March is coming, the new issue, the Exotic/Quixotic issue, the overflowing cup issue!

Striking a blow for freedom of expression and the protean nature of art, we like to publish things that don’t fit in conventional slots, especially those academic creative writing niche slots like the personal essay (you know, where you write about something interesting but bring in your relationship with your boyfriend as well). We love the aphorism, the short nonfiction form. We publish aphorisms and extended aphorisms and essays that are formally long aphorisms. We also publish memoir and place pieces and book reviews that bring in craft and structure. In the latter, I am firmly convinced, you express yourself in the choices you make (without having to mention, um, yourself or your boyfriend).

One of the highlights of this issue is the excerpt from Joël Gayraud’s The Shadow’s Skin, translated from the French by S. D. Chrostowska (whose own incendiary book of extended aphorisms MATCHES: A Light Book we excerpted in our December issue). Books like these owe much to the example of Nietzsche who wrote in fragments or mini-essays or thought experiments or, perhaps, Adorno’s Minima Moralia, one of my all time favourites.

It’s also worth noting that in this issue we have a veritable plethora (you have to get the word “plethora” in every six months or so) of book reviews. This is a consequence of our policy of (like the airlines) double booking reviews, which have a way of not coming in on time or disappearing entirely (this has more to do with the vagaries of publishing schedules and the mail than our tribe of reviewers, a punctual and hardworking group). But then every once in a while a whole bunch of reviews arrive at once and suddenly the double booked flight is, well, double booked.

So this is a huge issue!

The development of sadomasochistic practices contributes more effectively than many revolutionary discourses to undermining the psychological foundations of power. When, in the intimacy of their bedroom, couples experimented with the game of submission and dominance—even where the sexual roles themselves remain uncriticized, the mere fact that this game took place enables the objectification of old fantasies of domination and slavery—fantasies that, as a consequence of the brutal and barbaric establishment of relations of domination, have been buried deep in the breast of humanity. — Joël Gayraud

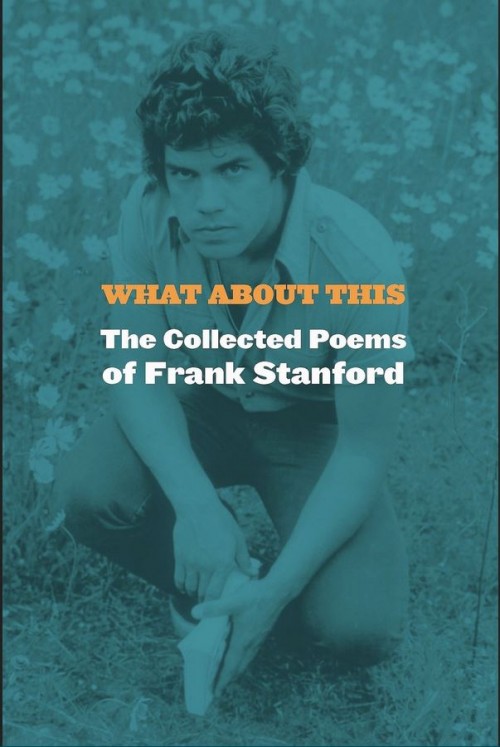

Allan Cooper reviews What About This, The Collected Poems of Frank Stanford. Stanford was a great, undersung, Mississippi-born cult poet, one of those divine eccentrics. The book has been named a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award in Poetry, winner to be announced March 17.

If we’re lucky, once or twice in a generation an artist comes along who changes the complexion of our entire landscape and gives us a way of seeing the world as we have never experienced it before. Often these artists receive little or no recognition in their lifetimes, and it takes years–sometimes generations–for their genius to be acknowledged. I think of the work of William Blake and John Clare, Emily Dickinson, Vincent van Gogh, Paula Modersohn-Becker and the haunting, other-worldly poems of Frank Stanford. —Allan Cooper

New to the magazine, Carolyn Ogburn answered one of my want-ads for a music writer. This is her first contribution, an interview with the North Carolina musician/composer Ivan Seng. The title of the piece is “a random walk,” but you need to know what a random walk is. See below where Ivan Seng explains.

Well, random walk is a mathematical term. It comes from Brownian motion. Do you remember the story of the guy [botanist Robert Brown] who was looking though his microscope at tiny particles in water. He saw these particles and he saw them bouncing around – he saw that these particles were following this completely random motion, Brownian motion – and I think it’s how they realized that there were atoms, because it ended up being that these atoms were bouncing off of these small little particles and it was pushing the particles around… So if we took a very basic motion… say you have a 3-sided die, marked 0-1-2, and each number correlates to a particular movement. And [your particle, or sound, in its own placement is affected by the dictates of the die] and you start at a certain number, 0, and you can go up a step or down a step. But it’s unpredictable. —Ivan Seng

We also have a fist full of poems from Kenneth E. Harrison, Jr., delicate, lambent, melancholy.

A morning difficult to walk across

the slain crocuses a song

or a silent movie

a memory of a wound

floated out to sea

at the beginning of the war

the fields covered by searchlights

at the edge of a garden before we were born

—Kenneth E. Harrison

Mark Sampson reviews the wild and wooly collection of fragments/stories Bret Easton Ellis and the Other Dogs by the Swedish writer Lina Wolff.

Wolff’s project – a text at once fragmented enough to pass for a short story collection and yet untraceably centred on the character of Alba Cambó, a writer of violent, horrifying tales who has been diagnosed with terminal cancer – draws a connection between the canine-like nature of human males and the limitations of revenge against their more animalistic natures by women. — Mark Sampson

Natalia Sarkissian reviews Party Headquarters by the Bulgarian novelist Georgi Tenev.

