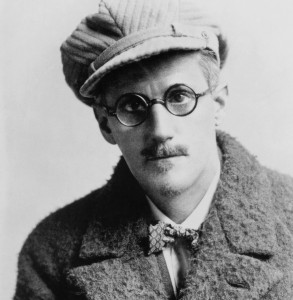

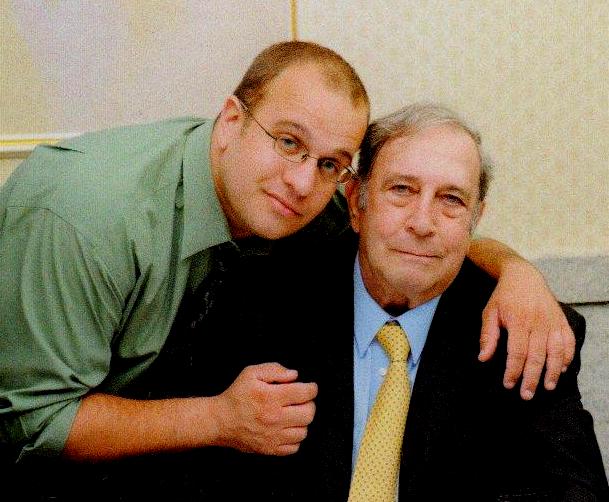

David Foster Wallace. Credit Flickr/Steve Rhodes via Salon.com

A gargantuan book wherein all the glinting particulars of an animate metropolis everywhere dissolve in these shadows of the valley of death? This without ever skimping in the effort to speak a score of deeply personal tongues? Plus just the writer’s resolve to stake a substantial chunk of his lifespan in the manufacture of an irksome and unrepeatable nothing? With this stuff I, for one, can like totally Identify. —Bruce Stone

.

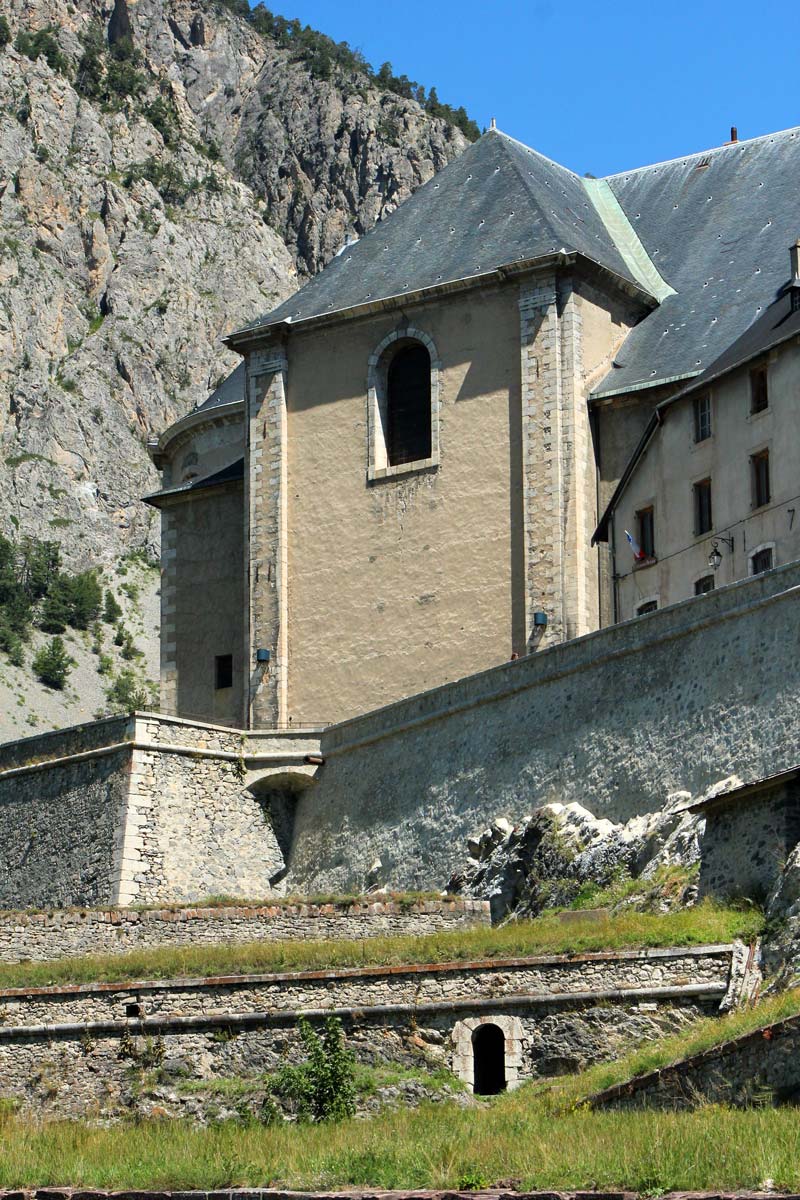

Still from James Ponsoldt’s DFW biopic The End of the Tour

Only the most militant fans of David Foster Wallace will find anything objectionable in The End of the Tour, director James Ponsoldt’s eulogy for the writer, who died, at 46, in 2008.[1] The biographical film has an indie ethos and an all-business cast, though its provenance still begs a double-take. The screenplay is adapted from a 2010 book by David Lipsky, which is itself a reboot of Lipsky’s five-days-long, but never published interview with DFW, this conducted in the far-right margin of the publicity tour for Infinite Jest. So the product that arrived at summer theaters was practically rippled with layers of pre-packaging and spin, but Ponsoldt, for better or worse, just relegates all such abstraction to the dialogue and otherwise keeps his telling as grounded as possible. The loveable schlub Jason Segel plays Wallace, while Jesse Eisenberg does his minimal-affect routine as Lipsky, and Joan Cusack has a bit part as a cartoon Minnesotan. The typecasting alone reflects an earthbound sensibility, so it seems only natural that the film’s real star should be the Midwestern landscape. For tax reasons, western Michigan stands in for Wallace’s central Illinois, and its sprawling flat-earth vistas of thin crusty snow and distant copses dazzle in their sheer ordinariness. Amid those harshly beautiful winter fields, beside a county road that’s dutifully plowed but little traveled, sits Wallace’s house, a long low ranch with cheap-wood finishes and shit-stained carpets (the homeowner keeps two large black dogs), looking improbable and improvised against the elements.[2] Basically, The End of the Tour is a well-intended mash-up of the Coen Brothers’ Fargo and Cameron Crowe’s Almost Famous, mostly harmless.

By my count, Tour contains just two powerful moments, both of which model in a kind of cinematic negative space the daunting edifice of Wallace’s work. Late in the movie, there’s a shot of Wallace’s cave-dark study, where Lipsky takes a rapid and belated inventory, gathering material for his piece. Threads of nuclear sunlight line the apertures in the room’s heavy-gauge curtains, and the stage is set for a blinding dissolve. Even if Plato’s allegory is the furthest thing from your mind, the sequence reads as an eloquent pantomime of Wallace’s achievement.

The second scene is more indicative of the film’s handling, its careful avoidance, of the work it memorializes. When Lipsky first arrives, Wallace invites him to bunk at the house in a “sort of guest room” space. The room in question is furnished with a futon and an assortment of load-bearing flat surfaces on which Wallace’s many books are arrayed in tall and pristine, as if machine-made, towers, the hulking Infinite Jest conspicuous among them. As neither man comments on the absurdity of the decor, the scene comes off as a sight gag, underlining Lipsky’s physical discomfort and competitive rancor. He beds down for the night with Wallace literally towering over him. But something more disquieting rumbles beneath the surface, as if the film has stepped roughshod on a live nerve. The sheer number of museum copies speaks volumes about Wallace’s chilling solitude (he can’t give this stuff away!). Even worse, those vertically stacked bricks of type-written pages suggest something redundant and wasteful and ultimately futile at the end of the labor of writing itself (he can’t give this stuff away!). The printed book never seems more paltry, less adequate to the teeming world it contains, less consistent with the miseries of its creation, than when it’s replicated in mass quantities and warehoused for distribution, smilingly absorbed by the consumer-capitalist system. This is why chain bookstores and Amazon and the little shelf-lined back rooms of publishers’ publicity offices give me the howling fantods (to borrow Avril Incandenza’s phrase).

And this is how the film treats Wallace’s work—it’s part of the furniture, atmospheric rather than elemental. Presented with a chance to show Wallace at the lectern, reading from IJ at a Minneapolis bookstore, the camera averts its eye, opting instead to focus on Lipsky, in the wings, quietly eating his heart out. The film’s narrative loyalties lie with Lipsky’s book, not Wallace’s opus, so it strains to contrive a story arc from the shifting relations, a kind of sibling rivalry, between the writers. These tensions feel manufactured, thin and underwhelming, and there’s something prefabricated or too-convenient in the script’s frame-tale design, the whole interview episode recounted as a flashback after Lipsky learns of Wallace’s suicide in 2008. But the film is earnest and sincere—a level-best effort all around—and if it’s a little flat-footed and embarrassing, it’s embarrassing in the way a mother can be embarrassing when she brags about you in public.[3] The End of the Tour has nothing urgent or revelatory to say about Wallace or his work, and this silence, admittedly, makes it hard to distinguish between pious hagiography and the mercenary selling of graven images. Even so, viewers should brace for impact when a simulacrum of the man first emerges from his Illinois abode to greet Lipsky in the iced-over driveway. The moment has some of the charge of a Christ drolly exiting a crypt, or a dead relative blinking at you non-confrontationally from a photograph. The sight triggered, for me anyway, a wave of grief, long overdue.[4]

.

