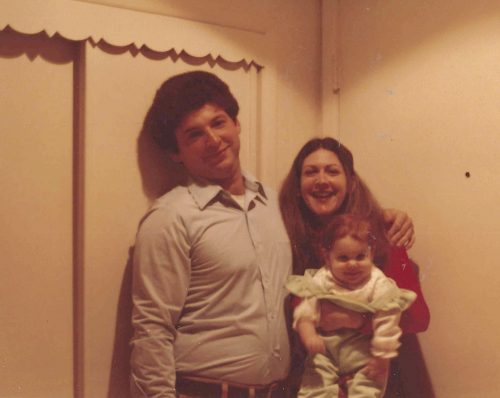

Author with parents

Author with parents

About the time when my father, Abraham Morganstern, started to lose his memory, he began to sort through the household trash on a daily basis, picking out with surprising care bent hangers, sole-less shoes, cracked mirrors, unattached buttons, and other items he deemed worthy of resuscitation. His triumphant scavenging at first irritated my mother, Hadassah Morganstern, and me when I happened to return for a visit to the ever-more-cluttered house of my childhood, but after a while we both accepted it as a permanent facet of his new personality. I suppose if you are falling away into some sort of mental darkness, you hold onto anything concrete, even if it’s broken. It may also be his instinct to broker junk into something useful, now gone awry. My father is a self-identified junkman, the son of a junkman, himself the son of a Russian shoemaker, and before that who knows–the ancestral line lost in the rough and decisive Atlantic crossing. And Abraham Morganstern, in his heyday, was the King Midas of east coast junkmen, a working-class boy who, having lost his father as a teenager and finding himself responsible for a widowed mother and two brothers, had wheeled and dealed in paper, rags, cans, and cigarettes on the docks by the Chesapeake Bay and in the printing presses and paper mills of east Baltimore, until he assembled a small fortune. How massive his fortune, I couldn’t say, as he always retained a deep-seated sense of his lower-class origins and a childlike awe of those whom he considered truly wealthy. “That’s a self-made man, right there,” he would gush about the father of one or the other of my classmates at the Bryn Mawr School for Girls, a private school loosely affiliated with the college, both having been founded in the late 1800s by M. Carey Thomas, a cross-dressing philanthropist with a passion for female education. “He’s made of money. And you know what–you couldn’t ask for a nicer guy. That’s the whole package. Me, I’m barely middle-class.” If his progeny, my sister Eloisa Isobel and me, applied themselves then, with the benefit of postgraduate education, we could ascend into the heights of upper class, and, he always added, take care of him in his old age. That old age confronted him far sooner than I had expected, as before his sixtieth birthday he commenced the torturous process of drifting away from himself. At sixty-seven, his mind seemed increasingly defenseless against the waters of Lethe, which flushed out all traits of tenderness and humor but somehow left the stubborn hell intact.

King Lear, which used to be my least favorite Shakespeare tragedy, began making sense to me after witnessing my father’s decline. He seemed to be lost perpetually in an erratic storm I couldn’t see. Sometimes he jumped back and shielded his eyes, as if in the wake of a lightening flash. And while he instantly forgot the anger that thundered through his body at unpredictable moments, it left us all awestruck at the strength still lingering in his failing body. The stress of soothing him through moods alternatively volatile and timorous became too much for my mother. She retired from her job as an English teacher to care for him but even then she needed to take breaks. During the winters she absented herself in Florida for as long as she could prevail upon my sister or me to take over as companion for him. A desire to relieve her for a bit, along with the lengthy vacations endemic to an academic career, has led me to spend increasing amounts of time with him. I spent nearly a month at home during my sabbatical, during which we fell into an unaccustomed intimacy, without the buffer of mother and sister and apart from the rhythms of work and school that had always held us in check from each other.

