Artist Diane Burko photographing at Viedma Glacier

Artist Diane Burko photographing at Viedma Glacier

.

.

An individual has not started living until he can rise above

the narrow confines of his individualistic concerns

to the broader concerns of all humanity.

Martin Luther King Jr.

Nothing intrigues me more than the act of misremembering. Simultaneous misremembering? For this, I assume there must be a reason. So when I viewed a recent exhibition of Diane Burko’s work, Climate Contemporary: Artists respond to Climate Change, at the Lake George Arts Project, and was overwhelmed by her photographs, hung in a place to be viewed first when entering the gallery, I almost left the exhibit thinking there were none of her paintings in the exhibition. Looking at the list of works one last time before leaving, however, I was surprised to find that I was wrong and carefully turned back to view the show a second time, finding one painting in the mix. When I asked Diane if she had ever shown her photographs alone (without her paintings), she mentioned (in error) this LGAP show, among others.

Diane’s photographs lift the veil. They remove the distance between the viewer and the subject, as they take your breath away and send a shiver, physically and emotionally. Indeed, for the first moment I saw them, I thought they were printed on the inside of glass instead of paper, so luminous were they. Because of the textures, scale, and richness of these images, one feels as though they are at the site, hanging out of the plane or helicopter, ship, etc, with her. I believe this is crucial to her mission in conveying the urgency of climate change. When trying to convey a subject such as global warming to a generation accustomed to communicating with abbreviations while texting & tweeting, or with snapshots via Instagram & Pinterest, you need to drive home the point in a way no report, summit, or documentary can. It was immediate. It was accessible. It was high-impact. The seductive beauty of the images is a motivating factor for the viewer, the sugar with the medicine. To me, it seems no surprise that Diane’s life and work as an exhibiting fine art photographer evolved simultaneously alongside her life and work as an environmental advocate.

Spert Island, January 17, Archival Pigment Print, 30 x 30 inches, 2013, ©Diane Burko

Spert Island, January 17, Archival Pigment Print, 30 x 30 inches, 2013, ©Diane Burko

By the visual eloquence of her photographs (not to mention the fact that she has gone to such painstaking lengths to obtain thousands of these shots for her various projects and exhibitions: on site, as well as from agencies and individual scientists) she conveys great passion, which is also a definition of art.

To those who know me, it must seem natural that I’d have a preference for Diane’s photographs as a means of communication. While this essay is surely about Diane Burko, I feel it’s only fair to briefly offer full disclosure. I am a printmaker (mostly of monotypes) and a lyric poet. It is no surprise then, that I favor a medium that captures a moment in time. Moreover, part of what I do for a living involves work with mindfulness meditation, the practice of being in the present moment. However, in my history as a gallerist, I’ve never favored photographs, and as an art-lover, I never recall singling out an exhibition of photographs as must-see. Rather, I tend to respond strongly to drawing, abstract painting and of course, printmaking. Having said this, there are, indeed, many photographs and photographers that I have deeply respected and admired. I only learned after this interview that Diane considers her photographs a hybrid somewhere between printmaking and photography. It seems to me that she is a painterly photographer, which to me makes all the difference.

It is also notable that there are many art critics, and I’ll mention a few, who hold opinions in direct opposition to mine expressed above. Rebecca Smith, sculptor David Smith’s daughter, curated the Lake George Arts Project exhibit, interestingly including four of Diane’s large-scale photographs and only one painting. She then made this curious comment in the Albany Times Union newspaper:

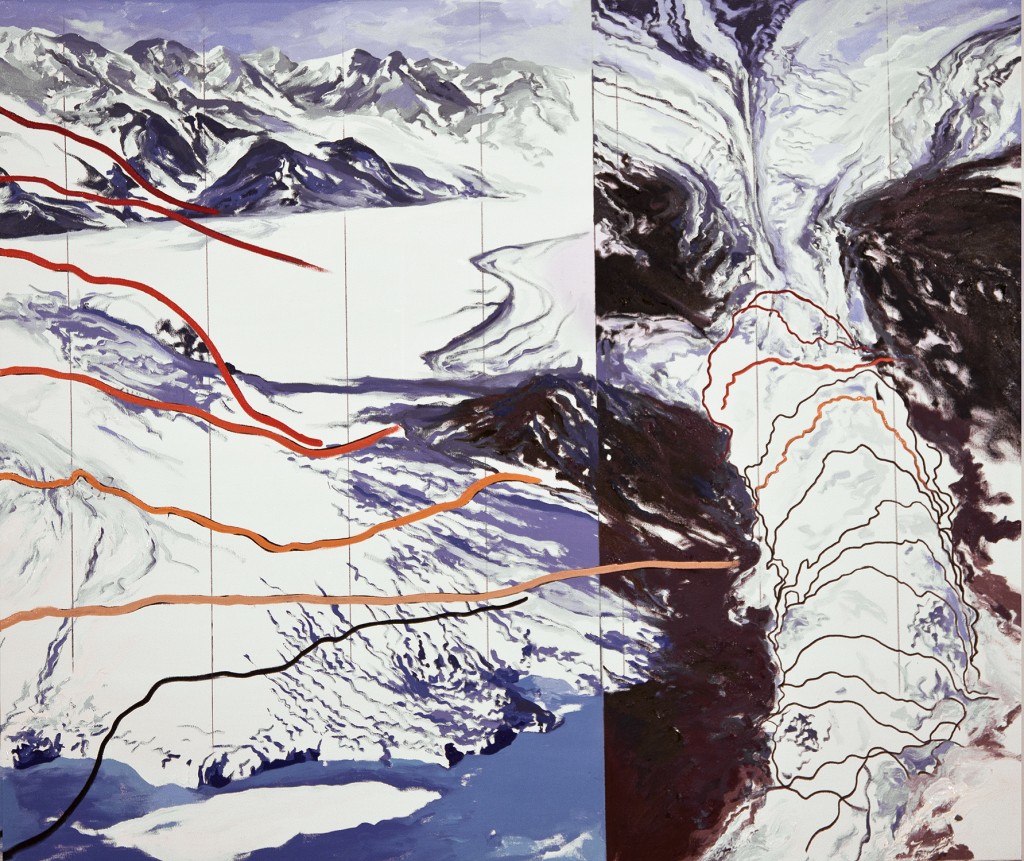

Burko, who began as a landscape painter, has a single painting in the show, which depicts frozen topographies threaded with variously colored lines. As the work’s title reveals, the lines mark the freak recession of the Columbia Glacier, located on Alaska’s southern coast, between 1980 and 2005. “I like to point out that this is how painting can tell you more than photography,” said Smith. “It is truer than a photograph, because you can put time into a painting. A photograph only captures a moment.”

Diane’s landscape paintings have been widely acclaimed and written about since the early 1970s. But things changed for her in 1977 when artist James Turrell (LINK — http://jamesturrell.com/) flew her over the Grand Canyon and Lake Powell in a refurbished Helio Courier airplane. Burko says the aerial views enabled her to abstract the landscape in new ways and that flying itself was thrilling. She began taking her own photographs to reference as source material for her paintings (often of monumental geologic phenomena) and to record her experiences. By 2000, her photography practice became another art form all its own.

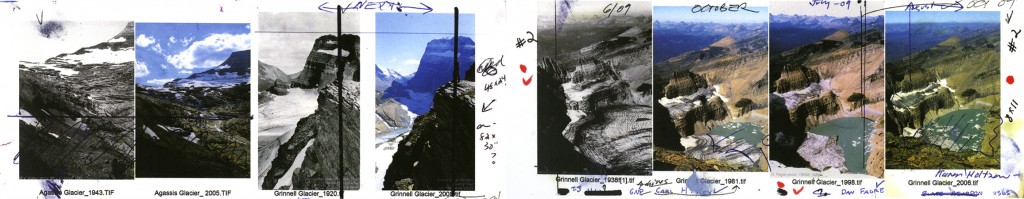

Notes from Politics of Snow. (Click for larger image.)

Notes from Politics of Snow. (Click for larger image.)

In her series Politics of Snow, shown in 2010 at the Locks Gallery in Philadelphia, Diane has drawn on the surface of a series of photographs, documenting, in plain visual language, environmental change. Not only does Diane document changes in the environment, she makes the viewer care. And when we care, we want to act.

A trip to Glacier National Park in 2011 became a turning point for Diane. The fact that at the turn of the century there were 150 glaciers there and fewer than 25 remain profoundly affected Diane. She’s quoted as saying she could no longer make beautiful paintings that did not have another purpose and … needed to exchange ideas with and collaborate with glacial geologists throughout the world. Diane became witness to a cause.

