Houellebecq layers ambiguity with verisimilitude to create a beguilingly credible story that engenders as many questions as answers. Here is a brave new world, not of the distant future, of clones and docile populations controlled by pharmaceuticals, but one which may lurk no further away than tomorrow’s headlines. —Frank Richardson

Submission

Michel Houellebecq

Translated by Lorin Stein

Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2015

Hardback $25.00, 256 pages

ISBN: 978-0374271572

.

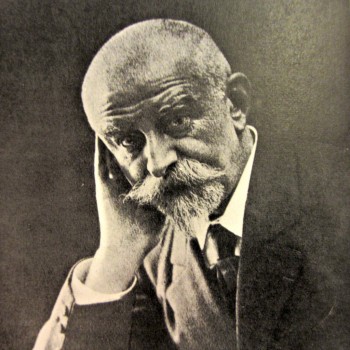

Michel Houellebecq is the bestselling, prize-winning author of novels, books of non-fiction, and numerous essays and works of poetry. His novels include Whatever, Platform, The Elementary Particles (winner of the 2002 International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award), The Possibility of an Island, and The Map and the Territory, for which he won the 2010 Prix Goncourt. Submission, his sixth novel, translated from the French by Lorin Stein, will be available in October from Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Books edited by Mr. Stein, the editor in chief for The Paris Review, have received the Pulitzer Prize, the National Book Award, and the National Book Critics Circle Award; in 2013 he was nominated for the Best Translated Book Award for his translation of Edouard Levé’s Autoportrait.

Houellebecq, now fifty-nine and living in France, has been called a provocateur, prophet, misogynist, reactionary, racist, and genius. Each of his novels arrives with its own storm of controversy, and each time we hear the stories and the labels. It was the same for Submission. On the release date, January 7th of this year, two Muslim gunmen shot and killed twelve people in the offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo; among the victims, Houellebecq’s friend, economist Bernard Mari. Ironically, that day’s issue of Charlie Hebdo featured a caricature of Houellebecq stating he would celebrate Ramadan in 2022—an allusion to the date in which his new fiction is set, a story about the ascendency of a Muslim political party. Contrary to what may have been assumed, the novel postulates a peaceful, democratically elected Muslim party which brings economic and social stability to a future France.

Submission shares many of the elements Houellebecq’s fiction is famous for, including depressed protagonists with dysfunctional lives, utopian societies, religion, and sex. François, the protagonist, examines his life during the course of a political upheaval in France, and his search for belonging, for love, and for spiritual fulfillment parallels France’s search for a new national identity. The question is, will either find what they are looking for? Can Islam provide the spiritual and philosophical needs to support a stable France, a state failed by laicism and liberal individualism? Is conversion to Islam the right choice for François? These are the surface questions the novel proposes. Houellebecq layers ambiguity with verisimilitude to create a beguilingly credible story that engenders as many questions as answers. Here is a brave new world, not of the distant future, of clones and docile populations controlled by pharmaceuticals, but one which may lurk no further away than tomorrow’s headlines.

.

Against the Grain

The novel opens with François, the protagonist and narrator, speaking to us from some point in his future. He tells us: “only literature can put you in touch with another human spirit, as a whole, with all its weaknesses and grandeurs, its limitations, its pettinesses, its obsessions, its beliefs; with whatever it finds moving, interesting, exciting, or repugnant” (6-7). Houellebecq then proceeds, in this 250-page novel to do just that, put us in touch with a human spirit.

The story takes place during a pivotal year in François’s life, beginning in April 2022, in which France, its economy falling apart, is facing a general election unlike any in its history: a Muslim political party is expected to win. François’s tone is jaded, disillusioned; he suspects the best part of his life is past. He describes himself as an atheist who is as political as a “bath towel” and “almost completely lacking in spiritual fiber.” He lives alone in a dreary apartment in the heart of Paris’s Chinatown, surviving on frozen dinners, alcohol, and cigarettes.

For fifteen years François has been teaching undergraduate courses in nineteenth century literature at the Sorbonne, and the forty-three-year-old has no ethical qualms about dating students twenty years younger than him. Despite disdaining marriage (which he reserves for those in “physical decline”) and contemporary sexual mores, the only thing François values, besides literature, is sex. His life is vacant, and the only desire he has, even if he never states it explicitly, is happiness, and the only happiness he can conceive of, sadly, is sexual gratification—well, if he’s honest, this could be improved on if the woman were also a good cook. Nevertheless, François does aspire to more in his life, as we discover whenever his meditations segue into reflections on nineteenth-century novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans.

