And Thee, across the harbor, silver-paced

As though the sun took step of thee, yet left

Some motion ever unspent in thy stride,—

Implicitly thy freedom staying thee!

from Hart Crane, “To Brooklyn Bridge”

A routine is a repetition that both breaks the day and places us in it, giving our lives the appearance of structure, of order. A bridge is a repetition of structural elements that orders a way beyond our routines, to thoughts of other things, or that appearance.

I have a routine where after the morning’s work I walk to the St. Johns Bridge and down to the Willamette River. If I miss a day my life feels incomplete. I live across the street from the playground of an elementary school and leave late morning to avoid the shouts and shrieks of the kids at recess, an inseparable mix of joy and chaos, though sometimes I take their noise with me. By that time I’m fatigued anyway, and bogged down in some unresolved disorder. I leave thinking the walk will provide inspiration, that I will return with fresh insight and rejuvenated resolve.

From the east entrance

I descend a side street

down to Cathedral Park, beneath the bridge, where north Portlanders run their dogs, fly drones, and get married.

Then, after following a long viaduct of approach,

I reach a small floating pier, beneath the span, and walk to its end, my terminus,

where I take a break—I have a bit of a climb back.

And I stand and look out on the river, and free my mind, and wait to see what comes, from without, from within.

Designed by David Steinman, an engineer of considerable reputation, the bridge was the result of local initiative and remains a source of civic pride and identity. Boosters staged vaudeville acts throughout Multnomah County to promote funding; images have since multiplied across St. Johns, on the banner of the neighborhood newspaper, on storefronts, on posted bills and t-shirts. Construction started a month before the Crash of ’29.

Yet while it set several records when built, the St. Johns Bridge is not well known and pales before more recent structures that move us to greater awe. Really, there was no compelling need to build it and it serves no large purpose now. The plan then was to connect the small industrial communities of Linnton and St. Johns, some five miles north of downtown Portland. Today it joins no major freeways on either side. But that is what I like about it, a modesty that encourages intimacy, that it is not especially useful, that it is largely there for itself, that it is distant from the noise of our wonder.

