Numéro Cinq at the Movies readers should recognize Julie Trimingham’s name from one of our first entries when we featured her lovely, haunting triptych of films beauty crowds me, a pseudo-adaptation of the poems of Emily Dickinson.

In keeping with Numéro Cinq‘s penchant for reflecting on the creative process, NC at the Movies is asking filmmakers we’ve featured to reflect on why they make movies, what compels them to tell the visual stories they tell. Presented with that question, Julie Trimingham came back to us with a triptych (she likes to work in threes) of articles that look at her relationship with film: “Rosebud,” “The Horror,” and “Raising Hell.” This month NC at the Movies features her second article, “The Horror.”

— R. W. Gray

.

Part 2: The Horror

.

The horror. He says it twice. Marlon Brando’s hulking Kurtz in Apocalypse Now has witnessed and done things a person should never. I wish I could unsee the scalpeling of an eye in Un Chien Andalou. The severing of an ear in Reservoir Dogs. The rape in A Clockwork Orange. The flaying of a man in Red Sorghum. A thug in The Cook, the Thief, His Wife & Her Lover tortures a young boy by stuffing him with buttons torn from his apprentice cook’s white coat, and then finally the most awful button, the excised one from his own belly. Paul Newman swallowing too many hard boiled eggs in Cool Hand Luke leads to him digging his own grave at the end. Nicolas Roeg’s Walkabout begins with a man trying to kill his children. A diligent boyfriend’s investigation into the disappearance of his girlfriend in the Dutch film The Vanishing ends with him, and us, finding out what happened by sharing her fate: buried alive with no hope of escape. Celluloid images of brutality –nightmares – are belched up from our species’ shadow side.

Part of me wants to cling to Anne Frank’s belief that we are all good at heart; another part wants to figure how it is that all these good hearts are involved with genocide, murder, torture, stupid wars, as well as more intimate and prosaic barbarities. It is a question against which I bang my head. My son, now in kindergarten, has suggested that the good people should kill all the bad people in the world. I am become death, destroyer of worlds.

Australian security recently reported that they had broken up a plot in which zealots would randomly seize people of the streets of Sydney, cut off their heads, and videotape the killings so all the world could see. The White Rose, an intellectual, non-violent resistance movement, bloomed in Munich in the early 1940s. Comprised of university friends, the group anonymously wrote and distributed leaflets that decried Nazi policies. Sophie Scholl, a girl of 20 who loved hiking and books, children and God, was one of these activists. I clap my hand over my eyes as she is beheaded by Nazis in the film that bears her name.

Nor can I bear to watch the beheading of Thomas More in A Man for all Seasons, the beheading of King Henry’s smart, proud queen in Anne of the Thousand Days, the beheadings of Daniel Pearl, of James Foley, of Steven Sotloff, of Hervé Gourdel in virally distributed jihadist propaganda film clips.

Even when unseen, these scenes have made their way into me as if I have swallowed dark pills. Does it matter that some are fiction, some historical dramas, some news, some threats? Yes, but the images are all queasily spliced together in my mind; they describe the same arc of an unjust blade.

Aristotle would have us feel cleansed by tragedy, scrubbed by pity and fear. Screaming, crying, gasping at something that happens on screen allows our bodies to release some of the horror we feel simply because we’re human, because suffering exists, because the world is as cruel as it is beautiful. Too, the dramatic form is a container for collective emotional experience, a means by which we can feel connected, if briefly, to one another. We can mourn together. We can vicariously survive the tragedy, and come out the other side. We can empathize with the protagonist who, by dint of pride or error, has come to a sorry end. If Anne had held her tongue, if More had signed the oath, if Sophie had discreetly distributed the tracts rather than flinging them into the air, they all would’ve kept their heads. We all screw up and behave foolishly, and we are reminded and relieved that we get away with it when we watch the heroes of these stories fall.

But what of the character who snuffs out, who desecrates the hero? What of the executioner? The eye-slicer, the ear-cutter, the flayer, the flogger, the imperious king, the dictator, the jihadist, the torture artist? What of Laurence Olivier’s dentist in Marathon Man, the Nazi sadist? Ben Kingsley and Sigourney Weaver, taking turns inflicting pain in Roman Polanski’s Death and the Maiden? I do not feel purified by watching them; I feel stained.

