Though primarily known for his haunting, enigmatic novel Pedro Páramo and the unrelenting depictions of the failures of post-revolutionary Mexico in his short story collection, El Llano en llamas (The Plain in Flames), Juan Rulfo also worked on various collaborative film projects and his powerful interventions in the areas of documentary photography ensure that he continues to inspire interest worldwide. One hundred years after Rulfo’s birth (May 16, 2017), Deep Vellum Publishing will release The Golden Cockerel and Other Writings. This momentous publication includes the first ever translation of Rulfo’s second novel alongside fourteen other short texts. Numéro Cinq is proud to present this conversation between Dylan Brennan and translator Douglas J. Weatherford (both Rulfian scholars). Excerpts from four of the texts are also included below.

Dylan Brennan (DB); Douglas J. Weatherford (DJW)

DB: The Golden Cockerel and Other Writings has been selected by BBC Culture among their ‘Ten Books to Read in 2017’ and by The Chicago Review of Books among the ‘Most Exciting Fiction Books of 2017’s First Half’. Are you surprised by these accolades? Why is this book generating such interest?

DJW: I am pleasantly surprised by the early interest in The Golden Cockerel and Other Writings. Juan Rulfo (1917-1986) is one of the most important Mexican and Latin American authors of the twentieth century and yet in the English-speaking world he has seldom received the attention that he deserves. I believe the book is generating interest for several reasons. First and most importantly, Juan Rulfo is a big deal. His most iconic books —The Plain in Flames (1953) and Pedro Páramo (1955)— were innovative tours de force that challenged narrative forms and helped usher in the so-called “Boom” of Latin American literature that would include such renowned writers as Carlos Fuentes (Mexico), Julio Cortázar (Argentina), and Nobel laureates Gabriel García Márquez (Colombia) and Mario Vargas Llosa (Peru). I’m sure it helps that many around the world are remembering Juan Rulfo on this year, the centennial of the author’s birth. It’s also possible, I suppose, that some —hopefully on all sides of the political isle— are looking for ways to build bridges with Mexico to counteract the tensions of the current political environment. Ultimately, I believe that The Golden Cockerel and Other Writings is an exciting publication for English-language audiences. For those readers already familiar with Juan Rulfo, it offers the opportunity to explore his work beyond Pedro Páramo and The Plain in Flames. For others, I hope that this anthology will serve as an introduction to one of Mexico and Latin America’s most beloved writers.

DB: The myth that Juan Rulfo’s artistic output amounts to just two books and a few photographs still persists. Why is that? Where have these texts been hiding all these years?

DJW: They’ve been hiding in plain sight, as I’ll explain in a moment. The myth is very attractive: that Rulfo came out of nowhere to publish two books of fiction in rapid succession before abandoning the craft, overwhelmed perhaps by the weight of his own success. It’s a fascinating tale and one that has been repeated for so long that many are hesitant to let it go. Indeed, it’s the version that I learned as an undergraduate major of Spanish in the mid-1980s. But it’s also a fabrication that diminishes the valuable contributions that Rulfo made as a semi-professional photographer and as a writer in the Mexican film industry. Additionally, it ignores the existence of The Golden Cockerel (El gallo de oro), a second published novel that routinely and unjustly has been marginalized from the Mexican author’s literary canon. Indeed, the exclusion of The Golden Cockerel has been so complete that, until now, no full translation had appeared in English. Although authored most likely between 1956 and 1957, The Golden Cockerel wasn’t published until 1980. That delayed release, combined with the text’s often misunderstood connection to film, led many Rulfo critics and aficionados to disregard the novel. The Fundación Juan Rulfo reprinted El gallo de oro in 2010 and, since then, has offered two commemorative editions that package the author’s novels and anthology of short stories together, a move that draws attention to the significance of The Golden Cockerel. My translation of this second novel is paired with fourteen additional texts (plus a summary of the novel that Rulfo wrote). All of these items have appeared previously in print (many of them posthumously), but never included in The Plain in Flames. Some are well known, others much less so, but all bear witness to the same creative demons that define Rulfo’s literary output.