In Party Headquarters Georgi Tenev reduces the traditional novel with its linear time, clear relationships, memory and complex characters to an indissoluble essence. Characters, for example, are nameless—they are merely bodies or even types. Memory, hallucination and current narrative merge creating a fluid world where time is relative. —Natalia Sarkissian

We have this month inspired, comic, eccentric, Monty Python-esque fiction from the Irish writer Alan Cunningham.

Idea for a script, no, play.

No, idea for a novel.

•

A man – no, woman – too many men in literature, opens a suitcase in a living room of a building apartment, starts to place all these, like, well, all these different objects into it. Not sure what they could be – yet. She puts all these – well, things – she puts all these things into the suitcase, leaves her apartment in a city – let’s say, London – and starts walking. —Alan Cunningham

The English novelist turns his hand to short story analysis and structure, beginning his exploration with Alice Munro’s short story “Jakarta,” using a device called the Greimas Semiotic Square to parse a set of relationships he finds crucial to the short story.

All these magnificent stories are highly organised, intense studies of humans interacting and behaving oddly with each other. They throw light on sublimated desires and warped motives. Ultimately, however, in all of these stories, it is some kind of lack, absence or failure of one corner of the square that triggers catastrophic change and collapse in the other three. There must be a black hole, a sacrificial lamb, for the story to work and it is these black holes that are the secret keys to the stories. Through them, we slip down a wormhole and emerge at the story’s end with fresh understanding of just how weird and wonderful human beings can be. —Richard Skinner

Julian Hanna contributes an offbeat What It’s Like Living Here piece, Julian walking in Madeira where he lives, a tale of a complicated beauty, of a place both difficult and enticing.

If I dig deep, I think it’s that I love the contrast – between the breathtaking beauty, the tropical flowers and sun and sea on one hand; and the plague of traffic and stupidity and all kinds of human failings, which are universal failings, on the other. Anyone who has travelled in southern European cities like Athens or Barcelona or Naples, not to mention the cities of the global south, knows this contrast and its peculiar frisson. Something about the ugliness and beauty of human life, the union of pain and pleasure, is ultimately why I live here and why I walk. I like things to be difficult. —Julian Hanna

Karen Mulhallen returns to the magazine with a handful of love poems, mad love, foolish love — is there any other kind?

It can’t be helped

I wasn’t ready, or maybe I was really ready

ready for love

had no defenses

wasn’t prepared

just jumped in

and now

the undertow is

taking me down.

—Karen Mulhallen

Richard Farrell continues to mine the stories of his past, especially his years as a prospective U. S. Navy pilot — this time a sublime and sublimely sad essay about a classmate, a plebe, who committed suicide at the Academy.

Ten years after the Worcester Air Show, still pursuing my dream of becoming a Navy pilot, I returned from physics lab to my room at the United States Naval Academy, only to find that a plebe from 10th Company had climbed out of his fifth-floor window and plunged to the brick walkway below.

His shattered, uniformed body was visible from my window as paramedics rushed in vain to save his life. Ambulances, fire trucks, and police cars had cordoned off the road, but the air was eerily still. I expected sirens, but heard only the chirping of birds, the rustle of a breeze off the Chesapeake. Again, it was September. A warm, clear day sparkled. Spinnakers billowed on the Severn River as sailboats tacked their way out to the hazy bay. —Richard Farrell

Frank Richardson reviews a book he loves, Jenny Erpenbeck’s The End of Days.

The End of Days, a book of elegant style and penetrating insight, filled with arresting characters and provocative questions, is a book to come back to a second time, and a third, and . . . who knows how many times? Erpenbeck writes with a gentle intensity—a feeling light as a dream yet so grounded in the moment that if a grenade exploded outside your window, you wouldn’t jump. Although death frames the novel, The End of Days celebrates the beginning of days, for it affirms life’s multiplicity and the potential of every human life. Erpenbeck quotes W. G. Sebald’s Austerlitz in an epigraph; in part, he asks—“where will we be going now?” This question vibrates throughout her novel and remains with us as we move on from this book, and this life, to the next. — Frank Richardson

Jeff Bursey sums up the life & works of the great Sam Savage.

Sam Savage has a genius for getting inside his characters’ heads and bringing out their worst and best traits in such a way that we are never in doubt that the individual—it can be man or woman or, yes, animal—is a presence who has felt pain and sorrow and has a story to tell. His lead characters are intensely believable because the language is intense and believable. This exquisite combination of words and psychology, along with Savage’s knowing penchant for idiosyncratic behaviour, is rare indeed, not found in fiction as frequently as we might desire. —Jeff Bursey

Jeff Bursey, who appears twice, yes, in this issue, reviews the novel A General Theory of Oblivion by history-obsessed, Angolan-Portuguese author José Eduardo Agualusa.

…strong women, women praised for their beauty, ignorant men, thick-headed and greedy men, victims of tragedy, and the kind-hearted. Above them all is Ludovica (Ludo) who has accompanied her sister, Odete, and her new brother-in-law, Orlando, from Portugal to Angola just before independence is brought about. She is the figure Agualusa focuses on. Through her, despite her isolation in an apartment building, we are given an overview of Angolan history and society. —Jeff Bursey

Roger Weingarten, Self Portrait through a Keyhole

Roger Weingarten, Self Portrait through a Keyhole

And there is, as I always say, MORE! Including art work from the poet Roger Weingarten, excerpts from the anthology DIRT: A Love Story, a new NC at the Movies, and new work from Ireland.