All That Is

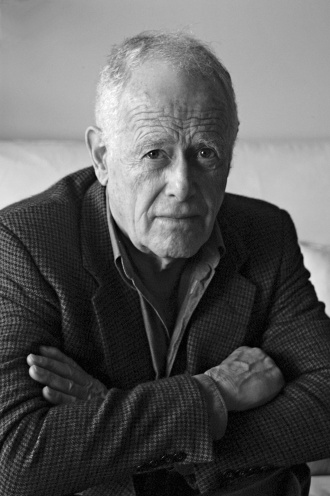

James Salter

Alfred A Knopf, 2013

290 pages, $26.95

In an age and a culture that have seemingly lost a sense of discrimination and taste, James Salter has once again elevated the American novel to a place of punctilious dignity, gimmick-free prose, and passionate sexuality. All That Is, Salter’s first novel in over thirty years, is an exquisite story of love, betrayal and humanity set against the backdrop of the New York publishing world.

All That Is chronicles the life of Philip Bowman, an editor at a small, literary publishing house. The novel opens in 1944 with Bowman standing watch on a warship crossing the Pacific. As sailors search the skies for signs of the dreaded Kamikaze, a young Bowman worries how he will respond in battle. “How he would behave in action was weighing on his mind that morning as they stood looking out at the mysterious, foreign sea and then at the sky that was already becoming brighter. Courage and fear and how you would act under fire were not among the things you talked about. You hoped, when the time came, that you would be able to do as expected.”

Salter is obsessed with rites of passage. Combat, sexual experience, home ownership, marriage, divorce, parental death and career success are among the many trials through which Bowman must pass. “What are the things that have mattered?” a woman asks Bowman at a London bar after the war, and this question might well form the narrative spine of the book. Is it a quest for a fulfilled life? Is it love, or the meaning behind love? Whatever the answer, we may rightly expect that many of the things that matter will be rendered.

After the war, Bowman returns to America, attends Harvard and eventually lands a job in New York. He meets his future wife, Vivian Amussen, in a bar, and soon woos her into bed. His first sexual encounter ends quickly, but he feels “intoxicated by a world that had suddenly opened wide to the greatest pleasure, pleasure beyond knowing.” Alas, the marriage is not meant to thrive. Vivian comes from a gentrified, Southern family and Bowman never quite fits in on the Amussen farm. There’s a brief period of somewhat muted happiness between the young couple, but on a business trip in Europe, Bowman has a passionate affair with Enid Armour. “It seemed his manhood had suddenly caught up with him, as if it had been waiting somewhere in the wings.” We aren’t surprised by any of this, of course, because his marriage seemed destined for trouble from the start.

Told in a kind of limited omniscience (anchored for the most part in Bowman’s perspective), the narrative bends the most important characters (and even some lesser characters) into the text with terse, jump-cut bursts of interior narration and point of view shifts. There’s something brash about this approach. It hearkens back to the nineteenth century when authors exercised complete authority over their creations. In a brief scene at Bowman’s wedding, Salter uses nine different points of view in just under three pages. The effect is appropriately dizzying, as though we are drunk and dancing at the reception.

Salter renders his secondary characters fully in quick, highly compressed flashes. For example, in the that wedding scene, he briefly cuts to Bowman’s mother, a woman whose presence heretofore has been muted:

“Be good to one another. Love one another,” she said.

Though she felt it was love cast into darkness. She had doubts that she would ever know her daughter-in-law. It seemed, on this bright day, that the greatest misfortune had come to pass. She had lost her son, not completely, but part of him was beyond her power to reclaim and now belonged to another, someone who hardly knew him. She thought of all that had gone before, the hopes and ambition, the years that had been filled, not just in retrospect, with such joy. She tried to be pleasant, to have them all like her and favor her son.

Notice the superlatives, the subdued hyperbole, the broad brushstrokes used to create a sense of time and history. The delivery is economical, a method prone to abuse by writers who don’t do the deep emotional thinking behind such narration. Salter refuses to fill in the blank spaces, but we feel them deeply, little resonant pools of mystery and being.

Bowman and Vivian break up, and he licks his wounds by briefly rekindling his affair with Enid in Spain. After the death of his mother, Bowman begins to stare down middle age, and becomes intent on finding a house in the country. There’s a certain disjointedness about the book’s pacing, and the reader must struggle a bit to assemble these moments into a coherent narrative. Then again, Salter has long been the master of minimalism and negative space. He manages to make vivid and vital characters, sometimes at the expense of plot. But a trust develops between the reader and the author, born of the latter’s wisdom and experience. We believe in the crafted dream, and don’t require much in the way of explanation. The gaps and questions are easily overlooked because Salter does the heavy filtering for us, removing the dross and delivering what he deems are the necessary parts, the distilled story, flowing in crisp sentences, swift and stripped-down scenes, strange juxtapositions, and whole characters rendered perfectly in only a few paragraphs. This is the quintessential Salter styling, and few do it better.

The third great love of Bowman’s life is Christine, a married woman trapped in a dead-end marriage. For awhile, she seems to be the perfect match. “He was free to do anything. It had never been this way, not with Vivian, certainly not with Vivian, and not with Enid.” Christine and Bowman eventually buy a home together, sharing it with Christine’s daughter, Anet. But again, for Bowman, this love will exact a heavy toll.

