.

Ray Bradbury reminds us that the plot of a story is contingent upon characters chasing after their desires. “Plot is no more than footprints left in the snow after your characters have run by on their way to incredible destinations,” he says in Zen in the Art of Writing: Essays on Creativity. “It is human desire let run, running, and reaching a goal. It cannot be mechanical. It can only be dynamic” (152). What makes the difference, then, between a mechanical plot and a dynamic one? Bradbury suggests that characters will write your story for you if you simply get out of the way and let them go. But I know my characters’ footprints reveal more than just a direct trail to their desires – by charting the plot steps of any story, I can discover what makes a plot dynamic.

I begin by looking up the definition of plot in J.A. Cuddon’s Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory:

The plan, design, scheme or pattern of events in a play, poem or work of fiction; and, further, the organization of incident and character in such a way as to induce curiosity and suspense in the spectator or reader. In the space/continuum of plot the continual question operates in three senses: Why did that happen? Why is this happening? What is going to happen next – and why? (To which may be added: And – is anything going to happen?)

Cuddon defines plot as a pattern of events organized to arouse curiosity and suspense for the reader. He implies that the organization of incident and character must continually incite the reader’s interest; we are not just wondering what’s going to happen next, but we’re left wondering why these particular events are important to the characters and the story. He mentions E.M. Forester’s example of plot versus story to highlight the emphasis on causality: “‘The king died and the queen died,’ is a story. ‘The king died and then the queen died of grief,’ is a plot’” (Cuddon 676). Plot is not just the ordering of events but the ordering should be accompanied by the cause or motive of why an event occurs.

Cuddon’s definition also includes Aristotle’s ideas on plot. In Poetics, Aristotle sees plot as ‘the first principle’ and ‘soul of tragedy’ (Cuddon 676). Aristotle calls plot ‘an imitation of the action,’ as well as the arrangements of the incidents (I learned from Stuart Spencer’s The Playwright’s Guidebook that ‘imitation of action’ is not a physical action but rather “an internal, psychological need.” In other words, we can discuss plot in terms of a character’s need or desire and the related incidents that occur). Aristotle requires the plot to be ‘whole’ (to have a beginning, middle, and end), and he also distinguishes between simple and complex plots: the complex has a crisis action that involves recognition and/or reversal, and the simple has neither (Cuddon 676). Aristotle’s ideal plot, therefore, ends with a moment of revelation to the protagonist that coincides with the protagonist’s sudden change of fortune.

Douglas Glover further explains how dramatic narrative can be developed after the initial desire and resistance have been established. In Attack of the Copula Spiders and Other Essays on Writing, he states: “A character first acts on one impulse and then the other, goes forward, retreats, reels back, makes compromises with necessity, concedes a position out of politeness, ponders his own reactions, realizes that he prefers disorderly love to antiseptic order and changes his behavior” (Glover 26). Put simply, the short story form consists of a character going after something, being blocked from getting it, and changing his behavior to get it another way, and this sequence is repeated over and over. Glover emphasizes that this pattern of conflict must occur such that the opposing forces (A and B) “get together again and again and again” (three being the critical number or minimum). He notes that in the repetition of these poles conflicting, writers are “forced to vary the conflicts in a dramatic and interesting way and you are forced to go deeper into the moral and spiritual complications of the conflict and the relationships” (Glover 27). Glover argues form opens up more possibilities in that writers must create new material related to the same conflict.

In the following discussion on plot, I focus on the repetition or pattern of conflict. In three example short stories, I trace the pattern of character desire and resistance within a story. I am interested in how increasing pressures force characters to “go deeper into the moral and spiritual complications of the conflict.” After I identify the pattern of conflict, I see how each story’s sequence of plot events build to a climax and forces characters to “go deeper” and eventually change significantly.

Charles D’Ambrosio’s “The Point” is about 13-year-old Kurt Pittman who, at his mother’s request, agrees to escort his mother’s friend, Mrs. Gurney, back to her home. Kurt is used to chaperoning drunk locals home, but he quickly realizes that Mrs. Gurney will be difficult. Before they can get across the playfield, she falls on her ass twice and begins to sift through the sand. Kurt finally gets her onto the boardwalk and, despite her protests, dumps her on a wagon to pull her. When he takes a break to breathe, she disappears further down the boardwalk, takes off her nylons, and runs towards the sea. When Kurt repeatedly tries to redirect them to get her home, Mrs. Gurney vomits over herself, babbles on about her age and beauty, threatens to commit suicide, and finally comes onto him by undressing herself, throwing both her blouse and bra into the wind. Kurt at first refuses to look, but he ends up looking at her aging body and expressionless eyes. She presses against him, and he must decide whether to take advantage of the situation or take her home. He decides to bring Mrs. Gurney to her house and tucks her into bed. When Kurt returns home, he can’t sleep and decides to read an old letter written by his father, a Vietnam veteran who has committed suicide. In the letter, the father describes being a medic during the Vietnam War, trying to save the wounded, including a 19-year-old soldier who eventually dies from an explosion. Kurt walks out to the playground, sits in a swing and recalls finding his own father’s body with a bullet wound in the head.