Into the House that Jack Built

What forestalls any and all hand-wringing over the film’s portrait of the writer is how inconsequential it feels when placed alongside Wallace’s own work, by which I mean mainly, perhaps exclusively, his Infinite Jest—the novel whose sonic boom, even without the artificial stimulus of Tour, we’re still hearing the echo of. Maybe my perspective is a little skewed: I read IJ for the first time in June, two decades too late (my epitaph, I fear) for Wallace’s proper coronation, but right on time for Ponsoldt’s film.[5] Call it kismet.

A quick tour of the web reveals how commonplace, even sadly clichéd, it has become to expound, however tardily, on one’s own personal reading of Infinite Jest. Booster-club testimonials, generous vocabulary dumps, anachronistic reviews, the incremental records of reading-group listservs, why-not-to-read-it spoofs as well as why-to-read-it genuflections: these things are everywhere in cyberspace, constituting in aggregate a kind of DIY sub-genre of literary criticism, DFW & I.[6] Amid the bylines and chatter some distinguished names surface: in 2009 Aaron Schwartz, the digital whiz-kid who ran afoul of the web’s download restrictions, immersed himself unabashedly in the novel’s brain-teasing puzzles, while the Canadian fantasist R. Scott Bakker contributed an elaborate takedown to the archive in 2011. The novel continues to attract casual potshots, as well: Harold Bloom, via Women’s Wear Weekly (no joke), and Bret Easton Ellis, via Twitter, have both lobbed vitriol at Wallace and his readers.[7] Ponsoldt’s film is just part of the vapor trail, in his high-overhead medium, from the novel’s transit. So grant the film safe passage as it lumbers affably from summer cinemas toward DVD-rental outlets everywhere. Meanwhile, the monolith itself, IJ, still beckons, rife with controversy, thick with conundrums, prolix and aloof, meditative and smart and hilarious and searing. If you have to this point, as I did, given wide berth to the beast—if you suspect a lame Pied-Piper fandom in the cult of Wallace—I encourage you strongly to test your scruples against the book itself. With the possible exceptions of heartfelt parenting and excellent sex, nothing is more deserving of your time and attention than Wallace’s Infinite Jest.

This is not to say that the novel is perfect, as in, uniformly without flaw or defect. The givens of the textual world alone range from peculiar to zany: a family saga that conflates Hamlet and The Brothers Karamazov on the grounds of a tennis academy? A North-American map that has been cheekily revised? Calendar years auctioned for naming rights like NCAA bowl games? An army of wheelchair-bound French-Canadians who squeak across the landscape, seeking a doomsday device—in this case, a lethally entertaining videodisc? Most of the novel’s imaginative excesses are entirely palatable, the satire spot-on. But I have to draw the line at, or enclose in squiggly brackets, elements like the Vaught twins, who make a killer doubles team at Enfield Tennis Academy, despite (or because of) being conjoined at the head. Likewise, a few high-drama scenes—an after-hours tryst in the headmistress’ office, a torturous interrogation with some complicated staging, an Inner Infants support group meeting—are insipidly farcical. And the lush filmography of JO Incandenza, one of the book’s ballooning endnotes, is a marvel of erudition, with a number of fine Easter eggs glinting in the bushes; these many films, besides, haunt the whole length and breadth of the big novel, yet I can’t help but imagine their titles voiced by The Simpsons’ Troy McClure: Blood Nun: One Tough Sister, Dial C for Concupiscence, The Night Wears a Sombrero.[8] Note the exclamation point in Accomplice!

Of course, when visiting a grand cathedral, you can stand outside and count the gargoyles or you can head inside to hear the choir. In the case of IJ, bloopers notwithstanding, every page bears the impress of an obvious and undeniable genius. The book is a cacophonic compendium of millennial voices, and Wallace manages to coax something beautiful from each one. He can lampoon the pretensions of the most esoterically high-brow discourse[9]; render the slovenly charms of a smart teenager’s private language (including mathematical geek-outs); lovingly detail the screwy articles, botched possessives, and fouled-up idioms of non-native speakers; and cull a muted poetry from the workaday lexicons of felicidal pimps, reformed burglars, flummoxed psychiatrists, rotten fathers, and transvestite prostitutes. Wallace has an awful lot of fun with catachresis in the book. He does an unforgettable Irish brogue and captures the weirdly crestfallen ecstasy of an overdose in progress, all metastasizing syntax and achingly fine-grained perceptions. More than just reproducing such voices, Wallace textures each with chiaroscuro shadings, catching quirks and nuances, speech tics that slide around fluidly. This virtuoso display is nowhere more evident than in Note 304, a lost-island set piece in which Jim Struck of Enfield Tennis Academy attempts to plagiarize a scholarly work for his term paper in a class he calls “Poutrincourt’s History of Canadian Unpleasantness course thing.” In fact, this endnote encapsulates, in microcosm, the work in all its vastness. Like a slice that gives up the whole loaf, it reveals almost everything you could want to know about the novel: from how to read it or why to bother, to what, if anything, the book has to say to its patient and intrepid auditors.

.

The Endnote

In this sub-basement of a chapter, Wallace simulates not just the puff-cheeked oratory of “US academese,” but the off-the-leash, cognitively impaired rhetoric of a narcotized scholar, this one expatiating on Canadian terrorist cults, the initiation rite of the Wheelchair Assassins in particular. For purely ornamental reasons, the scholar also ties in a mention of the feral infants—a byproduct of toxic waste dumping in a geographic region ceded by the US, with love, to Canada—who otherwise writhe and roil offstage, part of the novel’s emblematic marginalia. Here’s a sample of the scholar’s vocal signature: “Almost as little of irreproachable scholarly definitiveness is known about the infamous Separatist ‘Wheelchair Assassins’ … of southwestern Quebec as is accepted as axiomatic about the herds of oversized ‘Feral Infants’ allegedly reputed to inhabit the periodically overinhabitable forested sections of the eastern Reconfiguration.” For long stretches, the Endnote compiles verbatim citations of this impeccable balderdash, yet the mood of grotesque parody never quite extinguishes a stubborn, oddly poignant verisimilitude.

Intermixed with such passages is the sulky and slang-riddled rambling idiom of the plagiarist, who supplies a running commentary on the article, with the occasional sarcastic flourish:

the hardest work for Struck here is going to be sanitizing the prose in this Wild Conceits guy’s thing, or at least bringing the verbs and modifiers down out of the like total ozone, which the Academese here on the whole sounds to Struck like the kind of foam-flecked megalograndiosity he associates with Quaaludes and red wine and then the odd Preludin to pull out of the grandiose nosedive of the Quaaludes and red wine.

