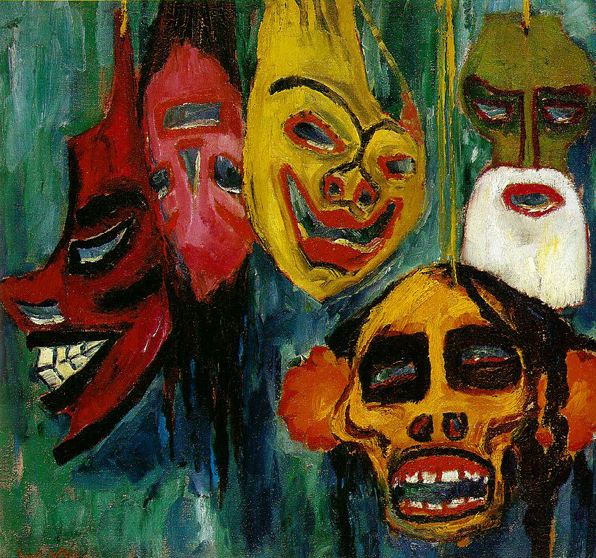

Emil Nolde, Masks (still life III), 1911. Nolde was a member of Die Brücke, a group of German “wild” Expressionists.

Emil Nolde, Masks (still life III), 1911. Nolde was a member of Die Brücke, a group of German “wild” Expressionists.

.

Because they couldn’t help but find what they were looking for, it might not be too far-fetched to imagine that the Modernists, when they opened up the passage into other realms and encountered the artifacts and spiritualities of the people they designated as primitive, were actually encountering nothing but their own subconscious minds — seen through the protective veil of the other. —Genese Grill

.

Imagine if you can the young European or American Modernists of 1918, just free of a violent and dreadful war waged by what they perceived as the forces and interests of their parents’ generation, but fought by their peers; the young Modernists, still reeling from their near escape from the close and darkly chaperoned drawing rooms of propriety, good taste, and claustrophobically monitored social morality, encountering a band of gypsies trundling along a London street with wagon, tambourines, loosened hair; or an exhibition of African masks and an anthropological explanation of magic and ritual; or the art of a schizophrenic, the art of children. They are aware of the new findings of psychology, and even sexology; but they have been schooled on positivism and the great God of Reason; they are about to pull back the curtains and open the windows to look outside of their sheltered worlds—but also to look inside, underneath, to peer into the dark abyss of their subconscious minds. They will find, that after centuries of good behavior and composure it may be easier, initially, to face their demons by looking through the mind, through the mask, of the exotic other. While their visions of their chosen “others” may often reveal their own socially-constructed judgments and assumptions about the varied peoples they simultaneously celebrated and condescended to, here I am not interested in correcting or revising Modernist ideas about these cultures, but rather with delineating a few central points of contact where innovations in twentieth century art and literature seem directly related to the era’s fascination with what it defined— for better or for worse— as primitive.

These areas, all of which are linked in some way to the development of abstraction and symbolism and an emphasis on Form in Modernist aesthetics, may be briefly mapped as follows:

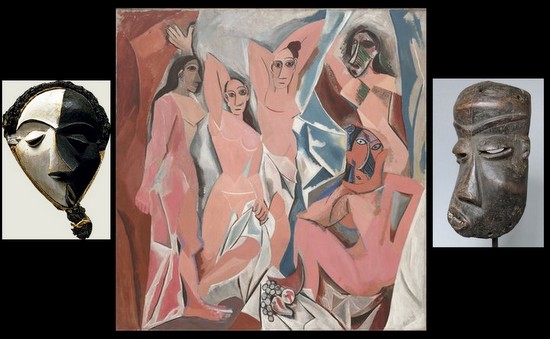

1. The idea of the primitive provided modernists with a model of making art wherein the Form, Gestalt, or shape of the abstracted image was thought to effect the physical nature of reality —thus abstraction and symbolism are related to what Freud in his Totem and Taboo called “the omnipotence of thought”.{{1}}[[1]]Freud, Sigmund. Totem and Taboo: Resemblances between the Psychic Lives of Savages and Neurotics. Translated by A. A. Brill. London: Routledge, 1919,149.[[1]] Picasso summed this idea up after viewing the African masks in the Trocadero in Paris in 1907 (the same year he painted “Les Demoiselles d’Avignon”), exclaiming: “Men had made these masks and other objects for a sacred purpose, a magic purpose. I realized that this was what painting was all about. Painting isn’t an aesthetic operation; it’s a form of magic designed as a mediation between this strange hostile world and us, a way of seizing power by giving form to our terrors as well as our desires”.{{2}}[[2]]Mallen, Enrique. “Stealing Beauty.” Guardian Unlimited: On-line Picasso Project. Web, 2006.[[2]] Even if most people did not believe literally that art changed the physical nature of the world, respectable science (Ernst Mach and the Empiricists/ extreme Positivists) and cutting-edge philosophy (Wittgenstein) themselves offered enough conflicting and confusing analyses about the nature of reality and the individual’s role in perceiving and constructing it to reasonably justify a species of such belief.

Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and Pende sickness masks

Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon (1907) and Pende sickness masks

2. Primitivism provided a model of creation whereby the ineffable, the emotional and subjective — rather than the literal, didactic, or rationally comprehensible—was the subject, goal, and essential experience of both art making and art perceiving. Primitivism joined forces with the new subjective science of psychology to deflect energy towards the inner and away from the outer as part of a Post WWI culture involved in a general resistance and rebellion against civilization (and its discontents) — against the rationalism, propriety, scientific positivism, and materialistic progress ideal which had sent countless soldiers home from the front maimed and haunted by nightmares. Insofar as the fascination with the so-called “primitive” was a critique of civilized rationality, it was also connected with the study of the minds and artworks of the insane and of children— and, by association, the study of the psychology of women (as the irrational, the hysterical, the mystical other within).

