Here’s a review I wrote nearly 20 years ago, published in the Chicago Tribune at the time. Efforts at Truth deserves to be remembered and reread, as does its author. God loves the outliers and eccentrics, his hopeful monsters, too.

dg

/

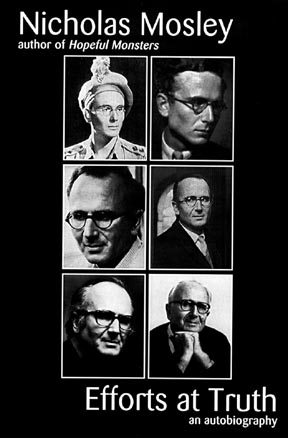

Efforts at Truth: an autobiography

By Nicholas Mosley

Dalkey Archive Press 1995

Nicholas Mosley is a rare beast — a reactionary revolutionist, what they call in Canada a Red Tory. He is an English lord, son of an infamous fascist anti-semite, a one-time Church of England apologist, and a writer for decades of highly regarded experimental novels in which he explores the ideas of consciousness and responsibility as a way of critiquing what he sees as the victim ethic of liberal modernity.

At first glance, he looks post-modern or avant garde, but he is not. He is just the opposite — pre-modern, if you will, the voice of an older tradition. Mosley is the champion of an heroic Christianity which reflates the Kierkegaardian ideas of paradox and the romance of risk. Not for him the Christian Coalition brand of weak religiosity with its emphasis on being saved — God’s version of Social Security.

Mosley places humans in the center of a mystery, with a duty to spend their lives paying attention, learning, experimenting — their reward being not safety but the chance of discerning a pattern. “To discover what is hidden,” he writes, “you have to go on a journey; what uproar, indeed, before you arrive at what is there!”

The author of thirteen novels and numerous works of non-fiction, family memoirs and screenplays, Mosley is best known in this country for his novel HOPEFUL MONSTERS which won the 1990 Whitbread Award in Britain and capped a brilliant sequence of books collectively called CATASTROPHE PRACTICE begun in the 1970s.

In CATASTROPHE PRACTICE, the same six characters weave through a series of stories dealing with contemporary issues of love, marriage and the upheavals of history. The books are difficult and unfashionably didactic — demonstrations of the paradoxical questing Mosley posits at the center of existence. But they are also immensely interesting, dense with a sardonic self-honesty, humane and accepting.

Now Mosley has written EFFORTS AT TRUTH, a magnificently idiosyncratic autobiography, in which, with characteristic tenacity, intelligence and decency, he tries to picture the patterns that have informed his own life and work.

Sir Oswald Mosley, the author’s father, was the dashing, charismatic, philandering leader of the Black Shirts, British Fascist sympathizers during World War II. Faced with the paradox of loving his father and hating his ideas, Mosley quickly learned to walk a tightrope between admiration and criticism. While his father languished in a British prison, Nicholas Mosley was in the army fighting Hitler. And amidst the fighting, he found time to exchange loving, deeply intelligent letters with his father.

This ability to hold contradictions suspended in thought, to walk psychic tightropes (Keat’s called it Negative Capability), with minefields on either side, is one-half of the Nicholas Mosley equation.

The other half has to do with the Bible, the Church of England and old-fashioned goodness. Mosley’s dissatisfaction with the traditional novel form stems from a commitment to a literal Christianity, the kind that explores earnestly what is meant by goodness, God and grace in worldly and up-to-date terms. Mosley is no born-again tub-thumper — he is the sort of Christian writer who can write, in his inimitably droll fashion, “For the experience of making patterns the word ‘God’ is useful, but not imperative.”

According to Mosley, modern novels portray characters as victims, with no room for assigning or accepting responsibility for actions. “The literary world seemed to have been taken over by a vast army of contemporary fashion in which freedom was denied and ideas of dignity and redemption mocked.” He set out to write books which, in his words, related the inner (thought) to the outer (actions).