DB: What is The Golden Cockerel‘s connection with the cinema and in what way has that connection led to its marginalization?

DJW: That question was at the heart of an introductory essay that I wrote to accompany the 2010 release of The Golden Cockerel.{{1}}[[1]](“‘Texto para cine’: El gallo de oro en la producción artística de Juan Rulfo.” El gallo de oro. By Juan Rulfo. Mexico City: Editorial RM).[[1]] It’s clear that the decision —made most likely by Jorge Ayala Blanco and not Rulfo— to publish The Golden Cockerel in 1980 as a film text (“texto para cine”) had a deleterious effect on the novel’s reception. It also didn’t help that the piece was released sixteen years after Roberto Gavaldón adapted it to film (El gallo de oro, 1964). In that context, many simply began to refer to The Golden Cockerel as a film script, a denomination that is still heard frequently. To this day, in fact, there are some bookstores in Mexico City that incorrectly shelve the novel next to printed screenplays. As such, most researchers who have written about The Golden Cockerel have felt an obligation to address its generic classification. And, in an attempt to free the novel from its mislabeling, many of those individuals have tried to fully divorce The Golden Cockerel from its filmic roots. My preference is to affirm the piece’s identity as a novel while celebrating its very real connection to the Mexican film industry. Rulfo was a film enthusiast who, in the mid-1950s, was hoping to find additional creative and financial opportunities in cinema. Indeed, it is likely that Rulfo wrote The Golden Cockerel precisely so that it could be adapted as a film script, a task that ultimately fell to Carlos Fuentes and Gabriel García Márquez. In the end, I think that it is appropriate to acknowledge the cinematic origins of The Golden Cockerel while reading it as what it is: the second published novel of one of Mexico’s most celebrated writers of fiction.

DB: In addition to Rulfo’s second novel, you have included fourteen other texts in this book. How did you go about selecting which texts to include?

DJW: My original idea was simply to translate the three texts that were published together in 1980: The Golden Cockerel, “The Secret Formula,” and “The Spoils.” I discarded that idea quickly, however, realizing that it would be a mistake to perpetuate the mislabeling of The Golden Cockerel as a film text. It would also have been, I believe, a missed opportunity to promote other Rulfo writings that have never appeared in English or have done so but only in limited release. Will Evans of Deep Vellum Publishing was very interested in an expanded collection. Víctor Jiménez, the director of the Fundación Juan Rulfo, was more cautious and became convinced only when it was clear that we could build a collection that would have a strong thematic unity while offering an interesting reflection on the creative world of Juan Rulfo through texts that, although lesser known, already existed in print. There were three of us primarily involved in the selection of texts: myself, Víctor Jiménez, and Juan Francisco Rulfo, the author’s oldest son. The anthology includes a number of short pieces that, despite never appearing in The Plain in Flames, have circulated widely and are generally acknowledged as part of Rulfo’s canon: “The Secret Formula,” “A Piece of the Night,” “Life Doesn’t Take Itself Very Seriously,” and “Castillo de Teayo.” Another item, a letter that Rulfo wrote in 1947 to his then fiancé, was published in 2000. The remaining items —ten narrative fragments— are less definitive in their generic and canonic identity and have appeared almost exclusively in Juan Rulfo’s Notebooks{{2}}[[2]]Los cuadernos de Juan Rulfo. Transcription by Yvette Jiménez de Báez. Mexico City: Era, 1994[[2]], a unique gathering of Rulfo’s unpublished —and, in many cases, unfinished— writings, authorized by the author’s widow. The texts of Juan Rulfo’s Notebooks are eclectic in nature and include early drafts of Pedro Páramo, fragments of a film script, portions of two novels that the author began and never completed, and other experimental writings. The nine items selected from this collection are unique creative explorations that fit well into Rulfo’s literary canon and exhibit clear narrative structures that allow them to be read as independent, story-like texts.

