Clearly, Emmons is tired of literary stories that pretend at some kind of conclusive change with respect to character, whether that be in relationships, family, or matters of life and death…Each reading inspires visions and revisions. —Michael Carson

Josh Emmons

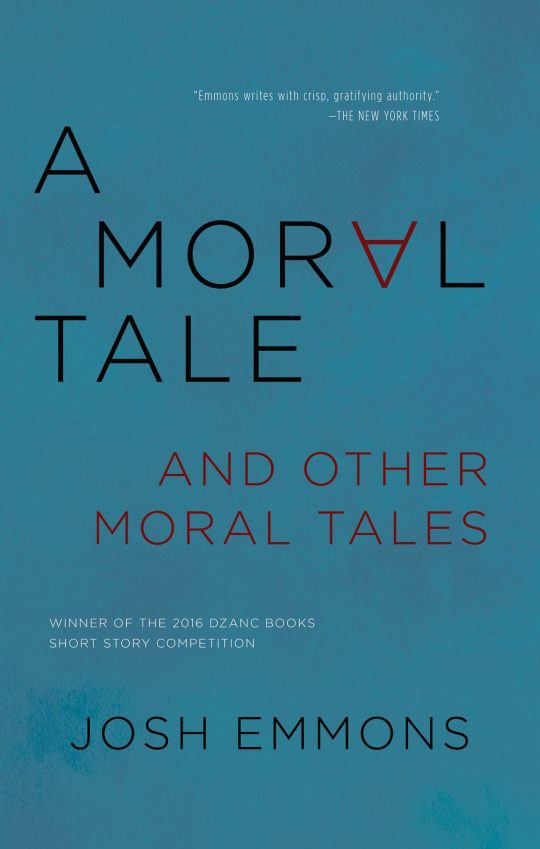

A Moral Tale and Other Moral Tales

Dzanc Books, 2017

184 pages; $16.95

.

Josh Emmons has a peculiar approach to literary sex. His first novel, The Loss of Leon Meed, follows a menagerie of eccentric characters haunted by a banal messianic vision. “Are you saying,” a married elementary school teacher asks her boss in the first pages, “that the only way I can keep my job is if I fuck you?” The principle stutters. “If that’s all it takes,” she says, before pulling down her underwear. His second novel, Prescriptions for a Superior Existence, features forced indoctrination, apocalyptic prophecy, and an anti-sex religious cult. In the opening pages the protagonist is shot for sleeping with the cult’s founder’s daughter.

The twelve short stories in the Iowa graduate and UC Riverside professor’s first short story collection, A Moral Tale and Other Moral Tales, dip even deeper into the delightfully bizarre and drolly promiscuous. They relate orgies, suicide epidemics, medieval warfare, Biblical floods, and Egyptian gods. Protagonists include stuntmen, cultists, nuns, tigers, child prostitutes, and a giant talking egg. Characters attempt to murder spouses and end up falling in love with them. They give up on a sex party and are killed in a car wreck on the way home. They get in arguments with Edenic snakes about tigerness. The sexual ministrations of shape-shifting women give them voice.

Yet for all this titillating fairy-tale whimsy, nearly all the characters seem to be chastely drowning. They come off of failed relationships. They have no direction. They wander in darkness. “The north of France is like the south of France,” says the first line of the collection’s first story. “The tiger stopped at a break in the rain and realized he was no longer on the path he’d been following,” opens a later story. “Nu,” the account of a betrayed wife hiding in a cabin in the woods, begins, “the stream behind Alice’s house fed into a river that led to the ocean.” A sense of similitude and ennui pervades even the most exotic settings. No difference and no point. Definitely no climaxes or climaxing. “There is no north, there is no north, there is no north,” repeats a medieval king at the moment of execution.

Emmons’ jeweled prose exacerbates this disjunction. Here is Bernard, the protagonist of the first story, “A Moral Tale”—the one that begins with “The north of France is like the south of France”—coming off a failed relationship and deteriorating career prospects, living in his cousin’s apartment, judging her for being lazy and drug-addled, and ignoring her insistent requests to set him up with Odette, a friend of hers:

Bernard went to bed and for an hour heard laughter coming from the living room television, then forty minutes of panting, then a long, low-grind blender. He kept on flipping his pillow over to get to the cool side. Eventually it became morning and he took a walk on sidewalks slick with black ice and saw that in this part of the city what broke and was abandoned stayed broke and abandoned. The cold made it all throb in place. He passed empty storefronts and Halal butchers and Gypsy kids selling iguanas and block-long souk with spices like varicolored dunes rippling across linked tables.

Sentences pivot from simple cumulative lists to simple subject-verb-direct object sentences and back to cumulative lists. The effect is that of a slow drip, a terrible occlusion of grays at odds with all those sharp cracks and abrupt shifts that pop around characters like fireworks (whether they be of others masturbating, feudal political-strategizing, or Emmons’ reliable humor). Often the protagonists feel stuck in quicksand, sinking slowly, at a committed puritanical remove from baroque exigencies and St. Teresa ecstasies.