Given that many of Houellebecq’s characters are lonely isolationists, it is not surprising that he made François a scholar of J. K. Huysmans. Like Huysmans’s protagonist in À rebours (Against the Grain or Against Nature), François is estranged from society, his job, his family, and his own love life. François’s life also parallels that of Huysmans’s—Huysmans, who struggled with his faith in God and who after much agonizing, took monastic vows; Huysmans, who found the grace Houellebecq feels denied, and thus denies François. François considers Huysmans his only friend, and his reflections on Huysmans’s spiritual journey and return to Catholicism comprise a subplot that lies at the heart of Submission. Indeed, this is one of the novel’s greatest strengths, showing us how a character as apathetic and anhedonic as François can still rise above pessimism and reach for something more spiritually rewarding than the material world and pleasures of the flesh.

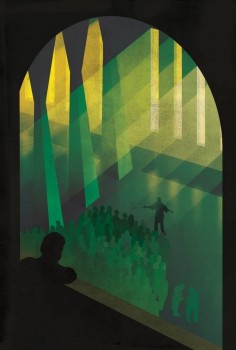

Arthur Zaidenberg illustration from Against the Grain

Arthur Zaidenberg illustration from Against the Grain

Politics

The parallel plot of Submission, the ascendency of a Muslim political party to the French government is the novel’s central conceit. In the general election, the Muslim Brotherhood (a fictional political party), led by the charismatic Mohammed Ben Abbes, comes in second behind the National Front. But in France’s multiparty system, this doesn’t mean defeat, it only means they need to make the right alliances. Ben Abbes is characterized as a political genius, a benevolent Napoleon who knows how to cater to the populace in everything from choosing a running mate to grasping that “elections would no longer be about the economy, but about values” (123). Houellebecq opposes real politicians and parties with fictional counterparts seamlessly.

After the general election, the Muslim Brotherhood forms an alliance with the Socialists to prevent the National Front from winning the presidential runoff. François watches the process on television, mostly with indifference, but when the university closes and riots break out in Paris, he packs up his car and heads south.

François spends a month in the town of Rocamadour where he visits the Chapel of Our Lady every day. While contemplating the famous Black Madonna, he thinks about Huysmans’s conversion, and he seems to have moments of sincere spiritual awakening. He speaks of the famous statue with a tone of respect, if not reverence:

This was not the baby Jesus; this was already the king of the world. His serenity and the impression he gave of spiritual power—of intangible energy—were almost terrifying. . . . What this severe statue expressed was not attachment to a homeland, to a country; not some celebration of the soldier’s manly courage; not even a child’s desire for his mother. It was something mysterious, priestly, and royal…. (134, 137)

Finally, though, he discounts his experience, blaming hypoglycemia, and when he departs for Paris he feels “fully deserted by the Spirit, reduced to my damaged, perishable body” (137). This passage parallels what Huysmans wrote in En route; from the epigraph Houellebecq chose for Submission:

I am haunted by Catholicism, intoxicated by its atmosphere of incense and wax. I hover on its outskirts, moved to tears by its prayers, touched to the very marrow by its psalms and chants. . . . And yet . . . as soon as I leave [the chapel] I become unmoved and dry. (3)

Houellebecq will give Huysmans’s emotion to François; he too will feel his heart “hardened and smoked dry by dissipation”; he too will feel “good for nothing.”

.

Brave New World

Meanwhile, under Ben Abbes’s new government crime and unemployment rates plummet, families are subsidized (so long as women stay at home with the children), and secondary and higher education are one hundred percent privatized (funded by the vast wealth of the “petromonarchs”). Abbes institutes economic policies designed to favor family-centric small businesses. He has seen the future and it is in demographics. The argument is straightforward: liberal individualism, having rejected the family as the ultimate social structure, is doomed to extinction by a low birthrate. French society is being reconfigured according to a utopian philosophy based on family (and future voters). This vision of the future isn’t as exotic as one built on clones or a pharmaceutically controlled populace, no, the future Houellebecq postulates is much more believable than the one Huxley depicted in Brave New World. And that is one sign of effective satire: the unthinkable becomes credible.

Finn Dean, Folio edition of Brave New World

Finn Dean, Folio edition of Brave New World

When François returns to Paris, women are wearing loose-fitting smocks that no longer expose their legs, his local market no longer has a kosher section, and the university is now the Islamic University of Paris-Sorbonne. François discovers he has been fired, but with the golden parachute of a full pension. His colleague Steve, who has converted to Islam per the school’s new policy, now receives three times a full pension salary along with a subsidized, “attractive” apartment; furthermore, he is pursuing his second wife under the new polygamy statutes. Consistently inconsistent, François is excited by the prospect of multiple wives.

Ben Abbes continues building his empire, drawing into the EU Algeria, Tunisia, and Morocco (with more planned). Although Houellebecq’s exposition detailing the political evolution of Europe and France is so pitch-perfect you might think you were reading about current events, one missing element is any voice of dissent. For example, no one seems to have a problem with how women’s roles are defined. The two strongest women characters, Marie-François and Myriam, barely comment.

.

The Choice

When a second pilgrimage fails, this time to Ligugé Abbey where his hero Huysmans took monastic vows, François is approached and offered the prestigious job of editing a Pléiade edition of Huysmans’s work. Although the offer is genuine, it is also a ploy to arrange a meeting between François and the politically savvy new president of the university, Robert Rediger.

