An eagle swoops past a ship over Zolotoi Rog harbor. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

An eagle swoops past a ship over Zolotoi Rog harbor. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

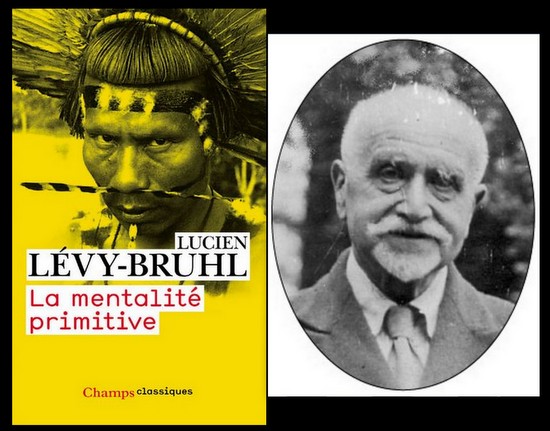

Nikolai Gogol couldn’t have written a better story than this, and this one is true: a Russian provincial governor, a lost fleet of ships, an illegal tiger skin, vainglory, murder, and the mob — Russell Working is a prize-winning fiction writer, a master wordsmith and a castiron reporter. For many years he lived in Vladivostok, running a small English language newspaper, falling in love, living in a frigid flat inhabited by the spirits of great Russian poets. He wasn’t “embedded”; he LIVED there. The result has been a recent spate of brilliant reportage (NC ran an earlier essay), or reportage crossed with memoir (or maybe it is a NEW FORM Russell invented). In Dead Souls, Gogol wrote the tale of a Dickensian con-artist who went around Russia buying up dead peasants that, by a book-keeping sleight-of-hand, he planned to mortgage off as live serfs. Gogol’s admirers said he had done nothing but tell the truth about Russia; Russell Working is doing the same.

dg

A MERCHANT. Such a governor there never was yet in the world, your Worship. No words can describe the injuries he inflicts upon us. He has taken the bread out of our mouths by quartering soldiers on us, so that you might as well put your neck in a noose. He doesn’t treat you as you deserve. He catches hold of your beard and says, “Oh, you Tartar!” Upon my word, if we had shown him any disrespect, but we obey all the laws and regulations. We don’t mind giving him what his wife and daughter need for their clothes, but no, that’s not enough. So help me God! He comes to our shop and takes whatever his eyes fall on. He sees a piece of cloth and says, “Oh, my friends, that’s a fine piece of goods. Take it to my house.” So we take it to his house. It will be almost forty yards.

KHLESTAKOV. Is it possible? My, what a swindler!

MERCHANTS. So help us God! No one remembers a governor like him.

—Nikolai Gogol

The Inspector General, Act IV, Scene 5

#

A Word to the Wise

Among the Lackeys of Foreigners

In the Fleet and the Media

Late one night in June 1999, a broadcast journalist named Yury Stepanov was walking home in Vladivostok, a Russian port city of six hundred fifty thousand on the Sea of Japan, when he came upon a Toyota minivan blocking his way up an alley. He hesitated. He was an editor at Radio Lemma, which had been receiving anonymous threats for reporting allegations of corruption and attempted extortion by the Primorye regional governor, Yevgeny Nazdratenko. But he had to get home, after all, and a cousin to hope, in the human mind, is the ability to convince oneself that all is well.

So he headed on between the van and the wall. A burly man in black emerged from the dark and smashed Stepanov in the face, knocking him to the ground. Another thug joined in the assault. They kicked and stomped Stepanov, head, ribs, gut. His assailants rolled open the door of the van and threw his briefcase inside. They tried to drag Stepanov in, too, he later said. He fought his way free and fled. His attackers chased him on foot all the way to his apartment building. They gave up when he flung himself through the doors. Perhaps it would have been a little too public, even for Vladivostok’s goodfellas, to kidnap an editor from the lobby of his apartment. Or maybe they figured their message had been delivered.

That week Stepanov holed up in his apartment, and this is where I found him a day or two later when I visited with Nonna, then my girlfriend and now my wife. She was a deputy editor at the Vladivostok News, a little English-language paper which I edited, and she often interpreted for me. We had gotten his address from his colleagues at Radio Lemma, but we had not called ahead. Probably he didn’t have a phone; many Russians never did get land lines, and this was before the era of ubiquitous cell phones. Or perhaps he simply was not answering, not wishing to subject himself to death threats. We headed up the filthy stairwell of his Soviet-era building, of concrete slab construction, and knocked at his door, a steel one, such as any sensible Russian lives behind. A blood-yellowed eye appeared in the peephole.

“Who is it?”

Nonna introduced herself and she had brought an Amerikansky zhurnalist to interview him. The blood eye blinked doubtfully, so I said in English, “Tell him I freelance for The New York Times and The South China Morning Post.”

Stepanov let us in to the bedroom/living room and bolted the latch behind us. His face was bruised purple and brown. He hobbled across the room and winced as he lowered himself to the futon and slumped over with a groan.

“How are you doing?” Nonna said.

“I’ve got three broken ribs, a concussion, too, the doctors said. It’s my family I’m worried about. I sent them out of town.”

Stepanov was not the only victim of mysterious circumstances at Radio Lemma. The day after Stepanov’s beating, a reporter glanced in the rear-view mirror and saw a truck accelerating toward his car. The truck rammed him, totaling the car. He was uninjured. Days later, strangers would snatch the nineteen-year-old daughter of another Radio Lemma editor from the street, take her on a little drive around the city, and warn her that her daddy had better tone down those broadcasts criticizing Governor Nazdratenko. “Tell you-know-who that if these statements continue on the radio, he’ll face the same thing that happened to his friend,” the men said. The friend they were referring to was Stepanov. After that they let her go.

Stepanov told us that Radio Lemma staffers had been living in fear ever since they had broadcast a series of reports about Vostoktransflot, the largest refrigerated shipping company in Russia, which was under pressure from the governor. Under the previous director, Viktor Ostapenko, Vostoktransflot had run up a debt of $96 million, the media reported. A pity, to be sure, but what could a chief executive do in a troubled business climate like Russia’s? Among Vostoktransflot’s creditors was the Bank of Scotland, which as lender effectively owned the MV Dubrava and eleven other vessels. To Ostapenko’s profound regret, he was unable to pay his employees’ salaries for nine to twelve months at a time. Understand, times were tough, and everyone on the team would just have row together and bite the bullet and give a hundred and ten percent and all that. Unpaid wages were commonplace in those days, and if Ostapenko was calculating that no one would mutiny over this, he knew his countrymen well. But then in August 1997, a young Moscow investor named Anatoly Milashevich, a graduate of Russia’s MIT—the Moscow Institute of Physics and Technology—obtained a majority share of Vostoktransflot, and the nation’s business climate magically improved overnight. This was clear because Milashevich began meeting the payroll every month. The next year, Vostoktransflot ran a profit of $10 million. By 1999 the company reportedly had paid off half its debts.

But business success is dangerous in Russia; dollars smell like blood. Or this is more or less what Vostoktransflot’s leadership team discovered. Nazdratenko summoned Milashevich to the regional administration building known as the White House and, the young executive alleged, demanded a $2 million “campaign contribution,” or else. Milashevich went public with what he claimed was an extortion attempt. It so happened that the day before Stepanov’s beating, Radio Lemma had broadcast a live interview with Milashevich.

Nazdratenko (right) offers flowers to veterans in Vladivostok. Photo by Yuri Maltsev

Nazdratenko (right) offers flowers to veterans in Vladivostok. Photo by Yuri Maltsev

The governor denied he had bullied or threatened Milashevich or sought any bribes. By God, he was just protecting Russia’s fleet from nefarious foreigners and their Russian hirelings. The regional media, mostly controlled by Nazdratenko, launched a propaganda campaign against Milashevich. The governor had other levers to pull, as well. Under pressure from the White House, a district court ruled that Milashevich had gained control of Vostoktransflot illegally, and a judge replaced him with a man more to Nazdratenko’s liking, one whose extensive experience in refrigerated shipping made him an ideal pick to lead the troubled company. He was Viktor Ostapenko, the very man who had sailed Vostoktransflot onto a reef and run up that $96 million debt.

Bailiffs accompanied by a police SWAT team of masked gunmen stormed Vostoktransflot’s office, evicted Milashevich’s staff, and installed the new management team. When the new team opened the safe, with great excitement, they found nothing but a bottle of Chateau de la Tour red and a note that Milashevich had left for them (“Gentlemen, help yourselves”), he recently told me in an e-mail. Milashevich and his team fled to Cyprus.