This was no easy task. A new form had to be invented. Mosley’s prose style has a functional awkwardness built in (Mosley himself has always stuttered — he speculates upon the relationship between trying to see the world clearly and his inability to speak). He mixes together letters from lovers, wives and friends, excerpts from his essays and biographies, and passages that are formal pastiches from his novels.

One of Mosley’s favorite devices is the rhetorical question, which gives the narrative a questing quality, an open-endedness. Frequently, his syntax stretches for a kind hypothetical uncertainty — “And at the center of the paradox, should it not indeed be something about sponteneity that is learned?” Sentences like this read strangely at first, till the reader begins to see them as tied perfectly to the author’s project: the careful dissection of thought and action in an effort to reveal some central pattern whose nature may be inexpressible in ordinary expository terms.

Mosley’s rhetoric, like that of Jacques Derrida or Ludwig Wittgenstein, has the quality of seeming to teeter at the very edge of language. Those questions, the sudden twists of self-doubt, the leaps of understanding, the conditional hypotheses — have the effect of drawing the reader’s attention to something that is not quite being said or understood.

EFFORTS AT TRUTH weaves back and forth between Mosley’s life and the life of his books, showing how the one influenced the other. The discovery that, in his earlier books, he has repeated the self-sacrificial hero motif, leads him to shake off a post-combat depression and locate an unexamined yen for the Church of England. (What, after all, is Jesus but a self-sacrificial hero?)

He befriends a monk, suspends his novel-writing and takes over an Anglican magazine called PRISM from which pulpit he blasts the church for moral complacency. This wild turn into Anglicanism happens just as the Angry Young Men, writers like John Osbourne and Kingsly Amis, are storming the bastions of English letters and is an example of Mosley’s sturdy inability to stay with the crowd. Modishness is a vice to which he seems singularly, and sometimes comically, immune.

Meanwhile, Mosley has married, had children, and become willful philandering skunk like his father. At one point, father and son meet accidentally while chasing women in the same London dive. But Mosley’s monk-friend takes him aside and gently suggests there is something wrong in his family dynamic, especially in regard to children.

Till then Mosely has taken forgranted the upper class English notion that children should be raised by someone else. Author and wife energetically fire their nanny and begin to teach themselves how to take care of children, how to love them. Later on, he even figures out about the philandering mess — but not before his willfulness has ruined his first marriage.

Mosley has a fling with screen-writing when two of his novels sell to the movies. He suffers a terrible car accident from which it takes him a year to recover. He goes into analysis and marries a fellow analysand, both of them embarking on this venture in the charmingly naive belief that they have achieved wisdom enough to assure a problem-free marriage. “Here were Verity and I intending to be model spouses and parents in some psychoanalytically re-cycled Garden of Eden. Oh dear!”

Mosley is unsparing of himself, exploring his own smokescreens and cruelties, detailing the awful consequences of his infidelities. One woman has a nervous breakdown, another an abortion. In a letter, his first wife writes: “We are beastly when we are together, but I like you when you’re away very much.” One gets the impression of a creative volcano, an immensely intelligent and self-willed personality, guaranteed to give a rough ride to whoever comes within reach.

EFFORTS AT TRUTH does not set out to be a popular autobiography. There is no name-dropping, little inter-twining of current events (surprising for an author who, in HOPEFUL LOSERS, wrote a masterful historical novel). Mosley sticks with his work and his family, knowing that within this narrow ambit most of the great mysteries of life are played out.

All this is told with infectious brio. Despite the in-built difficulty of the argument, EFFORTS AT TRUTH radiates a cheerfulness, a curiosity about life that is fundamentally healthy and humane. Mosely marks his sins but does not compound them by wallowing in guilt; he does not present himself as a victim of his own faults.

EFFORTS AT TRUTH is an antidote for those who feel the current debates between the right and the left, the Moral Majority and the advocates of a social safety net, have bogged down in stale rhetoric and endlessly circling arguments. It is a brilliant work of literary artistry and an act of faith — a message of mysterious complexity that goes straight to the heart of existence.

—Douglas Glover

/

/

/