“The Point” is approximately 7,700 words and is told in first-person from Kurt’s point of view. D’Ambrosio breaks up the story into five sections, using line breaks. The major conflict steps between Kurt and Mrs. Gurney (opposing forces A and B) take place in the second, third, and fourth sections. By major conflict, I mean the structure of desire and resistance: Kurt’s desire to bring Mrs. Gurney home and Mrs. Gurney’s resistance to this desire. The first four sections are chronological, moving forward from the party to Mrs. Gurney’s house in about an hour. D’Ambrosio ends the last section with a scene outside of the main plot, a scene that shows Kurt reading his father’s letter and remembering his father’s suicide (thus it is backfill, not plot).

The conflict really begins at the opening of section two when Kurt attempts to walk Mrs. Gurney across the playing field, and Mrs. Gurney plops herself down in the sand, “nesting there as if she were going to lay an egg” (7). She takes off her sandals and tosses them behind her, which prompts Kurt to fetch them. This is Mrs. Gurney’s first action to derail Kurt from his goal. He responds by reiterating his goal (the plot desire): “The problem now is how to get you home.” As if Kurt’s goal isn’t already clear, he thinks to himself, “I’ve found that if you stray too far from the simple goal of getting home and going to sleep you let yourself in for a lot of unnecessary hell.” They start walking again and take “baby steps” across the playing field before Mrs. Gurney falls back “on her ass into the sand” again – another hitch that prevents Kurt from reaching his goal (10).

Once on the boardwalk, Kurt decides to bring Mrs. Gurney home another way: drag the drunkard in a wooden wagon. Despite Mrs. Gurney’s protesting, he somehow gets her into the wagon and starts pulling. When Kurt pauses for a break, he finds “Mrs. Gurney was gone” (11). She slips down the boardwalk, farther from her home, and tries to engage him in drunk talk about Mr. Crutchfield, another local who died earlier that summer. This is Mrs. Gurney’s second major resistance against Kurt’s attempt to bring her home; she no longer sits in the sand but makes it more difficult for Kurt by fleeing the scene.

In section three, Kurt repeats his desire to get Mrs. Gurney home four different times in the span of four pages. The first time is after she pulls her nylons off and he runs and fetches them. He says, “We’re not too far now, Mrs. Gurney. We’ll have you home in no time” (14). She then vomits between her legs, he consoles her with a cigarette, and he again repeats, “We just have to get you home” (15). When she asks him to guess her age, he reminds her, “You’re going home, Mrs. Gurney. Hang tough” (16). When she continues with her drunk talk of how bad life can get, he says, “We need to get you home, Mrs. Gurney … that’s my only concern” (17). In Mrs. Gurney’s four separate attempts to derail Kurt from his goal, he responds with four clear affirmations of his desire.

In section four, Mrs. Gurney poses the most resistance by trying to seduce Kurt. At the beginning of the section, Mrs. Gurney lies down in the sand and takes off her blouse and bra. Kurt looks away and tells her they should go. When she tries to get him to sit, he thinks: “I’d let us stray from the goal and now it was nowhere in sight. I had to steer this thing back on course, or we’d end up talking about God” (19). He says to Mrs. Gurney, “This isn’t good. We’re going home,” once again repeating his goal (for the sixth time, not counting the times he thinks it). He also mentions he can see the house, observes it’s only “one hundred yards away,” and that they’re “so close now” (19-20). Mrs. Gurney, however, tries to engage him in conversation again by offering her house to him after she dies, threatening she’ll kill herself, and babbling about how she met her husband – all her ways of resisting going home.

