The British writer Graham Greene allegedly wrote five hundred words a day and not one more. He met his quota by noon, leaving him free in the afternoon to tipple martinis and hustle the disaffected wives of diplomats and spooks in various exotic hotbeds of the Cold War. It was the writer’s life writ large.

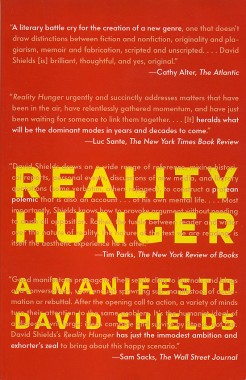

We are now living in the fiction writer’s age scribbled small. There are more writers, it seems, emerging from more MFA programs only to serve fewer readers. And writers seem to have lost confidence in their task, both to have a life away from writing or having a writing life that attract readers. One guy who’s got this sorry state of affairs beat is David Shields. Over the past fifteen years, Shields has written/co-written/co-edited—authored?—eight deceptively accessible experiments in written performance art that combine autobiography, free associating erudition, and cultural scavenging. With impeccable timing, he turned his back on fiction, only to create his own genre of writing that, one suspects, has more than a touch of fiction to it.

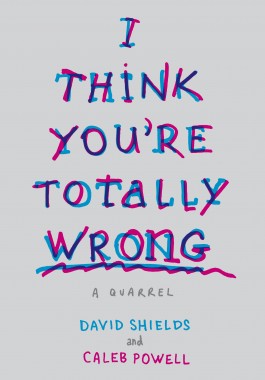

In his compelling new book, I Think You’re Totally Wrong: A Quarrel, Shields uses a former student, Caleb Powell, as a shadow boxer for Shields’s performance of self. The two steal away to a cabin, surrounding parks and small towns outside of Seattle for four days to muse on domestic life, American military misadventures, writing, masculinity, mortality, and making sense of the daily absurdity of existence. Once you’re past the thudding metaphor of a chess match on the first day, the two reveal themselves as highly complementary and intriguing battlers. Powell is almost a Portlandia cartoon, a gabby stay-at-home dad with a writing career stuck in second gear, various pop culture obsessions, and a hard-charging wife who was once married to a closeted homosexual. Shields, in sharp contrast, is a low-temperature nudnik who knows he’s playing a game that he’s sure to win. He’s prickly, dismissive, yet almost always on the money. Even when Shields says he’s ready for bed, you suspect that it’s more of a tactic than the truth, as if he’s able to shut down his confessional mode while Powell suffers a compulsion to keep blabbing. These are men for whom cool is a quixotic quest yet their very lack of cool is exactly what makes them such vexing and entertaining company on this anti-Gonzo road trip.

—Timothy Dugdale

N5

Timothy Dugdale (TD): What is about the chatting buddy concept that attracted you? I have to say I’m struck just by how skittish Caleb is compared to your much more measured, albeit calculating sense of self. He seems much more beholden to his generation’s anxieties and fetishes and even sexual confusion.

David Shields (DS): I’ve always loved the idea of the book as argument—going from Socrates v Plato to Rosencrantz & Guildenstern to Didi and Gogo to Car Talk. Dionysus v Apollo. Life v Art. A self and other. The soul and its doppelganger. I was very interested in having someone call me out on my aesthetic and all the choices I’ve made in my life; I wanted to see if I could defend myself to self, and to my anti-self, Caleb.

I’m not sure about generational differences; Caleb is only 13 years younger than I am. It’s more what you call “calculating”; since my book Remote was published nearly twenty years ago, I’ve been fashioning my life and myself into a stylized self.

TD: Do you think the concept is currently having “a moment” in the culture and why?

DS: I see it everywhere, e.g., the recent movie Land Ho!, but I always just assumed it was my antennae being particularly attuned to this framing device. If it is having a moment, I wonder why that might be—perhaps having to do with the virtuality of culture and the way in which we’re all talking to a screen-self?

TD: There’s Steve Coogan road trip thing from Britain where he and a friend drive around to various Michelin starred restaurants and have conversations on camera. They’re pretty twee but interesting.

