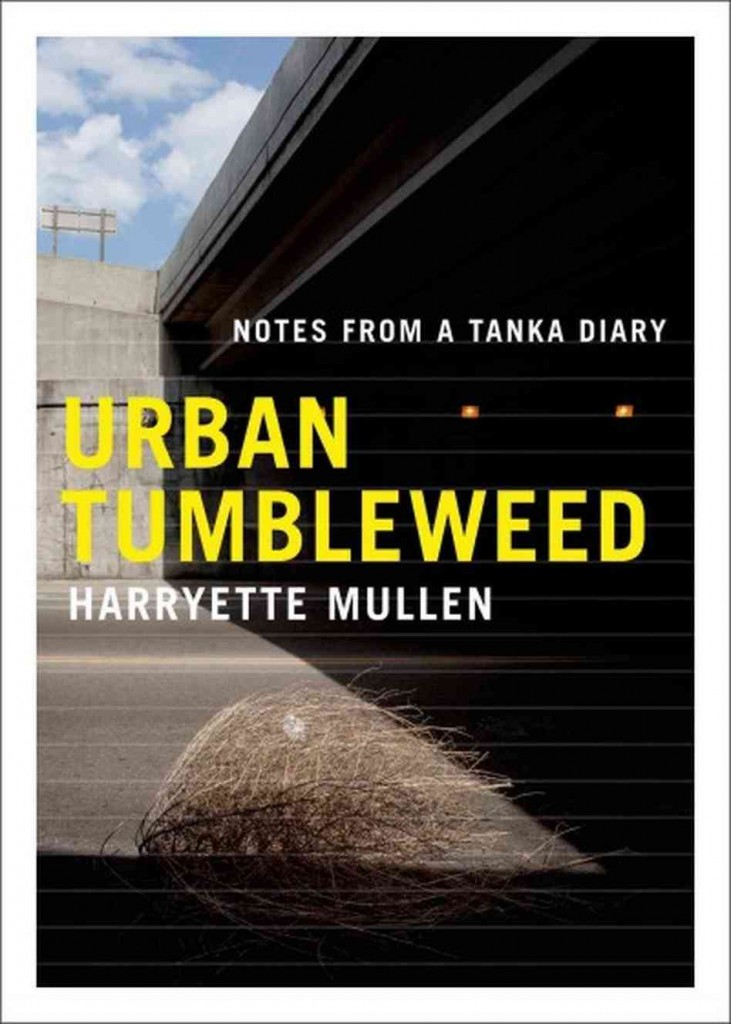

Urban Tumbleweed: Notes from a Tanka Diary

Harryette Mullen

Graywolf Press

120 pages, $15

ISBN: 978-1-55597-656-9

Walk, don’t run, or you’ll miss it—Harryette Mullen’s feat of taking to her feet to capture the hum of bees in the botanical garden, droning of news headlines, and blare of vuvuzelas, all within 31 syllables. In Urban Tumbleweed: Notes from a Tanka Diary, Mullen’s daily discipline of walking and writing tanka poems blossoms page-by-page into this reflection on nature and human nature.

Born in Alabama, Mullen grew up in Texas, and received degrees from University of Texas and University of California at Santa Cruz. She published her first book, Tree Tall Woman, in 1981 and went on to write several more including Trimmings (1991), S*PeRM**K*T (1992), and Muse & Drudge (1995) (Graywolf collected these three books in Recyclopedia in 2006). She is a language poet, influenced by Gertrude Stein among others, also known for her wit and humor and her interest in social activism. Mullen is now an English professor at UCLA, teaching creative writing and African-American literature. A decade has passed since her collection, Sleeping with the Dictionary, which was a finalist for a National Book Award, National Book Critics Circle Award, and Los Angeles Times Book Prize.

In the introduction to this new work, Mullen claims to be engaged with merely taking walks and writing poems, on a mission of personal health, mind-body alignment, and closer observation of human-versus-nature duality. This book doesn’t flaunt her wondrous powers of poetic play, punning, and language games, which are showcased in her previous collections. The real accomplishment of this collection occurred to me while I spent a couple of days without my car, walking my usual school-home-work circuit after hitting a high-bouncing soccer ball on a six-lane highway. Urban Tumbleweed offers up the beautiful heartbreaks of encounters in an urban ecosystem. Mullen’s skillful subversion of stereotypical thinking has merely taken on a stealthier strategy in her diary of 366 days of walking and writing.

In Urban Tumbleweed, Mullen uses her own variation on tanka, which is a Japanese form traditionally written in a single line with a syllabic pattern of 5-7-5-7-7. When translated or written in English, the poems usually take line-breaks at the end of each syllabic unit. Mullen’s variation adheres to the 31-syllable limit but uses a three-line format. Throughout the book, a consistent layout of three poems per page promotes a sense of conversational tension across the gutter of every page-spread. An example from early in the collection of two poems directly facing each other:

Flowers of evergreen tree called bottlebrush,

not stiff bristles but velvety filaments,

leave fingers brushed with yellow pollen.