When none of Mrs. Gurney’s attempts seem to faze Kurt, she tries to seduce him. Mrs. Gurney steps closer and leans in – he resists by saying, “Mrs. Gurney, let’s go home now” (his seventh time). He looks into her “glassy and dark and expressionless” eyes, and he then feels her hand brush the “front of his trunks” (23). He wonders whether he should go “fuck around” and “get away with it.” In the climactic moment, he chooses to resist Mrs. Gurney and hands her his t-shirt to cover up. They move away from the shore and cross the boardwalk to Mrs. Gurney’s home. The plot ends when Kurt leads Mrs. Gurney by the elbow into her house.

Kurt comments at the beginning of his journey that “everything … had a shadow and this deepened the world, made it seem thicker, with layers, and more layers and then a darkness into which I couldn’t see” (9). I had a similar experience of seeing layers and more layers of this story after I separated the plot from the rest of the story. The repetition of the same desire and resistance makes up the main conflict: Kurt wants to take Mrs. Gurney home, but she does not want to go home. Kurt repeating his simple desire versus Mrs. Gurney’s increasing resistance drives the story forward – there’s nothing unclear about what he wants (since he says it seven times). The protagonist doesn’t hint at or suggest his desire –Kurt uses the phrase “I want…” to make the reader aware of his concrete desire.

Glover states that the repetition of the same desire and resistance forces writers “to vary the conflicts in a dramatic and interesting way … [writers] are forced to go deeper into the moral and spiritual complications of the conflict and the relationships.” Kurt’s desire to take Mrs. Gurney home may seem humdrum or routine at first – he doesn’t have any stake in his relationship with Mrs. Gurney since he’s just doing his job. The tension rises with Mrs. Gurney’s increasing resistance: she first falls over, then wanders away, then takes off her nylons, and starts to babble nonsense. But her dialogue in the third section begins to take on an ominous tone: a threat to kill herself is more loaded than her previous statement of how bad life can get. Notice how the tension increases in the following dialogue right before the climax:

“I’m thirsty,” Mrs. Gurney said. “I’m so homesick.”

“We’re close now,” I said.

“That’s not what I mean,” she said. “You don’t know what I mean.”

“Maybe not,” I said. “Please put your shirt on, Mrs. Gurney.”

“I’ll kill myself, “Mrs. Gurney said. “I’ll go home and kill myself.”

“That won’t get you anywhere … You’d be dead … then you’d be forgotten.”

…

“My boys wouldn’t forget” (21).

This dialogue serves two functions: 1) The back-and-forth between opposing forces A and B creates the suspense that plot should incite (according to Cuddon’s definition), and 2) The content of the dialogue foreshadows Kurt’s flashback at the end of the story since Kurt did not have any forewarning of his father’s suicide, and he could never forget the bloody and emotional mess.

These previous plot steps build to the climactic moment in which D’Ambrosio must escalate Mrs. Gurney’s resistance dramatically: the drunk woman takes off her bra and tries to seduce Kurt. Her actions force Kurt to “go deeper” into himself and reveal what Glover calls the “moral and spiritual complications of the conflict and relationship”– on the surface, Kurt must decide whether to stick to his goal of getting Mrs. Gurney home or give in to her seduction. On a deeper level, the adolescent questions his beliefs by asking himself, “What is out there that indicates the right way?” (23). In a later flashback, Kurt mentions he misses “having [his father] around to tell [him] what’s right and what’s wrong, or talk about boom-boom, which is sex … and not worry about things” (31). Kurt finally expresses his emotional need for his father after the plot ends, but the main plot between Kurt and Mrs. Gurney allows us to see how his internal conflict plays out in their actions.

The main conflict between Kurt and Mrs. Gurney only takes up three of five sections. D’Ambrosio could have ended the story after section four when Kurt gets Mrs. Gurney home, but the author ends with the backstory of Kurt’s father – specifically, the ending focuses on the father’s mission as a medic during the Vietnam War and his suicide. The father’s story ties in with Kurt’s story because they both have a “mission” to carry out: the father helped the wounded in Vietnam, and Kurt helps the drunk (and wounded) in his hometown. Kurt considers himself a “hard-core veteran” ever since his father assigned him the job when he was 10 years old (5). Both Kurt and his father mention the “job” and what happens when you “lose sight” of the job or “stray too much from the goal” (28). D’Ambrosio includes the backstory of Kurt’s father to resonate with the main plot structure: Kurt’s “mission” to escort Mrs. Gurney home.