3. Primitivism seemed to provide evidence for universal archetypes — this last is rather complex, because the early twentieth century struggled with tensions between the individual and his or her loss of self in communal mass consciousness. Primitivism, furthermore, can be both progressive and reactionary, both internationalist and nationalist. The Nazis celebrated nationalistic folk primitivism, propagandizing for the values of simplicity, Germanic homeliness, and country life, against modernization, metropolis, and the mixing of races, but decried the “primitivist” tendencies of modernist art—distortion, ugliness, crudity, sexuality— which borrowed its techniques and subject matter from the art of non-Germanic peoples. Moreover, while individualism (as materialist isolation or as nationalism) may have been seen as anathema to the new collectivist visions of socialisms, communisms, archetypal psychology, or an internationalist art movement; the devastating effects of early 20th century mass hysteria, crowd violence, and blind obedience were also seriously problematic. While I will not explore the political dimensions of this last connection directly, they are, I believe, an important part of the atmosphere of the times, and most essentially demonstrate the complicated relationship between the drive for irrational mass ecstasy and the beneficial uses of individual critical rationality.

In terms of Art, the question of universality is central to abstraction and symbolism, as the Modernist often seems to assume that powerful abstract shapes or symbols, unintelligible sound poems, or irrational dream-images are connected to a subconscious arousal of some ancient primal truth, accessible across cultures and times, provided the artist or viewer free herself from the artificial trappings of civilization, science, and rationality.

To reiterate: three contact points between Modernism and Primitivism—all relating in some way to symbolism and abstraction — may be characterized as: 1. The concept that Form could magically effect reality; 2. The attempt to express the unutterable, subjective experience of emotion, and 3. The Search for a primal universal language.

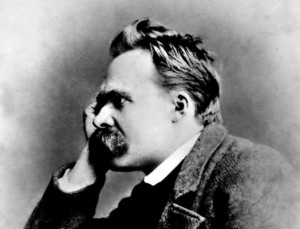

When speaking of Modernism and the Avant-garde, we are talking about a wide range of twentieth century European and American notions about contemporary consciousness, many of which —despite their connections to sophisticated, modern sciences like anthropology, psychology, sense perception, or physics —were engaged in re-mapping and, to a great extent, transgressing the traditional 19th century trappings of civilized society. In 1872, Friedrich Nietzsche had already undermined the edifice of civilized rationality in his Birth of Tragedy, introducing a new reading of Ancient Greece which would counter the prevailing picture of individuated order, balance, and harmony synthesized by the 18th century Art historian Winckelmann’s formula, “Noble Simplicity and Quiet Grandeur”. While Nietzsche’s theory of ancient Greek culture (an early form of primitivism) exposed the wild churning of the unconscious drives and the energy of dis-individuated drunken dancing, it also pointed to the terrifying desires lurking beneath even the most civilized Victorian exterior. This was an exposure which Sigmund Freud was quick to continue, pulling the proper masks away from the carefully composed psyches of his bourgeois patients, uncovering incest, death wishes, and other previously unmentionable perversions. This social and psychological unmasking becomes part and parcel of Modernism and its more radical sister—the Avant-garde—, as Art grew into another means to rip away facades; to disturb; to not only disorient the senses, but to scandalize the stolid satisfaction of the progress philistine. Art was to encourage its readers and its viewers to look at their own and their society’s demons, and to enjoin them (in the words of Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo”): “You must change your life”.

Modernism was a movement which concerned itself primarily with the subjective nature of reality, and thus with the creation of a non-linear discourse based more in symbol and metaphor than in narrative or sequential logic. Modernism, in its many manifestations — vorticicism, imagism, expressionism, surrealism, cubism, fauvism, stream-of-consciousness or the pre-logical, with dreams and other subconscious emanations, was — either as cause or effect of these tendencies, a movement engaged in vivifying a tired, possibly discredited language and artistic vocabulary through experimentation with forms and content. Frank Kermode, in his essay, Modernism, Postmodernism, and Explanation, characterizes Modernism and its avant-garde as movements characterized by a celebration of the illogical which eschewed explanation and its logical strategies in favor of the inexplicit. According to this theory, the modernists saw in the primitive, “a model of that which is not discursive, explanatory, that which baffles us by its isolation, its manifest inexplicitness, its apparent indifference to our concerns, its masks —in short, by its possession of an indistinct power that seems alien but that calls on us—with an urgency[…]to interpret it in such a way that we may discover the significance that we sense it must have, namely, the unutterable contained in it, which it does not attempt to utter”(365).{{3}}[[3]]Kermode, Frank. “Modernism, Postmodernism, and Explanation.” In Prehistories of the Future: The Primitivist Project and the Culture of Modernism, edited by Elazar Barkan. Stanford, CA: Stanford UP, 1995, 357-374.[[3]]

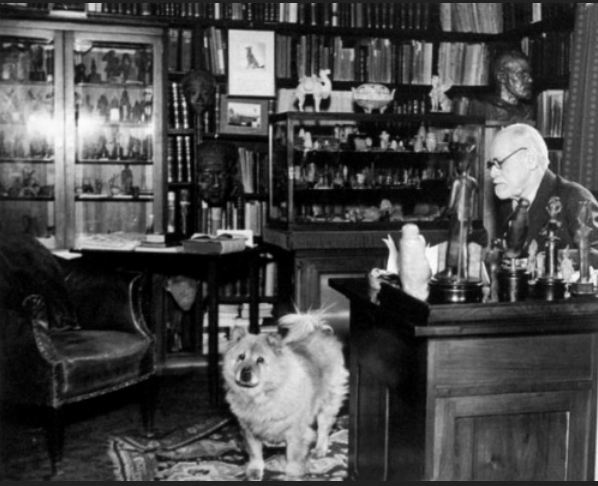

Freud in his study; look carefully and you can see the African mask in front of the book case.