Bernard from “A Moral Tale” moves back into life, into color and noise and warmth, but not in the way the reader might expect. He does not fall for the girl with the mysterious scar across her throat at church. He does not even fall in love with Odette, the girl his cousin wants him to sleep with. Instead, when Odette and Bernard are alone in a room, with him lying on two beanbags and she in bed, Bernard spells out the dramatic incidents and clever dialogue that will not take place; Bernard also baldly states his problems, the story’s ostensible “climax”:

She rubbed her arms and her nightgown didn’t slip down her shoulders. She didn’t sigh or propose that they work on linear equations or say, Bernard, I’m going to tell you something you already know but won’t admit, although if you did then a lot of what’s wrong here, like you lying on those stupid bean bags when I’m cold and alone on a huge mattress, and your having invented that text from your friend, and your unmerciful speech to Veronique about fraud might be fixed: your aunt didn’t ask you to move in with your cousin because she thought you could save her. On the contrary.

Bernard abruptly gets up from the beanbags and goes over to Odette’s bed. As he adjusts to the darkness, “Odette came into view as gradations of black and clothes, he saw, without surprise, with a kind of relief, that what lay beneath the surface was just a darker version of what lay above.”

After the night in bed with Odette, Bernard gets high with his cousin in a park and calls the girl with the scar on her neck to tell her he is watching a mime. The girl asks if this is the kind of mime that pretends to be trapped inside a box. He says that this one doesn’t do that. No one speaks. Wind comes from the west.

Then there are the stories where the characters do not get up and go to bed with Odette, stories where the characters realize too late that they should have. “BANG” is of this variety. It relates a worldwide suicide epidemic from the perspective of a character already given to suicidal thoughts pre-dystopia. Like “A Moral Tale,” the protagonist has the opportunity to go into the bed of someone else. But, unlike “A Moral Tale,” the protagonist backs away in horror from the opportunity. She resists for fear of what her mother might think. She fears the man’s age, his previous marriage, intimacy and the self-redefinition it requires. Now the roommate is dead. The protagonist missed her chance to become someone else. “BANG” concludes on a rooftop. The naked protagonist looks down at rectangular, boxy cars. Its final unpunctuated line—“she aimed a tentative”—returns the reader to the story’s very loud title.

Finally there are those like “Jane Says,” stories somewhere in between, with characters watching on as another rejects sex and with it life. It begins with characteristic drollery: “People say what a tragedy when you are thirteen and selling it on the street.” The thirteen-year-old prostitute-narrator then complains of the janes who pick him up who don’t really want sex—“the sick sad deviants who made you wonder even though you were a prostitute what happened to them.” He doesn’t mind the sex, he says, what freaks him out is pretending to be some jane’s dead son. “It was the pitiable,” the thirteen-year-old prostitute complains, “pitying the pitiful.”

Later in the story, a new jane picks up the narrator. She drives him to the woods and signs her worldly possessions over to him. “People use you and don’t see you for who you really are,” she tells him, “and it’s that way with all of us.” She leaves him in the car, walks into the woods. A sharp crack follows. “Lady!” the boy yells. “You got to take me back to the city.” He flounders about in the darkness. He falls. He asks for her in a whisper, quietly, “as though speaking softly would close the space between us, as though about existence she’d been wrong.”

Emmons writes tightly knit, engaging plots. Each phrase, paragraph, and scene carefully reticulates into the next. His prose is uniformly eloquent, clean and precise. The stories have meticulously considered desire-resistance patterns. But these are not simple, straightforward literary short stories. Neither are they strict moral tales as the title suggests. The often passive, sexually chilly characters do not change or reveal character so much as try to do everything they can to disguise it and forestall revelation. Pair this with fantastic environments and whimsical humor, and many of these stories left me with an odd sensation, as disoriented as the characters themselves.

This is not a criticism. Maybe it’s the point. Clearly, Emmons is tired of literary stories that pretend at some kind of conclusive change with respect to character, whether that be in relationships, family, or matters of life and death. In a recent interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books, Emmons said that many of the characters in A Moral Tale are stuck on the idea of themselves they don’t want to give up because the cost would be too high. “We have to keep revising our understanding of ourselves forever,” Emmons said, “and this is okay.”

The same could be said of not just the characters but also the curious stories in this curious collection. They do not lend themselves to easy analysis or classification. Each reading inspires visions and revisions. What they have to say, their “moral,” comes—if it does at all—in whispers, as though speaking softly might close the distance between Emmons and the reader, as though about both moral tales and literature we all have been wrong.

—Michael Carson

N5

Michael Carson lives on the Gulf Coast. His non-fiction has appeared at The Daily Beast and Salon, and his fiction in the short story anthology The Road Ahead: Stories of the Forever War. He is currently working towards an MFA in Fiction at the Vermont College of Fine Arts

N5