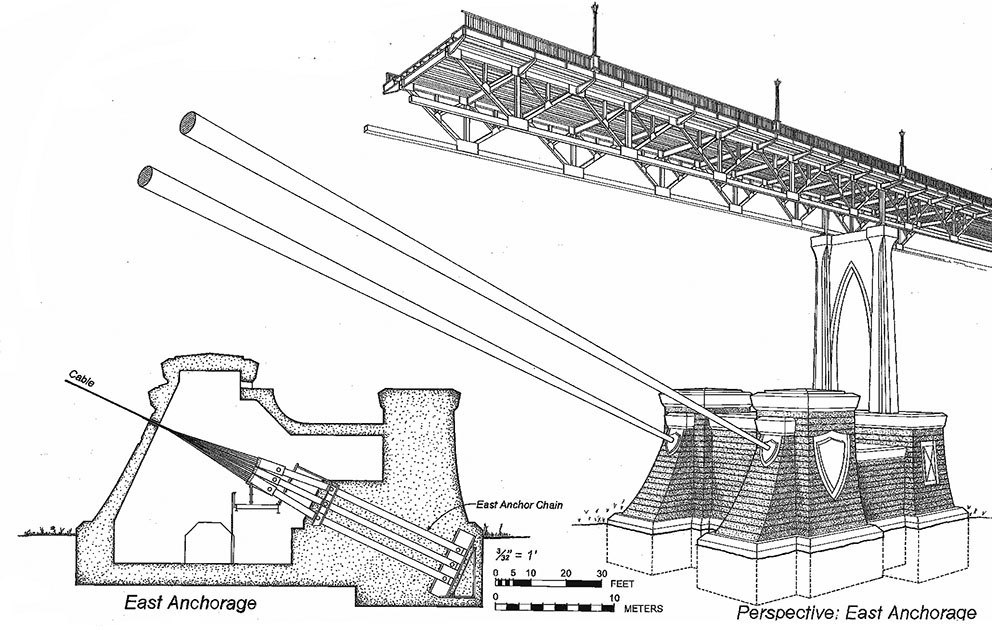

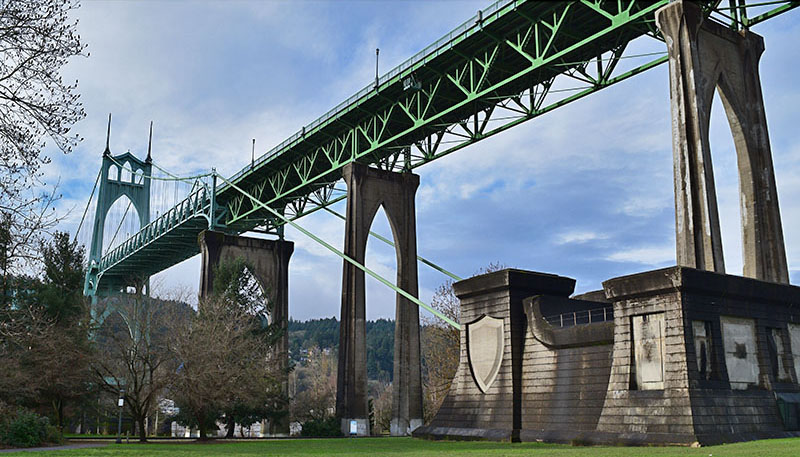

The east anchorage expresses its mass in a squat concrete structure, the energy of its function in steeply curved posts and buttresses, this function formalized in a compressed stance embellished with abstract emblems and stabilized and capped with cornice work,

the energy released in the ascent of the cables to the towers, the cables carrying a tension hard to imagine,

the tension easing into the sweeping curves of the cables that hold the deck. The suspense of anchorage discharges in the process of suspension. The bridge entire, in the arcade of concrete piers, the latticework of trusses supporting the road deck, the network of thin cables holding the deck from above, scarcely visible, in the division of bracing within the towers—is a complex orchestration of compression and tension brought together into a whole that is graceful, effortless, seemingly weightless, almost ethereal. To me, with my limited knowledge of engineering, such a feat isn’t possible and the bridge is simply marvelous. My spirits lift every time I see it.

The bridge was built at a time when the ruling esthetic demanded an honesty of structure, a welding of form to function, and Steinman spoke to the integrity of his design. But another desire, another wish, competed with utility, the American technological sublime, which complemented then supplanted the natural sublime once found in the American landscape. John Roebling’s Brooklyn Bridge carried the spirit, and Steinman, like Hart Crane, grew up in proximity and professed his close attachment, its influence.

Then there is the other spirit. The gothic arch, once used to elevate belief and bring in light, provides the motif played throughout, in the concrete piers and components of the towers, arches of varying width, height, and pitch. According to Steinman the pointed arch added contrapuntal tension to the rhythm of the suspending cables, but the structure he called “a prayer in steel” also brought past associations and higher thoughts. Today, maybe only nostalgia, and fading questions.

I’ve had a touch of vertigo the times I have walked across, however. That used not to bother me. Yet it’s two hundred feet down, and when I look out from the deck I feel the downward temptation. There is this about bridges as well, that they move us to the edge, to another launching point. In the movie Pay It Forward a woman climbs on its railing to make the leap but is saved by a recovering drug addict who walks by and talks her down.

Still, the bridge is always there, a point of continuity and stability, an anchor of connection and communication with, yet also of structural separation from, with, from nature that surrounds, its variations through the seasons, with, from the ambiguous, overcast moods of Portland weather that call for some kind of brightness, with my shifting thoughts, from the fog of my moods.

But only this is certain one day to the next: our structures are just structures, our function is undefined.

I wait at the end of the pier until I realize I am waiting. Nothing ever comes, in fact I put my work aside and let it drift. But I always get this release, this revelation: I am free and I am alive, and I don’t have answers to anything.

Very nice Gary. Thank you.

Hi Gary,

This is Bobby’s mother. He lives in your building. What a drag to be laid up with a broken leg. You have plenty of time to contemplate the world though, or to watch, “Who Wants to be a Millionaire?”. I am sorry to hear of your predicament and wish you well.

Gayle Hiester