.

Three days after the fortuitous capture of Salah Abdeslam, Europe’s most wanted man for four months, the BBC published a profile of his lawyer, Sven Mary. The title of the piece was deliberately incendiary and utterly telling of the sentiment prevalent in Paris, in London, in Brussels, in Europe: “Sven Mary: The Scumbag’s Lawyer.”

Despite his notoriety in Belgium as a high-profile defense attorney, I had never before seen a photograph of Sven Mary – indeed, I hadn’t even heard the name until I clicked on the aforementioned piece. Hence, it’s fair to say that I had never really had much of a chance to build a balanced image of the lawyer in question, my judgment necessarily skewed by the tone of the very first notice I had of the existence of this man. This circumstance immediately made me think of Atticus Finch, the hero in Harper Lee’s novel To Kill a Mockingbird.

Sven Mary

Sven Mary

The connection, I must confess, was neither fortuitous nor particularly inspired. I had already been working on a tribute to Lee, and the parallels are, of course, immediately obvious: set in 1935, in the archetypal small town of Maycomb, Alabama, To Kill a Mockingbird spells out in endearing terms the tense situation that unfolds when Tom Robinson, a black man, is unfairly accused of raping Mayella Ewell, a disenfranchised young white woman. Entitled by law to a defense lawyer, Robinson is paired up with Atticus Finch, the unofficial standard-bearer of integrity and fairness in a town where prejudice is rife – though no more so, I would suspect, than in any real-life small town of the South at the time.

Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch in the film version of To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962.

Gregory Peck as Atticus Finch in the film version of To Kill a Mockingbird, 1962.

Narrated from the perspective of Atticus’ eight-year-old daughter Scout, To Kill a Mockingbird vividly portrays the life-changing consequences faced by the Finch family once Atticus agrees to defend Tom Robinson: Scout and her elder brother Jem are relentlessly bullied by the other children at school; most people in Maycomb start looking at the Finches with suspicion; Atticus even has to put his physical wellbeing on the line to prevent a choleric mob from lynching his client. And yet, all along, even before the trial starts, one overarching argument comes to the surface: for the sake of justice, Tom Robinson’s story needs to be told.

No matter what anyone says or does, Atticus tells his children, don’t kick, don’t spit, don’t even insult anyone back, because in a world governed by laws, rational arguments must prevail over passionate exultations. Atticus knows that the first instinct of the vast majority of people in Maycomb is to be violent; he expects everyone to assume Tom Robinson to be guilty; he expects everyone to demand revenge. But he is also confident that once the dust of the emotions settles, the sheer weight of the facts will give them prominence against the background of so much speculation. This is not to say Atticus has any expectations about an all-white jury acquitting his client – he knows full well that he has not enough time in his hands to allow the dust to settle anywhere near enough to stand a chance of winning in court. But he still gives his all in a lost battle, just because it’s the right thing to do.

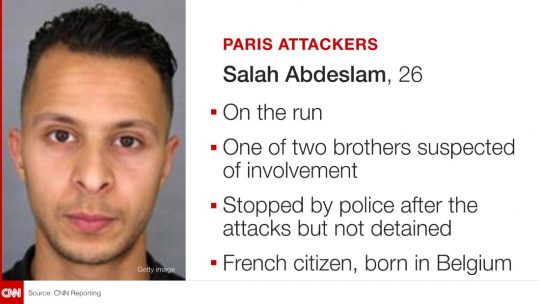

Atticus Finch is maligned by his peers, not so much because he is forced to defend Tom Robinson but because he wants to. That, however, is the full extent of the parallel between To Kill a Mockingbird and the drama that unfolded in Brussels following Abdeslam’s capture. Like Atticus Finch, Sven Mary wanted to represent this universally hated character: Mr Mary, it seems, had been contacted by Abdeslam’s family in January 2016, and he immediately made public his willingness to act on behalf of the runaway. But while Atticus is ready to defend the rights of a man who is being wrongfully accused of a crime he didn’t commit, Sven Mary was engaged by a man who was involved in a heinous bloodbath that claimed 130 lives, and who has been connected to another terrorist attack that killed thirty more people – a man whose ill intentions are way beyond reasonable doubt, and indeed, a man whose murderous delusions have long come true.

