What ultimately matters is the magnitude of Knausgaard’s investment in his project, the sense that here is a man writing to save himself, writing to survive, writing because these things mean so much to him. Somehow, he is able to make them mean almost as much to us. Like all great art, whatever the genre, one leaves these books with a renewed feeling for what life and art can be.

—Eric Foley

My Struggle: Book Two

A Man in Love

Karl Ove Knausgaard

Translated from the Norwegian by Don Bartlett

Archipelago Books, trade cloth

576 pages, $26.00

A Story of the Struggle to Tell a Story

“Meaning requires content, content requires time, time requires resistance.”

—Karl Ove Knausgaard

The year is 2007. For the past four years, Karl Ove Knausgaard has been trying to write about his troubled relationship with his deceased father. Though the 38-year-old author has two previously acclaimed novels under his belt (Out of the World, 1998, and 2004’s A Time For Everything), this time around the attempt to cast his material into fiction isn’t working:

Wherever you turned you saw fiction. All these millions of paperbacks, hardbacks, DVDs and TV series, they were all about made-up people in a made-up, though realistic, world. And news in the press, TV news and radio news had exactly the same format, documentaries had the same format, they were also stories, and it made no difference whether what they told had actually happened or not. It was a crisis, I felt it in every fiber of my body, something saturating was spreading through my consciousness like lard, not the least because the nucleus of all this fiction, whether true or not, was verisimilitude and the distance it held to reality was constant. In other words, it saw the same. This sameness, which was our world, was being mass-produced . . . I couldn’t write like this, it wouldn’t work, every sentence was met with the thought: but you’re just making this up. It has no value.

Finally, after returning home from a visit to the region of southern Norway where he grew up, Knausgaard stumbles upon a new strategy: to alter the distance between the work and the world by getting “as close as possible to my life.” That evening, after his family has gone to bed, he sits down at his desk and describes what he sees in front of him:

In the window before me I can vaguely see the image of my face. Apart from the eyes, which are shining, and the part directly beneath, which dimly reflects light, the whole of the left side lies in shade. Two deep furrows run down the forehead, one deep furrow runs down each cheek, all filled as it were with darkness, and when the eyes are staring and serious, and the mouth turned down at the corners it is impossible not to think of this face as somber.

What is it that has etched itself into you?

This mini-scene repeats itself in My Struggle. Its first appearance is on page 28 of Book One. There, we read it as a description of the book’s brooding central character, an isolated, conflicted man. In Then, Again: The Art of Time in Memoir, Sven Birkerts writes that the genre “begins not with event but with the intuition of meaning—with the mysterious fact that life can sometimes step free from the chaos of contingency and become story.” 962 pages later, near the end of Book Two, Knausgaard’s mini-scene reappears verbatim. Only at this point do we learn the scene’s greater significance: that it is the turning point in Knausgaard’s attempt to write about his father’s impact on his life, the kernel that contains the six volume autobiographical saga to come.

While the above passage is a good example of how Knausgaard employs repetition across time to build meaning in his work, it also neatly enacts, in miniature, another type of movement the author utilizes in the My Struggle books to powerful effect: a quietly intense attendance to visual phenomenon, always linked to the act of perception/self-perception, with a particular emphasis on the perceiving apparatus (the eyes), will suddenly be followed by a shift to a larger, abstract question. (Indeed, Knausgaard’s epic, relentless attempt to answer the question that ends the passage – “What is it that has etched itself into you? – could rightfully be said to form the true subject of these remarkable books.)

