography began to develop in her. Now, in her artistic practice, she pushes the boundaries of that medium by working with flatbed scanners, MRIs, and multichannel videos.

Calling Ottawa home, Gervais grew up in Val-d’Or, in the Abitibi-Témiscamingue region of Québec. She graduated from the University of Ottawa in 1993 with a Bachelor in Fine Arts (photography), and four years later completed a Master of Arts degree in Art and Media Practice, at the University of Westminster, UK.

—JC Olsthoorn

/

Transformation 4:33 minutes, Single-channel, (2014)

JC Olsthoorn (JCO): While watching your video installation, Transformation, just outside the Karsh-Masson Gallery proper, I realized that I didn’t know dragonflies emerged from an alien-like creature, a nymph. Perhaps I should have paid more attention in biology class. You mentioned to me earlier this piece is a first version. What prompted you to create it?

Chantal Gervais (CG): The metamorphosis of the dragonfly made me marvel when I saw it for the first time at the cottage. This radical change of living environment from water to air of the nymph changing into a dragonfly made me think of the human body, from birth and beyond. I was fascinated with the process, the vulnerability, the delicateness of its body and its strength, resilience, and all the energy as well as the raw physicality of the insect going through its extreme transformation. Also, the insect seems to get sporadic spasms just before the dragonfly emerges from the nymph. This whole series of events reminds me of how we are going through different physical and emotional stages through our life – but here it is happening in a very short period of time – yet this insect is one of the oldest on earth. I believe it has been around for 300 million years. It comes from so far away, from so long ago. It’s incredible. There is something really astonishing and ritualistic about all this.

At times the dragonfly reminds me of mythological and religious figures found in Western art history. I can’t say exactly what it is yet, but that’s one of the aspects that I will reflect on further. At every moment, the insect seems unbearably at the mercy of any predators and its surroundings. It appeared extraordinary when it made it through its metamorphosis, but then the water got agitated by passing motorboats. After all this, in an instant a wave was going to end it. That is when the dragonfly flew away!

JCO: And the connection you see to your other work, other processes?

CG: I see the link with my quest to explore the human body as a vessel of lived experience, and my interest in a representation of the body’s corporeality that conveys intense physical and emotional states. I have always been inquisitive of transitional states, and so is my interest with the inside-outside boundary of the body which I find exquisitely explicit and tangible with the dragonfly.

If you look at my early series, The Silence of Being, I used chiaroscuro lighting and cross processing to accentuate the corporeality of the body such as discolorations or blemishes on the skin.

Untitled #4 from the series The Silence of Being,

Untitled #4 from the series The Silence of Being,

126 x 96.5cm, Chromogenic print (1998)

With Between Self and Other, the people I photographed had experienced radical changes to their bodies as a result of surgery, accident and aging. So again, it’s the inside speaking on the outside. There’s something about the relationship between the inside and the outside of the body that I find fascinating.

Untitled #5 (Marina) from the series Between Self and Other,

Untitled #5 (Marina) from the series Between Self and Other,

101.6 x 315cm

3 print of 101.6 x 101.6cm, 3 Chromogenic prints (2005)

JCO: There are linkages and I get a sense of optimism from what you are saying. We have an insect that dates back 300 million years, one that is quite fragile and vulnerable as it transforms. Where are you planning to take it next?

CG: I want to connect it somehow to the human body. I’m not sure how yet. Technically, I know that the recording has to be executed better. The images are too shaky so I will re-film it using a tripod. When recording it, I found myself wanting to capture the transformation from all sides simultaneously. For the next version, I’ll probably use more than one camera with them positioned all around the insect.

I’m not sure yet of its final presentation. Perhaps multiple large-scale projections? When I redo it, I want it to be more poetic. I find it didactic now. Maybe that’s the “educational” that’s coming across. I want it to be a metaphor of the mystery and the complexity of the human body.

There’s a fine line, a red flag for me. As a nature show, it presents the development of the nymph into a dragonfly from beginning to the end and that’s one of the things I worried about. But in the meantime, I was torn because I felt that it was essential to include its complete metamorphosis.

JCO: It doesn’t work the same way as, let’s say, in the video projection Self-portrait from the series The Body Ineffable (Les maux non dits).

Self-portrait from the series The Body Ineffable (Les maux non dits),

1:58 minutes excerpt | 6:28 minutes (looped), Life-size video projection (2010)

CG: In The Body Ineffable video projection, the technology has an immediate impact on the way the subject is performing. The work engages how the technology transforms how and what we see. I mechanically and impartially mapped my body in numerous short 2 minute videos I re-assembled together and layered with the MRIs to reconstructed it.