***

At the diner, New Years Day 2016

At the diner, New Years Day 2016

When my father, Abraham Morganstern, was fifteen, a Baltimore city bus rode over his right foot. He lost three toes, missed four months of his freshman year of high school, and was subsequently ineligible for the Vietnam draft. Being what he has always termed derisively a bleeding heart liberal, I can hardly regret that he didn’t have to suffer unendurable horrors for inexplicable reasons like many of his contemporaries and most of his high school friends, yet I’ve always thought he would have thrived in the army. He enjoys uniformity, regularity, conformity, and consistency. He is a man who possesses a deep-seated suspicion of the abstract, preferring newspapers to books, Norman Rockwell to Pablo Picasso, print to cursive, and dogs to cats. He has worn Docker slacks and Redwing loafers for forty years and only stays in Hampton Inns regardless of whether he is visiting Tuscaloosa or Paris. Alzheimer’s has only intensified the comfort he finds in the habitual. And thus, every night I stayed with him during my sabbatical, we ate dinner at The Acropolis, a twenty-four hour diner run by kind-hearted Greek emigres accustomed to my father’s habits.

Every night, we enacted the same rituals. My father introduced me to the waitresses and busboys, all congenial offshoots of the Greek diner familia, and we all acted as if it were the first time, as if we too had fallen into the minuscule eternity of a perpetual moment. “This is my daughter. She’s the professor,” he announced in delight, as we took our seats in the red leather booth next to the jukebox. The waitresses and busboys would wink at me and exclaim how smart I must be, how I looked just like my mother, and shake my hand to introduce themselves.

I always ordered for both of us. I varied my order between various breakfast foods but without fail he ate a turkey burger with onions but no lettuce and tomatoes and a side of waffle fries. Whenever the waitress brought us our drinks (Diet Coke for him, glass of slightly dreadful house red wine for me) I always watched him carefully fold up his straw wrapper with studied concentration. Only after he had placed it carefully in his back pocket would he turn to me, his face bright, shining, excited, expectant.

“Tell me what’s new!” he said to me one night at the diner. “I haven’t seen you in almost six months.” I didn’t protest although I had been home for about a week at that point.

“Well, I do have some good news, actually. I found out that I have tenure now.”

“That’s wonderful,” his smile split open his long freckled face.

“Thanks! Check out my business card.” Before leaving home I had stuffed a stack of business cards in my purse for precisely this purpose. He turned it over in admiration and asked if he could keep it. I had given him dozens over the two years since I had actually gotten tenure.

“Well, I am really proud of you. You are so smart.” He shook his head. “You must get that from your mother.” That was the wrong word at the wrong time. It triggered a reverberation of memory and betrayal. His face reddened and his voice grew thick with menace. “Where is your mother? I know she’s not here. Did she go away? Why didn’t she take me with her?”

I was afraid of him in those moments. Because I like things to be polite and calm and peaceful. Because he was still my father, and his flares of temper reminded me of the days when he and my mother had arbitrated morality, judgement, and penance, when I talked back, when I lost my retainer, when I announced I was majoring in medieval studies instead of something they deemed practical. Because his voice thundered too loud for polite conversation, and at that moment in the diner, people were starting to turn around, and I didn’t want him to reveal his weakness to a world that had always shown him deference.

“She just went off for a few days. But I’m here. And I’m here for almost a month,” I said quickly and brightly.

“Well, I didn’t know that. A whole month.” He shoulders relaxed and he opened up his copy of the Baltimore Sun. “Do you want the sports section?”

“Yeah, right.” I grimaced and held up a book on French convents I was meant to be reviewing for a tiny feminist medieval journal. I was relieved. If unchecked, his anger could flail out limitlessly. Last winter, he had chased my mother and sister into my old bedroom and punched a hole through the door. Now he wanders by the room in surprise, puzzling at the gap in the wood.

He held up his newspaper to the fluorescent lights, squinted, and then brought it close to his nose to sniff, as if he could smell the oil on the machines that pressed out the pulp and before that, the perfumes the wood had exuded at the moment of splitting. I had seen him repeat this action a thousand times over the years. Most of his business had come from buying and selling paper, and he understood and respected its shades and varieties. At my childhood birthday parties, he would carefully unfold all the wrapping paper I tossed aside in an ecstasy of anticipation and lovingly examine it like a Vatican official authenticating a sacred relic.