But let’s go back to February, 2007: Knausgaard has just begun his new method. He seeks to “dramatize the inner self” by uncovering his past: first five pages a day, then ten, and near the end as many as twenty pages; he writes as quickly as possible in an attempt to escape his conscious notions of what the form should be, trying to move beyond the desire (amply exhibited in his previous novels) to produce aesthetically beautiful prose. By 2009, Knausgaard has accumulated 3600 pages. That same year, the first part of his novelistic “autobiography,” entitled Min Kamp (“My Struggle”), appears in Norway to equal amounts of praise and controversy. The controversy is not so much over the title, with its echoes of Hitler’s memoir (Mein Kampf in German, Min Kamp in Norwegian), but has rather to do with the people the author has “exposed.” In a northern European nation that prefers to keep family trauma private, Knausgaard has written directly about the most personal aspects of his family experiences without any attempt to disguise or change the names of his ex-wife, his father, his grandmother, and other friends and family. When the second volume of My Struggle appears, Knausgaard’s mother calls him and begs him to stop. An uncle threatens to sue. Ultimately, author and publisher agree to change a few of the names in subsequent editions, but the media storm grows, first spreading through Scandinavia, and then across Europe. Most agree about the power of the work, but at what cost has it been achieved? The books become a national obsession, selling 450,000 copies in a country of less than five million people. Norway’s culture minister declares the work the “the greatest account of our generation.” On a national radio program, Knausgaard will go on to say that he feels he has made a “pact with the devil.”

Last August, a few weeks before Archipelago Press released Don Bartlett’s excellent translation of My Struggle: Book One in North America, the book received the “James Wood treatment.” Writing in The New Yorker, Wood praised the work as “intense and vital,” stating that it contained “what Walter Benjamin called ‘the epic side of truth, wisdom.” The first volume of My Struggle is indeed a rarity in contemporary literature; part memoir, part unhinged bildungsroman, it ploughs through and ultimately transcends both genres with a driving seriousness of intent, delving more deeply into the human experience than anything I’ve read in a long time. Fixated on the shadow Knausgaard’s father cast over his childhood and teenage years, and ending with the thirty year-old Karl Ove confronting the horrible death of that father from alcoholism, the 430 page book alternates between extended, minutely detailed descriptive passages and essayistic meditations on death. The result is a kind of crackling slow-burn, a fearless examination of, as Carlos Fuentes once said of Frida Kahlo: “internal darkness under midday lights.”

This month, My Struggle: Book Two makes its North American debut. If Book One centered on death (in order to downplay potential controversy over Knausgaard’s Hitlerian title, the work was published as To Die in Germany and A Death in the Family in the U.K.) then Book Two is loosely organized around the concept of love (and has already been published across the pond under its subtitle A Man in Love). While it is possible to read Book Two on its own and still get something out of it, to do so would be like opening up Remembrance of Things Past for the first time at Within a Budding Grove. Much of the power of Proust and Knausgaard’s projects comes from their length and breadth, which allows for a gradual accumulation of patterned detail, as specific themes and moments repeat themselves in subtle and not-so-subtle variations. In both works, repetition is key.

My Struggle: Book Two primarily covers 2003-2008, years when Knausgaard left behind his old life and partner in Norway and moved to Stockholm. For readers of Book One, Knausgaard’s escape to Sweden possesses added significance: it was after Karl Ove’s own father moved away from his family that he began the drinking and isolation that fourteen years later would leave him dead. Knausgaard does plenty of drinking in Stockholm, but rather than fall apart, he falls in love – with the poet Linda Bostrom.

Knausgaard imbues these scenes with the nostalgic power of true love glimpsed in retrospect. He vividly captures the feel of early love, the uncertainty and vulnerability at the beginning, when things could still go either way, as well as the ecstatic heights:

The town sparkled around us as we walked home, Linda in the white jacket I had given her as a present that morning, and walking there, hand in hand with her, in the midst of this beautiful and, for me, still foreign town, sent wave after wave of pleasure through me. We were still full of ardor and desire, for our lives had turned, not just on the breath of a passing wind, but fundamentally. We planned to have children. We had no sense of anything awaiting us except happiness.

Over the course of My Struggle: Book Two, Karl Ove and Linda become parents to three children. One of the pleasures of the work is the associative, non-chronological way Knausgaard unfolds his story, shifting in and out of different periods according to the movement of thought and memory. Because of this, Book Two begins with all three children already born and the early stages of infatuation between Karl Ove and Linda a relic of the distant past.