Though Atticus Finch and Sven Mary share a desire to defend the outcasts of their respective societies, the two of them stand at opposite ends of the spectrum in most other senses. For instance, one of the weaknesses of To Kill a Mockingbird might be how clear-cut Tom Robinson’s case is: not only is he crippled and consequently unlikely to have been capable of coercing his alleged victim, but he is also facing a trial against the most vulnerable element in Maycomb, bar the black population. Uneducated, inbred, amoral, and hopelessly poor, the Ewells are regarded by just about everyone in town as the lowest form of white life – white trash, quite literally – which enables Atticus to build a case of sorts. Had Tom Robinson been accused of raping any respectable member of Maycomb’s society, he would in all likelihood never have made it to the courtroom, and even if he had made it, his attorney would not have been allowed to call into question the other witnesses’ account of events. The only reason Tom Robinson enjoys the privilege of a fair trial (if not a fair sentence) is because he is up against a member of the nearest rung to his own on the social ladder – even if, ultimately, the gap between the two proves infinite, unbridgeable.

Evidently, this circumstance could not be further from the specifics of the case against Salah Abdeslam. Indeed, the situation is so different that Sven Mary indicated his client had no intention of claiming he wasn’t at the scene of the Paris attacks, and he even went as far as to say that he wouldn’t have been prepared to defend Abdeslam had he chosen to make that claim. There is no question that Abdeslam is a jihadist fighter; no doubt that he was part of the cell plotting and carrying out the attacks of 13 November 2015; no uncertainty regarding the innocence of his victims, the atrocity of his crime, or the extent of his involvement. So what’s the point in defending him? Why would Sven Mary have wanted the job in the first place?

The simplest and most cynical answer is, of course, that the notoriety the case was always going to bring. For better or worse, there’s no denying that the case made Mr Mary an international celebrity. But this explanation alone rings far too simplistic, and while the allure of fame might have played a role in his decision, there is something more pressing, something far greater, that needs to be taken into consideration.

Like every other suspect and perpetrator of the Paris and Brussels attacks, Salah Abdeslam is a second generation immigrant from a Muslim family. He holds a French passport through his Moroccan parents’ link to Algeria, but he was born in Brussels, he was raised in Brussels, he attended school in Brussels, he speaks with a Belgian accent, he committed his first misdemeanors in Brussels. By all standards, bar the most radically conservative, Salah Abdeslam is Belgian. Salah Abdeslam is as Belgian as J-Lo is American; he’s as Belgian as Charles Aznavour is French. Yet in some sense the problem is that he is as Belgian as Tom Robinson – whose ancestry is never touched upon in To Kill a Mockingbird – is American.

Atticus Finch defends Tom Robinson because his side of the story needs to be heard; Atticus Finch steps between the cell where Tom Robinson is kept and a crowd of people ready to take his life because, in a world governed by laws, there is no room for trial by mob. But Tom Robinson is a good man. Salah Abdeslam doesn’t deserve any leniency, he doesn’t deserve any consideration, he doesn’t even deserve to be heard. However, when Sven Mary told the press he was contemplating suing the French prosecutor for quoting from his client’s confidential statement, when he condemned the abuse of power entailed by describing his client as “public enemy number one”, Sven Mary was effectively stepping between Salah Abdeslam and the mob, because in a world ruled by laws there is no room for trial by media either.

The sad and thorny fact is that the vast majority of European societies continue to this day to struggle to avoid the pitfalls of discrimination, inequality, and social injustice in their dealings with the large immigrant communities that by now have come to be an intrinsic part of their fabric. For many years, ghettoisation was seen as a mutually beneficial arrangement both for newcomers and for “indigenous” members of European societies, which would then be able to coexist with little or no interaction necessary. For the migrant communities, this would satisfy a natural disposition to bunch up and create as similar an environment as possible to the one they’d left behind – after all, there’s safety in numbers and comfort in familiarity. Meanwhile, native communities would easily be able to avoid contact with these outsiders merely by staying clear of the areas where they were concentrated, habitually peripheral zones or rather undesirable destinations in the first place, be they Brixton, Finsbury Park, or Notting Hill for the West Indians from the Empire Windrush generation, or the area around the Hauptbahnhof in Munich for the Turkish guest workers, the Gastarbeiter, who were invited into Germany in the late 1960s and through the 1970s, to name but two notorious examples.

