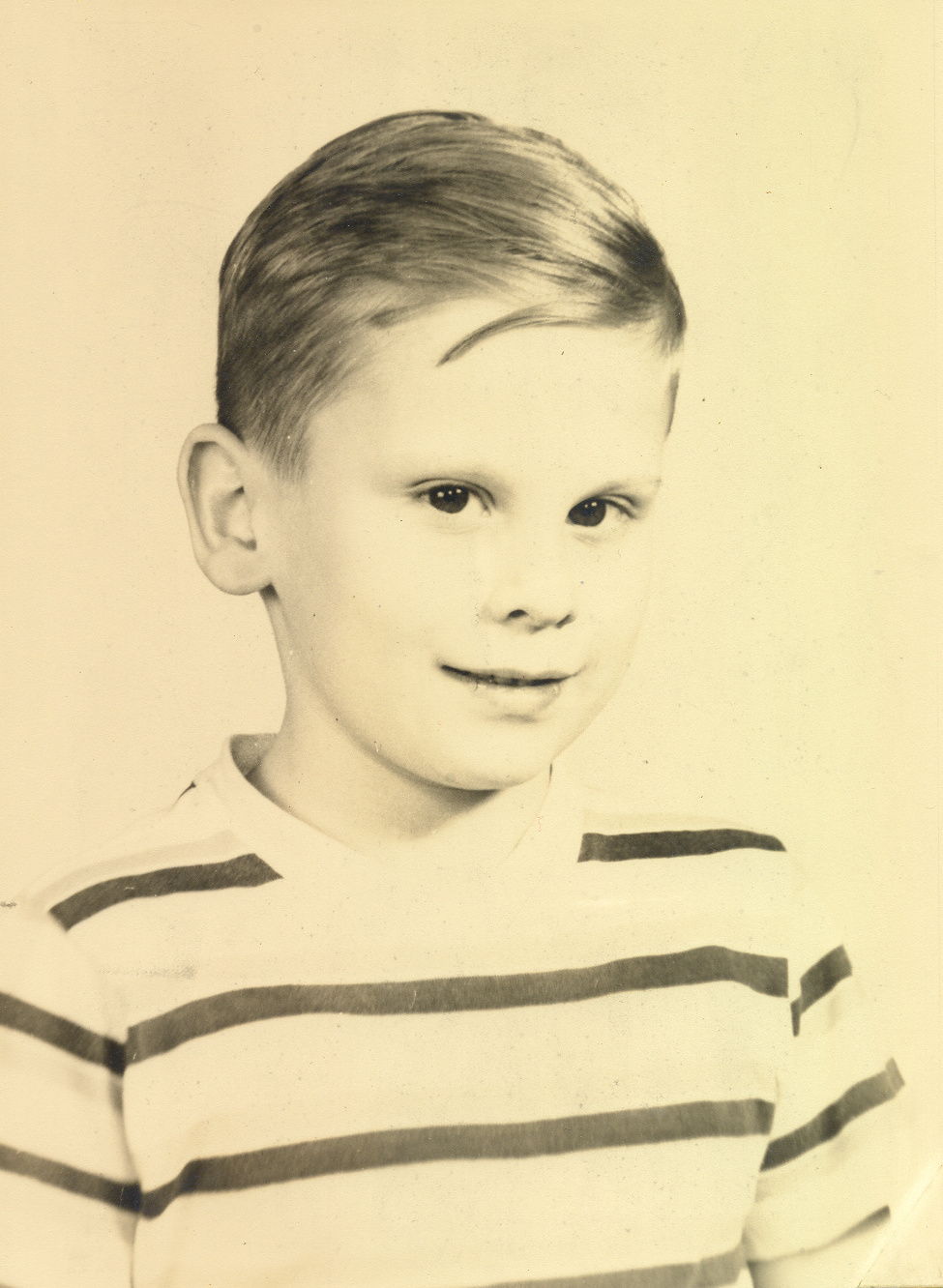

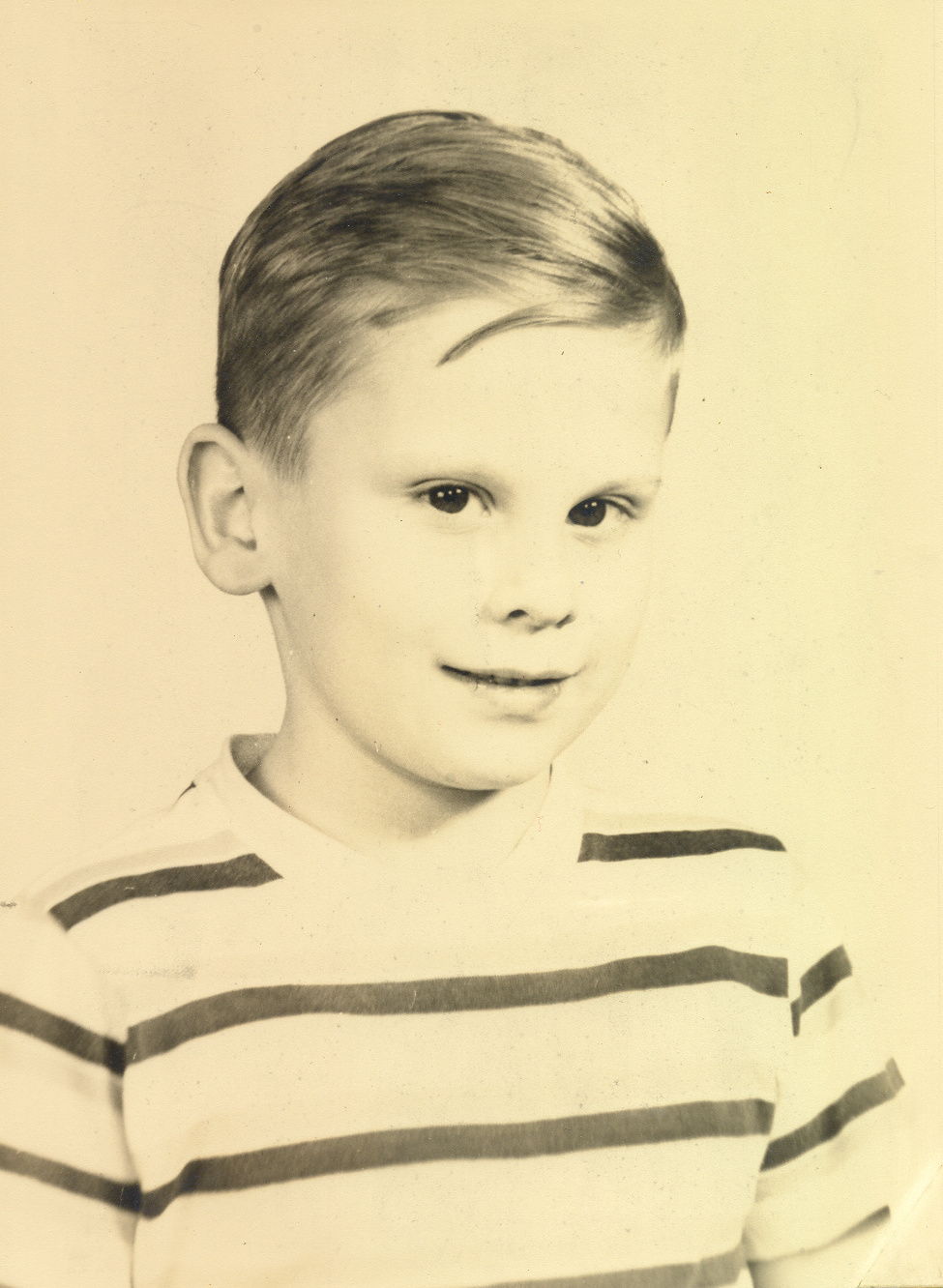

Because he had a difficult time pronouncing “Keith” when he was a child, Keith Maillard called himself “Keats.” Because he was sick a lot, he made up stories; he drew stories on the bathroom tiles and his grandmother cleaned them off every day so he could do more the next. Because he was a kid during the Second World War, he thought Kilroy was a magical, ubiquitous person. Herewith is a second excerpt from Keith Maillard’s memoir Fatherless (NC published “Richland” in March). It goes straight to the heart of childhood, that gorgeous, magical moment in time when adults are mythic creatures, the night holds unspeakable terrors, words are mysterious and difficult to control, illness visits and strange medicines applied, and the self applies itself fiercely and joyously to the task of understanding. Keith Maillard was born and raised in West Virginia. Currently the Chair of the Creative Writing Program at the University of British Columbia, he is the author of thirteen extraordinary novels and one poetry collection.

dg

.

