The waning moon and a streetlight offered to help when I lost the silver pendant of my necklace walking my puppy in the early morning twilight. But after a moment’s search I let it hide, something precious and intimate concealed, and now it endears that part of the neighborhood to me, as W.S. Merwin’s The Moon Before Morning does with every poem. —A. Anupama

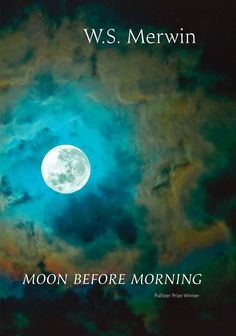

The Moon Before Morning

W.S. Merwin

Copper Canyon Press

120 pages, $24

ISBN: 978-1-55659-453-3

.

The waning moon and a streetlight offered to help when I lost the silver pendant of my necklace walking my puppy in the early morning twilight. But after a moment’s search I let it hide, something precious and intimate concealed, and now it endears that part of the neighborhood to me, as W.S. Merwin’s The Moon Before Morning does with every poem.

On one of the many double-dog-eared pages in my copy, in the poem “How it happens,” the sky speaks:

The sky said I am watching

to see what you

can make out of nothing…

This poem appears in the last of the four sections of the collection and is followed by the poet’s ars poetica, “The wonder of the imperfect.”

Nothing that I do is finished

so I keep returning to it

lured by the notion that I long

to see the whole of it at last…

§

W. S. Merwin is prolific and draped with honors. His last book of poetry, Shadow of Sirius, won him his second Pulitzer Prize. He has served as U.S. Poet Laureate (also) twice (1999-2000 and 2010-2011). He was born in 1927 in New York City but grew up in New Jersey and Pennsylvania. His influences are deep and personal. His father was a Presbyterian minister; he knew John Berryman and R.P. Blackmur at Princeton; Robert Graves’s son Merwin was his tutor for time. Now he lives with is wife Paula in Hawaii, on a 19-acre palm forest, which he planted from seed. Earlier this fall, the Merwin Conservancy announced permanent protection for the forest, in cooperation with the Hawaiian Islands Land Trust.

Merwin’s new collection begins with a scene in this forest garden in a poem called “Homecoming.”

I looked across the garden at evening

Paula was still weeding

The poem is typically (for Merwin) unpunctuated. The assonance and half-rhyme between “evening” and “weeding” fold the lines together, suggesting the core thematic structure: couple and place.

Likewise, in “Theft of morning,” the beautifully described (anapests — “to the sound” — accented with alliteration and internal rhyme) palm garden grounds the meditation.

Early morning in cloud light

to the sound of the last

of the rain at daybreak dripping

from the tips of the fronds

into the summer day

I watch palm flowers open

pink coral in midair

among pleated cloud-green fans

as I sit for a while after breakfast

reading a few pages

with a shadowing sense

that I am stealing the moment

from something else

that I ought to be doing

so the pleasure of stealing is part of it

§

Stealing moments is a theme of age. In the sonnet “Young man picking flowers” the poet delights in twisting up time and age to nullify their effects. Beginning here:

All at once he is no longer

young with his handful of flowers

in the bright morning…

and then ending:

the cool dew runs from them onto

his hand at this hour of their lives

is it the hand of the young man

who found them only this morning

The couplet’s question becomes almost a non-question because of the absence of question mark and because of Merwin’s precise tightening of line and thought by the repeated words (“hand,” “them,” and “morning”). Notice that the man is “young man” at the end.

In “Beginners,” time and memory hold hands for a moment and explain the game.

As though it had always been forbidden to remember

each of us grew up

knowing nothing about the beginning

but in time there came from that forgetting

names representing a truth of their own

and we went on repeating them

After this running start in rhymes (“nothing,” “beginning,” “forgetting,” “representing,” “repeating”), he goes on repeating variations of forgetting and remembering until “the day we wake to is our own.”