By 2013, opportunity allowed her to begin recording and reporting the unprecedented ice melt on our planet. In 2013 she sailed around Svalbard with 26 other artists, sponsored by an Arctic Circle Residency, and spent four days in Ny-Alesund with scientists from the Norwegian Polar Institute. In 2014, she returned North to Greenland’s Ilulissat and Eqi Sermia glaciers. In 2015 she made her second expedition to Antarctica and witnessed the Patagonian Ice Field of Argentina. Her current work reflects these Polar Antarctic and Arctic expeditions.

Most of us who have passed through the rigors of art school have had it drilled into us that painting from projected slides or source photographs can arguably “deaden” an image or at the very least take a scene “one-generation removed” for the viewer. In my opinion, skilled photography does not. There are gallerists and curators who prefer abstract art or paintings made en plein air for this reason, and given the luxury of time, such as her residencies at Giverny and Bellagio, Diane has made many plein air paintings as well. It is also important to mention that while many of Diane’s paintings begin from photographs, they soon depart in abstraction.

Reflets I and II (shown as diptych), Oil on Canvas, 84 x 60 inches each, 1990, ©Diane Burko

Reflets I and II (shown as diptych), Oil on Canvas, 84 x 60 inches each, 1990, ©Diane Burko

In an eloquent essay titled, Glaciers and climate change: narratives of ruined futures, (WIREs Clim Change 2015. doi: 10.1002/wcc.351), Geologist M. Jackson investigates various narratives in artistic, performative, cinematic, and other humanities-based representations of glacier-climate discourse. The author compares the metaphor of Diane’s melding of painting and photography to the merging of science and art that the work exemplifies. Furthermore, the article uses the same painting that Rebecca Smith described (Columbia Glacier Lines of Recession 1980-2005) and speaks of its usefulness in terms of a “fulfillment of prediction.” Jackson states, “By creating lines of current and estimated loss, Burko invites viewers to contemplate not the ice in current existence, but rather, where the ice not only once was, but also where the ice will not be.”

Jackson provides a solid argument worthy of consideration. And reconsidering Rebecca Smith’s curatorial viewpoint, perhaps she displayed Diane’s four photographs in a high-impact location, where they were viewed first in the gallery, and followed them with the one painting in the show to accomplish a “one-two punch” in the Lake George Arts Project exhibition. Playing devil’s advocate, would I have minded, however, if the painting were omitted from the exhibition? No. Would I love to have seen more of Diane’s photographs included in the exhibition? Definitely.

Columbia Glacier Lines of Recession 1980-2005, Oil on Canvas, 51 x 60 inches, 2011, ©Diane Burko

Columbia Glacier Lines of Recession 1980-2005, Oil on Canvas, 51 x 60 inches, 2011, ©Diane Burko

I also took a look at a recent article by Sue Spaid titled, Moving Viewers to Pay Attention, who set out to discuss how paintings, however mediated and/or distorted, complement ordinary perception in ways that photographs do not. While her thesis seemed to hold water, her discussion, for me, did not. I found myself readily able to substitute the word photograph for painting in many of her arguments. Here’s an example: By contrast, photographers who purposely direct spectators’ attentions risk undermining photography’s believability-advantage. Now re-read her remark instead with the word PAINTING substituted for photography. This was the case for me throughout her essay.

What bothered me most, however, and should have made me put down the Spaid article immediately, was when she accused anyone preferring photographs to be filled with “wishful thinking.” She went on to say: The plethora of die-hard photography fans and movie buffs undermines the notion of the human hand as necessarily commanding greater attention. “Photography fans” happily visit photography exhibitions and photo-fairs. A photographer surely uses a human hand. And a filmmaker? Hmmmm, last I checked Stieglitz & Spielberg were pretty human, and very commanding!

I believe by its very nature, painting is a lens through which the artist translates the viewed scene or object, this being part of its intrigue. In a documentary context, however, does “intrigue” seems less of a requirement? Is this is in part why the photographs play such an important role in Diane’s mission as an activist? Summarily, Diane has made sure by the quality of their “voice” that both her photographs and paintings be “heard.” I caught up with her recently to ask these and other important questions about her work.

MKJ: Your remarkable life thus far has evolved not unlike a Jenga Puzzle, no one piece being able to be removed at its exact time in your career. Your painter’s eye clearly informs your photographs, begging the question, how much so?