JCO: Opening yourself up to being scanned or photographed, opening your or someone else’s space for the very different aspects of exposure sets up a vulnerability, does it not?

CG: It is interesting how the content of my work with time became closer and closer to me. I started by photographing professional models for the series called The Silence of Being. After that, I was working with friends and friends’ family members for Between Self and Other. I then turned the camera onto myself with The Body Ineffable and my late father, or rather, the relationship with my father, with the work called Portrait of my father Paul.

What sets up the “vulnerability” is the high level of observation often engaged in my work, not so much the fact that it became closer to me. It happens through the different ways I choose to map, observe, and image different experiences of living. With Between Self and Other, each individual is composed of three photographs, which depict different views of their bodies, which have moved slightly during the same photo shoot. Looking at the composite, these people exist in viewer’s mind, not as a fixed image but a body in continuous movement. Hopefully it keeps a sense of their subjectivity and challenges their objectification. The photographs’ reference to various pictorial genres is also significant…close your eyes and think of someone who is injured or an elderly person…what do you see? I hope the image in your mind is nothing like the photographs included in the series Between Self and Other!

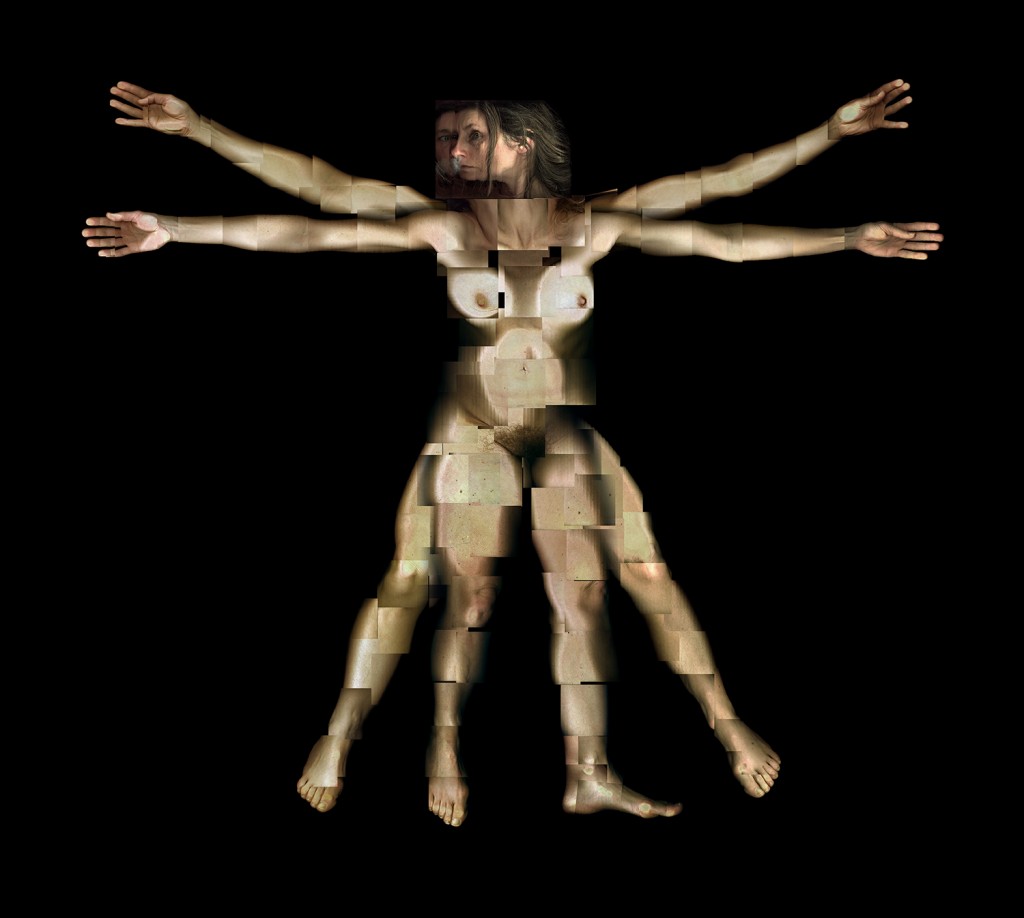

Vitruvian Me is also a composite, one inspired by Vitruvian Man by Leonard Di Vinci. This work is part of The Body Ineffable, which includes a series of self-portraits created from MRIs of my body. When I was in the MRI machine I thought it would be interesting to create an ambiguous border between the interior and the exterior of the body so I scanned myself piece by piece using a flat bed scanner. I then reassembled them in Photoshop. The performative aspect of this work is an important part of the piece. The process involved mechanically and rigorously scanning 4 inch squares of my body to transcript and to compare the composite of scans to the drawing. In doing this, I performed and played with the idea to contain, control, immobilize and decontextualize the body in order to understand it.

