To write poetry is to enter the golden room, the music of vowels and consonants and images. To love intently is to enter the golden room where there is a synthesis of two people. To mourn or grieve intently is to enter the golden room of memory and loss. —Allan Cooper

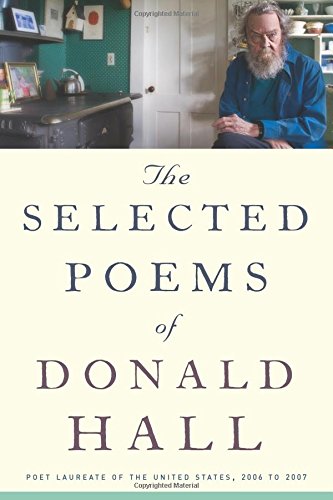

The Selected Poems of Donald Hall

Donald Hall

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015

160 pages; $22.00

.

When the British sculptor Henry Moore was in his 80s, Donald Hall asked him “Would you tell me the secret of life?” Moore replied, “To do what you want to do…” We can interpret what you want to do in many different ways, but I feel that Moore is speaking here about something more along the lines of Joseph Campbell’s “Follow your bliss.” For any artist, it means to follow your path as deeply and as intently as you can. There are no guarantees in the artistic life, and you have no idea of how far you will have to go, or how successful you will be in the end.

Hall was born in 1928 in Hamden, Connecticut. When he was 16, he met Robert Frost at the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, which consolidated his desire to become a professional writer. Early in his career he became the first poetry editor of The Paris Review; he also was co-editor of the ground-breaking anthology New Poets of England and America (1957). Hall has published over 50 books, including poetry, biographies, essays, plays, children’s books, memoirs and textbooks. His many awards include the National Book Critics Circle Award for Poetry (1988), the Frost Medal (1990) and the National Medal of the Arts (2010). In 2006 he was named Poet Laureate of the United States. He has lived for many years at Eagle Pond Farm in Wilmot, New Hampshire.

It’s important to include Hall’s second wife, the poet Jane Kenyon in this discussion of his work. Their move in 1975 to his grandparent’s farm in New Hampshire was a new beginning for both poets. As he has said, they sort of “camped out” to see what would happen. And what happened is that life on the farm and the landscape of rural New Hampshire nourished the work of both poets. Hall published his seminal work, Kicking the Leaves in 1978. Kenyon’s first collection, From Room to Room was published the same year. Before her death in 1995, Kenyon published four significant collections of poems, and one collection of translations, Twenty Poems of Anna Akhmatova, which appeared from Robert Bly’s Eighties Press. It was one of the first clear translations of Akhmatova’s work in English. Together, Hall and Kenyon were following their own bliss.

§

For some poets, doing what you want to do often means developing and deepening the concerns, themes and style of their early poems throughout a long career. There’s a certain tone to their work that deepens over time, but the tone is always familiar. Other poets, such as Hall, go through a more embryonic development—their style goes through radical shifts over many years. Hall’s voice is always consistent. One of the great joys of reading The Selected Poems of Donald Hall is that we have samples of the diverse styles of his poetry from the last sixty years in one slim volume. They include the early formal poems of Exiles and Marriages and The Dark Houses; the experimental poems of A Roof of Tiger Lilies, The Yellow Room: Love Poems and The Town of Hill; poems rooted in memory and a loved landscape in Kicking the Leaves and The Happy Man; the prophetic and socio-political concerns of the book-length poem The One Day; and the many poems he wrote for Jane Kenyon and his life with her.

In the “Postscriptum” to this Selected, Hall says “I’ve told the story before, how a grumpy stranger asked me, “What do you write about anyway?” I blurted out, “Love, death, and New Hampshire.” It’s true. Love, death, and love’s death—in early poems maybe love for death?—and always Eagle Pond Farm.”

