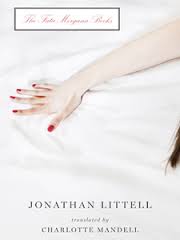

The Fata Morgana Books

Jonathan Littell

Translated by Charlotte Mandell

Two Lines Press

208 pp., $10.46

A Fata Morgana is a mirage visible just above the horizon line. The name is a hybrid term, with the Latin word for “fairy” combined with a reference to Morgan le Fay, the sinister witch from the legends of King Arthur. It makes sense: These optical illusions could easily be mistaken for sorcery, as light refraction distorts the image of a ship or an island from just beyond the horizon line, piling doubles and doppelgangers on top of each other, stretching or compressing them until they become almost unrecognizable.

Fata Morgana is also the name of the French publisher who brought out the original edition of Jonathan Littell’s new book of novellas, called in English The Fata Morgana Books, apparently as gesture of respect to the house that first issued them. If so, the coincidence is as surreal and bizarre as the stories in this strange short book, which rise like the faux castles and continents that baffled sailors in the Straits of Messina four hundred years ago, shimmering inexplicably at the far edge of the visible world.

Those who come to these tales expecting the standard protocols of narrative fiction, perhaps having just finished The Kindly Ones (Les Bienveillantes), Littell’s perverse epic Nazi confessional masterpiece (and winner of the Prix Goncourt in 2006), will find themselves adapting to a very different type of fiction. If as Umberto Eco suggests, any text molds its “model reader,” recalibrating the expectations of the audience from the first sentences, then Littell makes you over into a sensual voyeur of cryptic often displaced, deferred or interrupted erotic events unfolding among lovely but anonymous people who for all their couplings remain distant and alone.

“Études,” the first of the four novellas that make up the book, is itself written in four parts, or études, and describes the sporadic romance between the writer and B., his girlfriend. In the section called “A summer Sunday,” they are stuck with a group of friends in a city emptied by the war raging nearby. The writer longs for B., contemplates kissing her, but fails to act, “crucified by desire and fear.” Later he chides himself for obsessing over the incident: “You should learn to grow yourself a skin before you play at scraping it with a razor of such poor quality.”

In “The Wait,” the writer returns to Paris, the only named city in all of the interlocking stories, and waits – for a government posting, for word from the writer, for his life to begin. He entertains himself with a brief homosexual fling and then subsides into a waking coma of impatience and dissatisfaction.

As “Between Planes,” the third étude, begins, the war is back on center stage, disrupting civilian life without ever coming into focus. We read about “rioters” passing by in “commandeered trucks, waving green branches and chanting slogans against the new authorities,” whoever they may be. The narrator has a new girlfriend, C. who is traveling between an alphabet soup of anonymous cities, G____, K____ and M____ on various military transport planes, somehow never quite available for a meeting.

On one occasion the writer scores a job moving freight from the city, allowing him a layover with C. But a set of Kafka-esque bureaucratic entanglements, never described in detail, leave him standing on the tarmac, refused boarding privileges, clutching a yellow flower his hand. The situation is muddled, but the image lingers in the mind. The relationship with C. stutters forward, with shared insomnia and occasional revelations (she has a child, for instance, whom she had never mentioned and whom we never see). The writer never gets a clear view of her and neither does the reader; only the writer’s emotions remain clear. He is “distraught” at her aloof demeanor, “Mad with suffering,” but always “something very strong prevented me from pushing, from provoking her to a rejection that would at least have the merit of being clear.”

Littell salts these elusive events with striking images that shine brightly for a moment, revealing their emotional truth, car headlights glinting off the reflectors that mark a sharp curve on a dark road.

I was sitting in the lobby of the office where she was with the administrator when a little black and white bird flew in. It began walking around with disjointed but calm little steps, surprised at the closed door. Then it turned on a little moth that was sleeping there and attacked it with its beak. The moth struggled, but in vain and the bird swallowed it in a cloud of scales, a fine white dust of torn-off wings forming a luminous halo around its head.

This moment seems to define the power relationships in the entire story, both political and personal. At the end we are left with one more rejection and another cancelled flight.

The fourth étude, “Fait Accompli,” the most impressive text in the entire collection, features a leap into third person and an attempt at pure emotional abstraction. We have two characters – unnamed, of course, undescribed, virtually undifferentiated – thinking about the process of thinking about each other. Are these two people the characters from the earlier études? It must be, but it’s hard to be sure, because we have plunged from a satellite view of their actions to a close-up so extreme that we’re studying the pores on their faces, unable to see the larger features. This works because of the repetition of certain phrases, the obsessive recycling of language that perfectly captures to futile spin of the mind coping with jealousy and rejection. The narrative is abstract the way ballet is abstract. It’s a a dance of despair. The reader provides the music:

For him then, two questions, that is question 1 the other or not the other, and question 2 her or not her, To these two questions four solutions, that is solution 1 him without her without the other, solution 2 him with her without the other, solution 3 him without her with the other, solution 4 him with her with the other. Now for him at this stage with the other out of the question and hence out of the question solutions 3 and 4, remain numbers I and 2, without the other or without her, hence why not with, it wasn’t so bad, and it would be almost like before, except that in the meantime there would have been that. But here precisely is the problem, since for him with the other out of the question, for her without the other out of the question, of this he is certain, even without asking her I mean. So if for her, without the other out of the question, then out of the question solutions 1 and 2, remain thus numbers 3 and 4, already out of the question. So start again.

