Today is the Russian Orthodox Feast of Transfiguration, also Hiroshima Day, a day of near absolute contradiction. Hilary Mullins takes the opportunity to explore the person and teaching practice of the late Don Sheehan, whose spirituality (Russian Orthodox) and spirit made him perhaps one of the most remarkable writing teachers ever. Part portrait of the man, almost a hagiography (an ancient genre, not to be dismissed), part exploration of what a writing workshop might be if suffused with spirit, part exploration of technique (chiasmus, a little form, strewn through the Bible), part homage, part homily, Hilary’s essay crosses genres and practice in a remarkable and loving way.

dg

—

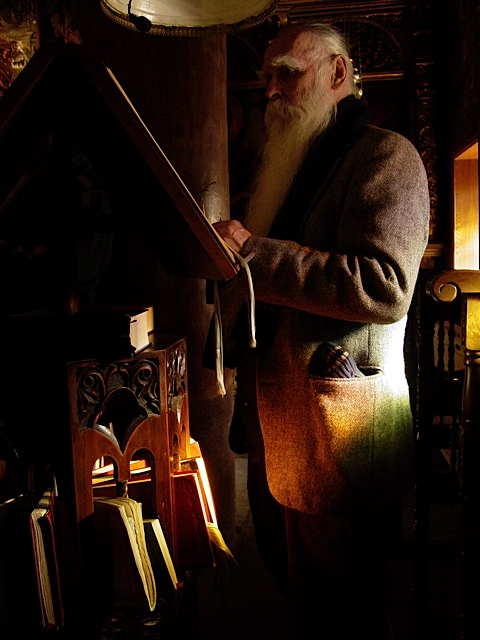

Nine a.m. August 6th 2004, and at The Frost Place in Franconia, New Hampshire, we are assembled in Robert Frost’s old barn. It’s the second-to-last day of the annual week-long poetry conference, and though lots of us are tired at this point, there’s still a quietly-bright buzz in the air: every day here brings good things. But before the morning’s lecture gets underway, Don Sheehan, founding director of The Frost Place, rises and walks to the lectern, clearing his throat to make his customary morning remarks.

At this point, Don, with the quiet assistance of his wife Carol, has been running The Frost Place for almost thirty years, handling the multitude of various tasks involved. But I know very little about all that: the thing I have been learning about Don Sheehan is how, through all his teaching, he helps people bring forth their best and deepest selves and change their lives.

This morning he begins by noting the date: August 6th, going on to explain how it is one of the high holy days in the Russian Orthodox calendar, the feast of Transfiguration. This of course is not a common topic at most writing workshops, but his Russian Orthodox faith is a common topic for Don, and he begins to elaborate on the biblical story, describing how Jesus, taking three of his disciples, climbs a high mountain where suddenly he is transfigured by light, his face shining like the sun, his clothes dazzling white. The wonderful thing about this, Don stresses, is that this moment of Jesus’ transfiguration is also a transfiguration of the world: the holy is here. Not somewhere else, but here, now.

•

Nine years it’s been since Don spoke those words and he himself now is no longer here.

And yet, I think of him almost every day. And looking back, part of what strikes me is how truly unusual he was, not only in the largely secular world of writing workshops but probably in most places he went. At the most obvious level, the reason for this was his devout Russian Orthodox practice. But it went far deeper than that, as did his gifts to those of us who knew him.

Though I am a Unitarian Universalist myself, I had the great fortune to know him first in his own context, tagging along with a friend one evening to what I thought was a Bible study class for members of St. Jacob’s, a small Russian Orthodox congregation in Northfield, Vermont. What I was expecting was a small circle, primarily women, gathered around the priest in chairs, nibbling cookies perhaps, leafing through Bibles balanced on their knees, commenting perceptively but mildly on lectionary passages.