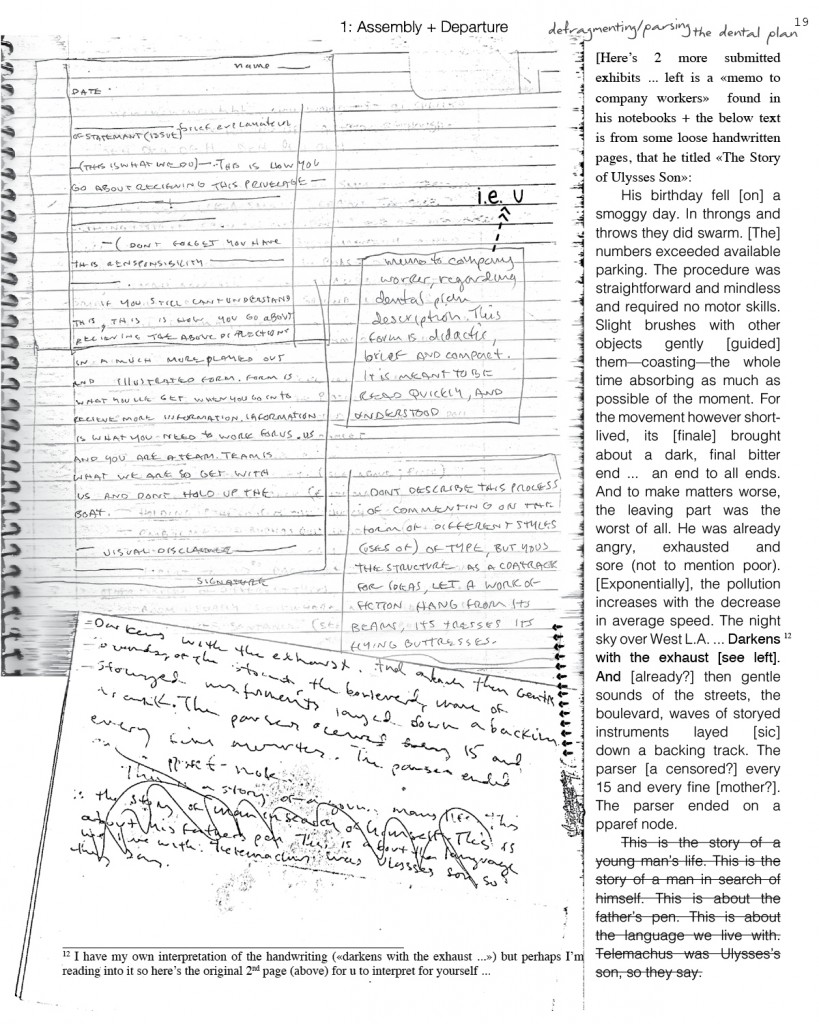

The violence of the code-switching might cause whiplash, but it feels almost seamless because Struck himself is so hilariously preoccupied by the scholar’s whacked-out style: “Struck at certain points imagines himself gathering this Wild Conceits guy’s lapels together with one hand and savagely and repeatedly slapping him with the other—forehand, backhand, forehand.” Carrying the sequence to its logical conclusion, Wallace carves still more layers in the vocal palimpsest when he offers glimpses of the plagiarized paper itself, a kind of hybrid voice, Struck’s redaction of the article. After a paragraph from the scholar, outlining the cult’s test of an aspirant’s mettle—a game of Kierkegaardian “Chicken” with a moving train—we read, “Struck transposes clearly nonadolescent uptown material like this into: ‘The variable of the game isn’t so much a matter of the train, but the player’s courage and will.’” And though Struck is an unusually blinkered plagiarist, Wallace grants him enough perspicacity to imagine his teacher’s marginal comments on the resultant paper (“a big red triple-underlined QUOI?” beside a manic transition) and to observe the Doppler shift in Day’s article, as it crossfades from scholarly exposition into full-blown confabulated narrative.

Wallace is clearly a masterful ventriloquist, yet the sheer number of voices in the novel’s discursive field lays it open to charges of logorrhea, as if the book were kaleidoscopic but not cohesive. The terrible truth about IJ, however, is that, at 1079 pages, it isn’t digressive at all. Wallace’s inexhaustible verbal repertoire is matched by an exacting architectural vision. In an interview, Wallace claimed that his book models the fractal form of a Sierpinski gasket,[10] but the novel supplies an equally apt metaphor by which to grok its artful structure: that is, the book itself poses as an InterLace Entertainment. InterLace is the name of the telecom company founded by Noreen Lace-Forché, the “Killer-App Queen” who supplanted the titans of network television with her outfit’s NetFlix business model, and the company’s moniker feels like a hard nudge[11] from Wallace to mind the myriad interlacements in the novel’s pages. The raucous polyphony bends toward euphony, after all.

Like a thumbnail enlargement in an art book, Note 304 offers a manageable arena in which to observe the design ingenuity. Most obviously, this endnote identifies the author of the Wild Conceits article as one G. T. (Geoffrey) Day, a character who, a hundred-odd pages after we read the note, will turn up casually among the cast at the Ennet House for recovering addicts. The book doesn’t make this connection explicit for readers; Wallace asks us to splice the wires, to notice the subtle and surprising intersections of the characters’ lives.[12]

The Endnote also makes abundantly clear something that most readers could glean from the main text’s plot: that the predicament of the Wheelchair Assassins is analogous to the plight of the ETA tennis team. Struck reads of the elimination-tournament structure of the Separatists’ train-dodging, just as, later, the novel’s readers will encounter an apposite description of tournament protocols when ETA faces Port Washington. To double-underscore in neon the thematic kinship here, the Note offers this appraisal of the cult’s rite of passage: the train-dodging ritual is “intimately bound up with ‘Les jeux pour-memes,’ formal competitive games whose end is less any sort of ‘prize’ than it is a manner of basic identity: i.e., that is, ‘game’ as metaphysical environment and psychohistorical locus and gestalt.” This disclosure boomerangs and dovetails with the coaching philosophy of Gerhard Schtitt at ETA: unburdening himself to an acolyte, Schtitt explains that in competitive tennis “the true opponent, the enfolding boundary, is the player himself…. The competing boy on the net’s other side: he is not the foe…. He is the what is the word excuse or occasion for meeting the self.” Schtitt’s theorizing might sound like self-discovery; that it entails self-annihilation becomes clear as the players court an extreme inhuman stoicism in order to excel. In fact, all of the characters in the book’s three major plot threads share a common struggle: to escape the cage of the narcissistic I, “transcend the self through pain,” whether it be a hard-core, self-abnegating patriotism, the will-suppressing protocols of tennis practice, or the reason-defying bromides of Alcoholics Anonymous. The novel’s thematic unity couldn’t possibly be tighter.

But these are only the most glaring examples of IJ’s structural integrity. To get a glimpse of the subtlety and pervasiveness of the book’s imbrication, consider another putative digression from Day’s article. Toward the end of the Note, Day turns his attentions to a different Separatist group, the Cult of the Infinite Kiss. This faction’s initiation rite involves the lip-to-lip conjoinment of heterosexual faces, which faces then respire alternately a single lungful of breath until the participants pass out from oxygen deprivation. Day’s exposition includes some pointed commentary on the differences between the two terrorist cells, but it also functions as a hyperlink, reminding readers of Orin Incandenza’s nightmare concerning his mother: her disembodied head is bound by tennis string to his own horrified face. Similarly, the crux of the other ritual, that leap in front of a barreling locomotive, reverberates when Don Gately, the novel’s square-headed hero, sports with a Green-line train while at the wheel of a borrowed muscle car. And Struck’s own ineptitude vis-à-vis the French language recalls the incomprehension of the monolingual terrorist Lucien Antitois (broker of “blown-glass notions” and gray-market entertainments) during a pivotal Francophone interrogation.[13] IJ is that kind of book: a massive honeycomb of images and motifs, characters and themes, the whole swarming with so much life that the infrastructure stays mostly concealed. That the novel is, in this way, almost infinitely expandable, is not to say that it’s compositionally loose or entropic.[14]

.

Of Figurants and Revenants

For some readers, this peek into IJ’s motherboard might feel anticlimactic, as if its internal circuitry were just a tangle of arbitrarily crisscrossed filaments—as if, despite the endless verbiage, the book had nothing whatsoever to say. As it happens, this crisis of communication—in which words are mere forms, empty of substance—lies at the very core of the novel (both the species and genera). This is the problem of Hal Incandenza, youngest dynastic son, closeted pothead and on-court rising star at ETA. Hal has a gift for language; he’s read the OED and committed most of it to memory. His term papers testify to his high-order brilliance. Yet, he seems incapable of experiencing, much less conveying, authentic human emotions, even on the intimate subject of his father’s suicide. Per the novel’s blunt diagnosis, Hal shapes fine words, but in a figurative sense emits no sound.

Far from being an anomaly in IJ, Hal’s case is typical, even archetypal, as numerous characters observe this existential gag-rule by force, choice, or mere disposition. Among the more lighthearted examples is Jim Struck’s plagiarism,[15] but for all its goofball comedy, Note 304 also shows how this node of the book goes meta-, constituting an inquest into the nature of writing and reading. Immobilized before his computer (except for “grinding his eye” and picking at his acne), literally engaged in the work of reading qua writing, the plagiarist mouths words parasitically, like an intellectual zombie or prep-school golem for Day’s ideas. The only volitional substance attributable to Struck himself are acts of camouflage, as he converts Day’s prose into “less-long self-contained sentences that sound more earnest and pubescent, like somebody earnestly struggling toward truth instead of flecking your forehead with spittle as he ranted grandiosely.” Struck’s enterprise is pure cynicism: plenty of words, but no sound. Like Hal, Struck has become a figurant.

The novel defines a figurant as a peripheral actor with zero speaking lines in a sitcom (like the anonymous bar patrons in the heavily scripted Cheers!), a visible part of the scenery but existentially muzzled. Against this class of tragic characters, IJ poses another, which would appear to be the figurant’s antithesis: the committed speakers at AA meetings. Such speakers aim to embody total honesty, to tell the truth about their addiction experience, however ugly the truth may be. The listeners, for their part, strive for Identification, a mode of ideal hearing that erases the slash in the classic self/other dichotomy. The book is explicit on this point: “Identify means empathize. Identifying … isn’t very hard to do, here. Because if you sit up front and listen hard, all the speakers’ stories of decline and fall and surrender are basically alike, and like your own.” As a strategy for responding to narratives, identification has garnered some well-deserved abuse over the years; all too easily, identification reverts to simple narcissism in which the reader’s self-interest and prerogative are the ultimate determinants of a story’s value.[16] Wallace has in mind something less obnoxious, a more sincere merger of selves or communion of souls which appears to be lifted straight out of Tolstoy.

