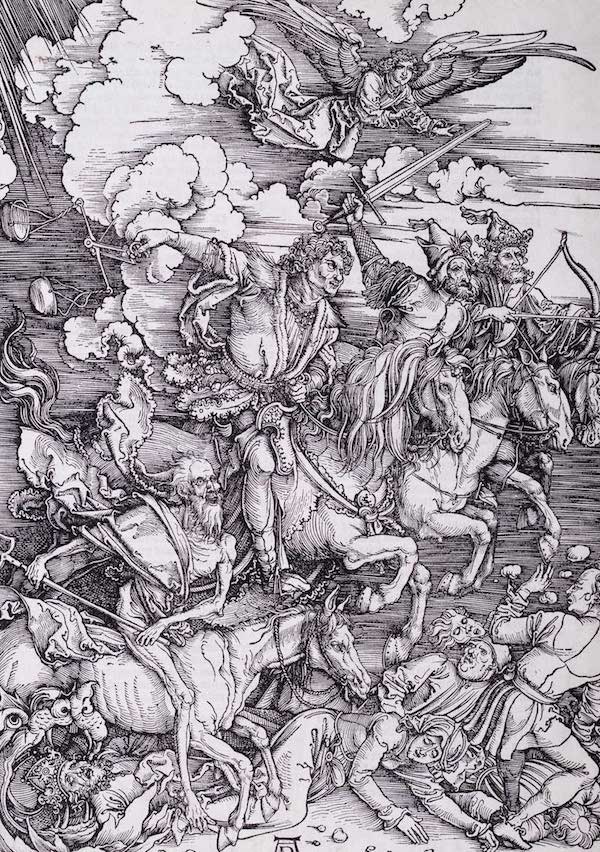

And I saw, and behold, a pale horse, and its rider’s name was Death, and Hades followed him; and they were given power over a fourth of the earth, to kill with sword and with famine and with pestilence and by wild beasts of the earth.

Revelation 6:8

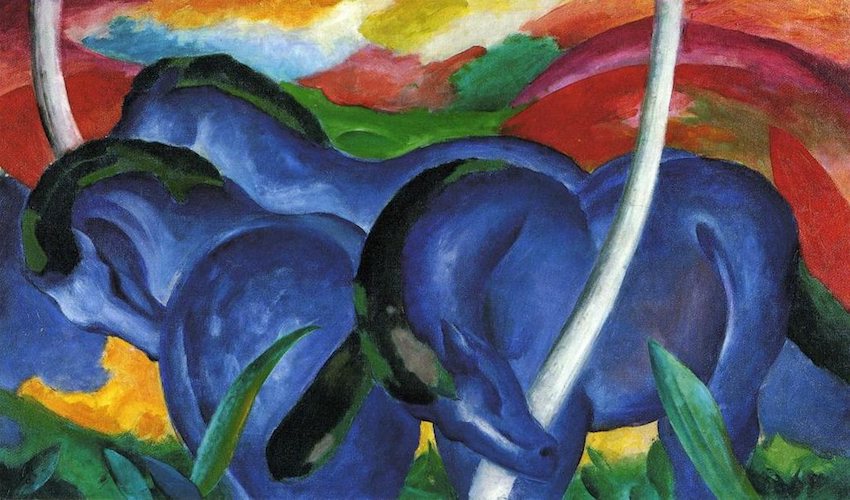

Franz Marc’s The Large Blue Horses—another work of art that has been with me almost my entire life, a print of which also has hung on a wall for some fifteen years, and I can’t remember when or where I first saw it. My best guess is in the library of elementary school, high up in childhood memory, among other paintings on the walls surrounding the low shelves that held books within reach of our hands and hearts and minds, appropriate for the course our lives were supposed to follow.

The blueness of the horses did not strike me as strange but rather was a given supported by the mass of their collective surge and the energy of the overall composition, their motion made significant by their self-possession, the color itself part of some larger motion I did not question and wouldn’t have grasped if explained. But what I took from it then, I think, is that there could be power in reflection and composure.

And the painting has survived the process of school, its ideas of itself, its upward gradations; and the rising flood of images that followed on screens and in popular print; and, when I studied art in college, the outline taught that put art on an ascending conveyor belt of movements. There is no such thing as progress in art or any permanence in our ideas and distractions.

Events from the last years and changes in my life and recent reading, however, have unsettled the painting and made me question its place now over my hearth.

Marc painted The Large Blue Horses in 1911, for many a time of alienation from and revolt against rapid industrial growth in Germany and the materialist Wilhelmine society it brought, when Nietzsche’s appeals for a return to Dionysian passions flourished, when crisis in the Balkans increased in pitch and European instabilities made global war seem inevitable, a war which many others found attractive, a world whose vast web of motives and intrigues most of us have forgotten, if we ever learned it.