DB: We’ve seen many examples of posthumous publications, most recently a “new” Bolaño novel appeared in late 2016. These are not always well received. Then again, sometimes we get Kafka or Dickinson. Were there any ethical concerns or worries associated with publishing work that Rulfo himself had chosen not to during his lifetime and, if so, how were these addressed?

DJW: The Golden Cockerel is not a posthumous publication, of course. But our decision to pair it with additional texts, some of which Rulfo never published, can certainly be perceived as controversial. And I was constantly aware of the responsibility of working with an author, like Juan Rulfo, who was self-critical and often hesitant to send items to press. I was encouraged, to be sure, to be working so closely with the Fundación Juan Rulfo and with members of the Rulfo family, and to be selecting only texts that already exist in print. Additionally, Víctor and Juan Francisco liked the selection of texts that we came up with so much that they decided to create a version in Spanish. That edition, titled El gallo de oro y otros relatos (Editorial RM), appeared at the beginning of this year. But returning to your question, the most poignant response might come from Rulfo’s widow, Clara Aparicio de Rulfo, who faced the same controversy when she decided to release Juan Rulfo’s Notebooks. Indeed, I mention her reply —tender in its tone— in my introduction to The Golden Cockerel and Other Writings. Clara explains that she resisted the temptation to conceal her husband’s working papers out of a responsibility to share the valuable writings (“so full of him” as Clara writes) that her husband left in her care. Ultimately, I hope that readers will see The Golden Cockerel and Other Writings as a valuable and respectful collection that, as I write in my introduction, “bears witness to Juan Rulfo and deserves to exist because each text is ‘so full of him.’”

DB: The Golden Cockerel had never been published in English. The same can be said for some of the other fourteen texts. Like most worthwhile tasks, translation can be as frustrating as it is rewarding. What challenges did you face when translating these texts? I’m particularly interested in specific problems and your strategies for overcoming these issues.

DJW: That’s an interesting question since I have long felt that Rulfo’s first novel, Pedro Páramo, is tough to translate to English. Margaret Sayers Peden offers a strong version (Grove Press, 1994) that, nonetheless, seems not to reach the poetic, experimental, and mythic heights of the original. The Golden Cockerel is an easier exercise and yet not without its own challenges. This second novel is more oral, less polished, and less mythic than Pedro Páramo, and it is less experimental than the stories of The Plain in Flames. In The Golden Cockerel Rulfo uses long sentences, abundant punctuation, and numerous short paragraphs. All of these characteristics feel natural (if perhaps less formal) in Rulfo’s original, but can seem awkward in translation. I found myself shortening a few sentences and lengthening some paragraphs, all the while struggling to balance a desire to conserve Rulfo’s unique voice but making the text more comfortable to English-language readers. Another interesting issue that I confronted was whether to translate a nickname given to Bernarda Cutiño, the primary female protagonist of The Golden Cockerel and one of Rulfo’s most memorable women, standing alongside the remarkable Susana San Juan of Pedro Páramo. Bernarda is known as La Caponera, a polysemic label that is complex even in the original Spanish. One writer (Alfred Mac Adam) who translated a few pages of the novel rendered the term into English as Lead Mare, referring to the horse that is placed at the front since other animals tend to follow it. The choice is not inaccurate, of course, but feels awkward. I decided to conserve the original —La Caponera— untranslated and italicized, allowing the reader to discern the label’s meaning through the narration’s context, much as Rulfo does in Spanish.

DB: What led you to study, research and, ultimately, translate the work of Juan Rulfo? Why should Rulfo still be read in 2017?