In his ingenuously titled treatise “What Is Art?” Tolstoy rejects the notion that literature exists for the reader’s pleasure. Instead, a true work of art, for Tolstoy, occasions the very Identification that IJ exalts:

the receiver of a true artistic impression is so united to the artist that he feels as if the work were his own and not someone elseʹs — as if what it expresses were just what he had long been wishing to express. A real work of art destroys, in the consciousness of the receiver, the separation between himself and the artist — not that alone, but also between himself and all whose minds receive this work of art. In this freeing of our personality from its separation and isolation, in this uniting of it with others, lies the chief characteristic and the great attractive force of art.

Wallace’s novel sometimes reads as a hard-line dramatization of Tolstoy’s ideas. All forms of pleasure are suspect in IJ, symptoms of a self-destructive addiction, the antithesis of purifying pain. But when the novel portrays individual acts of listening/reading, the proselytizing feels humble and low-key, not at all doctrinaire. See the description of Lyle, the unofficial staff guru at ETA: “Like all good listeners, he has a way of attending that is at once intense and assuasive: the supplicant feels both nakedly revealed and sheltered, somehow, from all possible judgment. It’s like he’s working as hard as you. You both of you, briefly, feel unalone.” The pitch of the advocacy rarely runs hotter than this.

But IJ ultimately breaks ranks with Tolstoy, and its portrayal of literature, reading, and writing (all sides of the same equilateral triangle) turns increasingly ambivalent. To see how, we have to consider another character type in the book: the wraith (yes, wraith). Like Hamlet, IJ has a few ghosts traipsing around the castle, and these wraiths hybridize the traits of speakers and figurants, a reconciliation of opposites with dire implications. A wraith, we learn, “had no out-loud voice of its own [figurant], and had to use somebody’s like internal-brain voice if it wanted to try to communicate something [speaker].” Another stipulation vis-à-vis wraith ontology: because wraiths inhabit “a totally different Heisenbergian dimension of rate-change and time-passage,” they must “stay stock still in one place” for vast amounts of time in order to interface with the living.

In both regards, this vision of the afterlife makes the wraith sound a lot like an author figure: the wraith’s telepathic mode of communication (and otherworldly stillness) unmistakably connotes the act of writing. Tolstoy’s manifesto already describes literature as an occasion for mind-melding, but Georges Poulet, in “The Phenomenology of Reading,” captures the truly haunting nature of the experience. Poulet observes that reading is always an assault on consciousness: it “is the act in which the subjective principle which I call I, is modified in such a way that I no longer have the right, strictly speaking, to consider it as my I. I am on loan to another, and this other thinks, feels, suffers, and acts within me.” The book behaves like a software application installed and running on the hard drive of the reader’s mind, temporarily displacing the self. The experience, for Poulet, ultimately verges on spirit possession—he refers to reading as “this possession of myself by another”—but the wraith that Poulet summons isn’t the book’s author: it’s the book itself. Poulet writes, “so long as it is animated by this vital inbreathing inspired by the act of reading, a work of literature becomes (at the expense of the reader whose own life it suspends) a sort of human being, […] a mind conscious of itself and constituting itself in me as the subject of its own objects.” This vision of the book as a portable consciousness that can roam from reader to reader might sound itself like a Wild Conceit; the “self-consciousness of literary texts,” a well-worn phrase, has never been construed so literally. But Poulet’s ideas do help to clarify the author-function of Wallace’s wraiths.[17]

Initially, the wraith incursion in IJ serves to reinforce Tolstoyan aesthetics. As with the book’s other author figures, those gifted AA speakers, colloquy with a wraith makes Identification possible, for both parties now, speaker and listener, author and reader (the roles are reversible in wraith-initiated dialogues). The lone character to consciously converse with a wraith, in a fever dream, later reflects wistfully on the experience: “he has to admit he kind of liked it. The dialogue. The give-and-take. The way the wraith could seem to get inside him. The way he said [the listener’s] best thoughts were really communiques from the patient and Abiding dead.” At such moments, IJ does verge on advocating reading as an antidote to self-destructive narcissism. Even Struck, the most hapless figurant, finds himself attaining Identification, however unwittingly, with the “foam-flecked” disquisition of G. Day. Having diagnosed (accurately) Day’s addiction to narcotics, as he reads yet another head-clutching passage, Struck recalls his own father’s disastrous substance abuse, as if he recognizes his own story there in the style, if not the substance, of Day’s essay. Call it Identification, with an asterisk.[18] Here, too, under the least propitious circumstances, reading provides an occasion for “meeting the self.”

Because reading IJ is an extraordinarily labor-intensive exercise, it would be at least courteous if the book were to recommend the activity, validate the time spent and pains taken. Instead, the book equivocates. The first killjoy irony here is that, in order to hear a speaker or converse with a wraith, the listener/reader must shut down the voice, cancel the self, become essentially a figurant.[19] One group of rapt listeners, as they achieve ideal hearing, must “consciously try to remember even to blink”; in this case, identification is tantamount to petrification, the audience turned to statuary, locked in a state of suspended animation. And even under optimal circumstances, with a communicative wraith aiming for honest self-expression and mutual Identification, the inter-mental communion can feel like “lexical rape,” or so the lone experimentee puts it as the wraith floods his consciousness with unfamiliar, seriously uptown words.

The second irony is less local and more pervasive: namely, if the wraith functions as an author-figure, it also models the plucky reader. When the wraith reveals that it can “move at the speed of quanta and be anywhere anytime and hear in symphonic toto the voices of animate men, but it couldn’t ordinarily affect anybody or anything solid, and it could never speak right to anybody,” it offers a description of the reader’s very experience in turning the pages of IJ. Albeit well short of the speed of quanta and/or choral totality, IJ’s readers do slide unimpeded and unregarded from voice to voice, consciousness to consciousness, likewise powerless to impact the world(s) they survey. Don Gately, in whom the wraith confides, acknowledges the tragic paradox of wraith existence:

Gately lets himself wonder what it would be like, able to quantum off anyplace instantly and stand on ceilings and probably burgle like no burglar’d ever dreamed of, but not able to really affect anything or interface with anybody, having nobody know you’re there, having people’s normal rushed daily lives look like the movements of planets and suns, having to sit patiently very still in one place for a long time even to have some poor addled son of a bitch even be willing to entertain your maybe being there. It’d be real free-seeming, but incredibly lonely, he imagines.

Gately pities, more than envies, the wraith’s condition, because, per his description, it has a lot in common with the abject solitude of a figurant. The solution (writing, mobility, Identification) and the problem (voicelessness, immobility, loneliness) are not antipodes, but mirror images. So much for a straightforward endorsement of literary labor, on either end, production or reception.

To return, then, to the paradigmatic industry of Jim Struck, what the Endnote ultimately does, like the book as a whole, is to pose the question, so who’s really the wraith? Day’s article, wraith-like, has colonized Struck’s consciousness. But thus zombified, undead in a sense,[20] a model figurant, Struck himself adopts the stock-still pose and vocal cooption tactics of a wraith. And Struck’s predicament, buried in a seemingly inconsequential recess of the endnotes, becomes legitimately uncanny insofar as it anticipates our own. IJ doesn’t so much say as do something to readers: it turns us into figurants, which is to say that it also grants us the status of wraiths. And what is true of the reader is, as a corollary, true of the book: IJ, in Poulet’s sense, is a wraith, inhabiting us and extending the potential for Identification, and it is also a figurant, telling us nothing.

Read in this light, IJ might reflect Wallace’s discontent not just with consumer-capitalist addiction, but with a deep vein of aesthetic theory. Once upon a time, around the Baby Boom era, it was fashionable to excavate the paradoxes inherent in literary texts. With essays like “The Language of Paradox” and “The Heresy of Paraphrase” in The Well Wrought Urn, Cleanth Brooks argued that this structural principle—irony, contradiction, paradox—lies at the heart of all great works of literature.[21] And during the short-lived heyday of New Criticism, disciplined readers sought only to discover the pathways by which literary texts contrive their stony silences.[22]

In his journalistic writing, Wallace has weighed in, derisively, on the work of Brooks & Co.; he recounts, briefly in “Tense Present,” how subsequent waves of theory exposed the New Criticism as hermeneutic flimflam.[23] The essayist Wallace also decries irony as an intellectual pose, and figurant-class, say-nothing literature in particular. In “Fictional Futures,” discussing reportorial hipster fiction of a bygone era, Wallace calls out writers for describing problems without posing solutions, reducing, per Wallace, “interpretation to whining.” His big-picture verdict affirms his faith in revolutionary art: “What troubles me about the fact that Gold-Card-fear-and-trembling fiction just keeps coming is that, if the upheavals in popular, academic and intellectual life have left people with any long-cherished tradition intact, it seems as if it should be an abiding faith that the conscientious, talented, and lucky artist of any age retains the power to effect change.” Similarly, in “E Unibus Pluram,” Wallace tilts at irony,[24] imagining the cultural rebellion later dubbed the New Sincerity: “The next real literary ‘rebels’ in this country might well emerge as some weird bunch of ‘anti-rebels,’ born oglers who dare to back away from ironic watching, who have the childish gall actually to endorse single-entendre values.” All of the Tolstoyan energy in IJ reflects Wallace’s well-documented aversion to intellectual and spiritual nihilism.