Freud in his study; look carefully and you can see the African mask in front of the book case.

Freud’s 1913 Totem and Taboo—acultural product half-way between Victorian scientific positivism and Modernism’s celebration of the subjective irrational —interpreted what he deemed explanations for the savage’s incest dread, his totemism, and his obsessive compulsive behavior, utilizing these to create a system of logical speculation whereby his contemporary neurotic patients could be analyzed. While the Modernist would abandon Freud’s need to justify his fascinations as a somewhat rational system, Freud’s comparisons were important reflections of the Modernist project, suggesting that modern man was not only interested in the primitive, in African masks, and Oceanic figurines, as he would be in the scribble scrabble of his underdeveloped younger sibling, but also as manifest exterior images of what Kermode calls modern man’s own “internal foreign territory” (Kermode 365).

Perhaps the most important thing to remember about Modernism and its surprising interest in “Primitivisms” is that art had, by the turn of the last century, slightly different purposes than it had formerly professed—but these purposes had always been at least one side of art’s aims. If the history of Art can be distilled down to a battle between the Platonic Ideal of Harmonious Goodness and Aristotle’s theory of tragedy, Modernism took a distinct turn towards the Aristotelian model, requiring of Art that it be psychologically cathartic, emotional and transformative, which often meant that it would depict disturbing subject matter by way of discordant and ugly form. Despite varying degrees of emotional expressiveness or attention to aesthetic questions, pre-twentieth century audiences, theorists and critics had more often veered towards the Platonic concept of Art as a means to teaching morals; this was done mainly through mimesis — that is, representations of external physical reality— and by telling stories, usually ones wherein virtue was rewarded and evil punished. For the many critics who did not ascribe to the Aristotelian conception of Tragedy, Art was expected to be beautiful—in the sense of harmonious, whole, pleasing, and peaceful to look at—it was not to be anything but soothing, uplifting, or heroic. Within this stream of thinking, there were two goals as well, defined in the classical age by Horace as “to instruct and to delight”. The Romantics had only gone so far in breaking down these categories, by exploring sentiment, melancholy, and passion; and 19th century Naturalism, while engaged in depicting the more sordid sides of life, such as dirty feet, alcoholism, and prostitution — despite its possibly radical shift in subject matter and class consciousness — was still concerned with teaching morality, and still depicted narratives or tableaux vivantes in more or less traditional realistic styles.

In contrast, Modernism focused mainly on Form — and away from content or easily decipherable messages — in an attempt to express the internal experience of the individual, an experience made up of shifting psychological states which could often only be depicted by dissonance and ugliness. The modernist artist was faced with the challenge of how to communicate these internal states, these private languages, in such a way that they would be meaningful to someone who wasn’t inside his or her own head. The development of abstraction, as an emphasis on non-mimetic form which expressed the inner image of the individual’s emotions in a way that didactic, linear representation or narrative could not, is linked to this new purpose of art. In their search for a means to depict such pre-logical consciousness, the Modernist turned, naturally, to the primitive, because its artifacts, despite the fact that one could not presume to understand them in any logical way, were —or so the Modernist party line went —moving.

Of course all great art has always contained the formal elements which the modernist artist explicitly aimed to foreground; considerations such as composition, rhythm, the spaces between words and shapes, the sound of words, the mysteries of syntactic impact, the effect of dramatic placement, suspense, Aristotle’s “reversal” and “recognition”. The difference in Modernism was that these formal elements were now no longer simply tools to better convey a message, but became, rather, the essential material and even subject matter of the work of art. Gestalt— born of a new psychology that studied the powerful effect of shapes and arrangements — was considered the best means to express the shapeless unutterable stirrings of the psyche.

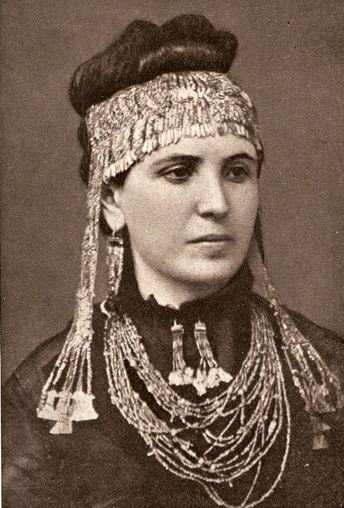

Heinrich Schliemann’s wife wearing what he called the “Jewels of Helen” excavated in what he thought was Homer’s Troy. (Photograph taken ca. 1874.) via Wikipedia

Heinrich Schliemann’s wife wearing what he called the “Jewels of Helen” excavated in what he thought was Homer’s Troy. (Photograph taken ca. 1874.) via Wikipedia

