.

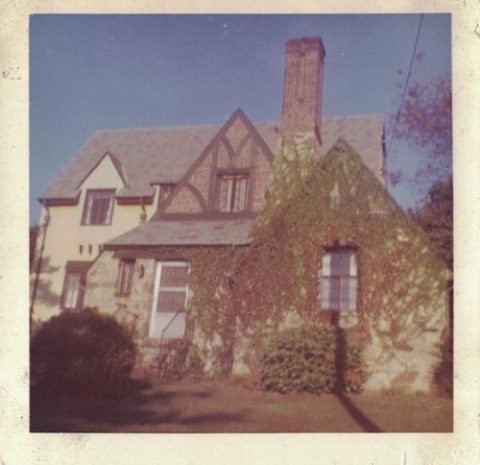

In the summer of 1962 my father was transferred to Atlanta when the small oil company he worked for was bought out by a rising giant, Tenneco. After only two years in the New York suburb of Mamaroneck, our stuccoed Tudor house, with its arched interior doorways, shag carpet, and library adjoining the living room, proved just another stage set, ready to be replaced. So much for the promised security and stability.

There was no question of my choice in the matter. In fact I welcomed the reprieve from a full-year sentence under sixth grade’s glowering disciplinarian, Mrs. Cohen, and looked forward to my first plane ride, the jet to Atlanta. By now I was becoming accustomed to the constant moves, revolving schools, goodbyes to friends.

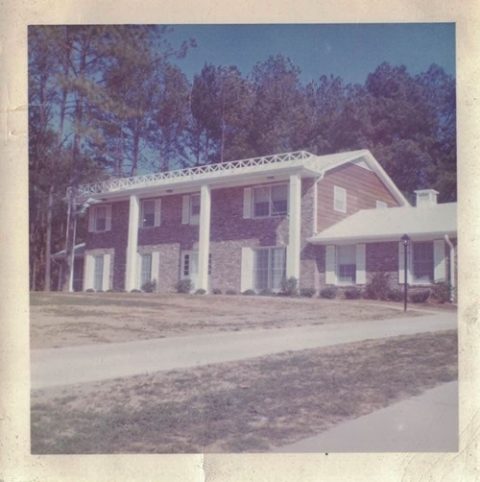

The New South was bustling with economic expansion and widespread Civil Rights activism. Atlanta was not a prime focus of the racial unrest, though it did serve as a magnet for new money. Housing developments and shopping centers sprouted like kudzu out of the impoverished countryside. My parents bought an antique-brick, colonial-style house in Sandy Springs, an expanding suburb north of the city. The house was barely finished, with no grass yet on the lawn—just hardscrabble red clay that clashed with the bright white columns of the façade.

Behind the house, dense pine woods stretched eastward, more or less undisturbed, all the way to Stone Mountain. Exploring the surroundings, I hiked up a ridge from where I could see the monolith in the distance, looming over the treetops—beckoning, I thought, like an ancient god, or shrugging like a gigantic gray Civil War monument. (The mountain face became precisely that a decade later when the Confederate Memorial Carving was completed, billed as the largest bas-relief in the world). A faint gray line traced the middle distance, a gravel road through the trees, with glimpses of black tarpaper roofs, snatches of radio music in the dusty breeze.

I turned back down the trail home, reflecting on how tenacious was the Civil War legacy, a full century after the fact. In my first week, I had visited the famous Cyclorama, a panoramic museum tribute to the Battle of Atlanta. Around the city, Confederate flags and memorial plaques kept the past alive. Meanwhile the Negroes, as we still called them, had not yet claimed their fair share of the American pie.

In the freshly constructed subdivision in Atlanta’s northern outskirts, I found a ready-made gang. I spent hours on the telephone flirting with Phyllis, Sandy, and Denise, or playing kickball with them and the boys, Mark and Gene and Jimmy, on a vacant lot. One day a bunch of us rode the bus downtown to wait six hours in line for a Beach Boys concert, where the girls screamed like all the other teenyboppers in the era of Beatlemania. We gathered on summer days at the neighborhood pool to swim, play water polo, plug the soft drink machine, and conquer the world at Risk. We learned to dance together, spinning records at Phyllis’s house, and on the slow songs, experienced that first thrill of two bodies pressed close. My new friends told me I talked like a Yankee.

Two new friends.

Two new friends.

Mark was a chunky, solid character, in the latter stages of puberty. He and I competed for the most authentic Beatle haircut. He taught me how to bowl. Together we would go on splurges, spending our lawn-mowing money on model kits for classic cars, James Bond or Tarzan books, and the latest hit singles. The cult of Davy Crockett was long gone; and “playing army” was no longer in vogue.

The Gulf of Tonkin incident was still two years away, and I was too young, or too preoccupied, to take seriously the threat to world survival when Kennedy outbluffed Khrushchev in that game of nuclear chicken called the Cuban Missile Crisis. No, my battles were fought with fist-sized classroom spitballs or in pickup baseball games on suburban lawns.