But the self-negating turn in Infinite Jest, the turn that converts speakers into figurants, makes both of them wraiths, suggests that Wallace, in his greatest book, could embody but not transcend this artistic crisis. The novel virtually ratifies New Critical principles. What’s a Sierpinski gasket, after all, if not an incredibly well-wrought urn? Readers past and future, of all critical persuasions, figurant filmmakers included, might well balk at this conclusion, which has the dubious distinction of being both revelatory and obvious. But Wallace’s skepticism of art’s hermetic beauty? A gargantuan book wherein all the glinting particulars of an animate metropolis everywhere dissolve in these shadows of the valley of death? This without ever skimping in the effort to speak a score of deeply personal tongues? Plus just the writer’s resolve to stake a substantial chunk of his lifespan in the manufacture of an irksome and unrepeatable nothing? With this stuff I, for one, can like totally Identify.

—Bruce Stone

.

Bruce Stone is a Wisconsin native and graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts (MFA, 2002). In 2004, he served as the contributing editor for a good book on DG’s fiction, The Art of Desire (Oberon Press). His essays have appeared in Miranda, Nabokov Studies, Review of Contemporary Fiction and Salon. His fiction has appeared most recently in Straylight and Numéro Cinq. You can hear him talk about fiction writing at Straylight Magazine. He’s currently teaching writing at UCLA.

.

.

- The film’s release caused a minor flap in that the writer’s estate publicly announced its displeasure with the project, but the script deflects charges of foul play by airing Wallace’s anxieties about his celebrity and generally deferring comment on his work. Ponsoldt’s is a smart, bookish film hiding behind an idiot’s grin.†

† These endnotes obviously betoken a superficial solidarity with Wallace’s aesthetic. Roll your eyes all you want. Wallace himself learned the gambit from writers like Nabokov and Nicholson Baker, both of whom I prefer to DFW. But practical concerns persuaded me to fall back here: I wanted a nice deep root cellar in which to stash the worst of the spoilsport disclosures vis-à-vis the novel—someplace cool and spacious and dimly lit, with pacifying damp-clay smells and a large number of tappable casks, where the advanced group might repair for bonus tracks and outtakes. Then again, readers worried about spoilers would probably be well-advised to just click the topside X and duck out now.↵

- The house’s street address might read “The center of nothing,” Wheelchair Assassin Rémy Marathe’s garbled translation of “The middle of nowhere” in IJ.↵

- This is my conclusion even though I saw the film under snark-inducing circumstances: a primetime screening at a posh mall-theater on the expectably glammed Westside of Los Angeles. A wine bar next door absorbed some of the early-arrival foot traffic, and still the area around the high-tech ticket kiosks, where you can swipe your card to collect pre-purchases,† was crowded with affluent cineastes, awash in secondary sex traits (what with the women in LA prosecuting the sartorial arms-race of a desert climate). The screening chamber itself boasted notably luxurious, boxy faux-leather black recliners, like first-class airline seats that let you kick way back, outfitted with cupholders that could handle those absurdly large theater sodas, naturally. Even if you hadn’t finished IJ just weeks earlier, the signs of egregiously hedonistic spectation would have stood out in bold-face type.

Factor in now that the screening concluded with a Q&A involving Ponsoldt and Segel. Besides bumping up the general rate of crowd effervescence, the principals’ attendance also explains why greeters met filmgoers at the entrances and pressed upon them a sturdy bubble-sheet survey, with a tiny ballpoint, for the sake of audience feedback. Excepting one question about the draw of this particular film, the survey was all about purchasing behaviors, standard market research. I stood the form upright on the floor until the film’s end. When the lights came back on, Ponsoldt and Segel clambered into director’s chairs on the stage. They fielded deferential questions from a host, plus a few, later, from the audience, and though their handlers stood by at attention, overdressed, in the aisle, and though one young woman who had come solo—blond curls bestrewn in a Renaissance braid, simple sundress in a grayscale print—relocated after the credits rolled, the better to record on her smartphone the celebrities’ breathings, it was impossible to judge or resent anybody. Ponsoldt came off as a sweetly ingratiating fanboy (a little self-satisfied, but who can blame him?); Segel, a dapper mensch (yes, he claimed to have read the novel prior to filming; no, he didn’t understand it all that well; no, no one asked him to do the voice of Vector from Despicable Me). I stayed until the Q&A wrapped.

† I held up the queue as I fumbled around, like a true amateur or a bona fide Martian, with a confirmation-page print-out which the machine just sneered at.↵

- To be honest, the grief was probably as much about me—for me—as about or for Wallace.↵

- In my defense, circa 1996, I was in no condition to read IJ or care much about what the world made of Wallace. A brush with linguistic deconstruction, in grad school, left me more or less incapacitated, unfit for public consumption, much less civic participation, for the better part of two years. My pupils stayed dilated the whole time. The crushing irony, of course, is that I had gone to UW-Madison to study literature.↵

- Some of these exegeses are duly footnoted. Equally unsurprising is that many of them discuss the basic technics of reading: they note the heft of the book (which left a dimple like a check mark near my navel), the time spent per page (depends), the number of accessories required to cope with the acreage between main text and footnotes (I got by with a single pencil and a kind of clawed grip, involving the pinky, on the book’s spine).

For my own contribution to the genre, I seriously considered writing something first-personal, something between clear-eyed criticism and chronic self-absorption, about the ways in which IJ’s tactics anticipated with surprising regularity my own more daring plays as a fiction writer. Lots of little things, snatches of phrasing (anyone else borrowing the lingo from A Clockwork Orange?), architectural affinities (the tunnels at ETA vs. the tunnels at CU in my not-published novella), etc. Here’s just one substantial example, involving the special kind of unreliable narration in IJ’s first chapters. When Hal Incandenza attempts to speak to the admissions committee at Arizona, though his words, per his report, are calm and lucid, the deans hear only monstrous subhuman noises, accompanied by threatening behavior. The mutual distress is so severe that the deans pin Hal to the floor and have him committed.† In my own story “The Advantages of Living,” written circa 2005, the narrator likewise says apparently innocuous things that conceal a more outrageous reality. He gets his ass kicked, twice, deservedly, for his troubles.

I used this gambit again in “FPS,” clickable here in the magazine’s archives. That story also shares DFW’s appetite for tumbledown phrasing and deliberately tortured syntax (which he got from Pynchon, for anyone keeping score), but “FPS” really bears mention because that story is what propelled me into IJ last summer. Wallace, thinly disguised, has a cameo in “FPS,” his suicide plays a conspicuous role. The treatment might seem a bit glib and unfeeling, but something deadly serious lurks in the subtext, if you care to do a little math. My point being, Wallace and I shared some common acquaintances at Illinois State University—I actually applied, hilarious to me now, for his job when he vacated circa 2002 to take his post at Pomona—and as I was writing the story, his death came to seem less like a historical event and more like a loss in the extended family. This is what drove me, after two neglectful decades, to spend seven weeks or so under the hood of IJ.

Let’s acknowledge too that Wallace’s last words to Lipsky, in Ponsoldt’s film, were “You wouldn’t want to be me.” It would tie things together nicely if I were to think of the IJ synchronicity phenomenon in those terms, but I don’t. Instead, I was thinking that the strange correspondences between IJ and my meager stuff might make it possible to argue for the existence of a literary zeitgeist: that maybe world literature, if configured along certain traditional lines,‡ contained specific potentialities that amounted to almost a playbook of foregone conclusions for any reasonably ambitious young writer. I had planned to quote TS Eliot’s “Tradition and the Individual Talent” and Borges’ “Pierre Menard.” Decided wisely against all of this.

† My theory on Hal’s psychosis is that he’s not at all psychotic. Hal might, by the end of IJ, have experienced a transformation such that he’s no longer an emotionless figurant (see below), but is now for the first time fully human. He could be the poster boy for the kind of sincerity rebel that Wallace imagines at the end of his essay “E Unibus Pluram.” In a world of ubiquitous irony, where everyone is a figurant, such a rebel would have to be perceived as a monster; no one would recognize his utterances as speech because he would be speaking the foreign language of substance. (Notice too how the solution and the problem have identical symptoms.) The book makes this reasonably clear, almost obvious, but you have to splice some widely separated wires.