Although it would be nearly impossible to ascertain just what elements in history, culture, invention, or creation made the shift into Modernism possible, Hugh Kenner, in his The Pound Era,{{4}}[[4]]Kenner, Hugh. The Pound Era. Berkeley: U of California P, 1973.[[4]] mentions two earthshaking discoveries in the field of Archaeology/Anthropology, which he links to the development of Modernism: the discovery of cave paintings in the South of France in the 1890’s and the discovery of the artifacts of Troy. “Since about 1870,” he writes, “men had held in their hands the actual objects Homer’s sounding words name. A pin, a cup, which you can handle like a safety pin tends to resist being archaized. Another [cause] which may one day seem the seminal force in modern art history, was the spreading news that painted animals of great size and indisputable vigor of line could be seen on the walls of caves which no one had entered for 25,000 years…By 1895,” he continues, “….a wholly new kind of visual experience confronted whoever cared. The shock of that new experience caused much change, we cannot say how much; we may take it as an emblem for the change that followed it” (29). Further, he tells us, the discovery and gradual decipherment of fragments of the Greek poetess Sappho’s verses, from 1896–1909, provided the Modernists with a powerful model of concision, spareness of words, and fragmentary beauty; since the papyrii were miserably crumbled, all that existed were phrases and, in some instances, single words–and these small gems were wondered over for decades by translators, scholars and Modernist poets who imitated the unintentional unintelligibility of the poetess of Lesbos. Kenner also points to advances in the field of etymology, to extensive scholarship in Sanskrit, Anglo Saxon, Provencal, Arabic, Chinese by Modernist poets and scholars, to Skeats’ Etymological Dictionary, famously poured over by James Joyce. Ezra Pound’s Cantos, he tells us, contain archaic words, “borrowing from the Greek, Latin, Chinese, Italian, French, Provencal, Spanish, Arabic, and Egyptian Hieroglyphic language; this list is not complete. And as for The Waste Land…; and as for Ulysses…; and one shrinks from a linguistic inventory for Finnegans Wake, where even Swahili components have been identified. The province of these works, as never before in history, is the entire human race speaking, and in time as well as space…” (95). There was, Kenner continues, an attempt to return old words to usages that were thought to contain more force and latent magic than modern watered-down words. Eliot studied Sanskrit circa 1910; Kenner explains: “It was with the example of a scholarship committed in this way to finding the immemorial energies of language that he perceived how the most individual parts of a poet’s work ‘may be those in which dead poets, his ancestors, assert their immortality most vigorously.’ And also how in language used with the right attention ‘a network of tentacular roots’ may reach ‘down to the deepest terrors and desires’” (Kenner quoting Eliot in “Tradition and the Individual Talent” and “Ben Johnson,”110).

European and native dressed in Kwakiutl costume. via Wikipedia

European and native dressed in Kwakiutl costume. via Wikipedia

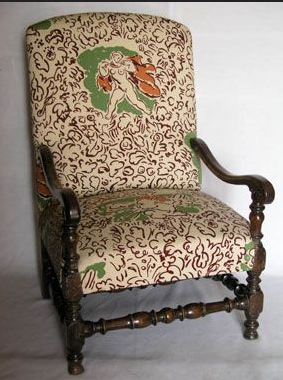

So what did the Modernists mean when they spoke of “Primitive”? And where were they receiving their impressions and examples? The word “primitive” was used rather indiscriminately to refer to the art of European, Russian, and American folk culture, Anglo-Saxon poetry, Medieval Christian artifacts, as well as more exotic art works, crafts, and ritual objects from cultures such as Africa, Oceania, or Australian Aboriginal regions. The indigenous examples were found, naturally, close to home, in still extant country crafts and peasant lifestyles. While an interest in national folk culture was thriving in the Romantic era, it mixed, in Modernism, with international enthusiasms for the art and craft of the “other,” fueled by colonialist and anthropological activity. There were, of course, the now scandalous displays, wherein “exotic peoples were presented in virtual zoological exhibitions or tableaux vivantes.” Since 1851, London’s International Exposition had included representations of “colored peoples”; in Paris, from 1875 to 1889, Expositions Internationales included “native villages”.{{5}}[[5]]Ronald Bush. “The Presence of the Past: Ethnographic Thinking/Literary Politics,” in Prehistories of the Future: The Primitivist Project and the Culture of Modernism, ed. Elazar Barkan and Ronald Bush, Stanford U P, 1995, 23-41.[[5]] The St. Louis’ World fair, where a young T.S. Eliot and his family visited, featured “a comprehensive anthropological exhibition, constituting a congress of races, and exhibiting particularly the barbarous peoples of the world, as nearly as possible in their native environments” (Bush 25). “Groups of pygmies from Africa, ‘Patagonian Giants’ from Argentina, Ainu Aborigines from Japan, and Kwakiutl Indians from Vancouver Islands, as well as groups of Native Americans gathered around prominent Indian Chiefs including Geronimo, Chief Joseph, and Quanah Parker”(26). Ethnographic museums, filled with artifacts and dioramas of primitive life, were frequent throughout Europe in the 19th century, but the Modernist rediscovery of these objects moved them from out of the realm of anthropology into the realm of High Art and the Art Museum, arranging influential exhibits, such as a 1914 “African Negro Art” show in New York City. African masks from the Ivory Coast, Gabon, the Congo, featuring stiff frontal poses, closed form, abstraction, and direct carving were the most common influence on Parisian artist circles before 1918; in Germany around 1909, Expressionists were influenced by Oceanic tribal sculpture and relief carvings of the Palau Islands of Micronesia, characterized by decorative motifs and surface patterns. The German Expressionist groups Die Brücke and Der Blaue Reiter took inspiration for their wood cuts and paintings from these carved beams, copying mythological scenes, exaggerated genitals, and formal simplifications. They decorated their homes and studios with 6th century Indian paintings, Javanese shadow puppets, and wall hangings.