DJW: One of my primary research endeavors of the past decade has been to better understand Juan Rulfo’s connection to the Mexican film industry. As part of that project, I have worked extensively with The Golden Cockerel (including its two film adaptations) and became convinced that the novel deserves a wider audience. I found it baffling and frustrating that the novel —sixty years after its composition and nearly thirty years after its publication— had never appeared in English. In other words, I wasn’t a translator looking for a project; rather, I was a Rulfo devotee who noticed a void and felt a certain obligation to make this significant novel available to English-language readers. My efforts were, in many ways, a clichéd “labor of love” that became a truly enriching personal and professional journey through Rulfo’s lesser-known writings. Indeed, I hope that the reader of this anthology will approach these texts with the same excitement that defined my own exploration.

.

The Secret Formula

The truth is that it’s difficult

to get used to hunger.

And although they say that hunger

when divided among many

affects fewer,

the only true thing is that here

each one of us

is half dead

and we don’t even have

a place to lie down and die.

As it seems now

things are going from bad to worse

None of this idea that we should turn a blind eye to

this matter.

None of that.

Since the beginning of time

we have set out with our stomachs stuck to our ribs

while hanging on by our fingernails against the wind.

.

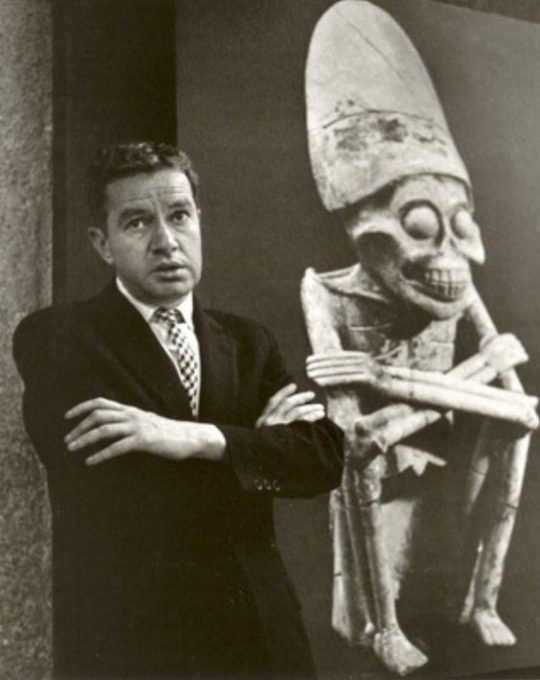

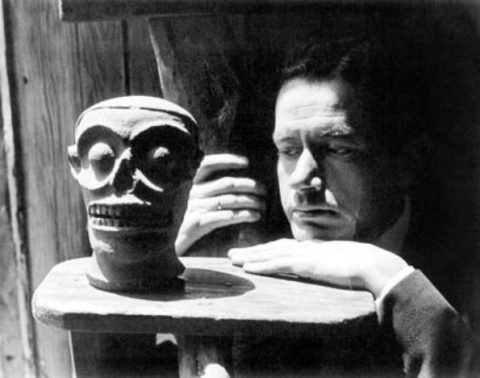

Totonac idol in Castillo de Teayo, c. 1950 (J. Rulfo)

Totonac idol in Castillo de Teayo, c. 1950 (J. Rulfo)

DB: Can you tell us a little about the Rubén Gámez film that this poetic text originally accompanied? Did Rulfo see the footage first and then write the text or vice versa? Is this a poem, a monologue for cinema or something else? Does The Secret Formula alter when divorced from the cinematic images? In what way? It seems, at least, to me, to be a text that is still painfully relevant today. Do you agree? Why?