Younger sister Randall.

Younger sister Randall.

There were always two worlds represented in that housing development at the edge of the woods. My world faced front: the opulent, white-columned verandah of the ersatz mansion, the country club my parents joined, the lawns I mowed, the shiny new schools I attended, the neighborhood pool parties and ball games. The other view, out back, began in the shadowed glade with its bed of soft pine needles where my sister Randall and I would pitch a tent or play football one-on-one. The clearing faded into dreamy forest, where I stumbled one day upon a decaying and overgrown plantation house, a shaded pond (where I would later bring my father to fish for bass), and a little farther on, Barfield Road.

I had only once set foot on this long straight gravel road, peeking out from the woods. It was lined with a string of shanties, hardly visible but for half-hidden tarpaper roofs issuing thin columns of smoke, and clotheslines hung with bright patches of laundry. This was the Negroes’ road—the Negroes who never appeared on the front side of our nouveau-colonial house. Lying awake late on a Saturday night, I heard the roar of their drag races, muffled by the thick Georgia woods that stood between us. Theirs was a world apart—full of dark mystery, which in my ignorance I perceived as a kind of vague menace.

In sixth grade, I was introduced to “current events.” The savvy young teacher had us study newspaper reprints about Civil Rights actions all over the South. The South was rising again—this time in blackface. Atlanta was spared the more dramatic shootings and bombings, which would claim the lives of blacks and Northern sympathizers alike in Alabama and Mississippi. In 1964, Lester Maddox, a restaurant owner who later became state governor, would stand on an Atlanta street selling axe-handles to symbolize, and to enforce, his supposed right to bar blacks from his restaurant.

My father, long a sports and horse racing fan, respected black stars like Baltimore Colt halfback Lenny Moore and mingled with the integrated racetrack crowd as a matter of course. My mother in my early years had hired a black maid, as my grandmother still did. Dora, my mother told me years later, quit the day I asked her why her skin was black. Both my parents subscribed to the cliché: “They’re fine as individuals. It’s just as a race…” I listened curiously to James Brown on the kitchen radio, until one of my parents would complain about “those screaming n—s.” Even then, hearing them use that word, I found it offensive, but in my preadolescence so free of adult responsibilities, I could find no moral ground from which to offer a critique.

But one autumn day Mark and I were tramping around, kicking up piles of dead leaves in the woods beyond the subdivision. We heard voices—different voices. We looked up and saw dark figures darting along the ridge. Something whizzed and struck with a plupf into the leaves at Mark’s feet.

A calling card from the boys of Barfield Road.

“Hey, come on,” Mark said, his hackles up and voice cracking. “They’re throwing rocks. Let’s get ’em.”

Our naïve hearts beat war drums laced with fear. The boys we glimpsed through the trees appeared younger than we were. Did they have reinforcements?

Our first throws fell short. But this return fire piqued the interest of the fleeing strangers. They doubled back behind the ridge and lobbed a volley of stones over our heads. We couldn’t see them but could hear them shouting. More boys approached from the direction of Barfield Road: big brothers, little brothers. Mark and I retreated to within earshot of our paved road. We saw Jimmy Moore on his bike.

“Hey Jimmy!” I yelled. “We’ve got a rockfight in here, colored guys from Barfield Road. We need some help, there’s a bunch of ’em. See who you can round up, quick!”

A rock skimmed the pavement behind Jimmy’s rear wheel. He pedaled away, fast, shouting, “Okay, you got it!”

Mark and I stole back into the woods, using trees for cover and forcing back the more adventurous snipers. When our own reinforcements arrived, we engaged in an all-out fracas, with a gang of a dozen on the white side, and half again as many on the black—counting the little ones. We aimed for the bigger boys. Yelps and nervous laughs rang through the air.

Though the battle was drawn along the color line, the boys on my side displayed no vicious intent, racial or otherwise. Nor did I sense hatred from Barfield Road boys. The tenor of the fight was more like a spirited crosstown baseball match on a common sandlot. Except the opponents were utter strangers to each other.

We didn’t know where our black counterparts went to school, where they shopped, or where their parents worked. We avoided eye contact, recognized no faces and never learned their names. Meanwhile we knew the larger dimensions of social confrontation arrayed in the nation. This was a proxy war, a living cyclorama, fought for symbolic equality.

Never having experienced a rock fight before, I didn’t know how seriously to take it. Were they trying to hurt us? Unsure of any rules of engagement, I floated my rocks wide of any human victim and targeted smaller stones to sting an arm or leg. The trees themselves stood guard, protecting both sides.

After half an hour, our pitching arms grew too weary to carry on. The black boys melted back into the trees, their voices fading. The adrenaline of mock battle gave way to exhaustion, and we took stock, wondering how this all began and where it might have ended. There were no serious injuries on either side, as far as we could tell, and no ground gained or lost. The two stone-wielding armies drifted back to their separate worlds, never to meet again.