This spring I exchanged a number of e-mails with Milashevich, but I never caught up with him for an interview. He noted that the Vostoktransflot case was not isolated, but acted as an “archetype” for government actions against business nationwide. “Our history was a drop of water that reflected trends that were happening in this country later (with Yukos, etc.),” he wrote, referring to the company that the Russian government crushed in a tax case, sending its chief executive, Mikhail Khodorkovsky, to prison. Critics of President Vladimir Putin suggested the case against Yukos was politically motivated, as Khodorkovsky had funded opposition political parties.

Once he was in charge, Ostapenko issued a worldwide order demanding that the entire fleet of thirty-eight ships return to Vladivostok, never mind their contract obligations or cargo they were carrying or their position on the earth. Oh, and good news: Ostapenko now discovered that it was possible, after all, to meet payroll. Puzzlingly, only four ships obeyed. One of those that did respond was the ship Ulbansky Zaliv. Over a year later, the crew was still owed $300,000 in wages despite a court order to sell off three Vostoktransflot ships to cover the debt to their sailors, and the crew of were Ulbansky Zaliv was left to issue threats that they would flood the fuel tanks with seawater and scuttle the ship by the pier of Vladivostok’s fishing port if they were not paid.

The prow of Ulbansky Zaliv. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

The prow of Ulbansky Zaliv. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

Unpaid sailors from the ship Ulbansky Zaliv at a meeting in which they announce they will sink their ship in port if they aren’t paid. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

Unpaid sailors from the ship Ulbansky Zaliv at a meeting in which they announce they will sink their ship in port if they aren’t paid. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

The rest of the captains continued to answer to Milashevich, who was communicating with them from Cyprus by radio. On July 2, Milashevich’s team sent Captain Igor Tkachenko to Calcutta to sell the ship, Titovsk, for scrap, because it was obsolete and did not meet company standards, Tkachenko later told the media. Ostapenko began sending radiograms every seven hours demanding that Tkachenko break the ship’s contract and carry out another job more to Ostapenko’s liking. One message stated, “You are hijacking the ship together with the crew, a violation of Article 211 of the Russian Criminal Code … Are you thinking about what you are doing?” Alarmed and confused by the turmoil, Tkachenko ignored the messages and kept sailing. “They were absurd,” he said in a later press conference quoted by The Moscow Times. “Can you imagine how I felt about that message on a stormy sea?” Once Titovsk arrived in Calcutta, the deal was delayed a month because Ostapenko’s team began telegramming the Russian consulate demanding that officials intervene.

Now it was time for Vladivostok Mayor Yury Kopylov, a Nazdratenko appointee and ally, to turn up the heat. He ordered Radio Lemma to stop interviewing his and Nazdratenko’s political foes in what was an election year, the journalists said. “I hope that you guys are smart enough, and that no physical actions will follow,” Kopylov reportedly told them. A spokeswoman for Kopylov denied that he had threatened them, adding that he had nothing to do with Stepanov’s beating. Indeed, she found the editor’s claim of an assault “suspicious.” Since when had any journalist ever suffered for defying the authorities in Russia?

§

Curiously, while staffers at Radio Lemma were afraid for their lives, we at the Vladivostok News operated with an editorial freedom the rest of the local media, including our Russian-language parent paper, the daily Vladivostok, could only envy. Our print edition had died with the 1998 ruble crisis, and we now published on the Internet only. It would not have taken anything as crude as a beating to deal with me, had anyone cared. I could have been denied a visa or threatened and chased out of the country. But that never happened. The publisher of our parent paper, who had shown courage during the attempted coup d’état against Gorbachev in 1991, was by now allied with Nazdratenko; this made the Vladivostok News’ editorial independence all the more surprising. I suspect this was only because neither our publisher nor anybody else who mattered could read English. The point is, it took no courage whatsoever for me to publish stories that contradicted Nazdratenko’s official line. For my Russian staff, Nonna included, it was a different story. Had the governor’s White House woken up to what we were writing, they could have been subject to the Radio Lemma treatment.

The federal authorities also left us alone. In 1995 an agent from the FSB—the successor to the KGB—had become curious about the small group of Russians and foreigners who were putting out an English-language newspaper in town. He phoned Nonna in the newsroom and told her to come downstairs immediately and meet him outside. A tired-looking agent in his late thirties was waiting in a shabby Russian car, although anybody of means in the Far East drove a Japanese import. His familiarity with her biography frightened her a little. He knew all about her time dancing in a contemporary troupe, her past work as a translator for the Oceanographic Institute. He wanted to know what all those foreigners were up to in town.

“Why don’t you come up and ask them?” Nonna said.

“No! You never talked to me. This is just between us. That’s an order.”

But when he sent her back upstairs, Nonna immediately told everyone about her conversation with the FSB agent.

Only one article I wrote, a freelance piece for The New York Times on another firm, Far Eastern Shipping Co., ever drew any reaction from the local authorities. I can only speculate that this story must have been translated by the Russian Foreign Ministry and found its way to the regional White House; surely nobody in the Nazdratenko administration was paging through The Times or reading it online in English. A few weeks after the beating of Stepanov, Natalya Vstovskaya, the governor’s press secretary, phoned our parent paper and asked the editors to print a letter. The White House would pay the usual rate, she said. Russian newspapers often accept cash to print official statements disguised as letters or news stories, and the governor wanted this one to play prominently. It had not yet been decided who would sign it, but Vstovskaya would supply a name.

Fine, fax it on over, she was told.

By the time the letter arrived, someone had scrawled a name at the bottom: Yury Ukhov, chairman of the Far Eastern Shipping Company Trade Union. This was a typical Soviet-era practice: using a mouthpiece with working class bona fides to issue a denunciation on behalf of the Party. Oddly, the publisher declined the opportunity to make a buck off an advertorial attacking an employee, and the White House went trolling elsewhere for a venue for its letter.

A few days later the letter ran in a tabloid called Novosti. Ukhov (or his ghostwriter in the governor’s office) expressed indignation over my story for The New York Times. He called me “illiterate and dumb” and warned of the “boundless evil” of foreign provocateurs such as me. “What a beast Governor Yevgeny Nazdratenko is!” the letter stated sarcastically, implying that I had written this. Ukhov, who apparently did not realize I lived in Vladivostok, wrote that I was one of these foreigners who think that Russians still wear velveteen trousers and sleep on stoves in the fashion of peasants of old. It compared foreign investment in the fleet to stealing a cucumber out of someone’s garden. (The quotes I have are preserved in a column I wrote for The Moscow Times. The full letter appears to have melted into the sands of the Internet.)

Even if we had not known that the letter originated in the White House, it would have seemed unlikely that that Ukhov was a regular reader of The New York Times. I asked Nonna to telephone him and subtly sound him out on this (Gosh, that’s great that you read English; where did you study?). But she was filled with righteous indignation on behalf of her man, and, judging from the side of the phone conversation I overheard, it turned into an argument. She hung up.

“Well?” I said.

“He told me, ‘I am ashamed that you, a Russian woman, are defending foreigners.’”

§

Nazdratenko views mock-ups of the next day’s paper in the newsroom of Vladivostok. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

Nazdratenko views mock-ups of the next day’s paper in the newsroom of Vladivostok. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

Once, Nonna and I had the opportunity to ask Nazdratenko directly about some of the turmoil at Vostoktransflot. Around that time he dropped in on the newsroom of the Vladivostok to take questions, and Nonna and I invited ourselves upstairs. The newsroom was like any other—crowds of desks, computer terminals, heaps of faxed press releases—except that an old bust of Stalin occupied a shelf near the door. (The journalists considered this a joke.) The governor was a fleshy middle-aged man with a five-o’clock shadow and permanent sheen of sweat, and the publisher ushered him to a comfortable seat. Nazdratenko was relaxed, accustomed as he was to fawning coverage. He tended to refer to crowds as “my friends,” and, in the condescending manner of communist bureaucrats, addressed young women reporters as “ty”—the informal you. The journalists crowded around, and everyone lobbed questions at Nazdratenko, who amiably swatted them into the bleachers. Who wouldn’t enjoy this? Local TV stations devoted their entire hour-long newscasts to his daily schedule, trumpeting the governor’s ribbon-cuttings and handshakes with visiting officials. When he held press conferences, his spokeswoman distributed printouts listing the questions he wished to be asked. Reporters compliantly raised their hands and asked. Even editors said they felt compelled to attend the governor’s press conferences, although they had reporters in the room to cover the events. “Someone might notice if I don’t show up,” one editor said.