DJW: “The Secret Formula” is unique among Rulfo’s writings for its poetic structure and for the way it came to exist. Rulfo wrote the text at the invitation of Rubén Gámez who used it as a voiceover narration to accompany portions of his experimental film by the same title (La formula secreta, 1964), an allusion to the ingredients of Coca Cola and a critique, among other things, of the influence of the United States on Mexico. According to Gámez’s widow, Rulfo’s participation in the film came about after a chance encounter in an elevator. Rulfo had somehow seen portions of the still-in-production film and, meeting the director for the first time, expressed his enthusiasm for the project. Gámez, on the spur of the moment, invited the novelist to provide a written text to incorporate in the film. Rulfo seems to have written “The Secret Formula” very quickly and, although it is possible that someone other than the author gave the text the form with which it is now associated, it’s clear that Rulfo produced something more akin to poetry than to narrative (although your suggestion that it might be read as a “monologue for cinema” is not off the mark). There is no doubt that Rulfo’s text can be read independent of Gámez’s film or that it fits comfortably within the author’s literary canon. And yet I highly recommend that readers seek out La formula secreta by Gámez to see how seamlessly Rulfo’s text is incorporated into the experimental, dialogue-free vignettes that make up one of Mexico’s most significant independent films. Finally, I absolutely agree that “The Secret Formula” continues to be relevant. Rulfo imagined the piece as a lyrical response to the marginalization and suffering of Mexico’s poor —whether at home or abroad as immigrants— who, in biblical tone, demand to be seen and heard.

.

Castillo de Teayo

A pale, yellowish gleam appeared in the east, revealing the outlines of everything. Meanwhile, on the side of the mountain, the world remained gray, increasingly gray and invisible.

Then, right in front of our eyes, was the Castillo. Its shape was strange in its seclusion, still undisturbed by any sign of life. It was surrounded by a mist that rose like steam from the humid earth and the dampened walls smoothed over with moss. With the moss covered in dew. That’s what we saw.

Night had come to an end.

That’s when that guy appeared, tall, thin, with his shirt open and a beard swarming around him in the wind. He stopped in front of us and began to speak:

—This is where the gods came to die. The banners were destroyed in the ancient wars and the standard-bearers fell to the ground, their noses broken and their eyes blinded, buried in the mud. Grass grew over their backs and even the nauyaca snake built its nest in the hollow of their curled legs. They’re here again, but without their banners, once again enslaved, once again guardians, now watching over the wooden cross of Christianity. They seem solemn, their eyes dull, their jaws dropped, their mouths open, clamorous beyond measure. Someone has whitewashed their bodies, giving them the appearance of the dead, wrapped in shrouds and ripped from their graves.

.

Female figure in Castillo de Teayo, c. 1950 (J.Rulfo)

Female figure in Castillo de Teayo, c. 1950 (J.Rulfo)

DB: Castillo de Teayo—You have described this text as ‘a travel narrative that often feels like a short story.’ Fictional memoirs seem very much in fashion these days. Do you think that its hybrid form contributed to its marginalization? There are various instances of critics attempting to see Rulfo’s photography as illustrative of his fiction, using quotations as captions and so forth and, therefore, neglected his photographic work that bears little resemblance to his prose. However, Castillo de Teayo seems to represent one of the few times when the photographs are meant to illustrate the prose. Would you agree? Why/not?

DJW: Juan Rulfo was fascinated by Mexico’s history and highways and his wanderings, especially in the early 1950s as a travelling salesman for the Goodrich-Euzkadi tire company, resulted in a number of photographs and travel writings, some of which were published during the author’s life. For example, Rulfo agreed to serve as editor for the January 1952 edition of Mapa, a travel journal sponsored by his company, and he likely visited the archaeological site of Castillo de Teayo for material to use in that publication. Although a selection of photographs from that trip would appear in the journal, the narrative text that he wrote was not included and would not appear in print until 2002. It’s true that some critics have tried to see Rulfo’s photographic endeavors merely as a reflection of the author’s literary output. Such a perspective is misguided, however. Rulfo, who developed a profound interest in the visual image as early as the 1930s, never intended to limit his creativity to the written word. In recent years, as more of his photography has appeared in print, Rulfo has gained a reputation as one of his country’s premier photographers. “Castillo de Teayo,” as you mention, is an exception to the rule as text and image combine to tell a story of a rich and vibrant pre-Colombian past that continues to define Mexico’s present moment.