Flame tree, I must have missed your season

of fire. All I see are your ashy knees, your kindling

limbs, branches of extinguished blossoms.

The images of pollen-dusted fingers and ashy knees overlap subtly across the page, bringing into focus the conversation between human and nature. In other instances, poems contrast sharply with each other, as in this example of facing-page poems from near the middle of the book:

These colorful little stucco houses in

Sunkist Park don’t look so bright today

beneath this overcast sky of cloudy gray.

We’re jerked awake as helicopter blades beat air.

Light glares from above. An amplified shout

orders a fleeing suspect to halt.

Darkness in the middle of an ordinary day versus blinding brightness in the middle of the night sets up the scene for the two poems beneath each of them, which push and pull against each other with complaint, image, and specific observations.

A shivering dog left out in the rain,

dripping wet and cold as a miserable

werewolf, each raindrop a silver bullet.

My usual half-hour ride to work took

two hours today because the president

returned for another fundraiser.

Expressions of complaint and keenly observed natural detail define Japanese poetic diaries, including classics as Matsuo Basho’s The Narrow Road through the Provinces and Masaoka Shiki’s A Verse Record of My Peonies. Ki no Tsurayuki, an acknowledged master of the tanka form and one of the compilers of the first imperial anthology of tanka poetry, invented the Japanese poetic diary with The Tosa Diary (935 CE), a fictional account from a female protagonist’s point-of-view based on his own travel experience with a group returning to Kyoto from a distant province. The discomfort of travel by boat, unfavorable weather, and her recent loss of her young daughter set the scene for many poems of longing, hope and sorrow. Different characters compose and recite tanka poems, which Tsurayuki varies according to their roles and personalities in the story. The overlaps and contrasts seen in Mullen’s collection are abundant in this and other Japanese poetic diaries. A short excerpt from Earl Miner’s translation of The Tosa Diary:

The 4th

The captain said, “The condition of the wind and the sky is extremely unfavorable,” so that it has not been possible to put out the boat. All the same, neither the wind nor the waves rose so high. This captain really seems unable to tell anything about the weather. On the shore of this harbor there are many beautiful little shells and pebbles. For all their beauty, because they are just the sort of thing she would have liked to gather, they remind me of my little girl who has passed away. I made a poem.

Beating upon the shore,

O waves, I wish that you would bring

Shells of forgetfulness

That I might pick a shell of comfort

From the heavy thoughts of her I love.

When I spoke the poem, there was one with us who was unable to remain silent and made a poem on the sufferings of our voyage.

Shells of forgetfulness—

Not they the things I shall take up,

But pretty pebbles

To remind me of a precious child,

To be a souvenir of her I loved.

Mullen also shares a little of this collaborative effect of writing tanka:

After hearing that poem from my tanka diary,

you handed me a smooth and pleasing stone

shaped like a lopsided heart.

A kind friend sent me a hastily scribbled note,

inquiring about my “tanka dairy.”

I wrote back to say, “I’m milking it.”

Because her poetic has tussled directly with identity politics throughout her work, I was surprised to find so little obvious sign of it in her approach in this collection. From her poetic statement in American Women Poets in the 21st Century:

My desires as a poet are contradictory. I aspire to write poetry that would leave no insurmountable obstacle to comprehension and pleasure other than the ultimate limits of the reader’s interest and linguistic competence. However, I do not necessarily approach this goal by employing a beautiful, pure, simple, or accessible literary language, or by maintaining a clear, consistent, recognizable, or authentic voice in my work. At this point in my life, I am more interested in working with language per se than in developing or maintaining my own particular voice or style of writing, although I am aware that my poems may constitute a peculiar idiolect that can be identified as mine. I think of writing as a process that is synthetic rather than organic, artificial rather than natural, human rather than divine. My inclination is to pursue what is minor, marginal, idiosyncratic, trivial, debased, or aberrant in the language I speak and write. I desire that my work appeal to an audience that is diverse and inclusive, at the same time that I wonder if human beings will ever learn how to be inclusive without repressing human diversity through cultural and linguistic imperialism.

The following consecutive poems veer toward explanation of Urban Tumbleweed’s method:

This curly cloud don’t grow straight or need

straightening. It takes rough wind to wreck the ‘do.

To some, when brushed and combed it still looks tangled.

You could say I am borrowing light

from the moon when I write my tanka

after reading translations of Princess Shikishi.