‡ Meaning the model that once prevailed in the undergraduate curriculum, in that transition moment between a hegemonic Western canon and all-out Canon Wars. For that matter, it’s not possible to talk adequately about IJ’s precursors without mentioning the filmmaker David Lynch.↵

- Here’s Bloom: “I don’t want to be offensive. But Infinite Jest is just awful. It seems ridiculous to have to say it. He can’t think, he can’t write. There’s no discernible talent…. Stephen King is Cervantes compared with David Foster Wallace.” And Ellis: “Anyone who finds David Foster Wallace a literary genius has got to be included in the, Literary Doucebag-Fools (sic) Pantheon.”↵

- Whether this ham-handedness is intentional, crucial to the book’s thematics, is a matter of debate. Some argue that such farcical touches show Wallace aping sympathetically the conventions of pulp entertainments. Others contend that such moments deliberately sabotage the reader’s pleasure, so as to distinguish Wallace’s novel from the lethal Entertainment of the same title. Wallace’s book might be the rumored anti-Entertainment, the narrative antidote to the film’s Medusa gaze.↵

- One filmic scholar even channels, pithily, Harold Bloom, specifically his more abstruse excrescences in The Anxiety of Influence: “For while clinamen and tessera strive to revive or revise the dead ancestor, and while kenosis and daemonization act to repress consciousness and memory of the dead ancestor, it is, finally, artistic askesis which represents the contest proper, the battle to the death with the loved dead.” Believe it or not, this bloated corpse of a sentence is more than empty blather: a meta-reflection on IJ’s literary ancestry.↵

- A Sierpinski gasket:

- See also the role, in IJ, of annular fusion, a closed-loop mode of power generation and waste disposal. The whole book can be conceived of as an annular, or ring-like, construct.↵

- Not all of which are easily resolved. In his discussion of the train-jousting ritual, Day mentions the miner’s son who loses his nerve and fails to jump across the tracks. His cowardice becomes legendary, widely known as “Faire un Bernard Wayne,” within the Wheelchair faction. The surname evokes a connection to John “N.R.” Wayne, ETA’s top player, himself likely a double- or triple-agent working for the Canadian terrorist cell. J. Wayne’s family hails from the same mining region in Quebec, but beyond this hint, the genealogical connection is impossible to lock down.↵

- This list of examples could go on and on. When Struck imagines Day “utterly strafed … and typing with his nose,” the contact between face and gizmo recalls JO Incandenza’s gruesome suicide (he sticks his head in the microwave) as well as the climax of the Eschaton game in which Otis Lord’s head gets lodged in a computer monitor. And dumb Struck’s plagiarism signifies a figurative voicelessness (see below), which evokes the text-recitation performance art of radio DJ Madame Psychosis, which evokes the literally muted Don Gately, intubated in the hospital, which evokes poor Lucien Antitois, impaled via the throat with his own hand-carved broomstick, which evokes Guillaume DuPlessis who dies of asphyxiation with a dust rag in his mouth, which evokes the catatonic “It” in her Raquel Welch mask…. My personal sense is that none of this is accidental, though all of it might be, for Wallace, Too Much Fun (see below).↵

- The density of the book’s interlacements actually reminds me of the mithril shirt, the Dwarvish chainmail from The Lord of the Rings. This reference to Tolkien isn’t entirely gratuitous. In a 1955 letter to WH Auden, Tolkien claimed to possess a kind of sixth sense: an ability to feel, palpably, the beauty of literary forms. “It has always been with me,” he writes, “the sensibility to linguistic pattern which affects me emotionally like colour or music.” I doubt that Tolkien would appreciate the intricate artifice in IJ, but this kind of extra-sensory perception, with a little recalibration, might help readers to experience the often stark, frequently disturbing, and sometimes downright ungainly IJ as something joyful.↵

- Note 304 confirms that the endnotes are inextricable from, rather than extraneous to, the novel’s artistic design. However, the endnotes, in aggregate, also point to a major glitch in said design’s matrix: namely, who’s writing them? It’s impossible to locate a central narrational perspective in IJ. The nominees include Hal Incandenza and a smattering of wraiths (JO Incandenza is the most likely choice, and Lucien Antitois’ death, a passing into knowledge of “all the world’s well-known tongues,” feels like a cue). But the wraith theory founders on the fact that Hal sometimes narrates from a first-person point of view; the Hal theory on the fact that he disappears for very long stretches of third-person limited narration.† Even if DFW himself were the implied narrator, the shifts into Hal’s first-person perspective don’t quite compute. This narrational evasiveness isn’t necessarily a defect in the novel.

† Perhaps the most jarring example of IJ’s narrational problem arrives as Don Gately speeds across town in the Ford Aventura. The prose tracks precisely with Gately’s perceptions and thought processes, until, inexplicably, we read, “Has anybody mentioned Gately’s head is square?”↵

- Identification strikes me as the gateway to the domain of reader-response criticism,† at one extreme pole of which even Struck’s plagiarism is fully licensed and authorized.

† I once read a student exam in which the writer said, of Frost’s “Stopping by Woods,” only that the poetic speaker reminded her of Santa Claus. A hard-core reader-response critic might argue that there is no such thing as better or worse in responses to literature, thus giving me no basis on which to judge negatively the student’s contention. While I admit that my initial reaction was to find the comparison ludicrous, I could be persuaded to play along—who knows, this reading might even be profound—provided that the student made the case with some kind of rigor, looking closely at and thinking hard about specific features of the poem and the legend.↵

- Zoran Kuzmanovich, in an essay on Nabokov’s “The Vane Sisters” (a famously haunted text), says something apropos: “Every ghost story is an allegory of reading.”↵

- Struck’s identification with Day’s article might be a travesty in that Struck isn’t really listening to the substance of the passage; Struck misses, for example, the kinship between the cult’s aspirants and the tennis hopefuls, himself included, at ETA.↵

- Poulet describes this tyranny of reading: “As soon as I replace my direct perception of reality by the words of a book, I deliver myself, bound hand and foot to the omnipotence of fiction. I say farewell to what is, in order to feign belief in what is not. I surround myself with fictitious beings; I become the prey of language. There is no escaping this takeover.”↵

- The novel has scads of references to the undead (vampires, revenants, wraiths, the living dead, etc.). One of my favorites is the nickname of Eugene “Fax” Fackelmann, a small-time criminal with a big-time role in the novel’s closing chapters: Count Faxula.↵

- Viktor Shklovsky, the godfather of Russian Formalism, after a survey of world literature even more exhaustive than Brooks’,† ultimately arrived at the same conclusion: that strategic juxtaposition—contradiction, irony, paradox, antithesis, ambiguity, a god with many names—is the common denominator in all forms of literary art. But owing to historical circumstances (mainly Soviet oppression), Shklovsky’s work remained virtually unknown until after New Criticism, and Shklovsky himself, had been laid to rest: call it a posthumous confirmation of findings.

†Brooks discusses poetry exclusively in The Well Wrought Urn, but Shklovsky observes the same design principles in novels, plays, fairy tales, even movies.↵

- Maybe an overstatement. In “The Heresy of Paraphrase,” Brooks labors to explain that poems might deliver some didactic statement, a declarative truth about the world, but he insists that such a statement, to be accurate, would be so fraught with qualifications as to cease to be an actionable proposition. His main contention is that the beauty and/or “meaning” of a poem lies in the interplay of its parts, not in any generic takeaway. Early in the essay, Brooks makes a distinction that proves especially relevant to the case of IJ: the formal juxtapositions in poems don’t cancel each other out like logical antitheses, but rather they constitute a unity, for Brooks an “achieved harmony.” Later, however, when Brooks discusses Keats’ “Ode on a Grecian Urn,” he talks about paradox in such a way that it approaches self-negation: “Keats’ Urn must express a life which is above life and its vicissitudes, but it must also bear witness to the fact that its life is not life at all but is a kind of death.” In its portrait of reading, IJ poses this kind of paradox, which nevertheless remains an “achieved harmony.”↵

- The demise of New Criticism is an old story, and reports of its death are often exaggerated.† Wallace concentrates on NC’s risible pretensions to scientific objectivity, “the stuff of jokes and shudders” for DFW.‡ But Wallace might be hasty to link NC, as he does, to Grammatical Descriptivism, whose executors sought to compile a dictionary in a bottom-up, vox-populi manner. As I see it, the real trouble with NC is that what starts as descriptivism comes out the other side as SNOOT prescriptivism, establishing a universal and maybe arbitrary standard for artistic creation/appreciation. NC tends to work best for an elite body of texts, not coincidentally produced in large numbers by White Male writers. Honestly, though, the politics bothers me less (as a White Male) than something even more basic: the suspicion that artistic principles, once apprehended and codified, are anathema to art itself. (Brooks & Co., in certain lights, seem to me like a kind of literary Penn & Teller act.) Maybe this fear is unfounded. What NC and its Formalist kin prescribe amounts to little more than a plea on behalf of structural unity, an imperative that form and content smartly bedevil each other. Still, the whole project risks devolving into mere routine, and a pall of cliché gathers ominously.† Fitting that Wallace, in IJ, should have harped on the need to recover the awful truth that underlies even the most moronic clichés.

† The close reading prescribed by NC continues to inform all responsible interpretive praxis (excepting Franco Moretti’s controversial “distant reading”), and this method survives too in creative writing programs, which work best when they emphasize craft and composition, not meaning (see, for example, Madison Smartt Bell’s Narrative Design, or even James Wood’s How Fiction Works). At present, NC is mounting something of a cultural comeback; in How to Do Things with Fictions (2012), Stanford’s Joshua Landy argues, once again, that literary works are defined by their structures and techniques, and that the best of these train readers to think in new ways.

When I read passages like this one, from Brooks’ “The Heresy of Paraphrase,” I find it hard to fathom how NC ever went so thoroughly out of style: “the word, as the poet uses it, has to be conceived of, not as a discrete particle of meaning, but as a potential of meaning, a nexus or cluster of meanings.” Another passage resonates with IJ in particular: “the ‘beauty’ of the poem … is the effect of a total pattern, and of a kind of pattern which can incorporate within itself items intrinsically beautiful or ugly, attractive or repulsive. Unless one asserts the primacy of pattern, a poem becomes merely a bouquet of intrinsically beautiful items.”