From the Caroline Islands, Belau (Palau), 19th-early 20th century via Wikipedia

From the Caroline Islands, Belau (Palau), 19th-early 20th century via Wikipedia

Another important feature of the Primitivism craze was a tendency to raise craft and applied art to a higher level. Kandinsky copied the clothes and costumes of peasantry; he and his consort Gabrielle Munter “filled rooms with folk crafts executed in native styles, including Russian ceramics, lubok prints, and Bavarian glass paintings [and] decorated the furniture and staircase in a folk art style”}}6}}[[6]]Colin Rhodes, Primitivism and Modern Art, Thames and Hudson, 1994, 31.[[6]]. The London Bloomsbury group, too, especially Duncan Grant and Virginia Woolf’s sister, Vanessa Bell, were involved , through Roger Fry’s Omega Workshops, in creating designs “based on the assumption of the moral superiority of peasant handicrafts”. Bohemians all over European and American cities cultivated the Primitive style in dress and home design, influenced by Diaghilev’s Ballet Russe and other dance costumes and theatre designs, by the advent of the Gypsies into European cities, by African, Indian, and Oceanic Art seen in art exhibits and reproductions, and by a desire to follow their Modernist precursor Charles Baudelaire “anywhere, anywhere out of this world”.

The Tub, Duncan Grant, circa 1913. Painted after seeing Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon.

The Tub, Duncan Grant, circa 1913. Painted after seeing Picasso’s Les Desmoiselles d’Avignon.

This search for the exotic led to a celebration of the outsider as subject matter in art, and of course to a mixing between high and low culture within the demi monde cafés, salons, and art happenings of the avant-garde metropolises: gypsies, circus people, criminals, prostitutes, variety performers, models, adventurers, mingled with bourgeois wannabe’s and tourists, aristocratic art collectors, and slumming members of accepted society.

Despite Modernism’s affiliations with the metropolis, Nature was often synonymous with the primitive, “embracing,” writes art historian Colin Rhodes, “a complex set of ideas, ranging from visions of the primordial landscape to the part of the human mind that was untouched by the learning process that one underwent in the civilized west…women and children were closer to nature, and therefore more primitive than men…modern primitivists raised them up as an ideal to which all, whether male or female, should aspire…” (67). Rural artists’ communities cultivated the fashion of “going away,” which often featured nudism and other back-to-nature concepts such as vegetarianism, spreading the idea that a revitalization of culture could spring from a period of regression and more direct modes of living (32). The German Expressionist Ludwig Kirchner’s favorite poet was Walt Whitman, whose 1855 Leaves of Grass had presaged a return to natural innocence while simultaneously breaking down traditional poetic forms.

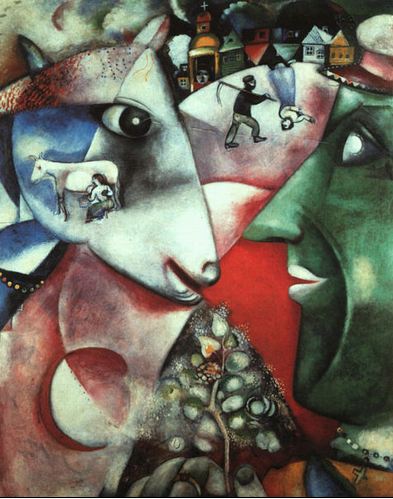

Marc Chagall, I and the Village, 1911. Chagall was part of the Neo-Primitivist Donkey’s Tail Group. via Wikipedia

Marc Chagall, I and the Village, 1911. Chagall was part of the Neo-Primitivist Donkey’s Tail Group. via Wikipedia

Alexander Shevchenko (1880-1978), a member of the Russian Avant-Garde, combined interest in the culture of the peasantry with French Cubism. In a 1913 manifesto for the “Neo-Primitivism” of the Donkey’s Tail Group Exhibition, he wrote of the turn away from Naturalistic painting as a response to the disappearance of physical nature and the dominance of the factory town: light, he writes, “is created by the electric suns of the night … nature does not exist without cleared, sanded, or asphalted roads, without water mains… without telephone or tramway”. “We are,” he continues, “endeavoring to find new paths for our art, but we do not reject the old forms altogether, and of those we acknowledge, above all primitive art, magical tales of the ancient Orient [by which he means Russia]. The simple and innocent beauty of the lubok [Russian Icon painting], the austerity of primitive art, the mechanical precision of construction, the stylistic nobility and beautiful colors gathered together by the creative hand of the master artist”.{{7}}[[7]]Art in Theory, 1900-2000: An Anthology of Changing Ideas, edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood, Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2009.[[7]]

Primitivism, then, was also a protective measure necessitated by the horrors of industrialization and mechanization, which threatened to de-soul man. The Bloomsburian Clive Bell, theorist of Modern art, wrote: “If Expressionism behaves in an ungainly, violent manner, its excuse lies in the prevailing conditions it finds. These really are the conditions of a crude and primitive humanity… As primitive man, driven by fear of nature, sought refuge within himself, so we too have to adopt flight from a ‘civilization’ which is out to devour our souls”{{8}}[[8]]Bell, Clive. Art. New York: Capricorn Books, 1958.[[8]]. The Primitivist critique—similar to Montaigne’s suggestions in his 1580 essay “On Cannibals” — often asserted that modern civilization, its supposed rationality and propriety, harbored horrors equal to those of the savage jungles of Africa. Some of these horrors were to be discovered in the minds of the insane, or even the minimally neurotic or hysterical.

By Adolph Wõlfli (1864-1930), one of the “insane artists” in the Prinzhorn Collection.

By Adolph Wõlfli (1864-1930), one of the “insane artists” in the Prinzhorn Collection.