But at one point as he droned on, I whispered in Nonna’s ear: “Ask him about Milashevich and the $2 million.” When Nazdratenko paused, eyebrows raised, awaiting another softball, Nonna fired the question.

The governor purpled, and his nostrils flared. The publisher’s mouth fell open. Reporters stared at us in surprise. “Did you [ty] ask that question yourself, or did your friend put you up to it?” the governor asked Nonna, nodding at me.

Characteristically, Nonna said, “I myself” (ya sama).

“Sama, sama!” Nazdratenko muttered scornfully.

He then angrily denied the allegation and reiterated his contempt for foreigners and their hireling Milashevich. “I wouldn’t accept a postcard from that company.”

He looked around to indicate he was open to a more appropriate line of inquiry. Andrei Ivlev stood up, a bony-elbowed, thirties-ish senior editor in a suit coat that hung on a frame like a dry cleaner’s coat hanger, and, with a glance of solidarity at Nonna and me, he nervously sang out a confrontational question that made the publisher flinch. I can no longer remember what he asked, but he could have been dealt with Radio Lemma-style. Nazdratenko growled a reply and looked at the publisher as if to say, This will not be forgotten. Other tough questions followed. But this moment of editorial fortitude did little good. Nothing that contradicted the governor’s narrative made it into the paper the next day.

Around that time, an item appeared in the newspaper Utro Rossii. A spokesman for the governor’s office invited editors to attend a critique of their coverage of Vostoktransflot. As the paper noted, “the editors of the newspapers were urged to fire journalists who give the wrong point of view of events.” And when Nazdratenko’s birthday rolled around, members of the media threw him a party. They gave him a dartboard decorated with the face of a political foe. And they sang a song they had composed, referring to him, in the formal Russian manner, by his first name and patronymic:

Yevgeny Ivanovich, molodets;

Oppozitsiyi prishol konets.

Which means:

Yevgeny Ivanovich, attaboy;

The opposition has been destroyed.

§

Himself

Governor Yevgeny Ivanovich Nazdratenko reportedly was born February 16, 1949, aboard a ship that was evacuating one of the Kuril Islands, a chain whose southernmost outcroppings Russia and the Soviet Union have possessed since World War II but Japan also claims. According to the website Komprinfo.ru, islanders were warned a tsunami was approaching, and they fled to sea, where the wave would ripple harmlessly beneath them. I have been to the remote islands, and the story raises questions in my mind. Did thousands of islanders really have enough notice, in the hours it takes a tsunami to sweep across the North Pacific, to round up the kids, drive over the island’s unpaved roads to the port, take a motor launch out to a ship anchored in the harbor, and clamber one-by-one up a gangway to the deck before steaming to safety? Nazdratenko’s mother is said to have come from a family of former Gulag prisoners, but this should not be taken to mean they were dissidents. Even if the story is true, Nazdratenko’s family could have been anything from common criminals—the elite of Stalin’s slave labor camps—to innocent citizens denounced by envious neighbors in search of a better apartment. Nazdratenko’s mother reportedly divorced his hard-drinking father when the future governor was a child.

Romantically, Nazdratenko is said to have met his future wife, Galina, as a child, although Komprinfo.ru does not detail the circumstances; the Web site does state that the future governor attended a music school, where he mastered the accordion. He served in the Navy as a welder, graduated from the Far Eastern Technological Institute, and eventually rose to “helm” (as The Wall Street Journal likes to put it) a mining company. In time he became a member of the Russian Duma, and was elected governor in 1995. Since taking office, he had accomplished the feat of impoverishing a region rich in natural resources at the crossroads of the booming economies of Japan, South Korea, and China. Nazdratenko did excel at collecting personal rewards and medals. When Patriarch Alexii II visited Vladivostok, the holy leader of the Russian Orthodox Church cited Nazdratenko’s “great service to the people” and honored him with the Order of St. Daniil Moskovskii.

Governors serve a different role in Russia than they do in the West. In the U.S., the states form separate power centers with taxing and enforcement structures independent of Washington. But in Russia, governors are part of a pyramid of authority with the Kremlin at its peak. For most of the nation’s history, they were appointed by Moscow, rather than elected, although Nazdratenko did win his office in a popular poll. Putin would scrap the election of governors in 2004, then reintroduce the vote following protests in 2012. A few months later he signed a law rendering the reform meaningless by allowing him to pick regional leaders if local lawmakers overturned the polls. The governor controls the police and distributes funding from Moscow to the cities. This allowed Nazdratenko to starve the Vladivostok administration of cash when he clashed with the city’s eccentric former mayor, Viktor Cherepkov. Nazdratenko eventually forced him from office.

It says something when the chief hope for reform lay in the FSB—the former KGB whose agent had summoned Nonna to his car. In 1997 President Yeltsin appointed General Viktor Kondratov, head of the local FSB office, as his representative to Primorye. Yeltsin was said to be sick of the constant reports from the Russian Far East of corruption, blackouts, unpaid wages due to theft by higher-ups, and other misery, and it was rumored that Nazdratenko would not survive much longer in office. Kondratov’s agents raided Nazdratenko’s White House in a case that brings to mind the U.S. Attorney’s Office swooping in on a corrupt Illinois governor. FSB agents lugged out computers and floppies and boxes of documents, and had this been the Northern District of Illinois, grand jury indictments would have followed. But in Russia, governors are immune to prosecution, so Kondratov focused on those around Nazdratenko, hoping the pressure would push the governor from office.

I first met Kondratov shortly after the raid, when we learned he was holding a press briefing at the FSB headquarters. Nonna and I showed up at a lobby decorated with a bust of Felix Dzerzhinsky, a Polish revolutionary who headed the FSB’s predecessor, the Cheka, at a time when it was notorious for torture and summary executions.

We tried to get in, but the public affairs officer told us, “We’re not having a press conference. Who told you that?”

“The Mayor’s Office,” Nonna said.

“Well, it’s not true. Besides, the general’s office is very small. He can’t fit many reporters in at once.”

Nonna is nothing if not persistent, and she phoned Kondratov from the lobby. We were invited on up.

An FSB agent escorted us upstairs to an office where, yes, reporters had indeed gathered. The burly general kept a set of barbells to work out with (he also liked to swim in the sea), and in a later story on Vladivostok’s loony politics, The New York Times’ Michael R. Gordon would describe him thus: “Dressed impeccably in a suit and tie and carrying an unlit pipe, Mr. Kondratov looks like a suave character out of a John le Carré novel.” By Kondratov’s account, he was present at a 1982 meeting when Communist Party First Secretary Yury Andropov, a former KGB chief, announced a twenty-year plan to liberalize the economy; thus Kondratov makes the astonishing claim that it was the KGB that set the Soviet Union on the path to democracy. Still, Kondratov was not always above reproach. After the police searched his allegedly drunken and belligerent son-in-law during a raid on a night club, the two officers involved were fired, the media reported. Many papers suggested Kondratov played a role in this, a charge he denied.

As I pulled up a chair, his gaze settled on one of my ears.

“What’s that?”

“A hearing aid. I’m hard of hearing.”

“American spy,” the general muttered with a wry tilt of the eyebrow. The other reporters chuckled. “But we have become friends now, haven’t we?”

Kondratov summarized a report the FSB had compiled for President Yeltsin’s office. Later leaked, the document, dated June 19, 1997, accused Nazdratenko of working hand-in-glove with the Mafia to muscle the economy of Primorye. His sons allegedly used bribery and force to wrest control of fuel, alcohol, and casino businesses in the region, and to smuggle contraband through the region’s ports. The FSB documented allegations that Nazdratenko’s son, Andrei, had gained control of Chechen gangs in the border city of Khasan, streamlining the smuggling of narcotics, rare metals, and sea urchins, which are considered luxuries in China and Japan. The FSB stated:

On the governor’s initiative, people were appointed to the main posts who used their work in the power structure of Primorye to strengthen their influence on the economy for the purpose of personal enrichment. These bureaucratic bosses empower corrupt interests with the aid of law enforcement agencies and leaders of organized crime.

In other words, the bureaucrats and the goodfellas were all in it together. It was an association Nazdratenko himself once hinted at in an interview with the newspaper Izvestia. “Indeed, I have appealed to the criminal world,” Nazdratenko said, in an interview quoted by The Chicago Tribune, “and many of those whom I asked for collaboration are wearing tuxedos rather than leather jackets for the first time,” as if the emergence of godfathers in dinner jackets with shiny lapels were not a tacky throwback to Capone and the Corleones, but an unprecedented and favorable development of his administration.