I’ve always had the impulse to tell stories. It must have started with wanting to hear stories. When I was little, my mother put me to bed by telling me the adventures of Bucky the Bug, a tale that she made up on the spot, that evolved day to day. I was so little that I had to go to bed before it was dark. “You never minded,” my mother told me. “You always wanted to hear the next part of the story.” Those summer nights, as they settled down on me, felt as huge as continents. The light would be fading out at the windows; I’d be tucked into bed but not sleepy yet, and my mother would be telling me what was happening to Bucky the Bug right now. I don’t remember the stories, but I do remember the sense of living inside them. When my mother stopped telling me stories, I begin to tell them to myself. As soon as I could, I notated them—first with stick figures, then, much later, with words.

The lower half of our bathroom walls was tiled. Each tile—cream-colored and blank—looked to me like the panel of a comic strip. I’d sit on the bathroom floor and draw on the tiles with a soft lead pencil, filling in each one with the drawing that went with the story I was telling myself, working my way around the bathroom walls until I had filled all of the tiles as high as I could reach. Every evening my grandmother would scrub them clean with Ajax Cleanser so I could start over the next day and do it again. I felt no sense of loss when my comic strips were wiped away. I loved waking up in the morning knowing that I had all those shining blank tiles to fill—more than I could count—unending rows of cartoon squares where I could tell myself stories.

When I got older, I moved from bathroom tiles to paper. I was sick so much as a child that they bought me a bed table and a special wedge-shaped pillow so I could sit up and draw. Whenever I got sick, I had to take unbelievably nasty blue pills called “pyrobenzamine.” My grandmother would smear my chest with Vicks Vaporub, cover it with a layer of cotton, then a layer of cloth—thin t-shirt material. She’d set the vaporizer going in the corner of my bedroom; it hissed quietly, making everything steamy and scented of camphor. She turned on the radio for me—a box made of Bakelite with a green dial. Voices from the radio told me stories as I drew my own stories. The first two fingers of my right hand became callused from holding pencils and crayons. Sometimes I had fever dreams as thick with images as wallpaper. In my earliest years I had visitations that were worse than nightmares.

Night terrors occur in the early part of the sleep cycle when there’s no rapid eye movement. They afflict toddlers and young children, can be deeply frightening to adults if they don’t know what’s happening—as my mother and grandmother didn’t. Adults often describe the children as looking possessed. They cry out. They’re obviously deeply distressed, and sometimes stare fixedly at something just beyond their field of vision. Most children, when they have night terrors, don’t remember them, but I remembered mine. My mother and grandmother kept saying, “Look at his eyes, look at his eyes, look at his eyes.” I don’t know what my version of “Oh, my God!” would have been, but that’s what I was feeling. My mother and grandmother’s voices sounded rumbly, echoey, as though they were in another room, a huge one with stone walls. I couldn’t move a muscle—Wrong with my eyes, wrong with my eyes, what could be wrong with my eyes?—heard them saying over and over again, “Look at his eyes.” My eyes, my eyes?

Another time it was a shower of pins that were many different colors. They weren’t nice colors, like rainbow colors; they were sharp nasty colors—blue and black and red—and they were falling in a thick cloud of little pins all lined up together, not dispersed, coming down all together. From the way I was seeing them, they were above me and to the left—a countless number, millions of tiny pins raining down on me, trying to do something pitiless to me. I don’t know how long I had night terrors, but they made the night dangerous. I tried to keep them out by pushing on the front door to hold it shut. I might have sleepwalked there; I was not fully awake—I know that—and the radiating glow of that awful yellow light, threatening, disgusting, smeared through the curtain on the door, on our door that led outside to where there were things. I drew that shower of pins. “Like that, like that. It looked like that.”