An interest in the art of the insane, which was—to the admiring Modernist artists— uninhibited, raw, honest, unadulterated by social indoctrination, was cultivated by Hans Prinzhorn’s Collection of the Art of the Insane and his 1922 book, Artistry of the Mentally Ill. Modernists noted, according to Rhodes, the “obsessive primitive mark-making of drawings by schizophrenics (55) and theorized about the creative force of madness. An article in a 1921 Berlin Weekly by Wilhelm Weygandt equated Klee, Kandinsky, Schwitters, Kokoschka, Cezanne, and van Gogh with the lunatics of the Prinzhorn collection; Paul Schultze-Naumberg, in his1928 book Kunst und Rasse (Art and Race) juxtaposed portraits by Expressionist painters with photos of the deformed, the mentally ill, and lepers. A 1933 Exhibit juxtaposed children’s art, modern art, and art of the insane, and the Nazi Degenerate Art exhibit of 1937 famously placed the distorted, disturbing, and abstracted art of Modernism and the Avant Garde side by side with more heroic and classical pieces, attempting to demonstrate the dangers of the primitive influence.

Facing pages from Paul Schultze-Naumberg’s Kunst und Rasse (1928)

Facing pages from Paul Schultze-Naumberg’s Kunst und Rasse (1928)

Critiques of primitivism, however, did not come solely from reactionary circles: in his essay “Ornament and Crime,” Adolf Loos, one of the founders of Viennese Modernist architecture and design, railed against what he saw as a superfluous, meaningless, and childish decorative urge in his fellows, comparing those who indulged in primitive-inspired ornament to children and tattooed savages, prophesying that in the future, sophisticated, modern people would eschew the practice of ornamenting sparse, clean, and crisp open spaces—on skin, paintings, or building facades—with occult or meaningless decorations.

Clive Bell, ignoring such aspersions, analyzed Modernist art with the assumption that everyone found primitive art “mysterious” and “majestic,” explaining that “in primitive art you will find no accurate representation; you will find only significant form.” Looking, he writes, at “Sumerian sculpture…pre-dynastic Egyptian art…archaic Greek… the Wei T’ang masterpieces…early Japanese works…primitive Byzantine art of the 6th century…or…that mysterious and majestic art that flourished in Central and South America… in every case we observe these common characteristics — absence of representation, absence of technical swagger, sublimely impressive form” (114).

This theory of “significant form”—a theoretical basis for both Symbolism and Abstraction—has its roots in the study of Anthropology, which preceded and accompanied the advent of Modernism. Sir James Frazer, who published his 13 volume The Golden Bough between 1890 and 1914, laid the groundwork for an influential comparative religious theory of metaphoric mysticism which, despite any failings as hard science or even rigorous anthropology, permeated Modernist art and psychology for decades to come. For those who have not dipped into this fascinating repository of details and data, the work examines the fertility cycle of ancient mystery religions and its recurrent variations and manifestations in subsequent primitive cultures. His images, filtered through Jessie Weston’s From Ritual to Romance, famously provided an inspiration for T.S. Eliot’s Waste Land. Freud’s anthropological speculations, his idea of the parricidal urge, owe much to Frazer, and it is hard to imagine the development of a popular theory of symbolic magic without Frazer’s work. In short, Frazer tells of a Divine King of the Wood, whose aging, debilitated body is the cause of an unfertile Nature (the waste land). In order to restore fertility, the king must be killed or replaced by a perfect youth, as spring follows winter. The new king enters the sacred grove and plucks the golden bough—a vegetative manifestation of the powers of fertility—and all is put in order again. Aside from the important fact that Frazer’s work was widely read, thus introducing people to examples and illustrations from comparative anthropology and religion, extant primitive tribes, ancient mystery religions, and early medieval cults, this work is important because of its emphasis on the belief in the real-world effect of symbolic action—translated by Modernist artists into a belief in the possible physical effects of their works of art, raising the stakes of formal variation to a higher level.

Freud, taking his cue from Frazer, breaks up the development of consciousness into three categories: animism, religion, and science. Animism, related to what he calls, “Omnipotence of thought”, is, in the neurotic and the “savage,” a belief that thoughts can alter physical reality : “Only in one field,” he writes, in Totem and Taboo, “has the omnipotence of thought been retained in our own civilization, namely in art” (117). He mentions, further, a theorist named Reinach, whose1909 book, L’Art et la Magie (Art and Magic), posits “that the primitive artists who have left us the scratched or painted animal pictures in the caves of France did not want to ‘arouse’ pleasure, but to ‘conjure things’” (118). If animism supposes that man’s thoughts and actions (including art) create reality, then religion supposes that gods, through the intercession and prayer of mankind, effect and create reality. Science, finally—according to Freud—is a way of looking at the world wherein man is small and helpless in the face of absurd and amoral forces. It is, in this context, easy to see why modern man would be drawn back towards a more existential model wherein he might have some power over his environment and future.

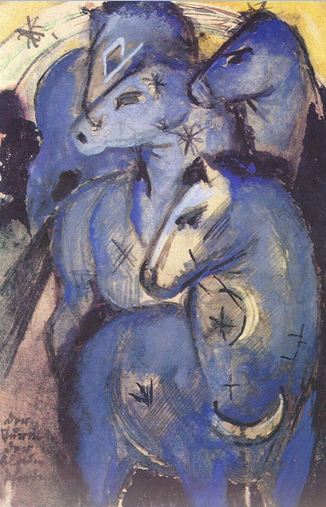

Franz Marc Der Turm der blauen Pferde, 1912/1913. Marc was a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) mentioned above.

Franz Marc Der Turm der blauen Pferde, 1912/1913. Marc was a founding member of Der Blaue Reiter (The Blue Rider) mentioned above.