Despite that brief moment of calm, his body would stiffen again and again that night and each night, and I would watch his internal temperature drop or rise into anger, I was never sure which one. Anything could provoke the outbursts–the lack of industry in America today, his french fries touching his cole slaw, the price of gas. Regardless of the issue, his voice thundered like a minister denouncing Satan. I would speak in soothing tones, handing him my business card, creating word games to play on the place mats, pulling out my phone to show him pictures of my dogs, anything to coax him back into tranquility.

***

It seems to me that humans are obsessed with imposing order onto the rhythms of earth. Do we follow the pull of the moon, the cycles of the sun, calculations Julian or Gregorian? Is it a day of rest or a day of work? How do we steady ourselves upon this spinning world? Some internal clock had shattered in my father; all the calendars in the world couldn’t seem to ground him in time. He still knew who he was, and as long as he was somewhere familiar, where he was, but he could not grasp when he was and the impulse to remember left him frantic.

“What year is this? How old am I?” he asked me plaintively, on a loop, in the morning when he first awoke, during meals, during drives. If I was in the same room, I would watch him count the years on his fingers, his ring finger scarred from when it once caught on the roof of a truck he was loading with paper rolls.

“Am I sixty-six?”

“You are sixty-seven, Daddy,” I would call out, while brushing my teeth, or reading, or running the water for dishes.

He would launch into a lengthy explanation about how even though he was already eligible for social security he was planning to wait so that he could increase the amount so my mother would have more when he died. I always agreed with him although I never really listened. I probably should have paid more attention. He had always understood how to invest, how to profit, whereas I could never save a cent. But my attention always wandered, out of habit, as if he were instructing me about stocks and bonds and I was still a bored teenager nodding to keep him happy.

He was able to sustain the conversation for about five minutes before the cycle began again. In mid-sentence, suddenly, he would pause and ask what year it was, how old he was.

Why were we both stranded on different planes? I could move through the day as if through a museum, with paintings and sculptures by different artists from different ages, from golden icons to rotund Madonnas, changing from room to room. He saw each day, each cycle of a few moments, as one painting in a series of the same object, like Monet’s water lilies, going increasingly out of focus in an afternoon of lengthening shadows.

***

Author’s mother and father

Author’s mother and father

On the outside, the house my parents had moved us into when I was three years old still looks like a respectable suburban split level, but on the inside, it is decaying. The water from leaking pipes has bruised the first floor ceiling with purple water stains. A giant hole above the stairs exposes the skeleton of the house, aging and failing no less so than its inhabitants. Until sympathy for my mother’s cares had overcome my hygienic scruples, I had avoided staying at the house more than once or twice a year.

The house had always been cluttered, although generally sturdy. For years it was the repository of familial possessions from both sides. When my father’s uncle Sheldon had a heart attack at the Pimlico racetrack, his Dinah Shore records, his roll top desk, and his threadbare plaid suits infused with cigar smoke, all ended up in our living room. Esther Collector, my mother’s mother, couldn’t abide possessions, and over the years she had sent her diminutive good-humored husband to our house laden with Wedgwood sets, teak end tables, and porcelain planters, all of which had ended up in the hallway in wobbly stacks. These shabby heirlooms gathered dust side by side with sheets of bubble wrap, disembodied and translucent like antique wedding veils, cans sticky with soda, my sister’s college futon, outdated copies of the Baltimore Jewish Times in tenuous heaps. The clutter had built over the years, forming archaeological levels–Level 1 1980-1982 AD, Level II 1982-1984 [early, middle, late], each level built on the rubble of the previous years. The present level existed in some late decadent age from a civilization in decline, fraught with invasion and decay. Of course, I thought wryly, even the Germanic barbarians had maintained the Roman baths. Out of three bathrooms in the house, only one still has a flushing toilet and running water in the sink. The shower is entirely off limits. If you turn on the water, it runs through the floor into the living room below. My father and I conducted our ablutions as best as we could in the one sink, which drained poorly and bore a lingering patina of hair and soap suds. The other two bathrooms had become glorified storage closets, full of mildewed towels and empty bottles of anti-aging creams.