What I’m supposed to say is that Marc was a German Expressionist, who looked not at the facts and impressions of people and nature and society but at subjective realities beneath the surface, at undercurrents of self and culture, and, hopefully, at something beyond and higher. The animals he painted represented human states and a desire to return to uncorrupted nature, nature expressed in ideal landscape. Marc created his own color symbolism, and blue stood for the male principle, serious and spiritual.

All these terms are as intriguing as they are slippery, ultimately meaningless.

Of course the painting is sexual, but that slant obscures as much as it makes clear.

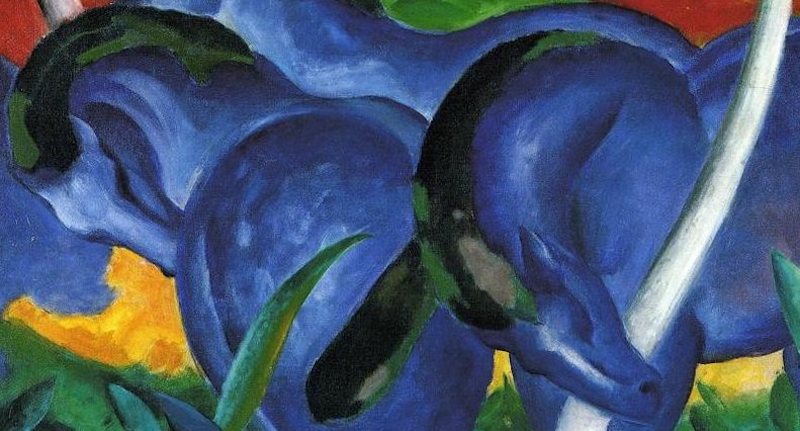

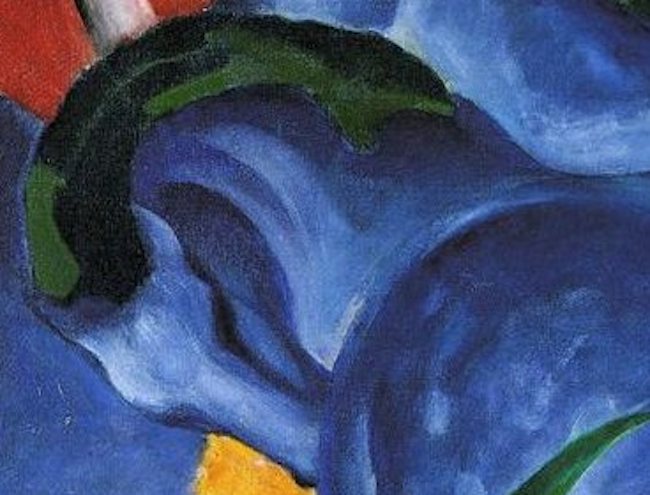

But there is no escaping the sensuous, sinuous, swelling flesh of the horses or the suggestive pull of their movement or the tension of the contrasting colors. The rhythm of their bodies continues into and complements that of the hills and sky, positing larger context. The horses’ blue, a color that optically recedes, is placed in front, while the distant hills are painted the forward red, this atmospheric reversal closing foreground and background and increasing the break from expectations, moving us from the nature we think we know.

Horses themselves give pause—such large animals that are not predators, that possess great strength yet are graceful and reserved. A horse without a rider lifts the burden of possession and use, opening up possibilities and raising questions. With their bowed heads Marc’s blue horses submit to the rhythm and yet push against, parting the distended white trees that divide the canvas.

In 1913, the world closer to war, Marc painted The Tower of Blue Horses, where there are four blue horses now, vertical and rising, open-eyed and agitated, their flesh taking on the angles of Cubism.

A few months later, war still closer, in Fate of the Animals the horses, frenzied and in peril, turn green, blue mixed with yellow, which, Marc tells us, “cannot still the brutality of red,”

in a picture that takes animals and landscape to the point of annihilation by the slashing diagonal lines, red flames, that dominate the canvas and set the fractured composition. An irony here—the painting was actually damaged in a fire and Paul Klee only partially restored the area on the right.

Fate of the Animals recalls Picasso’s Guernica, another painting of wholesale destruction and disruptive composition, his response to Franco’s request to bomb the town, Germany’s tuneup for the next world war. Both have since stood as pictures of the horrors of war in general, of civilization on the brink.