Brutality is suffering inflicted for selfish gain, cruelty of a particularly human strain. Witnessing it in movies seems not catharsis but admonition: the veneer of civilization is thin.

I should know: I have hacked a man’s throat with a small, blunt knife and watched as his life gushed out. I have allowed the police to cart off my innocent young daughter, and then I have denounced her as she is tortured, her face pressed against a white hot iron. And often, sometimes nightly, I’ve had to run through the narrow streets of Montreal and Jerusalem, climbing up walls, out of windows, hiding behind dumpsters, I’ve had to run for my life from the oppressive state, from the minotaur, from my university painting instructor.

Carl Jung’s description of dream structure is not so different from Aristotelian dramatic principles or North American film script conventions: what Jung calls Exposition is our Act I, setting the stage with theme, character and place; Development is classic Act II, the playing out of conflict and action; Crisis is the Climax; Lysis is the resolution or conclusion, Act III. Filmmakers structure films in order to create emotional momentum, to keep us from getting bored. Jung structures dreams in order to read us.

Some neurobiologists think that dreams are rehearsals for survival, if we run from disaster in our sleep, we’re more likely to do it when awake. Freud stripped dreams down to a single, telling essence, be it conflict, neurosis or wish-fulfillment. Various cultures have seen dreams as prophecy, healing, or divine intervention. As all human bodies are variants of the same basic genome, so our psychologies simply play off a fundamental human psychology: Jungians read dreams as messages from this unconscious, collectively held and personally expressed.

Sharon is a tiny, blonde woman who dresses in pale silk and pearls. She speaks softly and is, as far as I can tell, fearless. I suspect that if she weren’t an analyst she would tame lions. Her talent and work, whether with adult neurotics or troubled kids, is to behold a psyche – that messy, alive, invisible thing – and to accept it, understand it, reflect it. To give it back to itself, nudge it toward wholeness. Her take on dreams is informed by Jung and also by decades of experience, of witnessing people thrash out meaning in their lives. She takes the internal narrative –dreams– as reflection both of the dreamer’s own psyche and the human consciousness we all share. Sharon translates, and transforms, nightmares: killing is repression; I am the killer, I am the innocent, my self is refracted in the violence of my dreams. The images are all clues.

Seeing our selves more clearly is a kind of spiritual proprioception. As these selves of ours are always caught in the sticky web of culture and history, seeing the web more clearly allows for more nimble navigation of it. If we can intelligently read our dreams, our own moving pictures, we are not bound to act blindly according to buried fears and desires.

Ditto, perhaps, for films. If we peer into the collective darkness, if we peel the text from the subtext of our cultures, might we be better off?

I am a filmmaker who no longer makes films: after a series of short films, my first feature was, despite a flurry of meetings with producers and a lovely actress in Montreal, never produced; it became a novel instead. While not explicitly violent, the work does explore how decent people (namely, a drifting actress) come to take morally questionable action, how our most altruistic motives can be twined with the most selfish. My husband has asked me why my characters aren’t better people; he doesn’t understand, and doesn’t like my need to traffic in what he sees as tawdry, what I see as human. He doesn’t like that my brain even comes up with this stuff. I don’t think I’m coming up with anything; I’m just watching, and trying to describe.

If we can see the ways in which we are wounded and the ways in which we wound, aren’t we more likely to be kind? If we can see the ways in which we are blind, isn’t our vision at least partially restored?

Too: the light in chiaroscuro works so well because the darkness is so thick. We are barbarians with moments of grace. Cruelty sometimes inspires resistance, transcendence.

