Lynne Tillman by David Shankbone.

Lynne Tillman by David Shankbone.

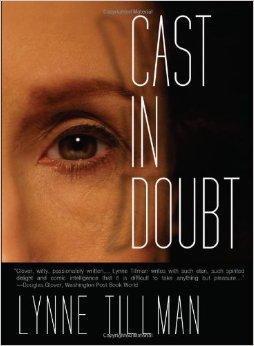

Here’s a review I wrote of Lynne Tillman’s 1992 novel Cast in Doubt. Those were the days when I was a young, hungry whipper-snapper trying to review in all the notable places. It was also my introduction to a lot of amazing writers, including Lynne Tillman. This review originally appeared in the Washington Post Book World, then, as is the nature of these things, it more or less disappeared. Kirkus Reviews called the book “Beach reading for the John Hawkes set.” Which is pretty funny actually, stupid and smarmy and quite smart all at once. Would that all readers were of “the John Hawkes set.” The novel was originally published by Simon & Schuster’s Poseidon Press and finally reprinted by Red Lemonade. We have published a story by Tillman on Numéro Cinq. You can read it here.

Cast in Doubt

By Lynne Tillman

.

Cast in Doubt is a clever, witty, passionately written act of postmodern literary prestidigitation — a mystery novel without a body, a murder, or crime of any kind.

Not only that, but the novel’s hero-narrator, significantly a writer of detective mysteries, temporizes, delays, makes false starts and detours, searching for clues in old books, then completely muffs his investigative quest, and finally abandons it without solution.

Yet Lynne Tillman, the author of four previous books, writes with such elan, such spirited delight and comic intelligence, that it is difficult to take anything but pleasure in the jokes, aphorisms, potted etymologies and digressions which are the real substance of this book.

Tillman’s point is that the traditional mystery novel is an old-fashioned rationalist project, offspring of an outmoded epistemology. The crime is always soluble, the resolution a neatly logical tying up of motives and loose ends. A postmodern mystery novel, on the other hand, is about what Ludwig Wittgenstein called the “dark background” of our thoughts and words. As Horace, Tillman’s sixtyish, gay narrator says, “I am drawn to the mystery and inconclusiveness of life…”

Cast in Doubt begins on Crete, in a fishing village where a gossipy community of artsy expatriates dwells in restive seclusion. Horace, a New Englander by birth, lives with a Greek boy named Yannis and bickers fitfully with his fellow denizens — an insane South African poet, a former child movie star turned into a hermit who worships electricity, and a retired opera diva.

Helen, an American girl with a pierced nose, arrives one day to disrupt Horace’s complacency. Helen is beautiful and aloof. She carries a diary with “analyst” printed on its cover. In her wake trails a would-be lover named John who promptly attempts suicide by cutting his own throat. Like language itself, she seems pregnant with meaning.

Horace befriends Helen, toys with the idea of falling in love with her (as bizarre as this seems, even to him), then offends her with his nosy intrusiveness when he goes to visit John in the local hospital. As suddenly as she appeared, Helen departs, possibly in search of a mysterious Gypsy woman she has mentioned meeting.

Horace suspects Helen needs saving from something — her past (John mentions a twin sister who may have killed herself), or Gypsy con artists. He decides to search for her but falls under a spell of doubt and lethargy upon the arrival of his friend, Gwen, from New York. Gwen is a hip, cynical black woman, a famous scene-maker in the Village. She deflates Horace’s odd passion for the slender Helen, then makes a pass at the recovering John.

Eventually Horace does drive off, secretly, and in the wrong direction. He meets a Gypsy caravan, gets drunk, stays the night and has his fortune told — “You can’t see,” the fortuneteller intones. “You do not learn. You only look for the right things.” The next day, on a beach, he meets Stephen, the child-star-hermit, who happens to be carrying Helen’s diary, which Horace steals. Having found her private narrative, the story of the story, he loses interest in Helen herself and races home again. But the diary is enigmatic and fragmentary. It ends with a list:

Do laundry

buy glue

meet S

phone W

toilet paper

tampax.

Horace’s attempt to solve a real mystery, not just one in a book, comes to nought. Helen never reappears, nor is there any hint that anything untoward has befallen her. Years intervene — during which Horace writes a new crime novel appropriately entitled The Big Nothing. At the book’s close, he is bemused, philosophical, and contemplating a trip to the market.

Cast in Doubt is about meaning and the writing of books — and the impossibility of both. (Horace is always planning a magnum opus called Household Gods which never gets finished.) It takes language, not as a device for communication, but as a limiting concept characterized by what the post-mods call slippage (puns, double entendres, Freudian slips, etc.).

It says that things are not what they seem, that life is wayward and uncertain, and that there is high comedy in the collision between our over-weaning confidence in words and life’s mocking inconclusiveness. And when, as happens, Horace gets drunk and begins to vamp and dance, he becomes for us a precious image of all humans, not as wounded and alienated, but as fumbling, playful beings, essentially at home in and absorbed by the shifting messages and meanings that make up the world.

—Douglas Glover

(Originally published in Washington Post Book World, 1992)

.

.