DS: Well, sure, we talk at length about Coogan and Brydon in the book and in the film. Other examples: Sideways, the DFW-Lipsky book [Although Of Course You End Up Becoming Yourself] (which is also apparently becoming a film) so many other examples. I wonder if it’s influenced by radio. I’m weirdly addicted to sports talk radio especially when the two hosts have or pretend to have competing personalities. What is it in the culture that craves this? I think it’s American loneliness. It’s a way to get to “the other.” The whole idea of “no one goes bowling anymore.” Here’s a chance to break out of the carapace of selfdom.

TD: I heard an interview with William Shatner in which he said there are really two Shatners, the performative one (William) and the “real” one (Bill), yet any time I read a profile of him, he is clearly performing for the writer because invariably the theatre of the profile takes them into public spaces where Shatner must be Shatner. How much “real” Shields is in this book? I know at the beginning you attest to the goal of putting it all out there.

DS: I am putting it all out there, as is Caleb, but it’s undeniably a performance. First, when we talked, we were performing for each other. Then we edited the thing to within an inch of its life. And I was hyper-aware in the edit not only of the life-art debate but also of the ways in which each of us is representative of a certain way of being; as such, each of us was performing a thematized role (again, Life v Art), and we knew what role to play and keep playing and complexify. It’s both completely unbuttoned and a formalized unbuttoning.

TD: You’ve said that the camera had no real effect on you but, looking at it now, how did the camera influence your “performance”?

DS: James Franco’s film adaptation was done two years later; we had hoped, with the film, to replicate the originating debate, but we wound up throwing out the entire argument when a major argument broke out on the set between me and James and Caleb—over what could and couldn’t be “used” from real life in the movie—and the argument was the perfect holding tank for an even “rawer” life-art debate.

TD: In a sense, James Franco is emerging as a sort of “reality hunger” avatar and you’ve clearly made a connection to him. I know you don’t often write about this, but what role does a common background as secular Jews play in your relationship?

DS: Hmm. That’s interesting. James and I are from the same part of the country—the Bay Area, in particular, the “Peninsula.” I grew up in San Mateo and James grew up 20 minutes away in Palo Alto. He’s more than twenty years younger than I am, but perhaps being secular Jews has something to do with the connection. James was my student at Warren Wilson College, and it’s my sense that we connected via our shared interest in emotional nakedness, awkwardness, revelation, self-exposure.

TD: What other avenues of your work are you exploring with James Franco? What are the targets of these collaborations?

DS: I’m working with James on two other films right now: an adaption of my book Black Planet. This is sort of Spalding Gray meets Errol Morris meets TED talk meets Doug Stanhope. I try to explore the irreducibly tragic nature of human tribalism, comparing 1994 and 2014, the Sonics and Seahawks, America then and now. The film is called Return to Black Planet: The Dream of a Unified Field Theory (of Love). I’m sort of excited about it, nervous about it. It gets into some extremely uncomfortable territory. We’ve shot this film and are editing it now. We’re also adapting The Thing About Life is That One Day You’re Dead into a film. I’ve written the film treatment with a few other people, and we’re preparing to shoot it sometime this fall or winter. It’s a movie about James and me trying to make the movie and, in so doing, we explore the very complex legacies of our fathers, the drive to create art, our fear of madness, and our being half in love with easeful Death, to quote my good friend John Keats, isn’t it? We’ve finished the film of Totally Wrong, I’ve watched it and love it, and we’re expecting it to be released sometime in 2015.

TD: Can the performance of autobiography be “too much” sharing to the point that even the most gut-wrenching details or piercing insights become banalities?

DS: Of course; 95% of “memoir” is just that; I’m not interested in memoir, though, as I say to Caleb; I’m interested in the book-length essay, especially book-length collage. There’s the difference between life and art in the contrast between, say, Sarah Manguso’s The Guardians and everybody else’s grief memoir.