I had avoided coming home for years because I had found my efforts to fight the chaos continuously frustrated. It was far easier, I realized, to accept the reality–the hordes of newspapers and old litter boxes and the styrofoam cups towering unsteadily to the ceiling. With no working showers, I just gave into the grubbiness and settled in among the disarray. It was glorious, in a way, to simply become the body I already was, without fighting the daily onslaught of effluvium and odors. My pillows smelled sour from my hair, and when I sunk into the sheets at night I breathed in a nutty fragrance, as if I was stretching out on a forest floor. What did it matter, really? I drove to the library each morning and then accompanied my father to the diner each night. I moved through the grocery store and the post office anonymously. My rhythms were entirely his. I half slept at night, alert for his turnings and grumblings, his faint sleepy cries in the early morning– “Hadassah, I hurt so bad.”

I slept in my sister’s old room, since she had rendered my own uninhabitable when she moved home two years ago, moved in her kitten, and promptly moved out my old bed, ripped off my Pre-Raphaelite posters and playbills from high school triumphs from the wall, and then moved back out, leaving behind the detritus of a shopping addiction and a cat with a urinary tract infection. She was two years younger than me, a short plump brunette who had recently moved to Boston with grand promises of becoming a freelance fashion writer.

My mother kept the door to my old bedroom closed, so Capricious the cat didn’t disappear inside. I did venture in one time. The light bulbs had burned out, leaving the ridges of possessions cast in grey light through the shuttered windows. My sister had left in a hurry, as if fleeing a war zone, abandoning piles of shoes and leather purses. The dresser was stacked with towers of Starbucks cups with lipstick rims and half-filled water bottles. An acrid smell in the air indicated that she had left a full litter box under old boxes spilling over with tissue paper. Somewhere beneath all that were my old dolls and books. She had attacked the room with a certain hostility indicating she had never forgiven me for existing, for enjoying the bigger room throughout childhood, and for resembling the fair-haired slender Collectors rather than the stocky Morgansterns.

She possessed far less patience for my father now than I did, which was surprising, given that she had always been the Daddy’s girl growing up. They rode bikes together, shot baskets for hours on end, told jokes and sang song lyrics in the car. Their clamorous antics embarrassed and annoyed me. I was very much my mother’s daughter, which meant I was quiet and absorbed in my own world. My father and sister were more sociable creatures. They possessed matching unpredictable tempers and were partners in rage as well as play. I knew I loved him (I wasn’t so sure about her) but I did spend a lot of time wishing him away, willing the house into quiet and calm. “You’re too loud with her. She doesn’t like it. Can’t you see that?” I remember my mother chiding him over the years.

In return, he courted me, stilling his loud, clumsy attentions and approaching me with a kind of reverence. He presented me with small offerings of books and ideas, usually age-inappropriate, gleaned from conversations and articles and radio shows so that at six and seven I read Clan of the Cave Bear and War and Peace and a scintillating host of Jackie Collins novels. I remember one glorious yard sale where he bought me a biography of Anne Boleyn, a biography of Queen Victoria, and a battered copy of a book about girls who went to summer camp and learned how to make voodoo dolls, and after reading all of them in furious delight, I decided that I was going to become a writer, and a historian, and go to camp the next summer. He watched me fill up a series of floral-covered bound notebooks with fledgling biographies of queens and stories about girls going to summer camp, and then he brought me home a gleaming electric typewriter.

“And why does a ten-year-old need a typewriter?” my mother had demanded sharply, but fondly.

“You’ll thank me when she gets into Harvard,” he responded smugly, watching me enthusiastically hunt and peck on the shiny black keys. “She’s smart, like you.”