The problem with this approach took some time to flourish, but once it did it proved to be of monumental magnitude: in Germany, for instance, whole neighbourhoods became so uniformly Turkish that all shop names and at times even street signs were in Turkish, not German. The social and economic conditions experienced by these communities were also drastically disparate compared to the average “indigenous” community’s experiences: effectively being on the margins of society, these ghettoes were, and in many cases remain, prone to all sorts of adverse circumstances, from overcrowding to social exclusion, ideological, religious and cultural segregation, lack of opportunities, concentration of power on single members of the communities, the emergence of gang cultures, and so on. Yet, somehow, the general perception was that the immigrants enjoyed a privileged life in Germany, where they were after all employed and therefore entitled to free education and extensive healthcare, compared to what their lives would be like back in Turkey. The fact that there was widespread discrimination against them – not least with regards to Germany’s archaic citizenship laws – was not even considered to be a major issue until a generation of children born in Germany had grown to be neither Turkish nor German. In England the policy of ubiquitous social housing prevented the proliferation of vast ghettoes across large urban sprawls in the manner that banlieues came to surround most cities in France, but this alone is not a sufficient condition to create social cohesion. Racism, xenophobia, and resentment found as fertile a ground in Britain as elsewhere in Europe, partly due to the seriously trying period Britain’s economy went through from the mid 1970s to the early 1980s, but ultimately because in a fragmented society where you have your space and I have mine, where separate groups live their parallel lives without ever crossing paths, there will always be substantial issues of inequality which will eventually result in major conflict.

When Mother Merkel publicly acknowledged in 2010 that multiculturalism had proven an utter failure in Germany, she wasn’t so much sentencing the longstanding social policy to death as she was offering closure, a state funeral with all the pomp demanded by the occasion, to a notion that for too many years had reeked of obsolescence and decay. The academic establishment beat the political one to this realisation by over a decade, with the emergence of transcultural studies as a viable alternative to analyse the workings of cosmopolitan societies. Transculturalism places an emphasis on the human ability to feel empathy, given a series of shared or recognisable conditions, instead of enshrining the value of legacy and heritage central to traditionalist views. At its best, a transcultural society would emulate the dynamics of an irreversibly mixed one, something similar to the phenomenon prevalent throughout most of Latin America, where historical, demographic and social factors have confabulated to produce the ultimate hotchpotch in the form of mestizaje.

Because Latin America provides us with myriad different versions of deeply mestizo societies, we already know wherein lie the dangers of transculturalism, and what are its consequences. We know that economic factors are as important as cultural ones; we know that no society is colour-blind, no matter how heterogeneous it might be; and we also know that even in those societies that reach a relatively high level of colour-blindness, classism soon emerges as a similarly oppressive counterpart to racism. Most of all, we know that for transculturalism to really work, society at large must feel more positive about the present than about the past; it must disdain to some extent what came before and embrace with enthusiasm, with gratitude, the opportunities afforded to it by the present; it must, in many ways, be formed by exiles, emigrants, and castaways in search of a better future elsewhere. In this sense, perhaps Australia is better suited to face the challenges of the twenty-first century than we are.

But that is not a major problem either, for transculturalism isn’t an end in itself but rather an analytic tool to align and measure the success of the social policies that might erect the foundations of a more harmonious, fair, and equitable future. That is the true objective, a condition which cannot be imposed on people by laws or even by force, but rather a natural process that must necessarily take time, that must equally necessarily be consciously led in a given direction, and that ultimately ought to result in integration – the holy grail of modern life.