I would add pleasure as well–the pleasure of a known landscape, love’s pleasure, and the inner room that two people build together, if they’re lucky. One of his early poems about pleasure came at a time when he was moving from formal verse toward experimental free verse:

THE LONG RIVER

The musk ox smells

in his long head

my boat coming. When

I feel him there,

intent, heavy,

the oars make wings

in the white night,

and deep woods are close

on either side

where trees darken.

I rowed past towns

in their black sleep

to come here. I passed

the northern grass

and cold mountains.

The musk ox moves

when the boat stops,

in hard thickets. Now

the wood is dark

with old pleasures.

This poem was quoted by Robert Bly in an essay on Hall’s poetry in the third issue of Bly’s poetry magazine, The Fifties: “This poem…suggests that the way out of the middle class is by a door the middle class cannot find—a secret life. The concept of the poet as a man with an inner life is, as we look back, the central quality of a poet as developed by Yeats, and the Spanish, and this image seems the one least developed in America.”

Hall further developed the idea of pleasure in the title poem of his collection Kicking the Leaves. One of the surprising elements of this long poem is that he perceives pleasure not as a rising energy, but a kind of falling. There’s a gravity to the poem that seemed to be absent in the early collections. Here is the final section of “Kicking the Leaves”:

7.

Now I fall, now I leap and fall

to feel the leaves crush under my body, to feel my body

buoyant in the ocean of leaves, the night of them,

night heaving with death and leaves, rocking like the ocean.

Oh, this delicious falling into the arms of leaves,

into the soft laps of leaves!

Face down, I swim into the leaves, feathery,

breathing the acrid odor of maple, swooping

in long glides to the bottom of October—

where the farm lies curled against winter, and soup steams

its breath of onion and carrot

onto damp curtains and windows; and past the windows

I see the tall bare maple trunks and branches, the oak

with its few brown weathery remnant leaves,

and the spruce trees, holding their green.

Now I leap and fall, exultant, recovering

from death—on account of death, in accord with the dead—

the smell and taste of leaves again,

and the pleasure, the only long pleasure, of taking a place

in the story of leaves.

If you read these lines out loud you can hear what he calls “the vowels of bright desire.” We say we fall in love with a person, a place, a thing, an idea, but falling—a submission—is always part of that love. His best poems are always a kind of submission. “Gold,” written earlier than “Kicking the Leaves,” carries the idea in a different way. Perhaps the act of giving up to another person creates something else, what he calls a golden room:

GOLD

Pale gold of the walls, gold

of the centers of daisies, yellow roses

pressing from a clear bowl. All day

we lay on the bed, my hand

stroking the deep

gold of your thighs and your back.

We slept and woke

entering the golden room together,

lay down in it breathing

quickly, then

slowly again,

caressing and dozing, your hand sleepily

touching my hair now.

We made in those days

tiny identical rooms inside our bodies

which the men who uncover our graves

will find in a thousand years,

shining and whole.

To write poetry is to enter the golden room, the music of vowels and consonants and images. To love intently is to enter the golden room where there is a synthesis of two people. To mourn or grieve intently is to enter the golden room of memory and loss. After Jane Kenyon died, Hall wrote “Letter with No Address.” Part of that poem is quoted below:

……………………………You know now

whether the soul survives death.

Or you don’t. When you were dying

you said you didn’t fear

punishment. We never dared

to speak of Paradise.

At five A.M., when I walk outside,

mist lies thick on hayfields.

By eight the air is clear,

cool, sunny with the pale yellow

light of mid-May. Kearsarge

rises huge and distinct,

each birch and balsam visible.

To the west the waters

of Eagle Pond waver

and flash through popples just

leafing out.

………………Always the weather,

writing its book of the world,

returns you to me.

Ordinary days were best,

when we worked over poems

in our separate rooms.

I remember watching you gaze

out the January window

into the garden of snow

and ice, your face rapt

as you imagined burgundy lilies.

I can’t imagine finer lines about a life lived well together.