What I got was something altogether different. For one thing, the people who came to the class that evening, men and women both around the table, were serious in a way I was not used to. That was partly a function I’d guess of the devotional character of Russian Orthodoxy, with its calendar structuring life around faith. But it was also Don himself. A scholar with a poet’s heart dedicating the bulk of his energies to the Russian Orthodox tradition, he taught by spreading out the fruits of his scholarship and inviting us to take and eat. My own beliefs, theologically speaking, run along more liberal lines than his did, but I knew right away on that first night in his class, he was the religious teacher I’d prayed to find. So I kept attending and sometimes too visited him and Carol in Sharon at their home, sharing meals, spending time in the garden and, wonderful pleasure, spending time also with the rest of their family.

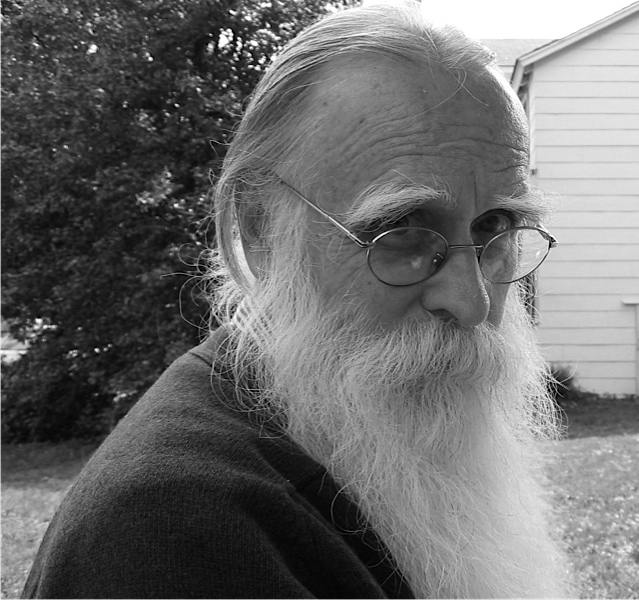

Even then, Don was already ill, suffering with the beginning symptoms of the condition that three years ago ended his life, probably an undiagnosed case of Lyme Disease. And yet though I remember him being bone-tired, he never lost his gentleness or his characteristic bright clarity. He was in his mid-sixties then, with fly-away eyebrows and look-clear-at-you blue eyes–a shy, soft-spoken man, reflexively self-effacing, who appeared like the scholar he was in his well-used, rumpled khakis and button-up shirts–except that because he and Carol were off the grid on their somewhat remote hillside in the woods, he also wore things like serious boots in the winter and a faded blue hand-knit hat to keep away the cold.

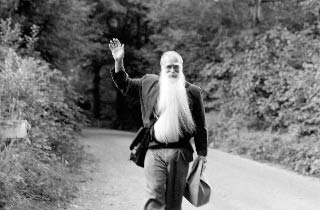

And that is another key thing to understand about Don: money and position were never his goals. This is clear for instance, in the decision he’d made much earlier in his life, before his conversion, to give up a tenure track job at the University of Chicago. In fact, even though he was at Dartmouth, Don Sheehan was an adjunct professor—a low-rung position on the academic ladder. But I doubt he regretted his choices–not because he lacked ambition, but because his ambition aimed for what he thought were worthier things. And this dedication of his to higher callings had a tendency to rub off on others. For Don Sheehan had a way. He was never one to call attention to himself, but in a room full of people, he was still someone you’d notice, not least of all because of his unusually long beard, the kind older Russian Orthodox men seem to cultivate. It draped down over his chest, a fluffy white wing attached to his chin.

I don’t mean to claim by this Don was angelic exactly, but the truth is, the man was so immersed in soul-work, he threw off a little light. And he was always casting that light toward you. That was one of the remarkable things about him: given his teaching at the church, and at Dartmouth, and particularly as director of The Frost Place, he was continually in situations perfectly rigged with opportunities for misusing his power and padding his ego. But he passed all that by, leading in the humblest way I’ve ever seen. And I don’t think this was because he failed to understand power: I think it was because as a man and as a Christian, he understood the best thing to do with power is give it away. Not to dissipate it, as if it were a dangerous electrical charge, but to transform it into love, keeping the circles of its impact ever rippling out into the world at large.