And he does.

The lover imagines various scenes with various settings – a Moscow subway station, a park at night, a restaurant, scenes with them walking or sitting, talking or silent or just exchanging letters, the phrases recurring — “the cage the locked window the key thrown in the pond”; “eating your cake and having it too” — the options divided by the chanted “or else.” Or else, or else, or else, with no solution, no conclusion, just an unfiltered, eventually unpunctuated down-spiral of despair with an unnerving intimation of violence: “Love in the garbage can, blood everywhere,” and the sudden possibility that all the time he has talking about not another lover but a child, not a three-way affair but a family, not a break up but an abortion. So the story becomes not simply the wild gyrating thoughts of a lover trapped by circumstance, but a plea for mercy. One can only hope that the woman will take his advice have the child, live happily ever, eat her cake and have it too.

But the chances are slim.

The remaining novellas feel connected, and Littell clarifies their subject, theme and purpose early in the first one, “Story about Nothing”:

…I didn’t really know if I was driving, or if, stretched out in this vast heat on the sheetless rectangle of my mattress, I was dreaming that I was driving, or even if I was having this sleeping-driver dream in the midst of driving, my hands inert on the black leather hoop of the steering wheel. Sleeping, I said to myself: one should write about this and nothing else, not about people, not about me, not about absence or about presence, not about life or about death, not about things seen or heard, not about love, not about time. Already it had taken shape.

We watch while it happens. The narrative devolves into reverie. The narrator drives to the beach, swims far out to sea, hears a woman’s voice calling him back – but from the dream of swimming not the swim itself; but the woman is only another dream, one more fata morgana mirage piling up on the horizon line.

He visits a friend’s house and the first thing he sees is a mirror, which will become the defining image for the remainder of this story and the final texts in the collection, “In Quarters” and “An Old Story.” Mirrors proliferate, cracked mirrors that evoke vaginas, black mirrors that threaten to swallow the narrator, mirrors on every wall and above every bed, reflecting every sexual act. And the sexual acts proliferate, to the edge of pornography, ever more perverse, from simple adultery to cross-dressing and three-ways and orgies.

At one point, the narrator is the only male at a lesbian pool party, though he’s dressed as a woman and many of the other woman seem to be hermaphrodites. Consciousness refracted through this hormonal haze creates its own stacked mirages: at one point he watches a porn film under a mirror that watches him watching the actors and seems to watch us watching all of them. You reel, amused, appalled, dizzy, from one surreal incident to the next. The narrator attends bull fights, nibbles lime sorbet beside swimming pools, enjoys affairs with interchangeable lovers, and somehow in the rush of action and memory, images or insights glint:

I had never received anything from her, either good or bad, she had never granted me any rights or down me any wrongs; what she had given me she had given freely, just as she had taken it back from me, and there was nothing to say to that, even though I was burning from head to foot in a fire of ice that left no ash. At the same time, I couldn’t have cared less about her.

Who is she? It doesn’t matter. The dream is moving on, in this case into the next novella, “In Quarters,” which amplifies and deepens the dream imagery, with an even more delicate filament of reality holding the scenes together. The story starts and ends in a large communal house with the narrator surrounded by busy adults and swarms of children, none of whom seem to notice him. One of the children, a blond boy who keeps turning up, may or may not be the narrator’s biological child.

Eventually he leaves this exclusionary idyll and returns to his own apartment, shadowed by mysterious men in black overcoats, a sinister surveillance that contrasts sharply with the way he moves through the big house like a ghost. He meets a woman at his apartment, they have sex, examine brutal war photographs, and before we can discern what their actual relationship might be, he’s on a train. It arrives at the destination and we watch the dreamer wandering around the town, looking for his friends, amid a tense atmosphere of unspecified political unrest.

Soldiers, overheard ominously talking about some faction “going too far” and “provoking” us, recall the early sections of the first novella “Études,” — the characters enjoying an eerie holiday atmosphere of a town cut off by war. And everywhere, shapes float on other shapes, pools against lawns, coverlets on beds, even the Rothko like squares in a painting that seems to watch the author as he moves around the room, evoking mirrors. Then the narrator finds some handwritten pages, a story in his own hand, which he doesn’t recognize, though it describes the events that began this narrative: wandering unseen through the densely populated mansion. “In any case it has nothing to do with me.”