By extracting the plot from the rest of the story, I notice what is left on the page: the subplot of Mr. Crutchfield’s death, the root image of the black hole that splinters into white image patterns, Kurt’s internal monologue expressing thematic motifs, and the backstory of Kurt’s father’s suicide. I mention these non-plot devices to point out that if I hadn’t previously traced the plot beforehand, I would have naïvely assumed that the father’s story or Kurt’s flashback to his father’s suicide were all part of the main plot instead of devices that enhance the plot. In many stories, ancillary devices can echo the structure of the main plot, which, in this story, deepen the meaning of the protagonist’s desire to get his job done. “The Point” portrays character desire and resistance mostly through dialogue and action, but the next story shows how another writer captures the main plot in internal monologue.

In “Under the Surface” by Slovene writer Mojca Kumerdej, the narrator is a woman who desires to be alone with her lover and have him all to herself. When she sees an attractive woman flirting with him, she gets pregnant in hopes to keep him forever. She gives birth to a daughter, but the new daughter seems to steal her lover’s attention. The little girl interrupts their Sunday mornings in bed, and on the narrator’s birthday, they celebrate as a whole family – not romantically and privately. One day on vacation, the narrator goes to up to the house while her lover and daughter remain by the shore. She watches her lover napping in the sun while the daughter gets dragged out into the ocean. She lets her daughter drown, drinks brandy, and falls asleep on the bed. Her friend wakes her up and tells her the news. The narrator reflects that she may have let her daughter die, but the narrator now has her lover all to herself.

The story is 3,000 words and is written as an interior monologue mixed in with dramatic monologue. A retrospective narrator reveals to the reader her secret that she withholds from her lover, but Kumerdej uses the second person “you” to direct the monologue at the narrator’s lover. This story covers the span of more than eight years (pre-baby years, five years with child, and three years after the child’s death). Kumerdej also uses a conventional circular structure to the story: the beginning of the story is also the end of the story that takes place three years after the narrator’s daughter drowned. The rest of the story is told chronologically and focuses on the narrator’s relationship with her lover and daughter.

The plot, the pattern of desire and resistance, is created from the narrator’s desire to be alone with her lover and the apparent threats that the narrator sees as a danger to her relationship. I say “apparent” threats because we only see the story from the narrator’s perspective (from an outsider’s perspective, she needs professional help to separate her delusions from reality). The pattern of conflict plays out in the following steps: 1) the narrator has a baby to gain her lover’s attention, but the little girl cries and steals the spotlight, 2) the narrator wants to sleep in with her lover on Sunday mornings, but the little girl physically gets in the bed, 3) the narrator wants to be alone with her lover on her birthday, but the lover wants the whole family together, and 4) the narrator wants to be alone with her lover in the future so she lets her daughter drown.

The set-up of the conflict starts when the narrator sees another woman flirting with her lover by “calculatedly moving around [him] … and “licking her lower lip” (7). The narrator never thought to have a baby – what two people in a relationship who love each other usually do – until now. The real action starts in paragraph two when the narrator announces she “had to take action” and get pregnant (7).

But when the baby comes, the narrator notices that the child doesn’t solidify their love but instead comes between them. The narrator observes that the lover first kisses and plays with their child, leaving the narrator to “wait [her] turn” (8). Even at night when the narrator is woken up by the daughter’s “piercing screams,” the lover rarely gets up to spend time with the narrator. The narrator becomes so angry that she slaps the child, which in turn angers the lover. She considers her baby competition, which drives the couple further apart thus propelling the plot forward.

In the next plot step, the narrator describes again how the daughter intrudes on her alone time with her lover. On Sundays, which were usually reserved for sleeping in, the little girl would run into the room and jump on the bed to hug her father. The narrator thinks: “Our time was becoming more and more the little one’s time, she was the one giving rhythm to our mornings and nights. You didn’t want us, as I suggested once, to lock ourselves in” (10). When the narrator tries to regain alone time with her lover, the lover responds, “That isn’t good … she needs us.” This prompts the narrator to ask, “But what about us?” The narrator feels reproached by him and looks “towards the door in fear … wishing not to hear the tiny footsteps coming towards our bedroom” (10).

In a third plot step, on the occasion of the narrator’s birthday, the narrator suggests to her lover that she wants to celebrate her birthday differently, just “the two of us together” (11). She suggests that they drop the girl off with his parents, but the lover opposes the suggestion “both times.” The narrator assumes he prefers to be with the “whole family,” and he acts as if his parents would be insulted if they didn’t invite them. Each time the narrator tries to be alone with her lover, she feels her lover straying further away.