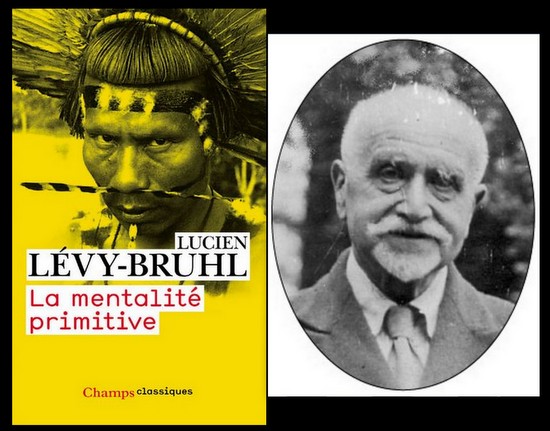

Another central anthropological text, Lucian Lévy-Bruhl’s How Natives Think, published as Les fonctions mentales dans les sociétés inférieures (1910), took issue with Frazer’s evolutionary comparison, positing that the natives’ thought process was not inferior or under-developed, but a wholly other way of thinking, which he called “mystical participation,” a process whereby a representation of an object or person, or a piece of an object or a person’s hair or fingernail, was thought to contain the full force or mana of the so-called original. This conception, related to Western Christian practices of Eucharist or the prohibition of idol worship, was re-introduced and re-packaged for European and American audiences as something exotic and pre-logical, and helped thereby to lay the foundations for a primitivist aesthetic theory of symbolic significance.

The fact that such mystical conceptions already existed in our culture was blithely overlooked by even the anthropologists, who — avoiding the idea that Western cultural history might be in any way irrational—presented these notions as beyond the pale of our comprehension. Lévy-Bruhl writes: “It is the direct result of active belief in the mystic properties of things, properties connected with their shape, and which can be controlled through this, but which would be beyond the power of man to regulate, if there were the slightest change in form. The most apparently trifling innovation may lead to danger, liberate hostile forces, and finally bring about the ruin of its instigator and all dependents upon him”{{9}}[[9]]Lévy-Bruhl. How Natives Think, trans. Lillian Ada Clare. G. Allen & Unwin, 1926, 42.[[9]]. Such innovations, then, were to be avoided in the realms of art, craft, building, clothing, or rituals, if a society wished to maintain its status quo; in the case of our Modernist revolutionaries, on the other hand, alterations of traditional Form would be seen as a means to change the world, or, at least, the way in which we see it. William Butler Yeats— who, to his credit did make connections to forms of Western mysticism and the secret irrational and occult in his own culture —writes, in a 1900 essay on Symbolism: “…I am certainly never sure, when I hear of some war, or of some religious excitement, or of some new manufacture, or of anything else that fills the ear of the world, that it has not all happened because of something that a boy piped in Thessaly”.{{10}}[[10]]Yeats, “The Symbolism of Poetry,” The Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, Vol. IV, Early Essays, 116.[[10]]

Whether artists actually believed, like the composer Alexander Scriabin — who avoided finishing a composition for fear that its completion would impel the universe to explode —that their work would physically transform the world, the rhetoric of symbolic effectiveness permeated artistic discourse, and abstraction was seen, by many, as a means to contain and to conjure. Since, moreover, an abstract image or symbol—however crudely depicted —might contain the spirit of a person or idea just as well as —or even better than—an exact representation, realistic mimesis came to be seen as more of a hindrance to direct mystical participation than a help. In his 1914 programmatic book Art, Clive Bell wrote: “The representative element in a work of art may or may not be harmful; always it is irrelevant…Art transports us from the world of man’s activity to a world of aesthetic exaltation. For a moment we are shut off from human interests; our anticipations and memories are arrested; we are lifted above the stream of life…”( 115). Wilhelm Worringer, whose 1906 Abstraction and Empathy was reprinted for over 40 years and provided another important theoretical basis for the link between Primitivism and Modernism, combatted what he called the “European-classical prejudice of our customary historical conception and valuation of art”.{{11}}[[11]]Worringer, William. “From Abstraction and Empathy.” In Art in Theory, 1900–2000, edited by Charles Harrison and Paul Wood. Malden, MA: Blackwell, 2009.[[11]] The urge to abstraction,” he continued, “stands at the beginning of every art” and is a result of “an immense spiritual dread of space”(70). Abstraction for early man—and, he suggests, for the Modernist —provided a comfort in a world of confusion. He continues: “…the possibility of taking the individual thing of the external world out of its arbitrariness and seeming fortuitousness, of externalizing by the approximation to abstract forms, and, in this manner, finding a point of tranquility and a refuge from appearances,…to wrest the object of the external world out of its natural context, i.e., of everything that is arbitrary…”(71). And, finally, Worringer, quoting Arthur Schopenhauer, tells us that modern man is, indeed, in the same place as Primitive man had been: “Having slipped down from the pride of knowledge, man is now just as lost and helpless vis-à-vis the world picture as primitive man, once he has recognized that this ‘visible world in which we are is the work of Maya, brought forth by magic, a transitory and in itself unsubstantial semblance, comparable to the optical illusion and the dream, of which it is equally false and equally true to say that it is, as that it is not’” (71). Worringer differentiates between societies of abstraction and (post-Renaissance) societies of expression, which, for the Modernists, according to Kermode, can be distilled into the formula: “Bad art is dependent on external explanation, external reference, on trying to utter what is unutterable[…] Thus,” Kermode continues, “there grew up a new veneration for art that leaves out, and so has a chance of containing the unutterable —art under a new aspect, indistinct, calling one back to rough ground, demanding that one look, and see what is not palpably there: connections, interrelations, gaps signifying the unuttered” (366). “One thing Modernism taught us,” Kermode writes, “was just this: that writing can be taught to take account of what it cannot explicitly express” (359). Not only could writing or visual art be taught to take account of the ineffable; it was also theorized that the success of a work of art, even if it did refer to specific things, ideas, or people, was not dependent upon the viewer or reader sharing the particular references or private language of the artist. According to Kenner, the Romantics had found that mysterious correspondences in poems from earlier eras —mysterious because the 18th century reader no longer shared the cultural referents of a 16th century writer —had an “effect” —“too subtle for the intellect”. The Modernists took this a step further and “were,” he writes, “aiming at [these effects] by a deliberate process” (130). “‘Genuine poetry’, wrote Eliot in 1929, ‘can communicate before it is understood’” (123). And Pound, taking this yet farther, theorized that poetry could be understood by a reader “who,” writes Kenner, “could not fill the ellipses back in, who literally, therefore, didn’t know what the words meant”(133) “[W]ords, he continues, are “set free, liberated in magnificent but sober nonsense, which however beaten upon will not disclose meaning” (135).