I once wanted to make a movie based on Etty Hillesum’s An Interrupted Life, which is a compilation of letters and journals of her time during World War II. Photographs show a young woman with short, dark hair, bright eyes. She lived in Amsterdam, was a secular Jew, and wrote as a way to figure out her path in life. Living in a non-Jewish household, and consorting with the bohemian class, her writings limn the city in which she lives and her coming into her self, sex and her physical desires, the world of ideas opening to her. Politics and religion stayed in the margins until the Nazis invaded her life and her pages. She was recruited to the Jewish Council, where she performed administrative duties, but she hated this work and requested a transfer to Westerbork, a camp where she worked in the department for Social Welfare for People in Transit. These people were in transit to death camps. In time, and despite chances to escape, she became one of those sent. She accepted this fate. I came across, and was stunned, by her journals when I was 29, the same age as she was when she was gassed at Auschwitz.

Although unmade, scenes from this hypothetical film are cut into the montage that slow-burns at the back of my brain:

INT. WESTERBORK TRANSIT CAMP: She nurses the sick and comforts the anxious in the barracks. They all know what they’re waiting for. Etty tries to get a smile out of a fraught new mother. She can’t. The nursing infant unlatches from his mother’s breast. He gurgles, milk-drunk. The mother can’t stand it, she tries to contain herself. She hands the baby to Etty while she goes off to scream. Etty gentles the baby, coaxing him to sleep. Kisses the top of his little bald head.

INT. CATTLE CAR CROWDED WITH FAMILIES – DAY: Etty scrawls on a postcard. From outside, we see her fingers reaching through the slat, letting loose the card which flutters down and settles on the gravel ballast of the railroad,

INSERT POSTCARD: her last written words: We left the camp singing.

A common interpretation of this act is that Etty had achieved great spiritual maturity, going Christ-like to her death. I prefer to see it as a beautiful fuck you to brutality.

—Julie Trimingham

.

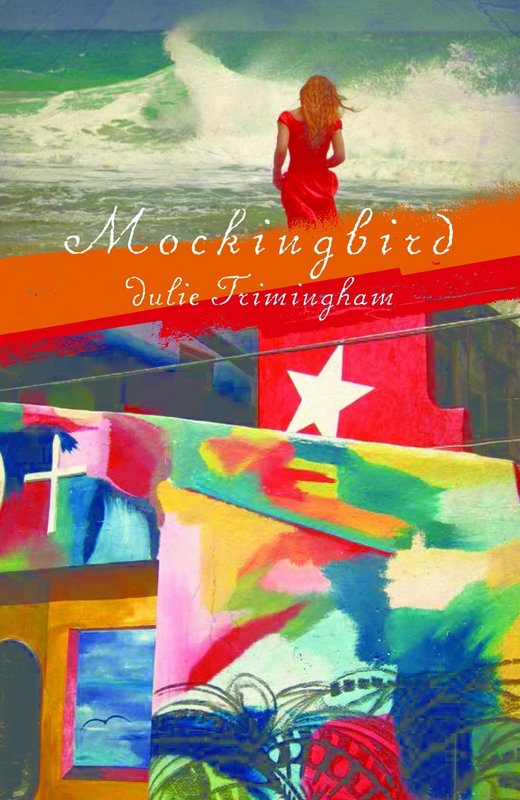

Julie Trimingham was born in Montreal and raised semi-nomadically. She trained as a painter at Yale University and as a director at the Canadian Film Centre in Toronto. Her film work has screened at festivals and been broadcast internationally, and has won or been nominated for a number of awards. Julie taught screenwriting at the Vancouver Film School for several years; she has since focused exclusively on writing fiction. Her online journal, Notes from Elsewhere, features reportage from places real and imagined. Her first novel, Mockingbird, was published in 2013.‘

Julie Trimingham was born in Montreal and raised semi-nomadically. She trained as a painter at Yale University and as a director at the Canadian Film Centre in Toronto. Her film work has screened at festivals and been broadcast internationally, and has won or been nominated for a number of awards. Julie taught screenwriting at the Vancouver Film School for several years; she has since focused exclusively on writing fiction. Her online journal, Notes from Elsewhere, features reportage from places real and imagined. Her first novel, Mockingbird, was published in 2013.‘

‘

.

.

Julie Trimingham was born in Montreal and raised semi-nomadically. She trained as a painter at Yale University and as a director at the

Julie Trimingham was born in Montreal and raised semi-nomadically. She trained as a painter at Yale University and as a director at the ![goldwing[1]](https://numerocinqmagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/10/goldwing1.jpg)