Marc also shows the influence of the dynamism of Futurism, though with inverted intent; Picasso continues his cubist experiments in his synthetic phase, with clearer representation in his angled shapes. These maneuvers are not advances, however, but adjustments to match the subject. But the breakup and rearrangement of parts does not create chaos but rather gives coherence to disorder, and with coherence, the terror of beauty.

Most have taken the bull as the source of the massacre, representing fascist brutality, and the horse stands for the slain innocents, their agony and death. The bull alone is passive, however, with a stilled face that is hard to read, and Picasso used the figure for other representations, including of himself. Guernica is direct in its images and but ambiguous in its meanings, leaving unanswered questions. The bull also leads us to the Minotaur and the labyrinth of mythical meaning. Still, there is the overpowering sense of revulsion at something we have done to ourselves.

But in Fate of the Animals the source of destruction is external, coming from some unseen force above, beyond our agency, entering the canvas in the flames at the upper left and rebounding and continuing their destructive course across the picture plane. It is, in fact, a picture of apocalypse. Frederick Levine, in The Apocalyptic Vision, makes a convincing case, explaining how Marc drew cataclysm from Wagner, from Nordic myth. The long column that slants left against the flames is Yggdrasil, the eternal ash, which shelters the four willowy deer on the right, who alone will survive to start a new race. Apocalypse is not just inevitable, it is desired.

We know that everything can be destroyed if the germination of a spiritual race does not endure the test of the greed and impurity of the masses. We struggle for pure ideas, for a world in which pure ideas can be thought and can be expressed without becoming impure.

Marc saw the war as the coming apocalypse and volunteered early, before conscription. It was something he had to witness and endure. But the imagined glory of the past that others wanted restored was what he wished to see destroyed. Like them, he had no idea what was to follow.

The combat of the infantrymen which I witnessed yesterday was incredibly hideous, more horrifying than anything I have ever seen. I was totally shaken last night. The courage with which they advance, and the indifference, indeed, the enthusiasm for death and for wounds has something mystical about it. Naturally, it is a mood of reconciliation, the clarification of something that was previously uncertain.

Purity is a trap, a dead end, and this is pathology. Marc, who was given to bouts of depression, has surrendered to his mood and in self-immolation projected it into unnamed abstraction. Spiritual shell shock here as well, as the pathology of the self meets the pathology of the world in a landscape of death and shattered mirrors.

And the apocalypse of Fate is what The Large Blue Horses leads up to, what stirs the trio in their lowered gaze above my mantle. Reading Levine forced reexamination of the painting and led me in downward spiral. My living room deadened in its plane and turned into a no man’s land, a grayness spreading to lifeless winter trees outside my windows, to lifeless streets, and lifelessness beyond, endlessly. Everywhere I went I saw entrenched lives and, on faces, in reports from around the world, the signs of dissolution and breakage. I avoided looking at the painting, then started avoiding the room. I long debated taking it down, not finding resolve.

Nietzsche’s descent into madness, legend goes, began with the sight of a beaten horse.

But psychology is sterile reduction. And to reject myth as superstition is to deny its power and persistence. Some notion of apocalypse has been with us a long time. It may be one of our earliest formations. In Dürer’s gorgeous woodcut the four horses unleashed in Revelation take the riders who scourge the land, necessary preparation for a new heaven and new earth. Destruction precedes renewal—or is it merely the underside of our highest, purist aspirations?

It is impossible to recreate the confusion of thought and emotion of Marc’s time and get a fix, but it is just as impossible to gain footing now in a world certain only of itself, not going anywhere at breakneck speed, where wars are fought by others and victims most often are others and apocalypse has become a casual diversion in movies and video games.

Too often when we read biography into art we only read ourselves. What I most became aware of looking at the Blue Horses was myself, a depression that came from within and radiated out. The signs of breakage were still there outside my windows, however. They are still there. They have always been there. If I hadn’t noticed them before it was because I wasn’t looking.

And I don’t know if a glance towards apocalypse isn’t what drew me to the painting over fifty years ago.

Only by risking everything do we know what anything is worth.

Or:

We risk everything because we do not know what else to do.

I have no idea which is true, if either.

I only know the old man will always be with us.

And that if I take the Blue Horses down I will be lost.

Slowly, cautiously, I have returned to their coiling, inward gaze. Color has returned to the room, slowly, cautiously, and leaves have returned to trees, and grasses return to barren fields and softly fill furrows and cover mounds though from which chunks of old concrete still protrude, though a grayish mist lingers over all.

March 4, 1916, near Verdun, Lieutenant Franz Marc rode a chestnut bay out on a reconnaissance mission and did not return. He was killed by shrapnel, French or German, no one knew. Another irony. The world is littered with ironies.

.