§

Merwin repeats the word “frond” frequently in the first section of this collection, anchoring us firmly in that garden home. It appears first in “Theft of morning,” and then recurs in several other poems, often aligned with time of day (to be precise, of course, for the garden changes with the light and weather). “White-eye” starts: “In the first daylight one slender frond trembles / and without seeing you I know you are there…” In the poem “From the gray legends,” “the screen of fronds” appears “before daylight,” and then in the poem “One day moth” he starts this way:

The lingering late-afternoon light of autumn

waves long wands through the arches

of fronds that meet over the lane

A poem titled “High fronds” gives us the image from a distance:

After sundown the crowns

of the tallest palms

stand out against

the clear glass of the eastern sky

that have no shadows

and no memory

the wind has gone its own way

nothing is missing

In “Garden notes,” the repetition summarizes itself at its zenith, encompassing all times of day and night:

All day in the garden

and at night when I wake to it

at its moment I hear a sound

sometimes little more than a whisper

of something falling

arriving

fallen

a seed in its early age

or a great frond formed

of its high days and nights…

“A breeze at noon” brings the repetition of “frond” to a close when the moment

drops a dead Pinanga frond

like an arrow at my feet

and I look up into the green

cluster of stems and gold strings

beaded with bloodred seeds

each of them holding tomorrow

and when I look

the breeze has gone

The word “frond” shares doubled consonance with “friend,” which Merwin repeats in the poem “Footholds.” The lines, specific in their setting of time and place, favor memory over forgetting.

…Father and Mother friend upon friend

what I remember of them now

footholds on the slope

in the silent valley of this morning

Wednesday with few clouds and an east wind.

§

The word “echo” takes over as a primary repetitive motif in the second section of the collection and beyond. Again, the repetitions shift in their references, beginning with “Another to Echo,” which offers praise to Echo, the famous nymph in Ovid’s The Metamorphoses who could only repeat the last words of others, and who loved Narcissus in vain.

you incomparable one

for whom the waters fall

and the winds search

and the words were made

listening

Later, in “Garden music,” the echo as sound and echo as memory of sound coalesce.

In the garden house

the digging fork and the spade

hanging side by side on their nails

play a few notes I remember

that echo many years

as the breeze comes in with me…

And in “Variations on a theme,” the penultimate poem in the collection, Merwin personifies memory in the line “thank you for friends and long echoes of them”.

§

In an interview with Bill Moyers shortly after The Shadow of Sirius was published, Merwin mentioned having been pleased and encouraged to hear that children had no trouble understanding his poetry. To test this, I chose a few poems from this collection to share with my five-year-old daughter. I picked “The palaces” for its clouds like “gray cliffs / icebergs in other lives” and for words like “white-knuckled,” “pocket” and “crag.” My daughter wanted more. She asked, “What comes after that?” And so I continued with “Old plum tree” and “Old breadhouse,” which won her approval, too.

Reading the poems aloud confirmed another of Merwin’s comments in that interview: that poetry relies heavily on the sense of hearing. The poems are full of sounds — the dripping leaves, the whisper of things falling in the night, those echoes, real and figurative. However, his use of “frond” seemed to me particularly visual. I remembered learning that the filtering of light through fronds and other kinds of leaves can even act like pinhole cameras, projecting images of the sun or moon across the ground, a fact I once used for watching a solar eclipse. But Merwin turns the strong visual aspects back to sound.

In “Lear’s wife,” the speaker says twice “I looked at the world” (visual). But the poem’s hinges are fastened to “if he had listened to me / it would have been / another story” and “only Cordelia / did not forget / anything / but when asked she said / nothing” (auditory). In “Another to Echo,” Merwin begins “How beautiful you must be / to have been able to lead me / this far with only / the sound of your going away” (visual metamorphoses to auditory). In “From the gray legends,” the color and texture of Arachne’s weaving opens the poem and carries its thread through to the end, all reflected in the strong visual of Minerva’s gray eyes. The only sound here, “all night her own bird answered only / Who”, is another uppercase exception to Merwin’s usual punctuation rules.

§

The silvery language hidden in plain sight on these pages only awaits a little breath of reading to reveal the pure way that dawn itself listens.

—A. Anupama

A. Anupama is a U.S.-born, Indian-American poet and translator whose work has appeared in several literary publications, including The Bitter Oleander, Monkeybicycle, Fourteen Hills, and decomP magazinE. She received her MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2012. She currently lives and writes in the Hudson River valley of New York, where she blogs about poetic inspiration at seranam.com.

.

.

“Hidden in plain sight,” a language that is, as Augustine found the scriptures to be, at once simple and of unfathomable depths. Something like water, like reflections or sky, but always touched with the human intelligence. Those are important observations about memory, which must always be reckoned with its corollary, forgetting. But, I wonder, why do “time and memory hold hands” only momentarily? Are they not intrinsically bound up with one another, or, rather, might not memory be time seeking, looking into, and reflecting itself?