When I’d first been learning to talk, Keith had been hard to say, so I had become Keats. That’s how I thought of myself, and for years that’s how I signed the cards I gave my mother and grandmother at Christmas and on their birthdays. While I was still inside that eternity of “not-in-school-yet,” I consumed comic books like peanuts, and the classic, iconic pop-culture images from the late Forties flowed into my own stories. Like Batman, I drove a sleek, murderously fast car jammed with amazing modern gadgets; mine was called “the Keatsmobile.” My headquarters was a complex series of interlinking caves deep underground beneath our apartment; the walls were lined with jewels—diamonds and rubies and emeralds and sapphires—and I could see them in my mind, fabulously glittering, as I strode down the corridors. This wondrous place, my home inside myself, was called “the Keats Cave of Splendor.” I lived there with a dozen or so of my friends, and I was the ruler of that world, the fearless hero in charge of the whole works. Like Superman, I wore a uniform with a cape; the letter K was emblazoned on my chest. My best friend and constant companion, my advisor, my right hand man in the Keats Cave of Splendor, was Kilroy.

In the war that was just ending—the terrible exciting war I saw in movies and newsreels and magazine photographs—Kilroy had been everywhere. Wherever our soldiers had gone—even into the most dangerous, bombed-out, desolate, death-ridden cities of Europe—Kilroy had always been there ahead of them. He left drawings of himself, two little dots for eyes, his big nose hanging over a fence, and his eternal message: “Kilroy was here.” The GIs kept trying to find some place, any place at all, where Kilroy had not been there ahead of them, but they’d never been able to find it. That’s the story of Kilroy as my mother had told it to me, and I was lucky to have Kilroy as my best friend. Because he’d always been there first, he understood everything. If I was ever confused or upset, Kilroy would come and explain to me what was going on and why things were happening the way they were. He was a magician, a shaman—my tutelary deity, my guide, my mentor—and these are all adult words. In my childhood he was simply my pal. He was a wise man who knew everything, who could tell me everything I needed to know. He was—and it’s taken me sixty years to see this—someone like a father.

My first work of fiction, written in my head and notated in stick figures that were wiped away every evening, was entitled “Kilroy and Keats.” What we did in the Keats Cave of Splendor was fight against evil. I knew what evil was because I had stared at it when no one else could see it, because it had rained down on me like pins. I knew that evil sometimes sniffed around outside our front door. Evil is what the Japs and the Nazis had done to people—the worst things that anybody could imagine—and they’d done it happily and laughing like the villains in Superman and Batman stories. There were things called “concentration camps” where the Nazis had done really evil things, but Kilroy had been there, and he could explain it to me—how people could have done things like that.

I can remember—just barely—when the War was still going on, imagining it on the other side of the river, but I can’t remember it ending. I told my mother that I wanted to build a fort in our back yard. She said she’d help me do it, but that we’d better put little American flags on it so that when our planes came over, they wouldn’t bomb it. I was terrified. If there was even the faintest possibility that our planes would bomb my fort, then I simply would not build a fort, and I never did. Later—how much later, I don’t know—it came to me in a flash: Nobody would bomb a little fort in our back yard. My mother had lied to me. Kilroy would never lie to me.

We were Americans, and we’d won the war. We’d beat the evil Japs and Nazis. We’d beat them with the bombs that I saw in newsreels, atom bombs brighter than a thousand suns. Kilroy knew all about them. He’d been in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and watched them fall.

—Keith Maillard

![[Now, the storm has arranged the insane]](http://dgvcfaspring10.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/1-again1.jpg)

It’s a pleasure to introduce the first play ever published on Numéro Cinq, God’s Flea by Diane Lefer (wise friend, former colleague at Vermont College of Fine Arts—in the mid-1990s, when I had a radio show, I interviewed her, still have that tape). God’s Flea is an uproarious piece of political folk theater. Set on the Arizona-Mexico border, it borrows from the tradition of

It’s a pleasure to introduce the first play ever published on Numéro Cinq, God’s Flea by Diane Lefer (wise friend, former colleague at Vermont College of Fine Arts—in the mid-1990s, when I had a radio show, I interviewed her, still have that tape). God’s Flea is an uproarious piece of political folk theater. Set on the Arizona-Mexico border, it borrows from the tradition of