Another element fundamental to this practice of self-extending was the way Don did not strike. Having survived a childhood that was at times shattered by brutal violence, he understood the multitude of diverse, often subtle blows we deal one another. And he made a practice of not passing them on. So, in class at St. Jacob’s for instance, he never engaged in the far-too-common disheartening practice of chopping up or dismissing our responses. There were even times when I wished he would—a little anyway—be a tad more corrective perhaps—for instance, when it seemed another student’s reading of a passage was clearly off the mark. But it was Don’s habit instead to say yes and keep us walking with him, all the while modeling the way through his own fine work–essays and lectures that were deep and wide and reflective, pathways into marvelous complexities.

This approach of his he made explicit in The Frost Place workshops, starting off the week each year with these words:

“If you must make a flash choice between sympathy and intelligence, choose sympathy. Usually these fall apart—sympathy becoming a mindless ‘being nice’ to everyone, while intelligence becomes an exercise in contempt. But here’s the great fact of this Festival: as you come to care about another person’s art (and not your own), then your own art becomes mysteriously better.”

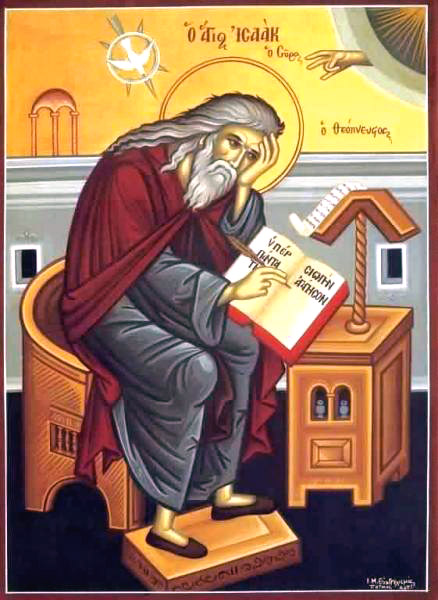

And it was true. We were all always becoming mysteriously better under Don’s tutelage. And happily, he had a way of making the work itself deeply satisfying, approaching writing not only as a believer but a lover too. In our classes at church for example, passages from the monastic Saint Isaac of Syria or the chapters in 1st and 2nd Samuel were not abstract ‘texts’ to be deconstructed: Don was no vivisectionist. Instead, he turned all the powers of his scholarship towards bringing out a passage’s depth, approaching each one as real, as a lovely, created thing, like a chapel or a shaded pool, a place to be entered with reverence and wonder and pleasure.

Likewise, it seems to me that what Don did at The Frost Place was very similar, renewing poetry for others because he believed it too was real. And this is not just a pretty way of speaking. Where our secular culture denudes the sacred properties of poetry, of all art in fact, Don was deeply grounded in a tradition that has never lost its sense of the holy in art. As I understand it for instance, a Russian Orthodox icon, properly prepared and painted, is not just a painting: it is a portal for the holy, an actual opening through which God moves toward us and through which we can move toward God, where indeed we are invited to do so.

The same goes for the written word: just as St. Isaac of Syria had explained in the 7th century, holy books in Russian Orthodoxy are understood to be places where the light of God shines through: “Those who in their way of life are led by divine grace to be enlightened are always aware of something like a noetic ray running between the written lines which enables the mind to distinguish words spoken simply from those spoken with great meaning for the soul’s enlightenment.”

The first time I read those words off a Xeroxed sheet in Don’s classroom, they made the lights come on in me, as if a Christmas tree in a darkened room had just been plugged in, glowing suddenly with the light I’d always known was there in things I read and loved, bits of bright color weaving in and out of the branches, deep glimmerings from within all the recesses.