The reflections and mirages continue to pile up. Eventually he returns to the mansion to find that the blond boy who might be his son has fallen ill. He sits by the boy’s bedside. “He raised his hand and placed it over my own, it was light as a cat’s paw, dry and burning.”

Everyone else still ignores the narrator — except the doctor, who eventually pays a house call. When he walks the doctor to his car in the street outside the mansion, the men in black close in, presumably to arrest him. For what crime? We can only hope he’ll awaken before he finds out.

And then we come to “An Old Story,” the final novella, which begins and ends with a man breaking the surface of a swimming pool from below, stroking up into the recycled air of the health club, or mansion basement, or prison exercise area, or … well, in fact the location of the pool doesn’t really matter. It’s too deeply buried in the unconscious mind of the narrator to need a geographical tag. By now it’s a familiar spot anyway, filled with strangers, surrounded by mirrors, the gateway to another cycle of dreams.

In this case the circular nature of the sequences become explicit. The narrator dons a track suit and starts jogging along a circular corridor, opening various doors, going inside for a surreal experience, then leaving and jogging on. In the first room he seems to be married, with a son much like the one in the previous story. There are problems with the electrical service, another theme that will recur through all the following vignettes, along with the plaintive excuse that the narrator called the electrician twice to have all the wiring overhauled. There are paintings that seem to observe the action and mirrors that reflect them, and a sense of menace and war in the background, and sex, always plenty of sex. In this case the child catches the narrator and the woman in the act. He runs off and the woman goes to find him. Night has turned to day, and the narrator steps outside into a lovely garden, feeling “a strong morning heat that clung to the skin.” Once again, a crystalline, perfectly observed image anchors the floating world for us.

Soon the narrator is running along the corridor again. Soon he finds another room, with another bed and another woman and another set of mirrors, the bed like all of them covered in “a heavy golden cloth, embroidered with long green grass” that evokes the chaise lounge on the lush lawn of a previous story. Here windows facing into the night (it’s night again) take on the looking-glass chores. And the sex grows funkier, with the woman using a dildo on the narrator in a prolonged scene rescued from the prurient and the salacious by the eerie detachment of the narrator himself.

He wakes up into another dream, another room, another bed with the same coverlet, and another woman, Here again the exotic raunch, escalates, with the narrator cross dressing and finding himself attending the lesbian pool party mentioned earlier. The pool itself functions as another mirror. And it goes on: he becomes by turns a child slave, the murderer victor in a conflict with a gay male prostitute, a voyeur, a sex-starved scavenger roams a surreal gay bathhouse, once again caught by the child in an even more compromising position and finally the leader of some barbaric Medieval army engaged in a war vague enough to echo the peripheral battles that began the collection. The woman in this story he rapes and murders, as the increasing perversity of these linked dreams starts to spiral out of control.

Then, when it seems like nothing more could possibly happen, the narrator is emerging from the water, breaking the surface of the pool, back where he started, at the beginning of the novella, and seemingly cued up to begin again, launched into a sequence of dreams perpetually eating its own tail, a nightmare of recurrence from which he can never wake up.

Littell’s message remains constant in these shifting tableaux: life may be largely meaningless, but is nevertheless redeemed by isolated moments of pure beauty We are hopelessly self-conscious, yet tragically incapable of real self-awareness, doomed to repeat both our pleasures and our mistakes until we learn to distinguish between them.

It’s a gorgeous tour through a world of human excess and futility, exhilarating and exhausting, a world, yes, ruled by repetition, doubling and displacement, a world in which the mind cannot escape the mind. After a couple of hundred pages squinting at the fabulous fata morganas of a refracted continent, I longed to make landfall and feel the actual sand between my toes. But I suspect that was at least part of Littell’s intent. Like many deep water ocean voyages, this one had passages of fear and boredom, but also exalted spikes of strangeness and beauty you could never encounter closer to shore.

—Steven Axelrod

———————————————–

Steven Axelrod holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of the Fine Arts and remains a member of the Writers Guild of America (west), though he hasn’t worked in Hollywood for several years. Poisoned Pen Press will be kicking off his Henry Kennis Nantucket mystery series in January, with Nantucket Sawbuck. The second installment, Nantucket Five-Spot, is scheduled for 2015. He’s also publishing his dark noir thriller Heat of the Moment next year with Gutter Books. Two excerpts from that novel have appeared in the most recent issues of “BigPulp” and “PulpModern” magazines. Steven’s work can be also be found on line at TheGoodmenProject and Salon.com. A father of two, he lives on Nantucket Island where he writes novels and paints houses, often at the same time, much to the annoyance of his customers. His web site is here.

A fascinating review of a piece that seems to be brimming with the stuff of real dreams, dreams which carry echoes of a mysterious reality that marks their presence by roiled events only distantly related to actuality, like the violent waves and splashes of the surface of the sea under which anonymous monstrous creatures struggle but never reveal themselves. Words have an arcane power far more potent than the images that film and other visual arts barely touch and this writing seems well worth the experiences offered.