The last five pages of the nine page story focuses on how the narrator finally gets her lover all to herself: by letting her daughter drown in the ocean and allowing the lover to take the blame. She watches her daughter chase after an inflatable dolphin and get dragged out to sea. The narrator knows she could alert her lover by screaming, but at that moment she “saw a chance for things to be the way they used to be. Me and you, the two of us alone …” (13). The plot ends when the daughter’s body is “sucked into the depths” (13). In this moment, the narrator achieves her goal at the expense of a dead daughter and a guilty conscience that she suppresses by taking showers.

When I met Mojca Kumerdej in Slovenia this past summer, she mentioned that her readers – regardless of what country they’re from – want to argue about the mother’s actions in “Under the Surface.” Kumerdej said many readers attack the narrator because they think the narrator’s actions are highly unbelievable – “no mother would ever do that!” they claim. I would argue that the narrator’s obsessive desire partially explains her psychotic actions (or rather lack of action to save her daughter). A closer look at the plot, however, shows a carefully crafted sequence of events that makes the narrator’s actions seem justified in her own mind.

Unlike “The Point,” Kumerdej’s chosen point-of-view brings us into the mind of the narrator, in which we are only presented with her perspective. Plot is not entirely made up of scene as it is in “The Point” where D’Ambrosio uses dialogue and actions to express desire and resistance. Instead the narrator in “Under the Surface,” in a stream-of-consciousness-like confession, proves how far she will go to be alone with her lover. At first glance, the story appears to be a long rambling about the narrator’s undying devotion to her lover (she says she loves him five different times in the span of the story). But the story still includes a clear desire and resistance pattern; the narrator articulates immediate obstacles that become clear plot steps creating tension in the story. The baby arrives, cries and steals attention, grows up and physically and emotionally gets in the way of the narrator’s relationship with her lover. In these plot steps, Kumderdej builds to a crisis action that forces the narrator to commit the unthinkable. The only “logical” action in the narrator’s mind is to permanently get rid of her daughter – as soon as the narrator has the opportunity, she lets her child drown in order to have her lover all to herself.

The narrator’s internal monologue at critical points in the story adds even more tension to the main plot. Kumerdej creates a pattern in which every other paragraph leading to the climax ends with the narrator’s intense desire for her lover and the sacrifices she made:

When for the first time you put your hand on my stomach I knew I had you, and that’s when I decided to have you forever, wholly and completely, without intermediary, disturbing elements that could jeopardize our love (second paragraph).

But no woman in the world is capable of loving you as much as I do, no woman in this world would be capable of doing what I did … (fourth paragraph).

And precisely that is what I did for you, and once in my life took away what meant the most to me … (sixth paragraph).

These lines are not directly part of the main plot structure, but the narrator’s repeated thoughts emphasize her fixated desire. The narrator justifies killing her daughter as a form of her devotion and love. To clarify, the opposing forces aren’t the narrator and her daughter but rather the narrator’s desire to be with her lover (A) versus the narrator’s apparent threats in her mind preventing her from having her lover all to herself (B), which repeat in four distinct steps.

In the climactic scene of “The Point,” the plot steps lead up to a moment that forces Kurt to take action: he ultimately chooses to rebuff Mrs. Gurney’s romantic offering and takes her home. In “Under the Surface,” the plot steps lead to a climax in which the narrator chooses not to take action and leaves her daughter to drown: “I didn’t do anything – and by doing so did everything” (7). Similarly in both of these climactic scenes, each character wrestles internally, even if briefly; both D’Ambrosio and Kumerdej include the characters’ internal thoughts that allow us to see how the pressure forces them to change (or not). Kumerdej writes: “At that moment, I saw a chance for things the way they used to be. Me and you, the two of us alone … I was watching the scene, and it seems to me I didn’t feel anything. No pain, no kind of fear, I was only watching what I thought as things happened” (13). Interestingly the narrator doesn’t “feel anything” in this moment but expresses her emotional transformation after the plot ends.

After the narrator has her lover to herself, Kumerdej includes five short paragraphs that reveal the narrator’s change of emotions. The narrator still desires her lover, but she’s also haunted by the image of her drowning daughter dragging her “into the depths.” The narrator feels isolated because her lover will never know the truth, and she wakes up in “terrifying pain” from guilt-ridden nightmares (14-15). Both D’Ambrosio and Kumerdej could have ended their stories when the plot ended, but they chose to include backstory and internal monologue that illustrate how their characters transform after the crisis action occurs. In one last story, we see again how the sequence of plot events builds to a climax that significantly changes the characters, especially in regards to their emotional and mental state.