‡ Another objection is that the “unity” of literary works, prized by New Critics, is just a naïve fallacy, but to say that unity lends itself to a facile kind of deconstruction seems to me to substitute one truism for another. A related complaint, among gender-, class-, and race-minded critics, might be that no book is ever silent. You would have to take this up on a case-by-case basis, but see Note 22 above.

† NC, with its emphasis on pattern-making, might seem ill-suited to discussions of fiction, insofar as it elides less specialized measures of literary craftsmanship: matters of plot and characterization, suspense and transformation, climax and delay (aka, retardation)—all the vertices and dragons’ backs of the standard Freitag triangle (which was devised to explain dramatic design), to say nothing of style’s infinite permutations. However, NC’s principles operate there too, and even where they aren’t readily apparent, the same caveat applies. Writers might exaggerate or truncate the Freitag pattern of rising and falling action, make “inverted checkmark” structures of varying slope and acuity, rightside-up or upside-down, all day long, but they’re still bound by the model. For his part, Wallace tends to prefer the soft ending and anticlimax, among other “nonconfluential” tactics, in IJ (some exceptions include the Eschaton game and the fracas between Ennet House residents and Hawaiian shirt-clad ‘Nucks), but we can still think of the Sierpinski gasket’s interlocking triangles as a giddily Freitagian construct.

Which is to say, I get why some writers would want to take a hammer to convention, abjure every “literary” stratagem in the headlong pursuit of some asymptote of the real, a straighter record of what is. The rebellion has a long history, but David Shields, with his Reality Hunger manifesto, is the movement’s current poster child, and apparently the oral historian Svetlana Alexievich just bagged the Nobel Prize for her scrupulous suppression of artifice. Wallace understood this anti-aesthetic impulse, and its hazards, as well: in IJ, the filmography of JO Incandenza includes eleven works of “Found Drama,” some of which are “conceptually unfilmable,” none of which is released for viewing. Note that IJ is not itself a Found Novel.

Strangely, it would be possible to cite both Tolkien and Nietzsche (the philosopher’s dread becoming that smears the edges off of being) to allay these anxieties over artifice. Both writers hint at an upbeat conclusion: that the discovery of structural commonalities does nothing to exhaust the mystery and singularity of creation. You might as well resent having to write in English.↵

- Brooks himself finds the terms “irony” and “paradox” aggravating. He treats them as loose synonyms in “The Heresy of Paraphrase,” but Brooks’ “paradox” might be viewed as a remedy for Wallace’s debilitating “irony.” For further discussion.↵