.

A Piece of the Night

The guy who claimed to be Claudio Marcos had also become lost in thought. And then he said:

—I’m a gravedigger. Does that scare you if I tell you I’m a gravedigger? Well, that’s exactly what I am. And I’ve never admitted that my job pays a pittance. It’s a job like any other. With the advantage being that I have the frequent pleasure of burying people. I’m telling you this because you, just like me, should hate people. Perhaps even more than I do. And along those lines, let me give you some advice: don’t ever love anyone. Let go of the idea of caring for someone else. I remember that I had an aunt whom I really loved. She died suddenly, when I was especially attached to her, and the only thing I got out of it was a heart filled with holes.

I heard what he was saying. But that didn’t take my mind off of the quiebranueces, with his sunken, unspeaking eyes. Meanwhile, back here, this guy just kept prattling on about how he hated half of all humankind and how great it was knowing that, one by one, he would eventually bury all those he came across every day. And how when someone here or there said or did something to offend him, he wouldn’t get angry; rather, keeping his mouth shut, he would promise himself that he would give them a very long rest when they eventually fell into his hands.

.

Sculpted relief in Castillo de Teayo, c. 1950 (J. Rulfo)

Sculpted relief in Castillo de Teayo, c. 1950 (J. Rulfo)

DB: A Piece of the Night—Unlike most of Rulfo’s narrative fiction, this story is unmistakably urban. Rulfo lived in Mexico City for many years, yet rarely does it appear in his fiction. Why do you think that is? How is the city portrayed in this story?

DJW: Although associated so fully with Mexico’s rural towns and landscapes, Rulfo is seen more accurately as an inhabitant of Mexico’s largest urban centers. He was still very young, for example, when he was sent to live at a boarding school in Guadalajara after an assassin’s bullet claimed the life of his father. Eventually Rulfo would bounce back and forth between Guadalajara and Mexico City before settling permanently in his nation’s capital. So how does one explain Rulfo’s preference for rural spaces? Although there are multiple explanations, the one that I want to enumerate here is biographical. Pedro Páramo opens with a son who travels to the small town of his mother’s memories to search for a father that he never knew. That return to discover one’s enigmatic origin is, in Rulfo, as much biography as it is literary motif. Rulfo’s fascination with provincial Mexico —especially with the small towns of southern Jalisco where he was born— reveal a pained nostalgia for what Rulfo lost with the passing of his father. Although the scarcity of urban environments in Rulfo’s creative output is real, it can be overstated. As a photographer, for example, Rulfo shot a number of images in metropolitan settings. And he would place characters in urban environments in “Paso del Norte” and “A Piece of the Night.” This latter piece is a particularly touching witness to Rulfo’s interest in the city. Although read today as a short story, it is, in reality, a fragment of an urban novel, tentatively titled El hijo del desaliento, that the author was composing as early as 1940 before deciding to abandon the project. “A Piece of the Night” has long been one of my favorite Rulfo tales. Set in the rough-and-tumble Guerrero neighborhood of Mexico City (near Tlatelolco), the story follows the nocturnal wanderings of two life-weary protagonists, a prostitute and a gravedigger, as they search for shelter. With an infant in tow, the trio is connected archetypally and ironically to the Holy Family. A year ago, hoping to see how closely the story connected to the actual urban environment that Rulfo describes, I walked the same streets and plazas that appear in the story. It became clear that the author wasn’t interested solely in the metaphoric potential of his protagonists; rather, he was offering a very real portrayal of an actual city environment that he knew well.

.

Cleotilde

Where I don’t want to look is toward the ceiling, because up on the ceiling, moving from beam to beam, there’s someone who’s alive. Especially at night, when I light a small candle, that shadow on the ceiling moves. Don’t think it’s just a figment of my imagination. I know what it is: it’s the shape of Cleotilde.