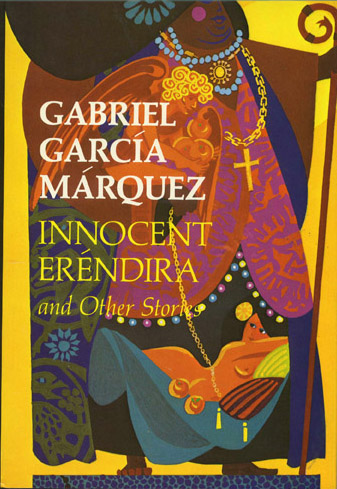

Gabriel García Márquez’s “The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother” is a novella about fourteen-year-old Eréndira who survives her grandmother’s cruelty and, with the help of a young man, becomes free. The story begins in the grandmother’s ornate mansion where Eréndira exhaustedly completes her endless chores. When she falls asleep, the wind knocks over a candlestick she left burning and destroys the property and the grandmother’s possessions. The grandmother decides to prostitute the girl so she can pay off an impossible million-peso debt she has incurred by causing the fire. During her servitude, after countless encounters with men and paying customers, Eréndira meets a young man Ulises who falls in love with her. Among other adventures, a group of missionaries kidnaps Eréndira to protect her, but the grandmother pays an Indian boy to marry Eréndira and free her from the mission. Having fallen in love, Ulises disappears from the story for a while but inevitably returns to run away with Eréndira, but they don’t get far; the grandmother captures Eréndira and chains her to a bed to prevent a future escape. Eréndira entertains the thought of killing her grandmother with boiling hot water but has no confidence in her ability to kill her oppressor. Ulisses returns, and she begs him to murder her grandmother. After two failed attempts with rat poison and a bomb, Ulises slaughters the grandmother with a knife, and the old woman finally dies. Instead of turning to Ulises, Eréndira runs in the direction of the wind and is never heard from again.

The novella is approximately 16,200 words and is divided into seven sections with line breaks. Márquez uses a third-person omniscient narrator with the exception of a two-page transition to a first-person narrator who tells his personal account of seeing Eréndira and her grandmother with his own eyes. Unlike “The Point” and “Under the Surface,” we get to see, from a limited distance, the perspective of multiple characters. Márquez tells the story chronologically (Eréndira is 14 at the beginning and 20 by the end), and his use of the techniques of magic realism creates a fable-like quality. The story also carries the “wind of misfortune” motif that governs Eréndira’s actions– first it blows at Eréndira and causes the fire, then the wind brings along the missionaries and also incites her to run away, and, in the end, she runs into the wind and beyond it.

The main plot takes up only a small portion of the entire text and concentrates on Ulises’s and the grandmother’s conflict over Eréndira. Ulises falls in love with Eréndira, but the grandmother prevents him from being with her. The following plot steps occur between Ulises (A) and the grandmother (B): 1) Ulises wants to sleep with Eréndira, but the grandmother denies him entry into the tent so he sneaks in and sleeps with the girl anyway, 2) Ulises falls in love and convinces Eréndira to run away, but the grandmother captures Eréndira and dog-chains her to a bed, and 3) Eréndira magically summons Ulises, and he attempts to rescue her by killing off the grandmother (third time’s the charm). With the grandmother dead, however, Ulises doesn’t end up with Eréndira since she runs into the wind and disappears forever.

Márquez delays the main plot, the pattern of desire and resistance, until the third section of the story. The grandmother’s unrelenting abuse of Eréndira seems like a one-sided conflict until Ulises, the son of a Dutch farmer and Indian woman, poses a threat to the grandmother’s scheming. In the first plot step, Ulises lines up with the other soldiers to sleep with Eréndira, but the grandmother prevents him from seeing her: “No, son … you couldn’t go in for all the gold in the world. You bring bad luck” (298). He later sneaks into the tent and manages to sleep with Eréndira while the grandmother talks in her sleep. Eréndira loves Ulises “so much and so truthfully” – their connection solidifies the continuation of the main conflict. The two lovers are separated after this point since the missionaries kidnap Eréndira in order to protect her.

In the second plot step, Ulises’s mother notices he’s “lovesick,” and he sets off to trek across the desert and reunite with Eréndira. When Ulises finds Eréndira sleeping with her eyes open, he tries to convince her to run away by tempting her with his father’s homegrown diamonds, a pickup truck, and a pistol. He tells her, “We can take a trip around the world.” Eréndira says, “I can’t leave without [my] grandmother’s permission,” but that night her instinct for freedom leads her to flee with him (316). Their romance is short-lived; the grandmother initiates a car chase to get her granddaughter back. The grandmother then dog-chains Eréndira to the bed slat so the girl can no longer escape (325).