The psalms too, were places Don brought us into the same way, teaching us the ancient chiastic pattern they’re written in. That is to say, psalms move not only from start to finish in the linear way we’re used to, they also move in a call and response fashion across the whole of the psalm, back and forth across the center, calling us, as we read, to pay attention to how the first and last verses are related, along with how the second and second-to-last are connected too, and all the others in just the same way, until we reach mid-point, which is the place where, one way or another, God appears, turning the poem in some way. But of course for Don whose religious practice for years had included praying the psalms every day, this appearance of God wasn’t simply a reference that functioned in the narrative logic of the poem: it was, just as in icons, the place where touching and being touched by God was actually possible.

To us this chiastic doubling-back-and-forth pattern across the center is so counter-intuitive, it can take some getting used to, but one inexact analogy is this: think of yourself again as a child, hopping along a slate sidewalk, coming down from every hop with one foot on each of two paired slabs—hop, hop, hop–until then you come to the center, the deepest point of the journey, where the presence of God wells up like a sweet water spring in a hollow. Then imagine laying down, here, now, in this marvelously still, green-grass place.

Now you might think from these kinds of descriptions that what I’m going to relate next is the story of my own conversion. But that is not what happened: I was certainly changed by Don’s teaching, and I loved the way his tradition approached things that usually are understood as merely metaphorical, rendering them instead as vibrantly and powerfully real. But still, I have never shared his—or anyone else’s–certainty about the workings of the divine. And Don knew this. Yet, in spite of that deep commitment to his own faith, he never cajoled conversion or conversely set me outside the walls in any way: these too were the sorts of corrections he did not engage in. Even while we were studying Isaac’s lovely passage about the noetic ray glimmering in amongst the written word, and I said I’d experienced the same thing in, say, a poem by Frost, Don did not close the door. “Orthodoxy points to where the truth is,” he said. “It doesn’t say where the truth is not.”

It was this sort of catholic approach that meant poets even more secular than I could benefit from Don’s sense of the holy in poetry. We never talked about this explicitly, but my guess is that his daily contemplative reading of the psalms did lead him to find many contemporary poems to be empty, echoing forth a hollow space where he was accustomed to sensing God. And yet it seems he did sometimes see more in them too. For instance, once, on the wooded hill beside his house, I asked him, theologically speaking, for his definition of grace. He smiled in his unassuming way and told me he thought it was like the passage in Frost’s poem The Death of the Hired Hand, where the farmer and his wife, in the course of deciding whether or not to take in their occasional (and historically unreliable) hired man, are talking about the definition of home:

“Warren,” she said, “he has come home to die:

You needn’t be afraid he’ll leave you this time.”

“Home,” he mocked gently.

“Yes, what else but home?

It all depends on what you mean by home.

Of course he’s nothing to us, any more

Than was the hound that came a stranger to us

Out of the woods, worn out on the trail.”

“Home is the place where, when you have to go there,

They have to take you in.”

“I should have called it

Something you somehow haven’t to deserve.”

The last lines of course embody the generosity of Don Sheehan himself, a generosity he shared through all his teaching, be his subject a homily of St. Isaac’s, a poem of Robert Frost’s, or a theological concept he thought could bring something deeply good to our lives too. But he was remarkably kind in smaller, everyday acts as well, even in the very way he gave you all his attention in a conversation. And the sum total of all this of course is that this ongoing generosity of his quietly but powerfully influenced many, many people.

And because he knew the healing power this practice had for him as well, the mysterious way it had of making him better, he was always enjoining us to do the same: “Your work at this conference,” he would say at The Frost Place, “is to make the art of at least one other person better and stronger by giving—in love—all your art to them.”

In the end I think he stressed love so much because he knew and understood its opposite so well. He and I never discussed what went on in his home when he was a boy, but in an essay on the Orthodox concepts in The Brothers Karamazov (still easily found online), he referred to that history to make a point, writing, “I was raised in a violent home where, until I was nine years old, my father’s alcohol addiction fueled his open or just barely contained violence, a home where my mother was beaten over and over (I remember her face covered with blood).”