Salter, now 87, is a West Point graduate; he was fighter pilot in the Korean War. His first novel, The Hunters (1957), recounts some of what combat flying must have felt like. Several novels followed, including The Arm of Flesh (1961), A Sport and a Pastime (often considered his finest novel, 1967), Light Years (1975) and Solo Faces (1979); his short fiction was published in Dusk and Other Stories (1988) and Last Night (which includes one of my all-time favorite short stories, “My Lord You,” 2005). In addition to his fiction, Salter has written numerous screenplays, poems, travel essays, and even a literary cookbook of sorts, Life Is Meals: A Food Lover’s Book of Days, which he co-wrote with this wife. In 1997, he released Burning the Days, his captivating and powerful memoir.

Never one afraid to shove aside cultural sensibilities in search of a good story, Salter swipes at the social and historical changes which blew across America during the latter half of the twentieth century in All That Is. While not necessarily a critic of feminism, or liberalism or even of capitalism in general, Salter does critically examine the shifting effects of those movements on his subject, in this case, the middle-class, white, American male. In so doing, he offers an unsentimental, post-Empire look back on all that was Empire. The stultifying decadence of America after World War II stood in sharp contrast to the all-but destroyed, majestic cities of Europe (we visit a few in the book). But even unscathed, America was rife with problems below the glistening surface: prevalent racism, the objectification of women and the cracking structures of family. Salter seemingly wants to show us the dry rot in the clubhouse walls of white privilege and old-boys networks. The world is changing, but the Architects of Empire continue to sip their Scotch and sodas even as the clamor in the streets grows ever louder.

At first glance, many of Salter’s characters appear to typify the myth of the brusque, strong-shouldered American male. Yet Salter transcends this myth, taking aim at the American Dream and pulling the trigger. Bowman, in many ways, is a feckless hero. Love eludes him, but he carries on in spite of his setbacks and disappointments. Though a virgin when the novel opens, Bowman’s primary fault lines are sexual ones, and, for him, love and sexuality are inextricably linked. “It was love, the furnace into which everything was dropped.”

It’s hard not to think of Hemingway when you read Salter, except a less vainglorious version. Whereas Hemingway wants to drink you under the table and shut down the bar, Salter wants to order a bottle of Château Latour. They both want to seduce you, it’s just that Salter will still be upright and semi-sober when he does it, and he’ll buy your breakfast in the morning; Hemingway won’t even leave a note on the pillow.

And make no mistake, Salter likes to write about sex.

She lay face down and he knelt between her legs for what seemed a long time, then began to arrange them a little, unhurriedly, like setting up a tripod. In the early light she was without a flaw, her beautiful back, her hips’ roundness. She felt him slowly enter, she reached beneath, it was there, becoming part of her. The slow, profound rhythm began, hardly varying but as time passed somehow more and more intense. Outside the street was completely silent, in adjoining rooms people were asleep. She began to cry out. He was trying to slow himself, or prevent it and make it go on, but she was trembling like a tree about to fall, her cries were leaking beneath the door.

Notice how he leaves much to the reader’s imagination, and how the act and the emotion fail to fuse. Like life itself, love and sex are deeply sad and fleeting things. And this may indeed be Salter’s point, the emphasis falling on moments rather than on the prevalent myth of permanence. Words like eternal love and forever seem rather cloying and foolish when placed next to the reality of experience.

Love, finally, eludes Bowman. His affairs of the heart end badly. What makes Bowman empathetic and heroic is his refusal to be defeated. He remains stalwart and upbeat, even as setbacks befall him. He retains something of a quixotic delusion about love, but this makes his failures less pathetic and his forbearance admirable. By the close of the book, Bowman arrives at a certain wisdom, even if he must first pass through a stage of numbed-out cruelty. In the book’s most shocking reversal, Bowman executes a brutal, cringe-worthy, act of revenge-sex that creates a complex emotional space for the reader: you simultaneously root for and hate the hero.

Of course, Bowman is not heroic in a traditional sense. His trials are hardly the stuff of legend. He wins quiet victories, endures muted disasters, and carries on through authentically human struggles. Remember, he’s a book editor, itself a quiet job that hides in shadows. But there’s an abundance of dignity in Bowman’s life. He works hard at his job, maintains virtuous standards toward his work. A certain decorum surrounds his struggles and triumphs. There’s also nostalgia for now old-fashioned independent publishing houses like Braden & Baum. Parties, business trips, working dinners, talented authors and exotic women make Bowman’s world quite full, quite rich, by almost any standard.

The French writer Marguerite Duras wrote that “the person who writes books must always be enveloped by a separation from others.” With Salter, one might well suppose the opposite to be true. He seems to be a writer who has lived life fully even while writing many of the books that have helped define a culture. In a recent interview at Guernica, Salter was asked about immortality as a writer:

You would have to be very optimistic to think that any of your books will be among the books that survive in the very long run. I think if a writer is lucky enough to still have a few books around after he’s gone, a few that are still being read, then he’s accomplished quite a lot.

While Salter is correct about the uncertainty of predicting trends and tastes, few writers today are more deserving of a long literary legacy.

—Richard Farrell

—————————

Richard Farrell is the Creative Non-Fiction Editor at upstreet and a Senior Editor at Numéro Cinq (in fact, he is one of the original group of Vermont College of Fine Arts students who helped found the site). A graduate of the U.S. Naval Academy, he has worked as a high school teacher, a defense contractor, and as a Navy pilot. He is a graduate from the MFA in Writing Program at Vermont College of Fine Arts. He is currently at work on a collection of short stories. His work, including short stories, memoir, craft essays, interviews, and book reviews, has been published or is forthcoming at Hunger Mountain, upstreet, A Year in Ink Anthology, Descant, New Plains Review and Numéro Cinq. He lives in San Diego.