Vitruvian Me from the series The Body Ineffable (Les maux non dits),

Vitruvian Me from the series The Body Ineffable (Les maux non dits),

88.9 x 81.3cm, Inkjet Print (2008)

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man via Wikipedia

Leonardo da Vinci’s Vitruvian Man via Wikipedia

JCO: Not a comfortable one at times.

CG: No, but it was kind of funny at the same time. I’m a perfectionist. I made sure that every scan was captured properly to then be joined and lined up correctly. I redid it repetitively until I got it right. It is ironic to think that in the end I was never in that position itself.

JCO: It seems like a different type of objectification of the body in your work. Because it is an art piece, and a medical piece in a sense, there’s some distance. And there’s vulnerability.

CG: Yes, and actually my work has always interweaved elements of representations of the body borrowed from science, art and popular culture. With Vitruvian Me, there is a sense of proximity created by the fact that the skin, the scanner’s glass and the photographic surface are all intersecting at the same point physically. The flattening of the body against the glass accentuates its physical properties, and so conveys its vulnerability. And there’s a sense of closeness. It’s interesting because the work is extremely removed from what you see. Again, I’ve never been in this pose, yet it is very convincing.

JCO: There’s no static position. It’s comprised of many static images so you get movement from the “static-ness”.

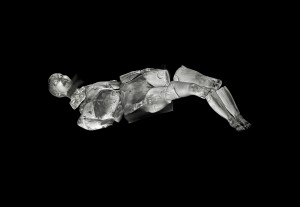

Self-portrait #6 from MRI from the series The Body Ineffable (Les maux non dits),

Self-portrait #6 from MRI from the series The Body Ineffable (Les maux non dits),

72 x 105 cm, Inkjet Print (2008)

CG: The same thing, in a way, with the images I took and joined together for Portrait of my father Paul. After he died suddenly, I was deeply moved by how the interior of his garage where he undertook various daily projects was impregnated with his presence. When photographing his space, I was sentimentally searching for him, wanting to hold in time what I knew was going to disappear forever. I felt overwhelmed, dispersed, lost and worried that I was going to miss something so I did photograph all around and everywhere and at various points of view. Afterward, I decided to present them as a composite to convey a more personal experience, more tangible, to evoke the act of looking or the re-enactment of being in the space, engaging the viewer to another level.

JCO: A hide-and-seek without looking for something?

Portrait of my Father Paul (2), 103.6 x 135.2cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

Portrait of my Father Paul (2), 103.6 x 135.2cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

CG: Or looking for somebody that you perfectly know is not there but is so painfully present As Lilly Koltun wrote so evocatively in her text “Why do we think people are where we bury their bodies?” (in “Surgery Without Anaesthesia: Chantal Gervais’ Corpus” by Lilly Koltun. The Karsh Award 2014 Chantal Gervais).

JCO: They are where we are, in a way. Because you are there, he is there. Which is really harder to capture, I suppose, but that’s very personal and that’s your own. As a viewer, we sense that presence, the presence of absence (or hiraeth), in a different way. Your memories are clearly here, your experience, yet it evokes in me memories I have, too, of similar experiences of my father.

Portrait of my Father Paul (6), 104.1 x 73.7cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

Portrait of my Father Paul (6), 104.1 x 73.7cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

CG: I’m pleased that the photographs encourage you to think of your own experience. The photographs depict a large quantity of things that my father accumulated over 37 years and so to convey a sense of searching and looking for him, there is one image that I think is important.

Portrait of my Father Paul (7), 104 X 228.9cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

Portrait of my Father Paul (7), 104 X 228.9cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

It’s a detail of photograph #7 of the series where I’m present, which allows to make the connection to my father. I just happened to wear a skirt that day. I don’t wear skirts very often. This was such a great coincidence to symbolically convey the connection between father and daughter.