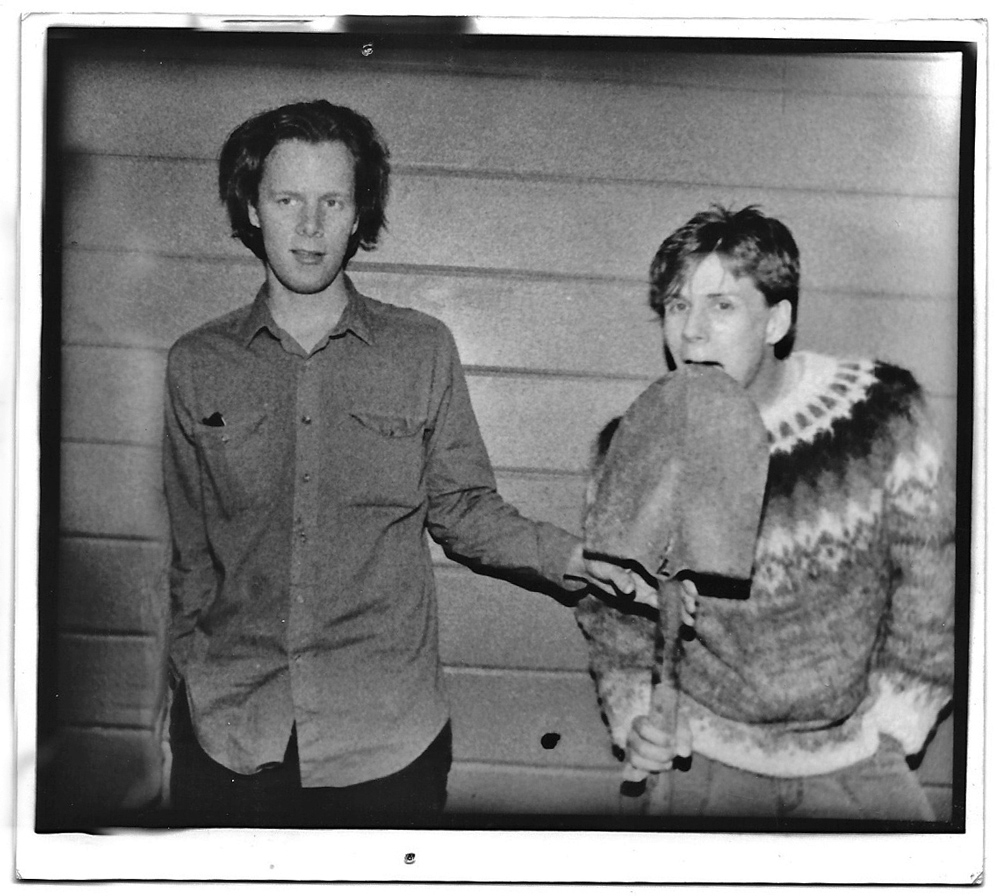

Michael and Kate

Michael and Kate

Shambhavi Roy

Shambhavi Roy

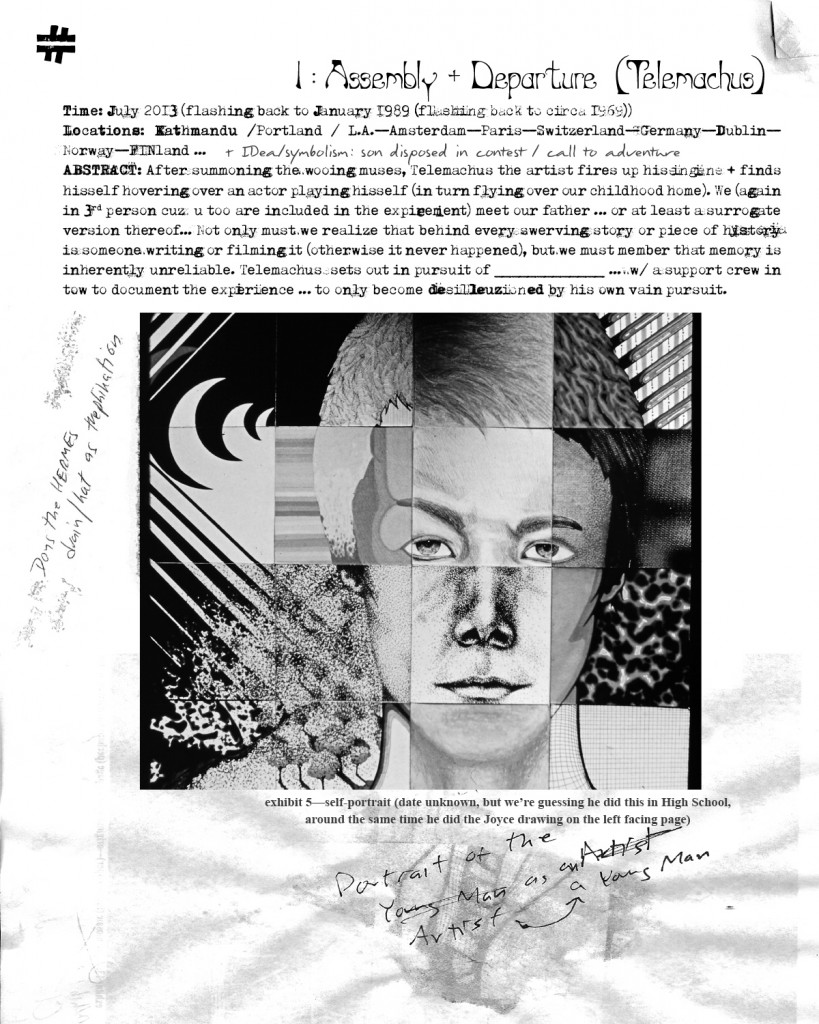

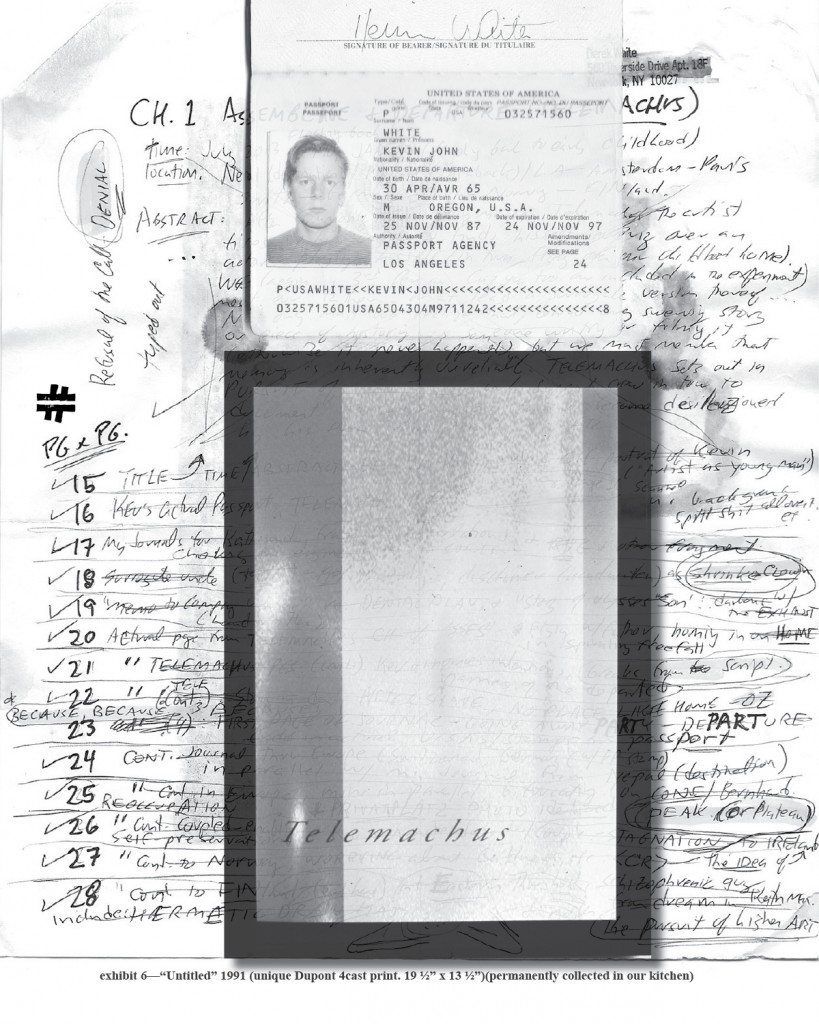

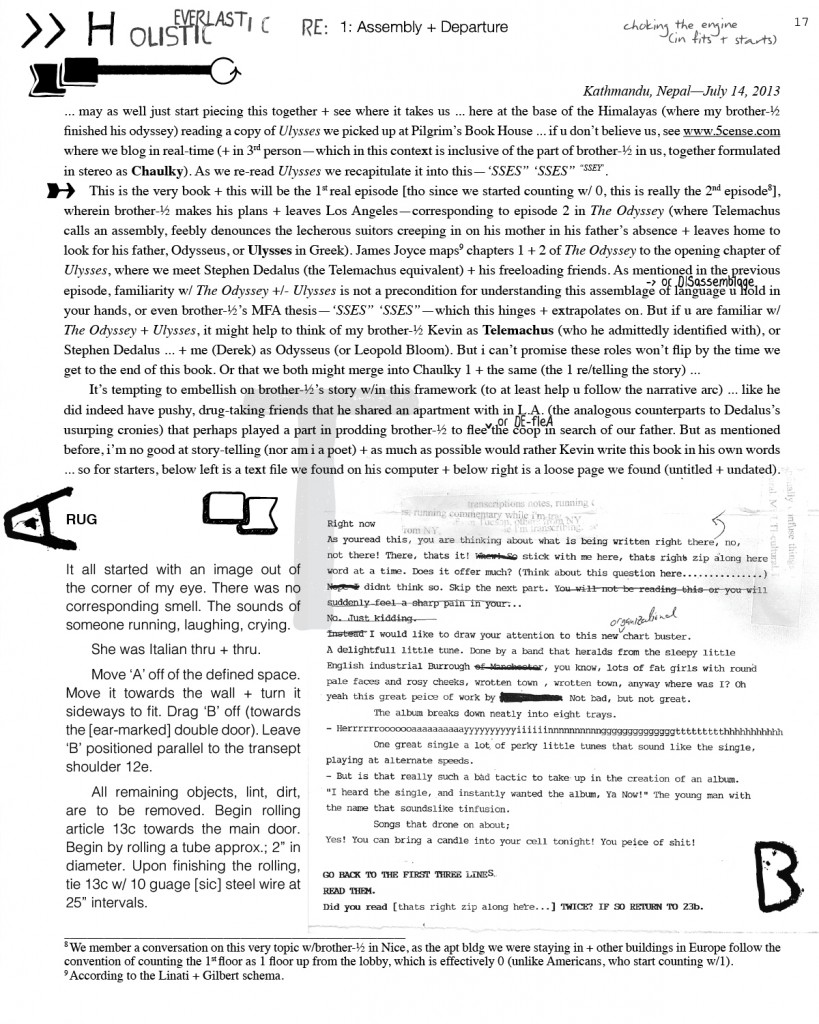

Chaulky White is the pen name given to the combined effort of

Chaulky White is the pen name given to the combined effort of

Oedipus and the Sphinx (detail) by Gustave Moreau

Oedipus and the Sphinx (detail) by Gustave Moreau Karin Fossum

Karin Fossum Jo Nesbø

Jo Nesbø

Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Noomi Rapace as Lisbeth Salander in The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo.

Lisa Moore

Lisa Moore

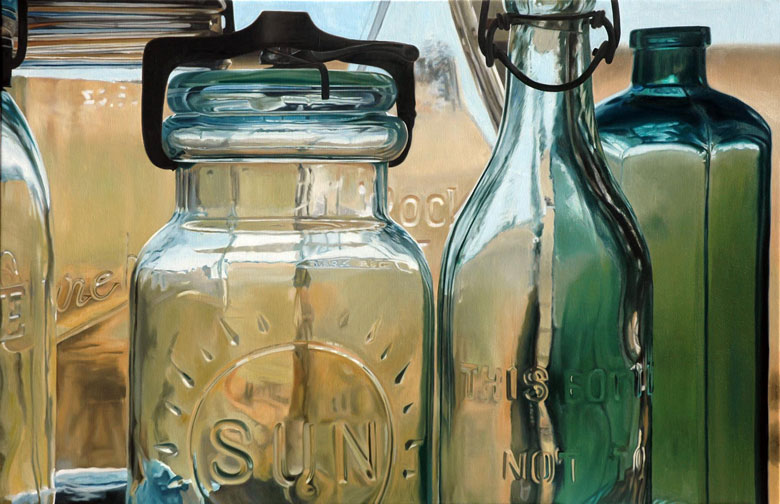

Figure 1. Steven Smulka. “Solar System.” 2011, Oil on Linen, 76.2 x 116.8 cm.

Figure 1. Steven Smulka. “Solar System.” 2011, Oil on Linen, 76.2 x 116.8 cm. Figure 2. Ralph Goings. “Double Ketchup.” 2006, Pigmented Inkjet on rag paper. 22×32.75 in. Edition of 30.

Figure 2. Ralph Goings. “Double Ketchup.” 2006, Pigmented Inkjet on rag paper. 22×32.75 in. Edition of 30. Figure 3. Randy Dudley. “Coney Island Creek at Corpse Ave.” 1988, Oil on Canvas. 28 1/2 x 54 in.

Figure 3. Randy Dudley. “Coney Island Creek at Corpse Ave.” 1988, Oil on Canvas. 28 1/2 x 54 in. Figure 4. Tjalf Sparnaay. “Vaatwasser” (“Dishwasher”). 1998, oil on canvas, 185 x125 cm.

Figure 4. Tjalf Sparnaay. “Vaatwasser” (“Dishwasher”). 1998, oil on canvas, 185 x125 cm. Figure 5. Tjalf Sparnaay. “Girl with a Pearl Earring in Plastic”. 2002, oil on canvas, 75 x 60 cm.

Figure 5. Tjalf Sparnaay. “Girl with a Pearl Earring in Plastic”. 2002, oil on canvas, 75 x 60 cm. Figure 6. Cynthia Poole. “Displaced Mints II.”2011. Acrylic on canvas. 100 x 120 cm.

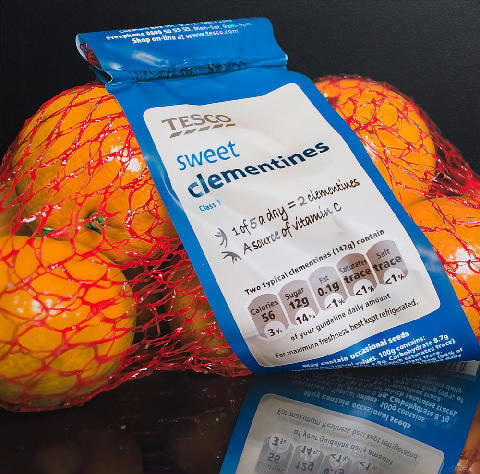

Figure 6. Cynthia Poole. “Displaced Mints II.”2011. Acrylic on canvas. 100 x 120 cm. Figure 7. Tom Martin. “One of Five.” 2009, Acrylic on panel, 90 x 90 cm.

Figure 7. Tom Martin. “One of Five.” 2009, Acrylic on panel, 90 x 90 cm.