Ulises doesn’t reappear until six pages later when Eréndira calls out Ulises’s name “with all the strength of her inner voice.” This time, Ulises crosses the desert and instinctively (or magically) knows where to find her. While the grandmother sleeps, Ulises kisses Eréndira in the dark and they both hold “a hidden happiness that was more than ever like love” (329). After sobbing in her pillow, Eréndira asks him to kill her grandmother, and he says for her he’d “be capable of anything.” This reunion sets Ulises up to encounter the grandmother for a final time.

In the last major plot step, Ulises and the grandmother meet face to face, and he attempts to kill her on three separate occasions. First, Ulises lies to the grandmother and says he’s come to apologize on her birthday. The grandmother concedes and devours his cake that’s secretly baked with a pound of rat poison. Instead of dying, the old whale sings until midnight and “went to bed happy” (332). Next, Ulises tries to blow up the grandmother with a homemade bomb, and the woman was left with her wig singed and her nightshirt in tatters “but more alive than ever” (334). In Ulises’s last attempt, he grabs a knife and stabs the grandmother’s chest, her side, and a third time for good measure, but she doesn’t go quickly and yells, “Son of a bitch … I discovered too late that you have the face of a traitor angel.” Covered in the grandmother’s green blood from head to toe, Ulises manages to cut open her belly, avoids her lifeless arms, and gives “the vast fallen body a final thrust” (336). The plot ends when the grandmother finally dies, but Ulises doesn’t end up with his love since Eréndira runs into the wind never to be heard from again.

As I mentioned earlier, Glover states that plot is a repeating desire-resistance pattern between two poles A and B. Readers may at first confuse the grandmother’s abuse and sexual exploitation of her granddaughter as the main plot. It’s not. Márquez begins “Innocent Eréndira” with a lengthy dramatic set-up that isn’t part of the main plot structure: a meek, soft-boned girl cannot escape her grandmother’s horrible exploitation. In the narrative set-up, Márquez keeps our interest by pushing the limits of the grandmother’s brutality: she negotiates Eréndira’s virginity for 220 pesos, she orchestrates a bazaar – complete with musicians, a photographer, and a circus tent – to attract hundreds of solicitors, and not until Eréndira shrieks like a frightened animal and thinks she’s dying does the grandmother give her a break. Eréndira doesn’t fight back and consequently doesn’t pose a formidable resistance to her grandmother. Márquez can only sustain readers’ interest for so long (before they ask, “will anything else happen?”) and introduces Ulises in the third section as the real resistance to the grandmother.

Once Márquez establishes the two opposing forces in conflict, he increases the pressure and varies the conflict in an interesting way (he also interrupts the plot steps to reinforce the grandmother’s malevolent behavior and the granddaughter’s helplessness to escape). Notice that in the first two plot steps, Ulises tiptoes and sneaks behind the grandmother’s back in order to physically interact with Eréndira. In these scenes, Ulises doesn’t face any real confrontation with the grandmother other than their first brief encounter, but the old woman and her command over Eréndira still pose a threat. Márquez intensifies the pressure when Ulises comes into direct physical contact with the grandmother; the boy quickly fabricates a story in order to save himself and carry out the grandmother’s murder. This confrontation forces Ulises to take greater risks: he poisons her, fails, blows her up and fails again. Ulises’s actions follow Glover’s definition of plot when the character “first acts on one impulse and then the other, goes forward, retreats … realizes that he prefers disorderly love to antiseptic order and changes his behavior.” Only when Ulises notices Eréndira’s “fixed expression of absolute disdain, as if he [doesn’t] exist,” does he finally carry out the murder. In this climactic moment, Ulises has the choice to either kill the grandmother in order to win Eréndira’s love or he can retreat – he, of course, chooses “disorderly love” over “antiseptic order” and kills for love.