DB: I find that often people, when first confronting my 40 x 60” images, mistake them for paintings. I think my photography actually is located somewhere between photography and printmaking. The images are so not like Gursky, Ruff or Struth, and they are not a typical National Geographic highly detailed shot either. Rather there is a play between sharp and soft focus, distance and detail, atmosphere and color. The same issues I consider in my paintings.

MKJ: Are you a self-taught photographer?

DB: Yes. I think anyone out of art school learns to handle a camera. I first did with a Pentax to take slides of my work and, of course, then the world around me.

MKJ: Amongst other subjects, you’ve chosen two of the most difficult to photograph, ice and snow (because of the blinding whiteness and lack of contrast), in the most difficult of circumstances, frigid cold. Talk a bit about technique, how you’ve learned to obtain the gorgeous contrast, colors and textures in your images of glaciers, and the obstacles you’ve had to overcome technically.

DB: Getting there is the real challenge. As far as actual technique I am really a low-tech woman. I shoot with a Canon EOS 5 Mark II and Mark III, both with a 24-105 lens, as well as a Sony NEX VII – as simply as possible. No particular tricks. I try to stay at 100-ISO usually on Program and then adjust for aperture intermittently. Of course I am taking thousands of images. The process of editing is key to success. The challenge of the Polar Regions is of course keeping your batteries charged and your fingers warm.

MKJ: Do you manipulate your own photographic images on the computer in Photoshop or work with a designer to do this?

DB: I use Photoshop to crop. I prefer a square format or full frame. Basically I use Levels in Photoshop to adjust images. I try to keep the color as true to the experience as possible – no fancy manipulations.

MKJ: Remind us here about the paper, and printing process you employ.

DB: All prints prior to 2010 were printed on German Etching Hahnemuhle. Since 2010 I use Canson 100% Rag. The prints are made from an Epson 98 at a local facility, Silicon Graphics.

MKJ: I found an old quote of yours about your early photographic work describing the photos as “…trying to capture something I could never capture with painting… where the brush is not invited.” I believe that at the time you were referring to focal point or spatial concerns. However, does this statement still ring true for you?

DB: When a photograph says it all I don’t want to just copy it. I am not a super-realist. Rather it’s the bad photograph that captures an experience, a memory that then stimulates a painting idea. I am usually painting wet on wet, thus I welcome evidence of the brush mark. I value creating multiple distances for viewing a painting. When far from the canvas, one takes in the landscape, the total image. Yet as you get closer, the surface reveals many abstracted areas of paint, color, and surface texture.

MKJ: Have you ever shown your photographs alone, without your paintings, and/or would you consider this if you have not yet?

DB: Yes, I first did at the Locks Gallery in 2006, 2010 & 2011; the Philadelphia International Airport in 2007; and most recently in September 2014 at the LewAllen Galleries in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The show was titled, Diane Burko: Investigations of the Environment. A digital catalog of this show is available.

Also at this moment I have a number photographs on exhibit at the Noyes Museum in an exhibit titled, Frozen Earth: Images from the Arctic Circle. And I will be showing photographs exclusively at Kean University in an upcoming 2016 exhibition titled, Glacial Dimensions: Art and the Global Ice Melt Diane Burko and Paula Winokur.

And of course there were those four photographs that you saw at the Lake George Arts Project this summer in Climate Contemporary: Artists respond to Climate Change.

MKJ: Do you see your paintings as playing a secondary role and the photographs becoming stronger players as you become more and more active in speaking out to educate the world about climate change? Do you foresee a time when painting will become obsolete as a means of communication for you; or rather, is painting a passion that you will never abandon regardless of the role it does or doesn’t play in your life as an activist?

DB: Painting is such a compelling medium, so charged with emotional power in our virtual/digital worlds. Personally, I need to use both mediums. Sometimes one medium takes priority over the other. At other times I go back and forth. I have diptychs and quadtych paintings about climate change that I know are truly compelling. Right now I am experimenting in my painting studio with some abstractions based on Landsat images while also developing a major photo project. So both impulses are being satisfied alternatively.

Diane Burko’s Studio, Summer 2015

Diane Burko’s Studio, Summer 2015

MKJ: Your photographs document the passage of time and so can be used as a demonstrative tool, crucial to your mission. They also have a time stamp, leaving a record for scientists of the future. Can you speak about this legacy?