First Vice Governor Konstantin Toltoshein, accused of mob connections and kidnapping a reporter, promotes a book on Nazdratenko. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

First Vice Governor Konstantin Toltoshein, accused of mob connections and kidnapping a reporter, promotes a book on Nazdratenko. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

Most U.S. states somehow get by with a chief executive and a single lieutenant governor, no doubt toiling to exhaustion, but Nazdratenko distributed the workload among thirteen vice governors. These sub-bosses forged alliances with the mob to further their interests, the FSB alleged. The most noteworthy of them was First Vice Gov. Konstantin Tolstoshein, a weak-chinned, beak-nosed man who perpetually wore a parrot’s expression of fanatical perplexity. I once encountered him on the edge of a protest outside the White House—workers demanding unpaid wages, if I recall correctly—and through Nonna I asked a neutral question along the lines of, “What do you make of all this?” An American politician would slap you on the shoulder and say, “Hey, how you doin’, great question,” and then blame the previous administration for the problem, and assure you that he and the governor were fighting every day for working men and women, and, by God, they wouldn’t rest until every penny of back wages was paid. And he would have cited statistics proving that problem was receding under the current administration, or argued that his opponents had reached a new low in politicizing this human tragedy. But Tolstoshein looked as if I had stuck a ruler between the bars of his birdcage and rapped him on the head. He began shouting obscenities. When I tried to interject, “I don’t understand why—,” his voice rose to a shriek, and I was instructed in rich new forms of Russian poetics. Nonna tugged on my sleeve, and we retreated.

Now Kondratov was alleging that Tolstoshein had seized control of numerous companies in the region, setting up his adult daughter and mother-in-law as puppet executives. “Tolstoshein,” the FSB stated, “uses connections with the leaders of criminal groups for violent actions toward competitors.” The report noted a notorious incident from 1994, when Tolstoshein had been mayor of Vladivostok. After VBC Radio broadcast an assessment of Tolstoshein’s first hundred days in office which he didn’t like, he phoned the station, “screaming obscenities and demanding apologies,” the newspaper Kommersant reported. The radio station hastily climbed down and offered its regrets, both on air and in print. But that was not good enough for Tolstoshein’s pals, who keenly felt the mayor’s pain. The radio station’s commercial director took VBC reporters Alexei Sadykov and Andrei Zhuravlyov on a little drive to a city stadium, supposedly to tell Tolstoshein in person they were sorry, for his feelings really were hurt. For God’s sake, he was probably sulking in his cage, plucking out his feathers in a rage, refusing to do any more goddamned mayoring until he received further apologies, and where would that leave the city, eh? Unmayored, that’s right. From the stadium, the mobsters (the crime boss A.B. Makarenko was involved, the FSB alleged) then drove Sadykov to a cemetery and helped him see how unfair he had been. Tolstoshein was a great guy, and in case Sadykov forgot it, here was proof. The mobsters put a sack over his head, beat him, and tortured him with cigarettes.

Kommersant added, “They forced him to dictate on a tape recorder that he received a bribe of $100 from the ousted [Mayor] Victor Cherepkov.” Which of course settled the matter.

When he escaped with his cigarette-pocked skin, Sadykov filed criminal charges. But his own station’s commercial director was merely reprimanded, and nobody went to jail.

Three years after the alleged kidnapping, but before the FSB report that raised the same charges, we pursued the story at the Vladivostok News. I admired the guts of our interpreter (and later reporter), Anatoly Medetsky. He phoned Tolstoshein’s secretary on my behalf and asked to arrange an interview for me with the first vice governor. Why? Well, I wanted to know whether Tolstoshein did or did not order the kidnapping and torture. Told that the first vice governor was unavailable, Anatoly bravely left a message. Tolstoshein never called back. Maybe we lucked out.

As for all the evidence the feared FSB accumulated, Kondratov filed forty-two criminal cases. The local courts, under the control of Nazdratenko, refused to consider them. And that was that.

§

The Baron and the Sex Ambulance Tycoon

Since the time of Gogol, the character of the governor has periodically appeared in Russian literature. In The Inspector General, Governor Anton Skvoznik-Dmukhanovsky extorts bribes and flogs a corporal’s widow so severely she cannot sit for two days, although she gets off lightly compared to the prisoners in Dostoevsky’s Notes from the House of the Dead, who are sentenced to a thousand strokes, two thousand, the beatings distributed in tranches, between which the inmate is hospitalized, nursed back from the shadowland at the border of life, and then flogged another thousand times, often to death. On the remote Pacific island of Sakhalin, a former penal colony, Governor-General Baron Korf told Chekhov, who visited in 1890, that the prisoners there lived better than their fellows anywhere else in Russia or Europe, never mind that Dr. Chekhov was tormented one night by the cries of inmates in the prison next door, begging for admission to the hospital. The next morning he glimpsed the sick, mud-soaked men, and he concluded that “I saw before me the extreme limitations of man’s degradation, lower than which he cannot go.” For his part, Tolstoy offers us Count Fyodor Rostopchin in War and Peace. Terrified of a mob that gathers outside his palace during the French invasion, he hands over a prisoner as a scapegoat, to be torn to pieces. “Lads!” Rostopchin cries. “This man, Vereshchagin, is the scoundrel by whose doing Moscow is perishing.” But only one governor in Russian history, as far as I know, has ever won a prize from a secretive society of noblemen who serve their fellow man by giving away cash to super-rich actors and politicians.

It happened like this. One day late in 1998, amid daily blackouts and a heating crisis that left water freezing in the toilets of thousands of apartments across the Russian Far East as temperatures plunged to minus 49 Fahrenheit, the White House announced news it seemed confident would cheer its grumpy citizenry. The World Aristocratic Academy, an association whose address was a post office box in the Bahamas, had awarded Nazdratenko a million-dollar prize as Aristocratic Governor of the Year, the White House reported. The Academy was said to be headed by a certain Baron De Caen and included a Baron de Rothschild, Duke Kemberinsky, Prince Golitsyn (presumably a descendant of the great Russian statesman of the seventeenth century), and “other prominent representatives of aristocratic families.” The academy wished to honor Nazdratenko “for his incorruptible sincerity, principles, and aristocratic manners in defending his opinion,” the White House stated. The members of the academy apparently had never sat in on a press conference in which Nazdratenko blew his stack at a question, but never mind. He would now be honored, we were told, alongside King Juan Carlos of Spain (“Aristocratic King of the Year”), New York Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (topping the “aristocratic mayor” category), the Russian boy band Na Na (surely you’ve heard of them), actors Demi Moore (star of the movie “Striptease”) and Harrison Ford (revered for his cardboard portrayals of righteously angry men in a scrape), and Princess Diana of Wales (a posthumous winner). Six million dollars would have bought a lot of polio vaccinations in Afghanistan, but, blimey, think of the trickle-down effect if we give it all to the rich and famous: this must have been the philanthropic academy’s logic.

The source of these tidings, the White House reported, was a hospital procurer and White House confidant named Viktor Fersht, previously known for his failed effort to establish a “sex ambulance” for men in urgent need of physical congress. Fersht claimed to be a graduate of the New York-based University of International Education, an organization whose existence I was unable to confirm. His résumé was filled with impressive flourishes. Fersht said he represented Primorye to the United Nations, a claim that might have surprised the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. He also made known that he was “director of medical intelligence” for an organization that treated wounded “veterans of espionage,” presumably providing care for all those secret agents who are injured every year in James Bond-style shootouts with their American counterparts. Fersht would soon procure further fame when he announced that a meteorite that had hit Primorye decades ago prevented erectile dysfunction and helped smooth facial wrinkles. Overnight, enterprising healers began selling chunks of blackened iron ore in Vladivostok’s street markets.

So which of Nazdratenko’s noble qualities had led the World Aristocratic Academy to honor him? When I called the Bahamas, a receptionist for the lawyer who had incorporated the academy refused to reveal the names of any officers or put me in touch with a spokesman. It was left to Fersht to explain. He said the award came about after a chance meeting he had with Baron De Caen in the Bahamas. Devil knows, as the Russians say: perhaps after a gratifying tour around Nassau in an ambulance, sirens blaring, the French nobleman in Bermuda shorts settled at a swimming pool bar beside the secret agent health sector executive, where they both sipped Mai Tais from water coconuts and twirled their little cocktail umbrellas. Whatever the setting, Fersht said he described Nazdratenko’s noble attributes, and the Frenchman must have been moved. For the next thing you know, His Liege was writing out a million-dollar check to an obscure Russian satrap in a region plagued by accusations of official thievery, assaults on the free press, and Mafia connections at the highest levels. Or this is more or less the tale citizens were asked to swallow.