Except, that is, for the hair-raising encounter I dreamed that night. In those same, deep woods, on crackling dry leaves, suddenly a boot appeared, and higher up, big black hands holding an axe. That was enough—I awoke, heart pounding. Was he grim-faced, or smiling? I never saw his face.

Which more or less explains, with the benefit of hindsight, the larger problem of fear, hostility, misunderstanding, projection. In our dreams as in our lives, we act out the stereotypes we are given.

My mother the housewife, in suburban kitchen.

My mother the housewife, in suburban kitchen.

In three more years, my family would be gone from this place, too, back to hometown Baltimore, which straddled that contested middle ground between South and North. The landmark Civil Rights Act signed into law; Malcom X gunned down; the urban riots in Watts and Detroit; and the assassination of Martin Luther King. As a white family we remained buffered from racial violence and oppression, yet we were not immune to economic turbulence as my father toppled from his executive position to the ranks of the unemployed.

The reasons for his fall from grace were never entirely clear. Was it a corporate reshuffle, or, as my mother insisted with bitterness, the fault of his drinking? My older sister and brother already having fled the nest, Randall and I were left to go along for the ride, in our old ’58 Pontiac station wagon loaded like a dust-bowl jalopy. This time, bound for no upscale Tudor stucco, but a brick wilderness of row houses, all the same.

I took consolation in the opportunity to root close-up for my old baseball team, the Baltimore Orioles. By the time school let out for the summer of 1966, I had a new hero, black superstar Frank Robinson, who teamed up with established white star Brooks Robinson to lead the run for the team’s first championship. The bad news was, I turned sixteen, and my parents said I had to find a summer job.

My father had found work for another oil company, and my mother had re-entered the workforce as a secretary for an old family friend. I was attending a private Quaker school on a scholarship to make up for an academic history scrambled by too many moves. So getting a summer job wasn’t about the money. It was an obligation of manhood.

I fumed and despaired, argued and cried, wondered what in the world I would do. How could I find a job in a still unfamiliar city with no connections, no experience, no skills? So far I had only mowed lawns, raked leaves. My parents—they were together on this raw new deal—suggested I try the day job agencies where middle-aged black men lined up in the morning to be sent out on temporary work crews, doing manual labor in the oppressive heat and humidity for minimum wage.

So I walked the streets of the seedy Hampden district knocking on doors. It didn’t look like any business there could operate with margin for a new salary, even at a bargain rate. After a few dozen grizzled shopkeepers had scowled at my peach-fuzzed face, told me to speak up, and then sent me on my way, I lost all hope. Did I have too much of a Southern accent now?

Nor did my parents offer much sympathy. That night, talking it over with them in our basement den, I chose to voice my frustration by diverting attention to my father’s drinking, still a sore topic though he was working again. My mother did not take the bait; she saw through my stratagem. My father launched an angry tirade, only empty bluster, it seemed to me.

Six feet tall, he still had three inches on me, and fifty pounds; a barrel chest, broad back, and long thick arms. Imposing as any brute axe-man, his face I knew all too well. He was the old man, and I was bristling with adolescent self-righteousness—so I pushed him in the chest. He staggered a half step, glowered at me, and cocked his fist. My mother caught his arm. He huffed and puffed, a harnessed beast, as she shrieked at me to go to my room. I slipped away, still shaking. But my parents’ united stance carried a bitter justice: I would indeed have to make my own way in the world.

Next day I tried again to find work, knocking on more doors. Finally, a little humpbacked man with a weasel smile hired me to stock shelves and clean cages at a pet store a block from home. I would make a dollar twenty-five an hour, and feel grateful for it.

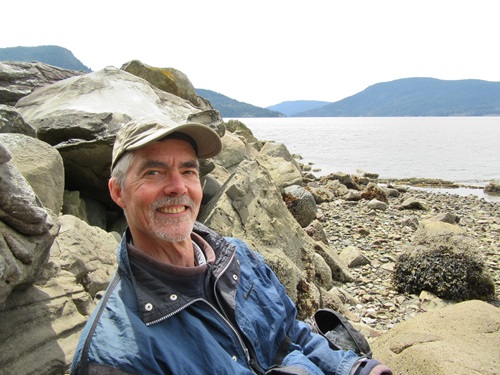

—Nowick Gray

.

Nowick Gray is a writer and editor based in Victoria, BC. The present text is an excerpt from a memoir of his nomadic youth in the Baby Boom generation, a quest for new roots. Educated at Dartmouth College and the University of Victoria, Nowick taught in Inuit villages in Northern Quebec, and later carved out a homestead in the British Columbia mountains, before finding the “simple life” in writing, travel, and playing African drums. Visit his website at nowickgray.com or Facebook page at http://facebook.com/nowickg

.

.