Cleotilde is also dead, but not fully so. Even though I’m the one who killed Cleotilde. And I know that everything you kill, while you remain alive, continues to exist. That’s just how it is.

It’s been about a week since I killed Cleotilde. I hit her several times in the head, massive and hard blows, until she stayed good and quiet. It’s not like I was so mad that I was planning on killing her; but a fit of rage is a fit of rage and that’s the root cause of it all.

She died. Afterward, I did get mad at her for that, for having died. And now she’s after me. That’s her shadow, above my head, spread along the length of the beams as if it were the shadow of a barren tree. And even though I’ve told her many times to go away, to stop harassing everyone, she hasn’t moved from where she’s at, nor has she stopped looking at me.

.

DB: Cleotilde—This story was previously published in Los cuadernos de Juan Rulfo (Juan Rulfo’s Notebooks) in 1995. It reads like a finished story, as opposed to a fragment of an unfinished project. When was it written and was it originally meant to be part of a collection of stories that never materialized? It’s a brutal story of obsession and murder that I am particularly fond of. Why do you think it has still remained relatively unknown, despite having been published in Los cuadernos?

DJW: You are absolutely correct to read “Cleotilde” as an independent and polished short story. Indeed, I hope that the readers of my translation do just that and discover a remarkable tale that deserves a place among Rulfo’s other short fiction. And yet Yvette Jiménez de Báez included the piece in Juan Rulfo’s Notebooks in a section that she titled “On the Road to the Novel” (“Camino a la novela”), a classification that suggests a role as precursor to Pedro Páramo. To be sure, the violence and vengeance that define the narrative, along with its tormented apparition, the murdered Cleotilde, easily connect it to Rulfo’s first novel. Although it’s unclear exactly when Rulfo wrote this story or why he chose not to publish it, I don’t disagree with Jiménez de Báez’s decision to view it as a variation on the people, places, and themes that would eventually lead Rulfo to write Pedro Páramo. Although it’s true that “Cleotilde” has enjoyed only limited dissemination, it has appeared on the big screen as one of three stories that Roberto Rochín adapted to film in the feature-length Purgatorio (2008).

—Douglas J. Weatherford and Dylan Brennan

.

Editor’s Note: Excerpts and photographs appear here courtesy of the Fundación Juan Rulfo, Deep Vellum Publishing, and Douglas J. Weatherford.

.

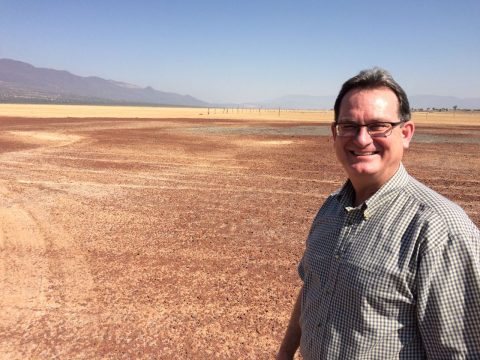

Douglas J. Weatherford at Laguna de Sayula.

Douglas J. Weatherford at Laguna de Sayula.

Douglas J. Weatherford is an Associate Professor of Hispanic American Literatures and Cultures at Brigham Young University (Provo, Utah). He has developed teaching and research interests in a wide range of areas related to Latin American literature and film, with particular emphasis on Mexico during the mid-twentieth century. Much of his recent scholarship has examined Mexican author Juan Rulfo’s connection to the visual image in film. Weatherford’s translation of Rulfo’s second novel El gallo de oro (The Golden Cockerel and Other Writings) will appear in May (Deep Vellum Publishing), the centennial of that author’s birth.

Dylan Brennan is an Irish writer currently based in Mexico. His poetry, essays and memoirs have been published in a range of international journals, in English and Spanish. His debut poetry collection, Blood Oranges, for which he received the runner-up prize in the Patrick Kavanagh Award, is available now from The Dreadful Press. Twitter: @DylanJBrennan

.

.