Curiously, Primoryeans did not celebrate Fersht’s news with fireworks, spontaneous mazurkas, or smooches to the lips of pretty girls on downtown boulevards. The award was too much to swallow even for those papers on the governor’s payroll, and the news was covered skeptically. Never mind that the money to buy coal for the region’s power plants had evaporated, that fractals of frost were blossoming on the walls of our apartments; all Russians could take pride in Nazdratenko, Fersht insisted. In an act of noblesse oblige, Nazdratenko announced that he would donate his entire million bucks to the poor. The Primorye Red Cross promised to partner with the governor to give away food packages, and leading Western businessmen and international aid groups were recruited to serve on the board of an umbrella organization that would distribute His Worship’s largesse.

No good deed goes unpunished, as they say, and sure enough, certain types sneered at the reports of aristocratic jackpots. Foreigners, cynics, political foes—unsavory, all. I phoned a Giuliani spokeswoman in New York, who told me, “Quoted: Mayor’s press secretary says, ‘No way.’ We’ve never heard of this group.” The Princess of Wales’ former spokesman and her charitable foundation had no record of any windfall from societies of toffs in ascots or powdered wigs, nor had they heard of the name of Fersht. Never mind all that. The foreigners were lying, Fersht said, to evade taxes. Meanwhile, Governor Nazdratenko’s foes charged that the so-called prize was a money-laundering scheme or a means of buying the votes of the poor as the election approached. “This scheme will try to use the international humanitarian aid for his political purposes,” said a spokesman for Kondratov, the local FSB chief. “I cannot exclude that this money came from the regional budget.”

Nazdratenko’s press secretary Natalya Vstovskaya denied this. “That’s a load of crap,” she said. “Are we not supposed to give humanitarian aid at this point?”

One morning early in 1999, Fersht and the White House called a meeting at the Chamber Drama Theater, where Nonna and I once had once watched an excruciating Russian-American production of Waiting for Godot in which the actors kept forgetting their lines. In Fersht’s spectacle, though, it was the extras who veered off-script. Instead of showing gratitude for the foodstuffs they were promised, hundreds of sour-faced seniors and hard-luck types in threadbare coats and rabbit-skin hats planted their bony bottoms in the seats and folded their arms with a scowl, expecting the worst. And who wouldn’t be skeptical? The meeting was held just a year after a pyramid scheme co-founded by Galina Nazdratenko collapsed, taking with it hundreds of thousands of dollars invested by the suckers who had trusted her. The governor had personally gone on TV to promote the scheme, called the Primorye Food Charitable Fund, but with its collapse, 50,000 people lost their life’s savings. The president of the scheme vanished for a few weeks, only to reemerge a few miles out of Vladivostok in a group of Russian Orthodox pilgrims who were walking six thousand miles to Moscow, carrying crosses and icons. The former pyramid scheme president felt guilty about the whole mess, he did. So he was repenting of his sins. Nazdratenko did not join the pilgrims, but surely he, too, felt bad about stripping his citizens of their life’s savings. Maybe that’s why he was so generous with his million dollars from the baron in Bermuda shorts.

At the Chamber Theater that morning, there weren’t enough applications to go around, and the scowling seniors seemed masochistically gratified to find their worst fears proven right. When Fersht gave a speech thanking Nazdratenko for his generosity, an angry grumbling and a few derisive whistles sounded from the crowd.

A lawyer took the lectern to explain that—hush, people, listen up—the assembled body would need to vote, yea or nay, on whether to create a Council of Independent Organizations and Citizens Living Below the Poverty Level, which would distribute the million bucks as food aid. The council would also have political objectives that everyone present would surely gratefully embrace. See, their benefactor, Yevgeny Nazdratenko, was up for reelection, and so were pals of his at the federal level. This new council could help.

“The chief goal shall be the protection of members’ interests in the election for governor, Federal Duma, and president of the Russian Federation in 1999-2000,” the lawyer said.

The old folks jeered and shouted.

“Who stole the applications?” cried an old woman in a matted fur turban.

Elderly men and grandmas on crutches trundled down the aisle and hobbled up on stage demanding their foodstuffs. No vote could be taken in the unruly crowd.

Fersht’s voice could be heard frantically assuring the crowd that more applications would be printed, and people could apply for assistance at Red Cross the next day. Then he, the lawyer, and the other organizers fled the meeting, leaving a room full of angry pensioners who were convinced the governor had pulled another fast one and stashed his million-dollar prize in a Cypriot bank account. The next day the papers announced that the assembly had gratefully voted to create this Council of Independent Organizations and Citizens Living Below the Poverty Level, which would distribute the aid.

§

I wanted to talk to the goodhearted Baron De Caen, but when I was unable to find him, we pressed the White House for an explanation. Why didn’t a philanthropic organization with what must have been an endowment in the hundreds of millions of dollars even have a rental office with a telephone and a part-time public affairs officer willing to pass along a message to the noblemen running the show? Nazdratenko’s office kept telling me, talk to Fersht, he’s the liaison. Eventually, Nonna and I caught up with him in an upper-floor hallway of the White House. I asked for documentation of the award.

I don’t have it with me, he said. The academy called with the news.

They just phoned? You didn’t get a letter or anything?

They said they’ll be sending it.

Who called you? Do you have a name?

Baron de Caen. He’s very famous.

Do you have a contact number?

I’m afraid not. He talked to my wife.

Wait. So, you’re saying a baron you met in the Caribbean called out of the blue—

—and told not you but your wife—?

—that Yevgeny Ivanovich won a million-dollar prize from a secret society of plutocrats?

Well, yes.

And the governor chose to announce this to the media without any verification?

You know, I’m really very busy. My wife has all the information.

What’s her name, her phone number?

I’m sorry, I have to go.

He slipped into an office and closed the door behind him. Taking with him my dreams of a poolside exclusive in Nassau with Yevgeny Nazdratenko, Rudy Giuliani, Harrison Ford, Demi Moore, the Spanish king, and the child heirs to the British throne.

§

“We Heartily Welcome the President

Of Our Brother Republic, Belarus”

Only once, that I know of, did Yevgeny Nazdratenko share the stage with a worthy peer. In February 1998, more than a year before the Vostoktransflot affair, President Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus stopped over in Primorye on his way home from the Winter Olympics in Japan. Sporting a comb-over and an Augusto Pinochet mustache, Lukashenko clearly regarded Nazdratenko as a kindred soul. Like the Primorye governor, the Belarusian had married his high school sweetheart; she, too, was named Galina. But the Lukashenkos’ union appears to have been less blissful than that of the Nazdratenkos. In a 2005 interview with the newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda v Belarusi, Galina Lukashenko reported that she and her husband had long resided separately, though they remained legally married. Shortly after Lukashenko’s visit to Vladivostok, a series of opposition leaders and journalists in Minsk began disappearing or turning up dead, among them the deputy chairman of the legislature, who was kidnapped and never seen again. An investigative journalist was knifed to death in her apartment, a crime that remained unsolved.

Later Lukashenko reportedly fathered an illegitimate son, a precocious lad, by all accounts. “The child first appeared in public around four years ago, and now sits in on almost all state occasions,” The Independent reported June 29, 2012, when the boy was seven. In a story titled, “Who’s that boy in the grey suit? It’s Kolya Lukashenko—the next dictator of Belarus,” the paper reported that the lad strutted around at major military events brandishing a golden pistol. Generals of the army were obliged to salute the child, who was also a fixture on his father’s infrequent foreign trips. Kolya even met Pope Benedict XVI. But all this happened long after I heard Lukashenko speak.

