.

I have three bookcases full of poetry books in my house, one whole bookcase taken up with hefty anthologies like The Oxford Book of American Poetry, along with classics (thank you, Homer, Chaucer, Blake, Hopkins, Dickinson, Whitman) and Collected Works (thank you Auden, Moore, Brodsky, Merrill, Heaney) and books about the craft of writing. The other two cases, however – a total of twelve shelves, 30″ each shelf – are filled with individual “slim volumes” by poets with a few books out and with, often, long teaching careers and honorable but minor reputations.

A remarkable number of 1/4″ spines can fit into 360 inches, especially when they’re mostly paperbacks, as mine are. There are a handful of poets whose early hardcover books I’ve lusted after and, bit by bit, collected (thank you, Anthony Hecht, John Hollander, Richard Wilbur) and another bundle of hardcover books written by professors and mentors whose work I love (thank you Richard Kenney, Heather McHugh, Linda Bierds.) I have a nice stack of books by friends (thank you Walker, Wing, Hoogs, Whitmarsh, Cornish, Arthur) and I have my own poetry books for children plus copies of reviews that my adult work has appeared in.

The remaining space is filled with books by poets who have won some fine contests, gotten published, gotten some buzz, earned teaching positions, generated enough excitement to establish a loyal (usually regional) cadre of followers, but never really become “major” poets. Each one of those books has elegant, finely crafted poems in it, poems which are idiosyncratic in the best way, that is, with an identifiable, strong voice. Just as most books by well-known poets can be uneven, these books by lesser known poets can be uneven; that’s as true for the reading of an individual book by Auden as it is for any one of these many “slim volume” poets. There are poems I pass by after one reading, but there are also poems that reach out and grab me by the collar and shake me to my bones. There are poems I share with friends – a grassroots effort that mimics my approach to politics: support who and what you love. Buy their books. Talk them up. Cross fingers.

I wonder sometimes whether, if submitted to a blind “taste test,” some of the best poems that stay quietly within the covers of these slim volumes might not be mistaken for the writing of poets with much heftier reputations. And, as usual with this series about “undersung” poets, I wonder about the whys and wherefores of “success” in general. Did (or do) these poets long to be well-known, or were they satisfied professionally? Did they dedicate themselves to mentoring and thus forget (or express contempt for) the process of self-promotion? Did they battle with good-old-boy systems? Did they know the right people, and – if they did – did they use the right people in order to get ahead? Did they quit poetry and move on to anything less disappointing or better paying or fresher or simply different or…? Did they suffer poetry fatigue? Were they simply in the right place at the wrong time, wrong place at the right time? Did their gender or ethnicity present stumbling blocks? Were they shy? Were they, ultimately, satisfied by poetry, or would they rather have been fishing, playing the trombone, painting? Was publication enough? Did they – or do they, for those who are still alive – want more? “Success” – is it really counted sweetest by those whom it bypasses? Does it really interrupt that “sorest need” which Dickinson said was required in order to “comprehend a nectar”?

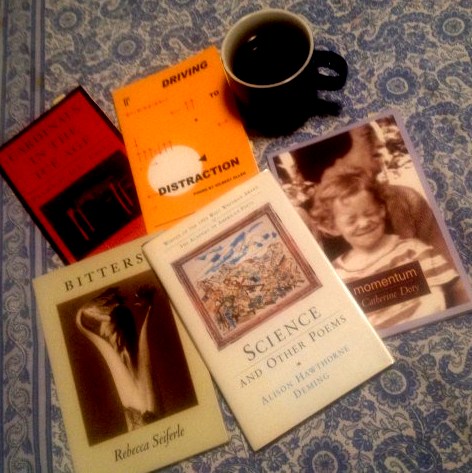

Here are five poems, one from each of five separate books I pulled randomly off my shelves. I’ve purposely left out biographical details about the five poets, though you can easily click on their names to get further information about them. Some were winners of the National Poetry Series competition or the Walt Whitman Award, several earned fellowships like the Guggenheim, one was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize, most earned residencies at respected workshops and retreats, as well as State Arts Commission awards. Some are still publishing and can expect their reputations to continue developing. But for reasons that continue to elude me – and, of course, the reasons are multiple rather than simple – the names of these poets are relatively unfamiliar to most poetry readers.

Yet I think these five poems measure up to most of the contemporary poems in the Oxford Book of American Poetry – they are precise, original, layered, large, and full of leaps that take the breath away. They use language beautifully and, though not formal in terms of rhyme or meter, they are “musical” – like the best musical compositions, they care about the sound they make, and like the best humor, they increase in appeal when spoken aloud with just the right emphasis. In what way do the poems in well-recognized anthologies surpass these five? I haven’t figured it out. Can it be as simple as personal taste – is that what the best anthologists do, insist on including what they like? If so, are we unduly influenced, are we struggling to “like” work we don’t actually like (and what is that thick volume of John Ashbery’s Collected Poems doing on my shelf if his work doesn’t appeal to me; is it there because J.D. McClatchy likes it? Because Harold Bloom likes it, David Lehman likes it?) “Success” – is it counted sweetest, Emily, by those who go all out trying to achieve it? I’m curious to see what the readers of Numéro Cinq think.

—Julie Larios

.

Sunrise

Throughout the night the sky

had been wild with stars.

Then in the morning came an instant

when the hills sharpened, and grew shadowless,

and the world seemed no casual

enterprise of creation. From beyond the hills

rose the soft pillars of light,

until, as if caught by high winds,

they wove and interwove, and became

the bright, close fabric of sky.