DB: Actually my photographs only document the time I am witnessing the glacier. But I am providing that record for other glaciologists to reference in the future, which makes me feel like I am making a contribution. This practice of visual comparison is called “repeat photography” and has been utilized ever since the invention of photography. Geologists rely on these visual records of change in the environment. They return to the same sites year after year (at the same time) to gather evidence of change. When I first began my Politics of Snow project, my paintings were based on their chronological repeats, sourced from USGS, NASA and the National Snow and Ice Data Center.

MKJ: Looking ahead, tell us about your upcoming agenda, including future travel plans and how these include your artwork, particularly your photography. Do you see any inventions or changes on the horizon involving your creativity?

DB: For the foreseeable future, that is the rest of 2015, I have no Polar plans. After so many trips over the past few years I need uninterrupted time to process all the information gathered in a deeper way. In my painting studio I am experimenting with new formats integrating maps as well as new painting techniques and materials. With my photographs I intend to create more grids of multiple images from the same locations, implying the passage of time. I am also exploring other conceptual strategies to create other metaphors about issues of climate change like my Deep Time pairings. Video is another avenue of exploration. I have footage from all of my expeditions that still needs to be reviewed and edited.

MKJ: What makes you most discouraged in regards to climate change?

DB: The fact that so many politicians engage in willful ignorance. The fact that doubt has been injected into the public discourse just as it was years ago with the harmful scientific proof about cigarettes and the ozone layer. How profit and greed seem to dominate everything is truly disheartening.

MKJ: What makes you most encouraged in regards to climate change?

DB: The fact that we are talking about it here; that more and more artists like me in multiple creative fields are dealing with this issue in their work; that the amount of coverage on climate change, droughts, forest fires, and extinctions are increasing in the press. And then there are politics. There are actually candidates running for the 2016 Office of President who are speaking to this issue. The fact that President Obama, along with the Pope, are calling attention to the perils of climate change – gives me hope.

MKJ: How can we get involved in affecting positive change at the local level vis-à-vis climate change?

DB: Each of us, aside from being mindful of our fossil fuel consumption, local food consumption and recycling, must be vocal. The personal is political. If each of us actually petitioned our representatives with our concern – often – it would make a difference. This issue impacts us all, and our grandchildren and their grandchildren as well. The time to act is now.

—Diane Burko & Mary Kathryn Jablonski

.

A gallerist in Saratoga Springs for over 15 years, visual artist & poet Mary Kathryn Jablonski is now an administrative director in holistic healthcare. She is author of the chapbook To the Husband I Have Not Yet Met, and her poems have appeared in numerous literary journals including the Beloit Poetry Journal, Blueline, Home Planet News, Salmagundi, and Slipstream, among others. Her artwork has been widely exhibited throughout the Northeast and is held in private and public collections.

Interesting meditation on photography and painting, both the intro and the interview. I was just reading Sontag On Photography recently and arguing with her in my head. The looking is the thing, I guess.

Thanks for your comment. Sontag is brilliant. I’d love to know what you were reading and will try to find it. I look forward to seeing more comments. This is fertile field for discussion — and certainly a timely one!

On Photography.

Yes, yes. Just marvelous. Thank you for bringing this to our attention. “Photographs really are experience captured, and the camera is the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood…Photographs furnish evidence.” I want to quote her every word. Here’s a link to an excerpt: http://www.susansontag.com/SusanSontag/books/onPhotographyExerpt.shtml

But she has some things to say that are more problematic, to me. Here are two of my blog posts about them:

https://marilynonaroll.wordpress.com/2015/08/04/see-what-im-saying/

https://marilynonaroll.wordpress.com/2015/08/17/look-at-me-dont-look-at-me/

I am inspired by your thought-provoking questions. Particularly those about the selfie, which I personally abhor (when we’re talking, yes, about a book full of them by a pop-culture star at point-blank range). Let’s not forget that Sontag had a relationship with Leibovitz, whose works IMHO, are the opposite in content of the selfie. Annie is able to pull deep, soul-filled portraits from her subjects. Then again, there’s Vivian Meyer, whose selfies I do not hate at all. Their mystery and depth intrigues me. No pun intended, but it’s not black & white, is it?

Your interview is a wonderful “way in” to the creative process, and an excellent introduction to Diane Burko’s art.

Thank you for your interest and comment, Judith. Diane’s photographs are breathtaking to view in person – and I think we can all agree, her passion is evident and her mission is crucial.