I didn’t get into Harvard, but like almost all graduates of the Bryn Mawr School for girls, I ended up at a reasonably rated four-year college, and my father spent a sticky August afternoon in upstate New York moving endless boxes into my fourth-floor dorm room. After a trip to Kmart to buy an area rug, a mini-fridge, the dorm-authorized sticky gum that wouldn’t leave marks on walls, and all the other forgotten extras, my mother headed to the car, exhausted, for the seven-hour drive back to Baltimore, and he stayed behind for a moment. I had been nervous and impatient all day, by turns clinging to them and encouraging them to leave. We stood looking at each other in this room newly hung with specially purchased Pre-Raphaelite posters, and surrounded by standard wooden furniture into which I had to unpack all my clothes and books and suddenly, with his eyes still fixed on me, his body sagged and slumped and finally ruptured into sobs such as I had never heard before. Spontaneously, as if mirroring him, I cried furiously, hot with resentment at this assault on my shaky confidence in my new life. After a few moments, he gasped in a way that was almost a wail, and then turned on his heel and stumbled out of the room, and I didn’t see him again until Thanksgiving.

***

Every night, blue light flashed from the TV down the hall, and I fell asleep listening to the spluttering and popping of gunshots. My father watched old cowboy movies late into the night. He found comfort in the familiar plots and the simplistic binaries of good and evil without any moral ambiguity. In between the shrieks and the shots I could hear him murmur to the cat, “You’re my favorite daughter. I hope you know that.”

One night after I had been home for about a week, as I rolled up in an old bathrobe and a crocheted coverlet, drifting off to sleep, I heard his bed creak. The floor groaned as he made his way to Eloisa Isobel’s old room. He lingered in the doorway, his tall body drooping, his face growing so long and thin it seemed to disappear into the hollows of his throat.

“What’s going on, Daddy?” I murmured, sleepy, but alert.

“What do you think of that cat? She’s really something, isn’t she?”

I agreed with him, somewhat irritably. No one would believe it, but he had never even liked cats until a few years ago. My sister and I had begged him for a pet for most of our childhoods, to no avail. Now Capricious had become the one creature to whom he was always kind, to whom he always spoke softly. He stood in the doorway and kept talking while I wished he would go away so I could fall asleep. When I think about these moments, I wish I could have been more patient, the way he must have been with me when I was a baby and interrupted his sleep with my nonsensical noises.

He came and sat on the bed and groaned. “I’m falling apart,” he proclaimed. He wore a frayed yellowing undershirt and underpants full of holes that hung off his hips, heedless of modesty. I wondered at this frail failing body, and I thought how impossibly strange it was that he had once been a young man, that this body had once conceived two children in desire and raised them up in hope. This whole thing baffled me—the way the image that sprung into my mind when I summoned the word “Father” had shifted over the years from a red-headed giant who could repair, lift, or solve anything with which the world confronted him to a shadowy being who I needed to protect from that same world.

***

There is one picture of my father and I taken when I was about five, that remains my favorite. It’s a close-up of the two of us, his arm is around my waist. I’m in a blue checked dress with a white lace collar. My hair was lighter and his was darker, so we both have matching copper curls. His face is unlined, heavier, his smile is so wide it practically splits open the picture. I remember that day in diffused dreamlike scenes. He had taken me to a house where there were girls my own age. I think they were the daughters of his college friends visiting from out of town. I was supposed to be playing with them, and for some unknown reason, a sense of dread palpable even today, I refused to leave his side. I clung to him all day long, despite his attempts to nudge me in the direction of the other girls. It may have been a dream I imagined to explain the picture. But what I remember is this desire for him to shield me from the unknown. Somehow he had become the unknown, with his quicksilver moods and his storms of anger. That father to whom I had clung with such adoration was gone already, lost to the shadows that pulled him further into another world. It was as if he was stuck between those two planes of existence, and the result was mental and physical chaos. What I couldn’t decide was whether I still wanted to cling a little bit longer, how quickly I hoped he would disappear entirely into wherever he was meant to go.

—Laura Michele Diener

Laura Michele Diener teaches medieval history and women’s studies at Marshall University in Huntington, West Virginia. She received her PhD in history from The Ohio State University and has studied at Vassar College, Newnham College, Cambridge, and most recently, Vermont College of Fine Arts. Her creative writing has appeared in The Catholic Worker, Lake Effect, Appalachian Heritage,and Cargo Literary Magazine, and she is a regular contributor to Yes! Magazine.