Toward the end of the collection, the cross-talk between tanka poems increases as does the musicality of the individual poems. These two poems across the middle of their pages speak of “head” versus “heart”:

At first, the dog walker mistook it for a horror-

movie prop—that severed head found in the park,

beneath the HOLLYWOOD sign.

The heart of a saint, stolen from a church

in Dublin. Thieves leave golden chalices,

costly art, choosing this most priceless relic.

Some of my favorites from the collection accomplish together the inclusiveness that Mullen strives for with a touch of humor, especially where nature turns around and examines the poet. In one a hummingbird momentarily mistakes the poet in her red dress for a giant flower. And much later in the collection:

“Who do you think I am? Tippi Hedren

in an Alfred Hitchcock film?” I wondered,

when that flying object pecked me on the head.

Another represents Mullen’s intent throughout the collection with this:

TUMBLEWEED, name in black letters

on the side of a bright yellow bus

delivering students to open gates of Windward School.

Mullen mentions in her introduction that she leads students on tanka walks in the botanical garden where she teaches. This glorious discipline of the mind and body moving through poetry is better experienced than explained, and Urban Tumbleweed offers a moving invitation.

—A. Anupama

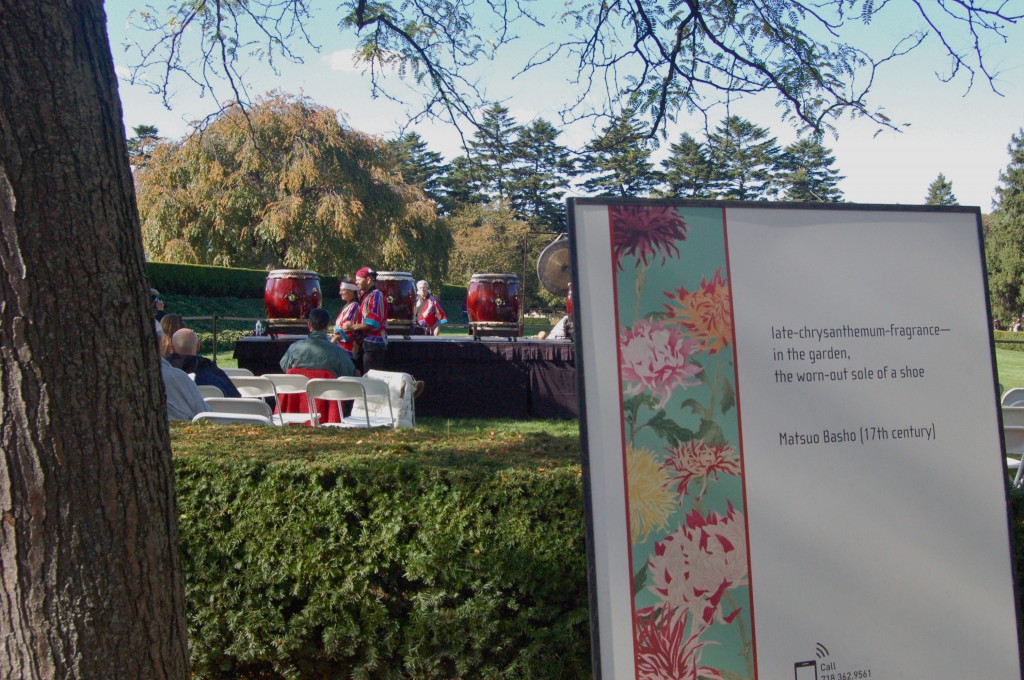

Final photograph of the New York Botanical Garden’s 2013 exhibition, Kiku: The Art of the Japanese Garden, including the drummers from Taiko Masala, and poetry displays co-presented by the Poetry Society of America and curated by Jane Hirshfield.

References:

Rankine, Claudia, and Juliana Spahr, eds. American Women Poets in the 21st Century: Where Lyric Meets Language. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2002.

Miner, Earl. Japanese Poetic Diaries. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1969.

———————————–

A. Anupama is a U.S.-born, Indian-American poet and translator whose work has appeared in several literary publications, including The Bitter Oleander, Monkeybicycle, The Alembic, Numéro Cinq and decomP magazinE. She received her MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2012. She currently lives and writes in the Hudson River valley of New York, where she blogs about poetic inspiration at seranam.com.

A. Anupama is a U.S.-born, Indian-American poet and translator whose work has appeared in several literary publications, including The Bitter Oleander, Monkeybicycle, The Alembic, Numéro Cinq and decomP magazinE. She received her MFA in writing from Vermont College of Fine Arts in 2012. She currently lives and writes in the Hudson River valley of New York, where she blogs about poetic inspiration at seranam.com.

Thanks for this excellent review. I’ve been meaning to read more from this interesting poet, and I’m inspired now to follow through.