Just like “The Point” and “Under the Surface,” the plot ends with the crisis action, and the author includes the transformation of characters in the aftermath of the climax. In a final scene, Márquez describes Eréndira watching with “criminal impassivity” the final fight between Ulises and the grandmother. In fact, the girl embodies “criminal impassivity” throughout the entire story. Not until after the grandmother dies does Eréndira suddenly “acquire the maturity of a [20-year-old]” and escapes into the wind where “no voice in this world could stop her.” Eréndira’s bold action is the exact opposite of the once cowering, servile girl who couldn’t live on her own freewill. Ulises, on the other hand, suffers greatly after he kills the grandmother. The crisis action leaves him “lying face down … weeping from solitude and fear” since he has just lost the love of his life and is “drained from having killed a woman without anybody’s help” (337). Márquez deliberately arranges the plot steps to finally reveal the emotional and dramatic reversal and recognition that the characters experience.

Márquez’s novella reads like a fairytale because of his use of magic realism (not to mention the similar overtones to the Cinderella story-line: note the use of threes – three plot steps, three murder attempts, very much like a fairytale). In particular, Márquez utilizes magic realism to bring characters back together “again and again and again” in order to continue the main plot. For instance, when Ulises falls in love, every glass object he touches turns blue; Ulises then runs to find Eréndira and tempts her with his father’s magical oranges that contain “genuine diamonds.” Ulises also reunites with Eréndira for a third time when she summons him by calling out his name; in his plantation house, he hears her voice “so clearly” that he knows exactly where to find her. In a last example, Márquez uses magical realism to prolong, rather humorously, the conflict between Ulises and the grandmother. Instead of the grandmother dying after Ulises’s first (or second) murder attempt thereby ending the plot, the old woman lives on to croon her songs and babble in her sleep. Ulises even knifes her open and gets splattered with her green blood, but she’s not yet dead. Although Márquez seems to randomly pepper magical realism throughout the story, he strategically uses the technique to reunite characters and advance the plot. These moments defy our expectations and incite the very suspense and curiosities that plot should stimulate. Márquez’s story exemplifies how imaginative qualities, engaging characters, the combination of horror and humor, and a narrative set-up can coexist with the main plot structure so long as it sustains the reader’s interest.

The example stories I analyze may follow the same form or pattern, but the writers construct the plot in three distinct ways. In “The Point,” the plot is straightforward – Kurt and Mrs. Gurney battle it out until Kurt overcomes her resistance. The unreliable narrator in “Under the Surface” muddles the plot steps in her internal monologue, but she still articulates her desire and competition. In “Innocent Eréndira,” the plot is delayed for nearly a third of the story and yet still manages to mold into the same structure in the end. Plot, however, is not the same mechanical formula applied to every story – plot is a dynamic form that we identify as a pattern of desire and resistance between two opposing forces, but infinitely varied by each writer.

These stories were also originally written in different languages (English, Slovene, and Spanish, respectively), which suggests that in any culture (and time period), plot translates to the same pattern. Why do stories follow this particular pattern of desire and resistance? If plot is to “induce curiosity and suspense” in the reader, writers must invent new ways for characters to pursue their desires, charge through increasing resistance, and come out of a crisis action significantly transformed. No matter what the native language or nationality is of a reader, he or she will inherently invest in characters who chase after their desires, fail, get up and try again. We root for characters who, in our minds, allow us to imagine what it is like to step into their skin and travel to “incredible destinations.”

— Nicole Chu

Works Cited

Ambrosio, Charles. “The Point.” The Point and Other Stories. Boston: Little, Brown, 1995. Print.

Bradbury, Ray. Zen in the Art of Writing: Essays on Creativity. Santa Barbara: Joshua Odell Editions, 1994.

Cuddon, J. A., and Claire Preston. A Dictionary of Literary Terms and Literary Theory. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 1998. Print.

García Márquez, Gabriel. “The Incredible and Sad Tale of Innocent Eréndira and Her Heartless Grandmother.” Collected Stories. New York: Harper & Row, 1984. Print.

Glover, Douglas H.. Attack of the Copula Spiders and Other Essays on Writing. Emeryville, Ont.: Biblioasis, 2012. Print.

Kumerdej, Mojca, and Laura Turk. “Under the Surface.” Short Stories Collection:

Fragma. Berkeley, Calif: North Atlantic Books, 2008. 7-15. Print.

.

Nicole Chu is about to receive her MFA in Fiction from Vermont College of Fine Arts. She is originally from California and currently lives in New York City, where she teaches English Language Arts at a public school in the Upper West Side.

.

I just read the first sentence of the essay and somehow it reminded me of the opening of Godhard’s “Le Mepris” (Contempt) where he quotes French film critic Andre Bazin: “The cinema substitutes for our gaze a world more harmonious with our desires”. I guess human desires are motivations for all things. Tom