.

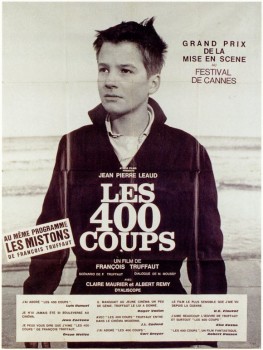

An almost lethal dose of high school anxiety, peer pressure, and girl gangs courses through the veins of Sofia Coppola’s second short film “Lick the Star.” Coppola, best know for films like Lost in Translation, Somewhere, and The Virgin Suicides, throws us into a terrifying world called the seventh grade via a protagonist with a broken foot (her father ran over it by mistake and she’s been out of school for a few days). Our wounded protagonist arrives at school via car, in an opening driving shot reminiscent of the French New Wave’s Francois Truffaut’s 400 Blows, with the streets of Paris replaced here by suburban driveways.

Seventh grade is a feral fighting pit where the young women are on the brink of enacting a plan to poison the boys in the school inspired by the book they love, V. C. Andrews’s Flowers in the Attic. As the protagonist / narrator notes, a lot can happen in a week (“Missing school is like a death wish”) and she’s arrived back to the fighting pit with a broken foot. It does not look good for her, and vicariously us, the wounded gazelle(s) on the edge of the herd.

In one of the more endearing moments in the film, the teen girls study the boys, what the boys eat, attempt to learn the numbers to their combination locks. All ostensibly to poison them, but there is something about the boys that intrigues them, so they seem undecided about which one to poison first. Indeed, their intent may not be to murder, but just to slow the boys down a little, assert an ounce of control in this volatile and unpredictable high school world.

There’s something here too that subverts typical gender constructions of young women, repressive constructions to be sure, so that when young women do rebel in films or act out they become a site of horror or something to be feared: Ginger Snaps, Heavenly Creatures, Pretty Little Liars. So much for the sugar and space and everything nice; Chloe and her rat poison have other plans.

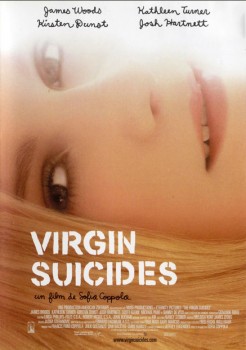

The girls’ anthropological stakeout anticipates Coppola’s later film The Virgin Suicides in which the boys are the ones fascinated with the five mysterious Lisbon sisters. Both films construct the other gender as an unknowable, unpredictable and almost threatening place just out of reach. A longed for, unapproachable truth.

In “Lick the Star,” the young women seem equally perplexed with their own gender, in awe and fear of the antagonist, rat-poison wielding queen bee of the seventh grade, Chloe. She is the one girls give up their seats for, shoplift for and play minion to. Sparkly eyelids, a noir-lipsticked assassin’s smirk and ironically coy ponytails all caught in slow motion as she arrives at the school, her kingdom.

Even in this early film, Coppola’s sense of style finds flourishes. As Anna Rogers notes about Coppola in Senses of Cinema, her mise-en-scene “creates an affecting and primarily visual style, often at the expense of extended dialogue, this same style also serves to cover, but only partially so, the spectre of something dark and insidious.’

Stylistically the film resembles Truffaut’s 400 Blows in other ways too: the film is shot in black and white and the classroom shots recall its school shots. There, however, teachers and adults of all sorts provide the tyranny to revolt against. Here, the other seventh graders are the ones to fear. Thematically, too, the film has an anti-establishment air and flirts with the criminal impulse (they steal the rat poison, they break into the boys’ lockers and they plan to poison them and they smoke behind the bleachers, a crime so great that when our protagonist is caught the principal changes her status to “non student.”

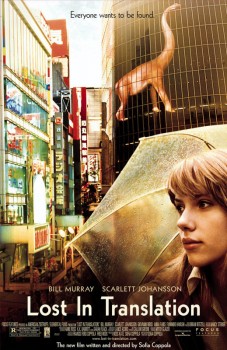

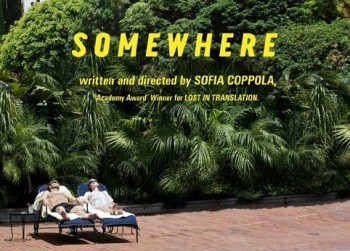

What unfolds for Chloe and our one-footed protagonist suggests power and popularity are fickle and flux. Ultimately this plays out as the tension between the desire to belong and the fear of becoming an individual, isolated. This anticipates Coppola’s later explorations of isolation, in Tokyo hotel rooms and beside Hollywood pools. Yet after this short, all that adult ennui looks like kids play next to having to eat lunch alone in seventh grade.

— R. W. Gray

.

.

Hello! Have you by any chance seen the film “Mi Vida Loca” by Allison Anders? It has now become almost a time capsule of early 1990’s/pre-hipster Echo Park in East LA.

While Anders’ sensibility is quite different, it shares with Coppola’s a sensitivity to the young women it portrays, and pulsates with rich, Gothic murals and gang graffiti (East LA via Sevilla, Spain). Highly recommended!