The day I saw him, Lukashenko joined Nazdratenko on stage to address a hall full of apparatchiks and black-uniformed naval cadets at the Marine Academy. The curtains and bunting were commie red, and onstage a giant bust of Lenin wrathfully jutted his muzzle like a Scottish terrier that has spotted a squirrel on the other side of a window pane and can’t get at it. Strung across the front of the auditorium was a banner that read, “We Heartily Welcome the President of Our Brother Republic, Belarus,” as if Primorye, too, were an independent nation. Lukashenko likes to refer to the representative form of government as dermocratia— a pun that translates as “shitocracy.” The crowd laughed when Lukashenko recalled breaking up a protest by “fascists” who opposed his government, and they clapped when he warned that other nations are scheming to conquer Russia. Applause also broke out when Lukashenko fantasized about dealing with economists who wanted Belarus to adopt a Western-style market economy: “I wish they could go to the ore mines and work there and see what the real economy is like.” The Belarusian won a standing ovation in the end. Then Nazdratenko took the dais to sneer at members of the Yeltsin government with “Jewish names.” It was a hand-picked audience, but still: I could not find anyone who was troubled by the event.

I relate all this for a reason. Lukashenko flew on to his presidential palace in Minsk, where his first lady surely was not waiting to welcome him with bread and salt, being previously engaged in a small village she had never quite managed to leave. And the rest of us found the wherewithal to carry on with our lives in the anticlimax that follows any great historic moment. But the next day a senior editor of our parent paper dropped by with a tip. At a banquet honoring the Belarusian statesman, Nazdratenko had given his guest the skin of a Siberian tiger, head attached, mouth open and snarling. Fewer than five hundred of these great cats survive in Russia, and it is illegal under international law to hunt them, traffic in their parts, or transport them abroad. The Vladivostok mentioned the tiger skin deep in a fawning story: “The Governor of Primorye gave Alexander Lukashenko a tiger skin as a gift and advised him to look at the fangs in the mouth of the lord of the taiga in order to remember the most radical way to answer the attacks of his foes in Minsk and Moscow.” The reporter claimed that Nazdratenko possessed documents that somehow made the gift legal.

But that morning we heard a different story.

“There were no documents,” the editor told us. “It was completely illegal.”

“Why aren’t you guys writing this?” Nonna said.

“We can’t,” the editor said. The publisher would not allow it.

Nazdratenko visits a museum. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

Nazdratenko visits a museum. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

So alone among Vladivostok’s media, the Vladivostok News reported the story as a potential violation of international law. Primorye’ environmental prosecutor, who routinely sought jail terms for tiger poachers, refused to pursue the matter. “I have no authority to interrogate the governor,” he said.

After I wrote about Lukashenko’s tiger skin for our little paper and The Moscow Times, The Los Angeles Times followed up with a story that asked, “So what do you give the authoritarian who has everything? Well, if you’re a provincial governor in Russia’s Far East, you give him the pelt of an endangered Siberian tiger.” Having stirred up this row, we awaited an angry call from the White House, but it never came. Our paper was even on sale in a gift shop in the White House lobby. It was the first of many stories that taught me that the White House and its alleged allies in the mob did not know or simply could not care less what we published in English.

As Lukashenko left Russia, a keen-eyed customs officer discovered the tiger skin in the presidential luggage, according to news reports. After a moment of embarrassment and consultation with his superiors, he waved the visiting head of state on, and Lukashenko brought his trophy home to Minsk. No doubt to this day it lies beside a fireplace in some palatial hall, where from time to time a senior adviser drags his father to the floor for a tickling match while the Joint Chiefs of Staff applaud.

§

Her Majesty’s Scheme

To Scuttle the Fleet

With the Help of

Imperialist Sharks and Vultures

By 1999, one of the few foreigners who was still bullish on Vladivostok was a British businessman named Andrew Fox, a wry, bearded man in his mid-thirties who somehow reminded one of his namesake. The son of a Reuters reporter and grandson of a Russian émigré, Fox was a Cambridge University graduate who owned a brokerage called Tiger Securities. In a region where mobster-tycoons traveled with platoons of body guards, Fox had no security. He avoided the ostentatious displays of wealth that made the word businessman synonymous with mafioso in Russia—the gem-encrusted rings and convoys of SUVs and drunken bacchanalias at night clubs and duffle bags full of U.S. dollars. Fox was married to a Russian and spoke the language, and he lived in a three-room flat, with a small dacha on nearby Russky Island. Impressed with his thinking on business in the Russian Far East, the British government named him its honorary consul. But like Milashevich, he drew Nazdratenko’s attention because of his interest in Vladivostok’s commercial fleet. His offense: investing on behalf of Tiger’s foreign clients in Far Eastern Shipping Co., or FESCO, which was the world’s largest shipping line. Foreigners held 42 percent of the company’s shares. (Milashevich also was a director and key shareholder at FESCO.)

In June, just as the Vostoktransflot affair was brewing, Nazdratenko began attacking Fox in speeches, press conferences, and the media. The governor denounced the Britain as “an imperialist shark” and “a vulture who’s robbing Russia.” The tabloid Novosti—the same one that published the trade union leader’s letter accusing me of thinking Russians wore velveteen trousers—stated that Fox wanted to sell off FESCO’s entire fleet, so that “we will have to close all the maritime academies of Russia and delete Russia from the list of seafaring countries.” Apparently unaware of Fox’s status as an honorary diplomat, Nazdratenko announced in a press conference that he was ordering the main successor agency to the KGB to investigate whether Fox had illegally obtained the shares held by his clients. On June 3, Nazdratenko summoned Fox to the White House. In an office overlooking Zolotoi Rog harbor, Fox found himself seated at a table with perhaps thirteen or fourteen people: Nazdratenko, several vice governors, and uniformed FSB officers with medals on their chests (by now Kondratov had been recalled to Moscow). The governor told Fox he was going to throw him in jail if he did not somehow convince foreigners to meet three demands: appoint a FESCO chairman of Nazdratenko’s choosing, elect a board friendly to the regional administration’s interests, and sell the regional administration a seven percent stake in the company. Since Fox himself could not order other foreigners to sell their stock, it is unknown how the governor expected him to hand over the shares, but a basic appreciation of the workings of business never was Nazdratenko’s strong point.

Rusty ships in Zolotoi Rog harbor. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

Rusty ships in Zolotoi Rog harbor. Photo by Yuri Maltsev.

This spring while participating in a writing fellowship in Brussels, I visited Fox in London. He grilled a slaughterhouse’s worth of chicken, beef, and ribs, and we sat out under a blossoming magnolia tree in his back garden with his two daughters and the Dutch boyfriend of one of the girls. His eleven-year-old son and three of his friends marauded through, loading their plates, then vanished upstairs to play video games. As the daughters and boyfriend listened, wide-eyed, Fox and I swapped stories about Russia’s “Wild East” until a hailstorm drove us indoors. As a joke, Fox also presented me with an artifact of White House propaganda: a chapbook called The Favorite Songs of Yevgeny Nazdratenko, printed up by the regional administration.

In his meeting with Nazdratenko and the sub-bosses of Primorye, Fox recalled, the governor explained the consequences if the foreigners did not comply: “He told me he would put me in a small room in Partizansky Prospekt”—the local jail.

Fox flew to Moscow and held a press conference to reveal the threat, and it became an international scandal for Russia, with Her Majesty’s government denouncing the bullying. Media ranging from the BBC to The New York Times covered the case. Nazdratenko’s intimidation not only undermined diplomatic norms but threatened private investment in Russia. Nazdratenko’s staff hastily denied he had threatened anyone and only said he had spoken to Fox in a “manly” fashion.

But that did not put a stop to the pressure. The drumbeat against FESCO continued when Nazdratenko’s allies in Vostoktransflot’s leadership hired buses to bring maritime academy students, sailors, sea captains, and others to downtown Vladivostok for a protest. A thousand people showed up to denounce Russian businessmen close to Fox as “agents of imperialism.” From the dais, Vladivostok Mayor Yuri Kopylov excoriated a local journalist whom he noticed at the edge of the crowd interviewing a business partner of Fox’s. “She won’t be a reporter for long,” he told the crowd.

Nazdratenko pressured the FESCO board to appoint his candidate to head the company. His man for the job was Aleksandr Lugovets, who happened to be Russia’s Deputy Transportation Minister. Fox replied that Lugovets was unacceptable to foreign investors, who were insisting on a Western level of accounting and transparency. There seemed to be little chance Lugovets would land the job, because board members allied with the foreigners were in the majority. But at a July 6 board meeting, an American board member and a former employee of Fox’s named Richard Thomas threw in with Nazdratenko against the foreign shareholders, handing Lugovets a six-to-five victory. I do not know why Thomas voted as he did, because he did not respond to my inquiries at the time. (He had been editor of the Vladivostok News before my time.) The foreigners Fox represented ended up selling their shares to the Primorye regional administration.