The Primitive, therefore, which the Modernist could not translate logically into meaning, not sharing in any significant way a cultural referent or history, is the perfect model for something unintelligible which still seems to speak to us. While much is lost going over the precarious bridge of non-linear, subjective expression, we arrive, nevertheless, somewhere very different than we would have had our images and words been instantly translatable into quantifiable meaning. Perhaps, as many Modernists believed, we would arrive in a place that all humans might recognize: outside of civilization, history, logical language, and individual cultural experience, and share, for a moment, some unutterable knowledge. The contact with the art of the other, whether fully understood or boldly appropriated, allowed entrance into what they conceived of as entirely new worlds. But the silent hauntings of indecipherable symbols and abstractions have entered and blown our minds to the extent that we no longer even know what was ours and what was theirs. Modern day multiculturalism seems like a forced but weak trickle of water in comparison with the frenzied rush accompanying these early contacts. Because they couldn’t help but find what they were looking for, it might not be too far-fetched to imagine that the Modernists, when they opened up the passage into other realms and encountered the artifacts and spiritualities of the people they designated as primitive, were actually encountering nothing but their own subconscious minds — seen through the protective veil of the other. This uncertain journey into the pre-logical or aesthetic realms, amid fresh images and formal surprises, came to define the experience of art in the 20th century, an art whose aim was not to “please and instruct,” but to challenge the viewer or reader to change his or her life. How far we have come today, in an art world informed by concept and message (instruction without the pleasing?), and often derisive or neglectful of the powers of formal arrangement or aesthetic experience, is material for another essay altogether.

—Genese Grill

.

Genese Grill is an artist, writer, German scholar, and translator living in Burlington, Vermont. Her first book, The World as Metaphor in Robert Musil’s ‘The Man without Qualities’: Possibility as Reality (Camden House, 2012), explores the aesthetic-ethical imperative of word and world-making in Musil’s metaphoric theory and practice and celebrates the extra-temporal moment of Musil’s “Other Condition” as a transformative aesthetic and mystical experience informing a utopian conduct of life.

Genese,

Under the weather from a summer flu, I was about to stumble into bed fairly exhausted–until I was revivified by this exciting journey into the interior of the modernist mind. There can’t be many encounters more significant than that between early 20th-century artists and writers and the “primitive,” especially since, as you argue, the encounter turned out, paradoxically, to be with themselves. We can’t even speak of an “interaction” between modernism and primitivism since, as you show, the former would hardly exist without the recognition and internalization of the latter.

You refer to those ready to follow Baudelaire “anywhere, anywhere out of this world.” They were following him and the other Modernists out of 18th/19th-century European rational civilization that culminated in the trenches of the First World War, the ultimate nightmare of Reason predicted by the Romantics, That’s “paradox” enough; but, as you also note, primitivism was at once a Dionysian danger to Apollonian order and a source of power over our external world, giving, in Clive Bell’s phrase, “significant form” to the absurd, amoral chaos of the modern world.

Unsurprisingly, given the immersion of Eliot, Joyce, and Yeats in in Fraser’s “Golden Bough,” primitivism performs precisely the role Eliot assigned, in his famous review of Joyce’s “Ulysses,” to “the mythical method,” a method he described as perfected by Joyce, and “adumbrated” by Yeats. In primitivism, as you beautifully illustrate, a significant number of formidable painters, sculptors, and writers encountered in the primordial Other their own subjective minds; and in the process of that Aristotelian “recognition” created an explosion of energy and art to rival the Renaissance.

Thanks again for this informed, exuberant, encyclopedic romp through intellectual, mythical, and, above all, aesthetic history. And so, finally, to bed–this time fully exhausted, but wiser.

Pat .

PS In the final sentence, the second “or” is a typo for “of.”

Thank you, Pat. As always, you honor me with your kind words and make me grateful of the gift of discourse. There are, indeed, a few typos (it is no wonder you are named “keen”! I hope you are feeling better and that while you were sick you at least enjoyed some vivid and beautiful dreams (emanating from the feverish subconscious primitive abysm). I am also laboring under a summer cold, but have not yet managed to turn the inevitable slackening of my logical faculties to any profitable artistic account!

Thanks,Genese, I am feeling a bit better. I forgot to mention how much I thought the wonderful “subconsious” illustrations added to your essay. A few of those explosions of color–the opening Emil Nolde, of course, but also the Chagall and Franz Marc–contributed to invigorating me last night. This is just one of the cool aspects of publishing in NC.

Yes! Images courtesy of the inimitable Douglas Glover!

Thanks, Genese. It was a pleasure to read carefully through the essay and then look up references and pictures and see the commentary there and then see how things fit within the essay. And this time I deployed a bunch of combination images, which I’ve only used rarely before.