Portrait of my Father Paul (7) (detail), 104 X 228.9cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

Portrait of my Father Paul (7) (detail), 104 X 228.9cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

JCO: And the imperfect fragments. You don’t try to overlap them so that they fit. There’s a disjointedness that works.

CG: I’m glad you say that because I did experiment with this. At first, I did overlap the images, changing their transparencies. But it didn’t work because I was weakening the sense of the physical aspects of his space. It became about memory in a metaphoric way. I was erasing the traces left behind by my father. Consequently, I decided to create composites using overlaps without changing the opacity, and including various perspectives and point of views of the same area. This way I keep the integrity of his space to testify my father’s existence in a way.

Portrait of my Father Paul (9), 111.1 x 228.9cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

Portrait of my Father Paul (9), 111.1 x 228.9cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

JCO: But the disjointedness has another effect, it makes us work a little bit as a viewer.

CG: And that’s important to me. I am interested in creating a viewing experience, which is active and not passive.

JCO: Exactly. And it’s also reflective of going back in terms of memory. Your memories are here, other people’s memories are here through their own interpretation. And memories are disjointed like that. We remember certain things and not others, so it’s not always transparent and congruous. There are divides to it and there are missing pieces and overlaps and interpretations.

Portrait of my Father Paul (11), 108.5 x 81.2cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

Portrait of my Father Paul (11), 108.5 x 81.2cm, Inkjet Print (2014)

CG: I am pleased that you engage in a reflective and personal manner with the work and that the photographs’ descriptive aspects have not led you to a literal reading of the space.

JCO: Is it the same with photographing the space of the human body, your own body?

CG: Yes, even with the video work. For example, the projection Self-portrait from the series The Body Ineffable I used the same approach of depicting systematically and precisely both the surface and the interior of the body. I had the idea for this work after completing Vitruvian Me. This work pushed my reflections about the body and how we perceive and understand the naked body in our society. It also made me think about the relationship between the audience and the body represented. I think to be able to engage with what the images can tell about ourselves, and questions their impact on our understanding of the body, I needed to be both the observer and the observed.

The video is kind of funny in some ways in how I became machine-like or puppet-like, and it could also be disturbing, even troubling in a way, too. Perhaps it humanized the experience and makes people connect with the person represented. Everyone will have a different reaction to it.

JCO: It’s a scan of everything inside and outside and in between

CG: That’s right. You have a woman that is naked inside out!

I spoke with two women when I was documenting my show here at the Karsh-Masson Gallery. One of the women really liked that piece. She had just come from a drawing class and was saying that she had never seen a naked body that is not beautiful. They’re all beautiful, she said, and the second you put clothes on, you perceive the naked body differently. You then decide: Some are beautiful. Some are not.

Isn’t that an interesting thought?

—JC Olsthoorn & Chantal Gervais

Chantal Gervais’ photo and video works deal with representation, identity, mortality and the relationship between the body and technology. Her work has been featured in numerous exhibitions across Canada and abroad. Solo exhibitions include Harcourt House Gallery in Edmonton; McClure Gallery and Vidéographe in Montreal; Galerie Séquence in Chicoutimi, Quebec; Art-Image in Gatineau, Québec, and Carleton University Art Gallery and Gallery 101 in Ottawa.

She has regularly spoken on her work at institutions including the National Gallery of Canada and the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA) in London, U.K. In 2104, she was the City of Ottawa’s Karsh Award recipient, and in 2002, the Canada Council for the arts’ Duke and Duchess of York Prize in Photography. Several Ontario Arts Council, Canada Council for the arts and City of Ottawa grants have supported her artistic production. She received a BFA in photography from the University of Ottawa and an MA in Art and Media Practice from the University of Westminster in London, U.K. She has been a board member at local artist-run centres including Daimon and Gallery 101 as well as teaching for over a decade at University of Ottawa and Ottawa School of Art.

§

JC Olsthoorn spends time at the Domaine Marée Estate near Otter Lake, Quebec, writing raw poetry, creating coarse art and cooking scratch food. His poems have been published in a chapbook, “as hush as us” and have appeared in literary magazines. JC’s artwork has been exhibited and has appeared in several publications. He is wrapping up a 30+ year career in communications and citizen engagement just in time to become a curator at the Arbor Gallery – Centre for Contemporary Art in Vankleek Hill, Ontario. His first show is the gallery’s sixth annual EROS 2015, an exhibition of Erotic Art, opening in February.

/

/