The problem with integration is that, if it is not to slip into assimilation, it will always produce changes, sometimes even substantial changes, in society. This, of course, is the unavoidable consequence of any influx of people into any previously established community, but while some might find this refreshing and enlivening, more conservative citizens find it threatening because they would ideally want to raise their children in an environment that is perfectly comparable to that of their own infancy, no matter how stagnant this might seem to others.

Integration entails shifting the weight of society even if just a fraction closer to the frame of mind of the minorities within it, in order to take care of their needs as if they were the absolute majority. This doesn’t mean society has to meet every minority halfway – that is neither reasonable nor, in all likelihood, feasible. It’s almost a simple equation of weight: societies are monolithic and not very malleable masses, so it’s quite reasonable to expect minorities to be more flexible, more adaptable, to do more towards achieving social harmony. But even concerning the responsibility that befalls minority communities in the effort to make integration successful, the extent and focus of their agency must be clearly outlined, monitored, and regulated by society from the start.

Over the past twenty years, these and other questions have been raised and revisited time and again in the seemingly futile diplomatic meetings where the future of the EU is regularly discussed. But then, like flotsam in the middle of the ocean, the issues go underwater again, only to resurface at a later stage with the same frustrating result. Haphazard attempts to come up with patchwork solutions to what are essential problems have often ended in moving the goal posts, sometimes even in the right direction. But today’s rules cannot be used to judge the behaviour of communities inscribed within a different legal and social arrangement. For instance, in Germany there is now an integration scheme that imparts free German language and culture lessons to migrants, surely a necessary and commendable initiative – but one that does not apply to the attitude of the Gastarbeiter of the 1970s, who chose to live in relatively small areas almost exclusively among themselves. Moreover, the results as well as the shortcomings of the strategies currently in force to prevent social fragmentation (and the discrimination that we now know inevitably comes with it) will only be fully evident in many years to come, surely long after the conservative party has lost its grip on power in the German political scene.

Harper Lee was conscious of the dangers of widespread discrimination within a society, and she made it clear through an oblique – if somewhat anachronistic – comparison between the condition of the African-American population in the deep South and the persecution of the Jewish population in Germany under Hitler’s Nazi regime. In this sense, there might be one more point of contact between Atticus Finch and Sven Mary: Atticus knows that Tom Robinson is doomed but he is willing to go through the ordeal of defending him in the hope that his case might change things, even if just a little. Similarly, Mr Mary must surely have been well aware that the book would be thrown at Salah Abdeslam, but ensuring that the rights of this cruelest of citizens were upheld meant that Mr Mary was actually safeguarding the rights of everyone, regardless of their ethnic backgrounds or faiths, regardless even of their crimes. Thus, in fact, neither Atticus Finch nor Sven Mary truly act on behalf of their clients – they are, ultimately, working towards the improvement of their, of our, societies.

In the current climate, the challenges posed by mass migration from drastically different cultures will only become greater and the long-term fate of the community quite likely hinges on its leaders’ abilities to respond to new and ever more pressing issues of social cohesiveness. Many are the attitudes that at one point or another will attract their share of the public limelight, especially in these times of extreme and often irresponsible demagogy. Yet, after all is said and done, to me it seems quite clear that integration is truly the only positive option, the only alternative which, rather than fear and hatred for the Other, carries hope for a more harmonious future.

— Montague Kobbé

.

Montague Kobbé (montaguekobbe.com) is a German citizen with a Shakespearean name, born in Caracas, in a country that no longer exists, in a millennium that is long gone. He is the author of the novels The Night of the Rambler and On the Way Back, both set in the Caribbean island of Anguilla, and in 2016 he co-edited Crude Words: Contemporary Writing from Venezuela, a collection of thirty texts by thirty Venezuelan authors – the first collection of its kind to be published in book format in the English language.

The stage adaptation of his bilingual collection of flash fiction, Tales of Bed Sheets and Departure Lounges, is set to début at London’s Cervantes Theatre as part of the inaugural Contemporary Latin American Writers Festival in 2017. He keeps a regular column in Sint Maarten’s The Daily Herald and has translated dozens of photography books with Spanish publisher La Fábrica.

.

.