François’s encounter with Rediger will prove pivotal and begins with his meeting the forty-something Rediger’s new fifteen-year-old wife in the foyer. Rediger’s first wife—“a plump woman, perhaps forty years old”—will serve them canapés and an “excellent Meursault” (a wonderful pun on Camus’s famous antihero). From the first, Rediger is described by his smile: “a lovely smile, very open, almost childlike, and extremely disarming,” a “luminous, innocent” smile. While guzzling the expensive wine, François listens to Rediger’s offer—he wants François back at the university even though it means converting to Islam.

Rediger discounts atheism using a fairly weak intelligent design argument for a “watchmaker” God i.e. that something as large and complex as the universe couldn’t possibly have come into existence on its own. François, having consumed an entire bottle of wine in short order, doesn’t argue with the ingratiating, eloquent Rediger. The encounter is reminiscent of the debate between Mustafa Mond and the Savage in Brave New World, with Rediger as Mond, and François as an (in this case) intoxicated Savage. Rediger has Mond’s self-assurance and makes his pitch for happiness through submission. He reminds François that it was in his maison particulière that Anne Desclos wrote Story of O, a novel that sums up his anti-individualism philosophy on submission. Whether it is a woman’s submission to a man, or a man’s submission to God, for Rediger “the summit of human happiness resides in the most absolute submission” (209). Here is the crux philosophical question the novel asks, is happiness contingent on submission of will?

A month or so later François attends a reception for a newly rehired former colleague, the sixty-year-old Loiseleur. Initially rendered speechless when the awkward, disheveled Loiseleur announces he is married, François manages ask “To a woman?” to which Loiseleur replies yes, “they found me one . . . A student in her second year” (230). And so, standing there before the slack-jawed François is evidence that he too can expect a new wife—as needed—for the next twenty years if he will convert to Islam and accept Rediger’s offer. On cue, the astute Rediger approaches François who asks bluntly about the kind of wives he might expect, and Rediger flashes his brilliant smile.

.

A Dark Comedy

Houellebecq’s theory of style with respect to prose is utilitarian, and his sentences are straightforward. The tone is conversational, confessional. Houellebecq has written that he has other priorities when writing novels, namely, his characters, and in Submission he has given us a complex, if somewhat familiar protagonist.

Submission is a chimera. It is a quest story, political fiction, philosophical investigation, and dark comedy. Houellebecq is a master of the somber joke, for example: “While I was waiting to die, I still had the Journal of Nineteenth-Century Studies” (39); “It’s hard to understand other people, to know what’s hidden in their hearts, and without the assistance of alcohol it might never be done at all” (129-130); and “I knew next to nothing about the southwest, really, only that it was a region where they ate duck confit, and duck confit struck me as incompatible with civil war” (101). Beyond the one-liner, the novel is a sardonic satire in the Juvenalian tradition of Swift, Huxley, Vonnegut, Céline, and Houellebecq’s contemporary Benoît Duteurtre. Houellebecq’s satire is effective both in exposing our fear of loneliness and asking what sacrifices we are willing to make for a stable society.

In an interview for The Paris Review, Houellebecq said his novel is not a satire, but that it is about “the destruction of the philosophy handed down by the Enlightenment,” and that he chose an academic setting because of the Huysmans subplot. Nevertheless, the characters are, finally, satirized through the choices they make. For example, it isn’t only that Steve converted to Islam so he can collect a fat paycheck, subsidized housing, and young wives, but he agreed to teach Rimbaud converted to Islam as if it were fact and not speculation. It is more than ironic that the system that is the salvation of the state’s problems undermines the integrity of its educators—it is satirical.

Gulliver in the land of Lilliput

Gulliver in the land of Lilliput

Historian Simon Schama said that the purpose of art is to “crash into our lazy routines,” and through François, Houellebecq has certainly created a character that will crash into our complacency. When asked why he wrote Submission, Houellebecq replied that one reason was his atheism seemed “unsustainable” after the deaths he has been faced with. He said:

The clearest point of connection with my other books is the idea that religion, of some kind, is necessary. That idea is there in many of my books. In this one, too, only now it’s an existing religion.

The subtle intelligence of Submission rests in the tension between the surface satire and the undercurrent of sincere self-examination, the quest for an authentic spiritual experience. François’s choice is symbolized in the contrasting worlds of Rediger and Huysmans—on one side: mansions and multiple wives; on the other: the monastery, self-deprivation, and the arduous task of facing doubt while seeking a greater hope—to have heaven on earth now, or wait, patiently, on God.

—Frank Richardson

Frank Richardson lives in Houston and received his MFA in Fiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts. His poetry has appeared in Black Heart Magazine, The Montucky Review, and Do Not Look At The Sun.

Great review, Frank! I admire your clarity and intelligence. You are a writer to emulate!

Thank you for your kind words!