TD: Collages, to my mind, require a fair bit of work from the reader to bring the work together in their own mind. Is that your aim in these projects?

DS: I’ve been working in literary collage for twenty years. Literary collage reaches back to Heraclitus and up to Manguso, whose amazing new book, Ongoingness, is forthcoming soon. It’s an ancient form with particular application now, having to do with hyperdigitization, multiplicity of platforms, and warp speed of culture. Collage, as I like to say, is not a refuge for the compositionally disabled. (Nor for the readerly disabled.) It’s a demanding form for reader and writer, but then so is Christian Marclay’s The Clock.

[youtube]https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xp4EUryS6ac[/youtube]

TD: What do you see as the future of celebrity in an era of “reality hunger”? Or have we moved so far beyond the “star” that we now only have “quasars”, as James Monaco would put it?

DS: I like that—quasars, not stars, but what does it mean? Fifteen seconds of fame rather than fifteen minutes? You and I originally traded email when you read my book Remote: Reflections on Life in the Shadow of Celebrity in 1996, but I’m not hugely interested anymore in celebrity as a topic. I think digital culture has completely reshuffled what people think about “celebrity,” don’t you? Everybody is a star of their own selfies.

TD: I find the photo bomb more interesting than the selfie.

DS: Exactly. The photo bomb is politics by proxy.

TD: It’s a calculated imposition on the individual selfie and an indictment of the selfie as cultural practice.

DS: I suggested to Franco that he ask everyone who takes a selfie with him (which is pretty much everyone he ever encounters) to send their selfies to a dedicated site, then he could curate this site into a self-portrait in a convex mirror and also a meditation on quasars (see above).

TD: I know you’re a fan of Bill Murray and I’m wondering what you think of his ongoing public performance as a “reality hunger” fairy godfather, popping up here and there in strangers’ events. I remember him as being far more angry and less sad or crypto-Buddhist.

DS: Isn’t he endlessly cashing in, though, on his celebrity in this way? How else would he enter these events? The rage is still there; he’s furious, which is what gives the comedy its edge. Everything I know I’ve learned from comedians—from the Book of Job to Amy Schumer. I wrote a very long essay about Murray maybe a dozen years ago in which I explored how he transforms gloom into antic comedy; the latter is, of course, only an instantiation of the gloom. The best thing Murray ever did, in his own estimation, is his guest color commentary at a Cubs game. I have the videotapes if you want to watch. It’s really lovely: he’ll talk for five minutes about a hot-dog wrapper making its way through the stands.

TD: You say you’ve lost interest in fiction, but there must some kind of fiction that is able to so artfully be the “lie that tells the truth” that it is better than the truth or reality?

DS: Yep, I’m not interested in truth or reality per se. I’m interested in work that frames itself as essay. The essay has as much poetic imagination as any novel, but it’s organized as a meditation. Every book-length essay from Thucydides to Annie Ernaux is full of poetic liberty-taking. What I like is a dwelling down in consciousness—the attempt to alleviate loneliness via “self-deconstructive nonfiction,” to use a wonderful term of Alex Pappademas. I love a lot of novels, but they’re all almost exclusively consciousness-drenched works: Melville; Proust; Sterne; etc.

My argument—some of this comes via David Foster Wallace—is that we’re existentially alone on the planet; I can’t know what you’re thinking and feeling. And you can’t know what I’m thinking and feeling. Writing, at its best and most serious, isn’t narrative entertainment but is a bridge constructed across the abyss of this human loneliness. The work that I love best, that I think constructs the most exciting and durable bridge, is work that is manifestly—in its every line—about how the writer is solving or not solving the question of being alive. Samuel Johnson said that a book should either allow the reader to escape existence or teach him how to endure it. And I’m gigantically in love with books—from Lucretius to Simon Gray—that attempt to do the latter. That’s the tradition to which I’m trying to contribute, for better or worse.

—David Shields & Timothy Dugdale

N5

Timothy Dugdale is a veteran copywriter and brand manager. He writes existential novellas and poetry as well (http://dugdale.atomicquill.

.

.