§

By September of 1999, Vostoktransflot’s debts under Ostapenko exceeded the assets of the company, according to media reports. Thirty-four of its thirty-eight ships were arrested to be sold for debts, with one of them to be auctioned off in Lagos, Nigeria. The four remaining ships were docked in Vladivostok, where they had returned in July at Ostapenko’s orders. None of the crews had been paid under his management. Wage arrears to Vostoktransflot’s employees ran in the millions.

The turmoil in the company briefly drew the attention of the federal prosecutor general, Vladimir Ustinov, who flew to Primorye to sniff around. But Russia had changed since the days of Gogol. No one trembled as Gogol’s governor did before the man he mistook for the inspector general from Moscow (“My God, how angry he is. He has found out everything”). Ustinov’s assistant spoke with Vostoktransflot’s legal adviser, Taisia Ponomaryova, who claimed to have evidence of corruption in the Primorye prosecutor’s office and said she possessed documentation proving that a Mafia gang known as the Larionov brothers had gained control of Vostoktransflot through front organizations and that Ostapenko was linked to the brothers, the newspaper Kommersant reported. Valery Vasilenko, the Primorye prosecutor general, dismissed her accusations as nonsense. Anyway, nothing came of Moscow’s interest. Ponomaryova was scheduled to join Milashevich in Moscow for a meeting with Ustinov.

Her phone began ringing at night. Callers she did not know wished to offer a word to the wise. She’d end up beneath the ground with her feet to the east if she kept stirring up trouble, capisce? And it turned out these dial-up friends possessed an uncanny clairvoyance, or must have access to tarot cards or soothsayers, for how else could they have foreseen what would happen at her suburban dacha on the night of September 12, 1999, when she went to bed, and either did or did not say her prayers or think the warm thoughts of the night or reassure herself that a Moscow prosecutor was now paying attention and nothing could happen to her? After she turned out the light, she was blown to bits by a half kilo of TNT.

Suspects? Ostapenko, the new director of Vostoktransflot, wanted to make clear he was not to blame for the “accident.” (The word choice was important, because, who knows, maybe Ponomaryova had in fact bought a child’s chemistry set and stashed it under the bed in an unsafe manner. It does happen.) He issued a statement denying any involvement by his office: “Some media have run absolutely false information on the alleged complicity of the present lawful administration of [Vostoktransflot] in the tragic death of Taisia Ponomaryova. In this connection, the acting administration has to state that it does not have anything to do with the accident.” Besides, he had been sick at home the week of the bombing. How could he be involved?

Well, all right, then; scratch Ostapenko off the list of suspects. What did Alexander Shcherbakov, prosecutor of the Pervomaisky district of Vladivostok, think about all this? He quickly denied any wrongdoing in raiding Vostoktransflot and kicking out Milashevich’s team. He said his office investigated all the facts and concluded that the court executors and the police were acting in full accordance with the law.

Nazdratenko? He was never implicated or named as a suspect. Who said he was? But the governor now controlled Vostoktransflot through the new board of directors, the media reported.

One of Russia’s greatest shipping companies was now falling to pieces. Foreign investors were panicking. Six ships under the Cyprus flag, pledged to the Bank of Scotland, were arrested by Nazdratenko in the port of St. Petersburg in what he said was “the national interest,” Milashevich recently recalled. And anyone who questioned the current ownership arrangement was encouraged to see things the governor’s way. Chief Judge Tatyana Loktionova, head of the Vladivostok department of the State Arbitration Court, was overseeing a case concerning Vostoktransflot’s bankruptcy, and she said she was sure Ponomaryova had been killed because of her attempts to establish corruption in the Primorye administration’s handling of the Vostoktransflot affair. This was not the first time Loktionova had heard a case that interested the White House. Once Nazdratenko phoned her and demanded that she place a crony of his as external manager of a shipping company called Yuzhmorflot, she told Nonna in an interview. And Loktionova, too, had been receiving phone calls from strangers urging her to get with the program and start ruling in accordance with the White House’s wishes, or else. Just before Ponomaryova’s assassination, Loktionova allowed Ponomaryova to copy some files to give to the federal prosecutor general, the judge said. That same day, her neighbor stumbled upon a stranger leaving a package outside Loktionova’s apartment door. Caught in the act, the man grabbed the gift and ran off. She believed it was a bomb.

“This time I again wrote to the local police and the FSB and asked for bodyguards, but I haven’t been given any,” she said. “I am afraid for my life and the life of my husband.”

She sent her two daughters, eleven- and twenty-four years old, into hiding.

“Loktionovs to Kolyma”—protesters outside the courthouse call for Chief Judge Tatyana Loktionova to be sent to one the most notorious Stalin-era gulag camps. Photo by Vyacheslav Voyakin.

“Loktionovs to Kolyma”—protesters outside the courthouse call for Chief Judge Tatyana Loktionova to be sent to one the most notorious Stalin-era gulag camps. Photo by Vyacheslav Voyakin.

§

Meanwhile, Vostoktransflot’s sailors and workers were going unpaid once again. After Ponomaryova’s death, the White House-allied local media began falsely reporting that Loktionova had frozen the company’s bank accounts. This was untrue, but it had the desired effect. On September 22, a hundred-odd protesters, identifying themselves as sailors, began camping outside Loktionova’s court in a round-the-clock demonstration. Russian police are not known for their tolerance of protests, but this crowd was allowed to remain there for weeks, shouting at anyone they recognized who entered or left the courthouse. Some of them carried signs that read, “Nazdratenko, you were a thousand times right.” Another sign, decorated with a set of handcuffs, said, “Send the Loktionovs to Kolyma,” a reference to a far northeastern region notorious for its Stalin-era Gulag camps. The protesters slopped graffiti on the walls denouncing Loktionova, and they brought in lifeboats, gray with orange covering, which were absurdly beached on the sidewalk along Ulitsa Svetlanskaya. Court employees complained that the seafarers were swigging from bottles and were often, quite frankly, drunk. The sailors chanted their support for the new boss, Ostapenko. This was remarkable, given that all the Vostoktransflot employees I had ever talked to were angry at their chief executive for failing to pay their wages.

On October 4 the protest grew violent. The former acting general director of Vostoktransflot showed up to the courthouse. The protesters dragged him from his car and beat him up. It took another three days before the Primorye regional prosecutor’s office finally ordered the crowd to clear off. As Loktionova left the courthouse that afternoon, police officers escorted her out. As she tried to drive off, roughly a hundred protesters surrounded and began rocking her minivan, shouting, pounding on it, and trying to tip it over.

“We’ll stay here until we kill you,” they screamed.

Demonstrators protest against Loktionova in the Vostoktransflot case. Photo by Vyacheslav Voyakin.

Demonstrators protest against Loktionova in the Vostoktransflot case. Photo by Vyacheslav Voyakin.

For a half an hour the crowd would not let the judge leave, witnesses said. Eventually, police reinforcements arrived and freed the van. Loktionova escaped unharmed. In a later interview, she told us she had become a scapegoat for the governor’s office because of the bad regional economy. She believed Nazdratenko had drummed up the protest as a part of his re-election campaign. “Just look at the posters praising him,” she said.

The governor’s office dismissed this. “It’s an absurd statement,” said spokesman Andrei Chernov. “It doesn’t have any grounds. The governor does support Ostapenko’s management just because the previous managers couldn’t provide salaries to the sailors.”

Ostapenko held on as company boss, and a year later, Loktionova again found herself under fire. Prosecutors accused her husband of accepting bribes from two businessmen who were trying to influence his wife’s rulings. She herself was never accused of wrongdoing, and she said the charges were trumped up, but the stress took its toll. She was diagnosed with high blood pressure, a nervous condition, and a heart ailment, and doctors admitted her to the hospital. But days later, the chief physician of Primorye, Polina Ukholenko, personally showed up in Loktionova’s room and kicked the judge out. Loktionova sought admission to other hospitals, but they all refused. “They politely told me to go home, as they didn’t want to get in trouble,” Loktionova said. No other clinic or hospital in the region would admit her.

Ukholenko denied that Loktionova was being refused medical treatment, and claimed that the judge was perfectly healthy. “We did not order clinics not to take her,” she said. “The doctors who denied her help bear full responsibility for her health.”

The New York-based Lawyers Committee for Human Rights wrote to President Putin to complain that Nazdratenko was intimidating judges through smear campaigns in the media, threats by police and government officials, fabricated criminal charges, and physical violence. “This strong-arm governor appears to operate without any external controls, giving him free rein to threaten anyone who challenges his status quo,” wrote Robert Varenik, director of the Lawyers Committee’s Protection Program.