Nine years ago, on August 6th, 2004, when Don Sheehan got up before the morning’s craft lecture and spoke, of all things, the Transfiguration, of the miracle of the holy transfiguring the world, he turned next to its opposite, bringing our attention in his measured way to another event marked by August 6th: the bombing of Hiroshima: “This,” he said, “we can refer to as a disfiguration of the world.” Knowing disfiguration as he’d had in his own life, his phrasing was deliberate as quietly he urged us to choose transfiguration in our own lives, yielding not to the innumerable temptations to slight or demean others but instead to make the kinds of gestures that embody the practice of love.

This of course was how Don Sheehan himself transfigured the world as he traveled through it, bringing light wherever he went. And it was what he was pointing to again and again in everything he taught, just as he did each year at the beginning of The Frost Place Festival: “The key that unlocks all truth,” he said, is “taking very great and very deliberate care with each other.” This infinitely exacting, transforming task was his greatest lesson, the one that is up to us all to carry on.

— Hilary Mullins

Editor’s Note: Don Sheehan did finish his translation of the Psalms and the book will be published shortly by Wipf and Stock.

—————————

Hilary Mullins lives in Bethel, Vermont, teaching public speaking for Vermont Technical College and cleaning windows in the warmer months. She also does occasional preaching for local churches. Along with an MFA from Vermont College, her education includes classes at the UU’s Starr King School for the Ministry, as well as completion of a three-year study program run by the Vermont UCC.

.

.

.

.

.

This was lovely, Hilary. It deserves to be read again and again.

Thanks Richard! I felt the same way about your essay this issue on reverence–so often that’s what I’m looking for too, longing for that sense of connection with something larger, better, ineffable….

Thanks, Hilary, for this wonderful essay. I especially love the kinetic analogy for chiastic structure! Or maybe your friend’s inclusive interpretation of orthodoxy: where the truth can be found, but not where it can’t.

Thanks Maggie, and I’m glad you liked that bit of hopping! As for Don, yes, he was so generously inclusive that way–so welcome in a world that is often the opposite. He made distinctions without making divisions.

Hilary Mullins, what you say about Don Sheehan, that “he made distinctions without making divisions” is what I had the privilege to witness as well. Surely he practiced compassionate ways-of-being so that his heart informed his behavior and his behavior informed his heart. It is wonderment to me when a person’s persona, is transfigured into authentic personhood. Your article about Don Sheehan honored him so reverently.

Thank you!

Dear Hilary: beautiful! As someone who knew and loved Don, I can attest to the accuracy of your words. Thank you.

Thanks for your comment Mark. And thanks too for taking that wonderful photograph of Don–it really captures the warmth of his spirit!

I agree with Mark…Don (Orthodox Subdeacon Donat) is a special gem of the creation and redemption in Christ, whom he loved so passionately and faithfully. Don is an outstanding exemplar of Theosis as manifested in the Transfiguration. He Lives the Eternal Love-Life in Christ in the infinite embrace of the All Holy Trinity. I miss him quite a bit.

Subdeacon Paul, Orthodox Chaplain Emeritus, Dartmouth OCF

ST. SUBDEACON DONAT DONALD SHEEHAN IS ONE OF MY FAVORITE SAINTS IN HEAVEN. ST. DON PRAY TO CHRIST-GOD FOR US, THAT HE MAY SAVE OUR SOUL!

Wow, it is wonderful that this great man’s legacy can continue through Hilary’s writing.

Thanks Bill for your comment, and yes, it’s true! Don Sheehan was like you, always aiming to lift others up. You never can tell at the time how that kind of legacy will be carried on, but one way or another it always is…..

Thank you Hilary. I am Lee Browne in Missoula, MT, an old friend of Don and Carol, a former parishioner of Holy Resurrection Orthodox Church in Claremont, and a member of a long-ago poetry workshop at The Frost Place (1998, I believe). Your essay rings marvelous true. With love from Lee

Thank you Lee. It’s really nice to hear from friends of Don’s–connecting up the larger circle of love around him even now.

Dear Hilary Mullins, You write so elegantly of the gentle depth of Don Sheehan. The light he shared is present in you and in your writing. Truly your title conveys his blessedness. Thank you