§

Poetry, love and death are each a kind of letting go and a returning. Hall, who began writing formal poems, came back to them in recent years. Again, from his “Postscriptum”: As I read my poems in chronological order, I am aware of changing sounds and shapes. I move from rhymed stanzas to varieties of free verse, and later—out of love for Thomas Hardy’s poems—go back to meter again.” One of the strongest examples of his late poems is “Her Garden”:

…….I let her garden go.

…………………let it go, let it go

…….How can I watch the hummingbird

……………….Hover to sip

……………….With its beak’s tip

The purple bee balm—whirring as we heard

……………….It years ago?

……………The weeds rise rank and thick

…………………………let it go, let it go

…….Where annuals grew and burdock grows.

………………Where standing she

………………At once could see

The peony, the lily, and the rose

………………Rise over brick

…………….She’d laid in patterns. Moss

………………………let it go, let it go

………Turns the bricks green, softening them

………………..By the gray rocks

………………..Where hollyhocks

That lofted while she lived, stem by tall stem,

……………….Dwindle in loss.

§

In a 1971 interview with The Tennessee Poetry Journal, Hall talked about the kind of poem he would like to write:

I am mainly interested in trying to write a poem in which, as Galway Kinnell said to me in conversation last fall, you bring everything that you have done, everything that you know, together at once. That’s not quoting Galway exactly, that’s what I got from what he said. That kind of poem involves knowing yourself. You have to be able to get at the truth of your feeling and not to distort it. This is where I want to go now, and where I hope I am going.

He might not have known at the time that it would take a lifetime to write that kind of poem. He first published “Affirmation” in The New Yorker on May 21, 2001, when he was in his early 70s:

AFFIRMATION

To grow old is to lose everything.

Aging, everybody knows it.

Even when we are young,

we glimpse it sometimes, and nod our heads

when a grandfather dies.

Then we row for years on the midsummer

pond, ignorant and content. But a marriage,

that began without harm, scatters

into debris on the shore,

and a friend from school drops

cold on a rocky strand.

If a new love carries us

past middle age, our wife will die

at her strongest and most beautiful.

New women come and go. All go.

The pretty lover who announces

that she is temporary

is temporary. The bold woman,

middle-aged against our old age,

sinks under an anxiety she cannot withstand.

Another friend of decades estranges himself

in words that pollute thirty years.

Let us stifle under mud at the pond’s edge

and affirm that it is fitting

and delicious to lose everything.

To lose everything. As we age, there is the thinning out of things. People that we have known well and loved leave us, or die. But there is still the residue of love, alive in the great sounding box of memory:

Ordinary pleasures, contentment recollected,

blow like snow into the abandoned garden,

overcoming the daisies. Your blue coat

vanishes down Pond Road into imagined snowflakes

with Gus at your side, his great tail swinging.

( from “Weeds and Peonies”)

Donald Hall has said that he will write no more poems. In a long life of poetry he has written a dozen or two of the best poems of his generation. What do we expect from any poet? We carry lines of their poems with us, sometimes whole poems in memory. They rise mysteriously inside us when we need them the most. They comfort us and feed us, bring resolution to our grief, our loss, or affirm our joy and deepest convictions. Whether he writes more poems or not, he has given us many gifts. I’ll let these lines from his poem “The Master” have the final say:

When the poet disappears

the poem becomes visible.

What may the poem choose,

best for the poet?

It will choose that the poet

not choose for himself.

–Allan Cooper

N5

Allan Cooper has published fourteen books of poetry, most recently The Deer Yard, with Harry Thurston. He received the Peter Gzowski Award in 1993, and has twice won the Alfred G. Bailey Award for poetry. He has also been short-listed three times for the CBC Literary Awards. Allan intermittently publishes the poetry magazine Germination, and runs the poetry publishing house Owl’s Head Press from his home in Alma, New Brunswick, a small fishing village on the Bay of Fundy.

.

.