But the letter had no effect. The Higher Qualification Collegium of Judges, a professional licensing body, voted to dismiss Loktionova and strip her of her status as a judge in response to the criminal charges against her husband. He had not yet been convicted, nor had she been accused of anything. Never mind. Nazdratenko had won again.

§

The Goat in the Garden

Let us return to the tale of Radio Lemma. In July of 1999, shortly after the beating of Stepanov and threat to the editor through his kidnapped daughter, the building management company cut off electricity and ordered the staff to clear out of its city-owned office and studio. The reporters who arrived to cover this mostly worked for the national media, beyond Nazdratenko’s control, and Nonna and I also showed up. There in the dark, station director Alexander Karpenko told us that Radio Lemma had asked the city property committee to halt the eviction order, but the request was ignored.

“We have appealed to the governor and to Mayor Kopylov,” he told us there in the dark. “I can’t call this situation an accident after all this noise and all this scandal.”

I do not know how Radio Lemma got the power restored, but somehow the station found its way back onto the air. Then late in November, the month before the regional elections, with Nazdratenko on the ballot, the phone rang at the Vladivostok News. It was Marina Loboda, a local reporter for the national newspaper Moskovsky Komsomolets.

“The mayor’s shutting down Radio Lemma,” she said. “Get over here.”

We flagged down a car whose gold-toothed driver intuited our urgency. On the road over a mountaintop that pokes up in the city between our offices and the downtown, he kept his foot to the gas, demonstrating Formula One moves on bald tires as he screeched around the curves. Nonna asked him to slow down. He grinned and ignored her. We clung to the armrests. The Japanese cars widely used in the Russian Far East have no seatbelts in back, and for that matter, drivers themselves seldom buckle their shoulder straps, regarding this as unmanly. From the mountaintop we saw Zolotoi Rog harbor laid out before us, the slump-shouldered cranes, the rust-streaked ships at dock, the barren November hills; and we found ourselves contemplating the shortness of this blessed life. But our time had not yet come, and we screeched up safely outside the offices of Radio Lemma. It was swarming with armed cops.

As a foreigner thought to be The New York Times’ guy, I could breeze in and cover a story like this without risk. For the Russian journalists, it took guts just to gather outside the building in the November wind, clutching a notebook. Loboda, the Moskovsky Komsomolets reporter, once said that whenever she filed a story on a dangerous topic, she holed up in her apartment, fearing that something bad was going to happen to her. She and a few others from the national media were there, but this event would not be well-covered by Primorye’s media. Possibly Arsenyevskiye Vesti was there; they had been showing guts in covering the shipping scandals.

The cops wouldn’t let reporters inside. I buttonholed a young lieutenant, who told me the radio station had been storing gasoline to run its generator. This was a fire hazard, he said. The authorities were compelled to act in the interests of public safety. That was all.

I told him, “I don’t believe you.”

Anger flashed in his eyes.

He referred further questions to his captain, who shrugged that orders were orders. I asked, “Why are you doing this when the Russian constitution guarantees freedom of speech?”

A look of alarm and confusion momentarily crossed his face, as if he had received no instructions as to this point. But the raid went on, and Radio Lemma was off the air until after the election in December. It touched and saddened me later that week when Andrei Kalachinsky, one of the courageous reporters who were there, told Nonna he admired the aggressiveness of my questioning. This compliment was undeserved, particularly from Kalachinsky, who was fired from several jobs because his investigative reporting angered the governor. Later, a pliant court would attempt to seize Kalachinsky’s car after Nazdratenko sued the journalist for an article in the Moscow newspaper Novye Izvestia. (Nazdratenko eventually dropped the case. Uncharacteristically, he shook Kalachinsky’s hand the next time he saw him.) The heroes were the ones who filed their stories and then hid in their apartments, worrying about bombs under the bed. And also my wife, who never hesitated to ask the toughest questions.

Nazdratenko’s campaign in December was filled with attacks on “greedy foreigners” and their Russian allies, and he portrayed himself as a patriot fighting to preserve the Russian fleet. Yet in Vladivostok he was almost beaten by his political rival, Alexander Kirilichev, director of Primorsk Shipping Company. A majority of those we spoke to at the polling stations on election day said they were voting for Kirilichev. Milashevich also ran, but when I asked him what percentage he won, he said he did not remember—maybe 5 percent. “But it does not matter, because the practice of election fraud had already begun,” he wrote. “For example, I cannot believe that Nazdratenko, who froze Vladivostok and left it in the winter with no electric light, scored as much as 75 percent.” As for Kirilichev, he claimed he could prove the election was stolen, but the courts owned by Nazdratenko and the regional election commission found his evidence insufficient.

§

All good things must pass, and while Russian tsars and presidents will forever serve for as long as the state requires them—i.e., for life—mere governors rise and fall. (“No man in this country is irreplaceable—except for one,” Russians used to say under another ruler-for-life, Stalin.) Nazdratenko lost his job, and when he did it happened abruptly.

By the winter of 2000-2001, the Kremlin was embarrassed by the electrical and heating crisis four thousand miles away along the frozen Sea of Japan, and by the foreigners who persisted in writing about it, not just me but the foreign press corps in Moscow as well. Every year Moscow dispatched millions of rubles to buy coal for Primorye’s power stations and boiler houses, and yet in city after city the budget evaporated and ice formed on the interior walls of apartment blocks. In our apartment, Nonna and her son Sergei and I slept in sweats and long underwear and gloves under heaps of blankets, and in the morning, when I got up at four to write fiction, I wore my fur hat and sheepskin coat and fingerless gloves. During the day, amid sixteen-hour blackouts, I scrounged electricity in places where it stayed on. By now I was freelancing and no longer went in to the Vladivostok News to work, so I had to plug in my laptop in the restaurants of international hotels, which had generators to keep the power on. For eight hours at a time I sat there ordering coffee after coffee, so the staff would not kick me out. Or I tipped the waitresses and asked them to leave me alone.

Others could not afford such luxuries. Citizens staged hapless protests—blocking traffic for less than an hour on the main road into Vladivostok one night when the city was so dark, you could see the Milky Way spilled against the void of space. But the regional administration told us we were wrong to complain. First Vice Governor Tolstoshein said there was no energy crisis in Primorye. They were fools and liars, those citizens who complained about living in an apartment where ice formed in their toilets.

President Vladimir Putin was still new on the job, just a year after Yeltsin’s New Year’s Eve resignation had placed the former KGB man in power, and, funny to think, the leader who may now be the richest man on earth was then subject to hopes that he might be a reforming tsar, willing to crack heads together and set things right. Citizens of Vladivostok were cheered in late January when he assailed Nazdratenko for the heating crisis and called the situation in Primorye “utterly outrageous.” Boris Reznik, a State Duma deputy from neighboring Khabarovsk region, told The Moscow Times that Primorye was a “bandit’s nest … one of the most corrupt regions in the country. The fuel crisis was just a consequence.” Russia excels at allowing problems to reach a crisis point, and then heroically solving them. Putin shoveled emergency funds from the federal treasury to be incinerated in the boiler house of Primorye, and he sent his own inspector general in the person of Emergencies Minister Sergei Shoigu to investigate what might be amiss in Primorye—that is, apart from rampant criminality, theft at every level, and a governor who claimed he had been honored by an international brotherhood of blue bloods. Federal prosecutors began pressing criminal charges in connection with Primorye’s energy problems, and a mayor was found guilty of gross negligence. Cargo planes full of radiators and pipes thumped down on Vladivostok’s concrete-slab runway, and other regions sent plumbers and welders to help restore heating, Reuters reported in January. Moscow ordered other regions to ship coal to Vladivostok, but their governors balked, saying they would run out of fuel if they had to pour their supply into the rat hole by the Sea of Japan. Primorye’s scandals were beginning to touch them. They were angry. The upper house of the federal Duma, in which governors serve, scheduled a debate on the heating situation in the Far East and Siberia. There was the sense that this would not end well for Nazdratenko.

All this drove the sensitive blueblood the point of physical collapse. Taking Loktionova’s lead, Nazdratenko reported to a clinic, claiming serious heart trouble. Luckily, the doctors didn’t kick him out. Reuters cited a regional spokesman who said that “Nazdratenko, the target of a blistering attack by Moscow for alleged blatant mismanagement of the region’s infrastructure, had ended up in hospital after suffering a family loss and because he took his people’s plight to heart.”