Later came a burst of warm rain,

but by sunset the light had cleared,

and at the tip of one needle of the white pine

that shaded the front porch, a drop of rainwater

trembled. It was clear

as ice. It contained a fierce,

quivering image of the sun.

The light drew back, and back,

and with no further evidence of breath

the sky was precisely as it had ever been.

—John Engels (from Cardinals in the Ice Age (Graywolf Press, 1987)

.

Language with Pony Track

You’d think the rich stink of pony

would rule the senses, but violets, sunflowers,

hollyhocks draw the eyes which dart

from the shaggy Shetland’s horrible privates,

a-drop and a-swing like the backstage works

of St. Ag’s, to a bank of tiger lilies, those carroty stars.

Two girls, the sides of their sneakers

worn away, wearing tattoos of water paint

rubbed on with spit, check it out:

the heaven of leather, fried onions, and music,

five houses from where, with no eyes for flowers

or horseflesh, their father’s face reaches

the texture and twitch of skinned hare.

—Catherine Doty, from Momentum (CavanKerry Press, 2004)

—————————–

Saint John of the Cross

He is not here in Fontiveros, Spanish Nebraska

of his birth. The red brick granary fills

with nothing but wheat, and the empty plaza

has forgotten the name of Juan de Yepes,

grandson of Jews, though it contains a statue

of his alter ego, Saint John of the Cross.

Even bound by the thinnest of golden threads,

the soul’s inexplicably bound. Leashed

in the cell, the whips of the holy friars

scourged him as he knelt, three times a week,

at dinner hour, nothing to eat but cruelty.

When he finally saw Christ, He was

falling toward him, His arms stretched back,

coming out of their sockets for love of him.

It’s clear why he left Fontiveros —

his love for mountains conceived by this

dreary view — but no one knows how he escaped

from prison. Or why love finally drove

him back. Sick, he asked to be treated

in Ubeda, for he knew no one would cure him,

the bishop would curse him: he could die

inferior, die unknown, die suffering greatly.

Only love can heal us, opening our hands

to a darkness that we keep trying to let go…

How happy he was, always leaping free of the cell —

Fontiveros, Salamanca, Ubeda, the World —

singing softly, no longer having to tear out

the feathers that kept sprouting from his limbs.

—Rebecca Seiferle from Bitters (Copper Canyon Press, 2001)

————————————-

Refuge

Glossy ibis, says the guide setting her tripod

on pavement, training the lens for the birdwatchers

to fix the downward curved bill and spindly legs

of the wader. I can’t help but itch

to get closer than this tailored birdwalk. Once

I rode to low marshland with a friend. The horses

mucking up to their knees, parting the brushy alders

where there wasn’t any trail. We gave them their heads,

trusting their instincts to get to dry land.

On the far side we rested, the woods

glowing with rust and lemon. We sat. Reins dropped,

the horses leaned to fidget the leaves.

Wind thickened in the evergreens. Then the quiet cracked —

wings that loud slapped the air — brittle legs

arrowed through weeds to land not five feet away.

The great blue heron, eye fired toward shore,

where we held our breath. Even when

we began to speak, edging slightly closer,

she stayed. And something in her lack of fear,

the fix of one black iris on us — horses,

woman and man alike, kept us in our place.

—Alison Hawthorne Deming from Science and Other Poems (LSU Press, 1994)

———————————

The Arbitrary Angel

It’s born in that sudden

spark between things: a yolking

of oxen and egg, the music

of shells and high seas.

And so it rises, of course

capriciously, a sexless

Venus from a salty meringue

masticating your good mind

until you’re determined

to do it justice — even as

the microwave sounds

like a garbage truck in reverse,

the pencil a small animal

filled with lead but still

running, running, running

everything down.

—Gilbert Allen, from Driving to Distraction (Orchises Press, 2003.)

.

.

Beautiful choice of poems, and very thoughtful observations and questions concerning the vast population of us “mid-career” poets. Julie has her finger on the pulse of our somewhat stalemated situation. But the answer to some of those questions is that we are enlivened by the process itself. I think most of the poets still write, and find deeper reasons to do so despite the elusiveness of significant recognition.

“…we are enlivened by the process of it.” Yes, I agree completely. There’s a level of satisfaction completely internal, strong, irresistible, sometimes thrilling (just the getting-it-right, the saying what we mean to say.) Thanks, Leslie, for emphasizing it.

Bless you, Julie. I don’t think any of us or any of the anthologists know whether we are any good in our own lifetimes, which is, for me, rather a liberation. That recognition of possible and even, most likely, probable and perpetual NON-recognition allows me, anyhow, to write with an eye to the work’s ambition rather than to its promotion. I am, by the way, especially pleased that you picked one of my late friend John Engels’s many lapidary poems to cite. John was so much better than his reputation suggested; he should at the very least have preceded me as one of Vermont’s poets laureate.

Sydney, it was a real stroke of luck to have pulled John’s book off the shelf – I found many poems that I could have shared with readers of this series. He was a wonderful poet.

I like your saying “the work’s ambition” – it’s a clear reminder that we are often in service to the poem itself as we write – that is, poems can want something from us, can’t they? I do wonder sometimes about the possibility of Time being an equalizer of reputations (cream rising, eventually) but I must be a pessimist. Nearly all my questions about “Why this one rather than that one?” come from my conviction (suspicion?) that great poets and their work can simply disappear for the most arbitrary or banal of reasons. It’s comforting to hear you say that the prospect of non-recognition (at least, while we’re alive and kicking…and writing) can be liberating. Hooray to that.