The first thing one notices about My Struggle: Book Two (other than the fact that it is a hefty 146 pages longer than its predecessor) is a decrease in the level of intensity that filled Book One. With the father figure dead and buried, the sense of dread behind each sentence is palpably lessened. E.M. Forster once remarked that “mystery creates a pocket in time.” Book One utilizes the mystery of Knausgaard’s father (why is he such a cruel, tortured man? How exactly will he meet his end?) to mesmerizing effect. Throughout that first volume, wherever young Karl Ove goes, the father’s shadow follows; there is always the sense of movement towards further revelation. Many of the scenes in Book One possess an aura of somnambulant terror, as if anything could occur at any moment, which provides a momentum that propels the reader through some of the lengthier descriptive passages. A roughly 60-page description of young Karl Ove trying to secure alcohol for New Year’s Eve, for example, unfolds in painfully slow fashion beneath the constant apprehension over whether the father will find out what the son is up to. The tension builds until, at the end of Book One, Karl Ove pays a second visit to his father’s corpse (again, repetition). Here, something opens up in him, and he begins to see the intertwining elements of death, life, and time in a different way:

. . . there was no longer any difference between what once had been my father and the table he was lying on, or the floor on which the table stood, or the wall socket beneath the window, or the cable running to the lamp beside him. For humans are merely one form among many, which the world produces over and over again, not only in everything that lives but also in everything that does not live, drawn in sand, stone and water. And death, which I have always regarded as the greatest dimension of life, dark, compelling, was no more than a pipe that springs a leak, a branch that cracks in the wind, a jacket that slips off a clothes hanger and falls to the floor.

With this conclusion to My Struggle: Book One, the last two sentences of which rhythmically and thematically echo the final sentences of the first volume of Remembrance of Things Past,{{*}} the great tension is released. A new point of realization has been reached.

Initially then, Book Two lacks both the momentum and the mystery of Book One. Certainly love can be a mystery, but at the outset of Book Two it seems more like a daily slog, as we are confronted with scenes of Knausgaard’s new family life. Only in the light of what has come before do these scenes gradually accrue a resonant force. The still fearful, still internally isolated Underground Man persona that Knausgaard continues to develop here—picture a 21st century Raskolnikov schlepping a stroller, a diaper bag, and two toddlers up a hill while his wife stands at the top in a foul mood, a third wailing infant in her arms—is understandable precisely because we know what he has come out of. Although the hated father is dead and Karl Ove has escaped to a new country, Knausgaard still struggles to relate his internal and external worlds, and to be around others. Most moving, in these early scenes, is Knausgaard’s depiction of his own quest to be a decent father, as he attempts to raise his young children without duplicating the paternal coldness, cruelty and occasional rage he was treated to during his own upbringing. We come to see that for the adult Karl Ove Knausgaard, love means following through on one’s commitments, regardless of how fucked up one feels inside.

So it goes for 67 pages, with little of what contemporary publishing would call “narrative tension” or “drive.” As with certain sections of Book One, we begin to suspect that the day-in-day-out nature of these scenes, the very mundaneness of their details, is the point; these scenes need to be long for the same reason that the infamous sermon on hell in the third chapter of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man needs to be long: to enact, rather than simply describe the interminable, real-time duration of certain life moments. And yet, after a while, we begin to wonder if this is all Book Two has to offer.

Then, on page 68, Knausgaard returns home from the birthday party of one of his young daughter’s friends. He steps out alone onto the balcony, has a smoke, drinks some stale diet coke:

I returned the glass to the table and stubbed out my cigarette. There was nothing left of my feelings for those I had just spent several hours with. The whole crowd of them could have burned in hell for all I cared. This was a rule in my life. When I was with other people I was bound to them, the nearness I felt was immense, the empathy great. Indeed, so great that their well-being was always more important than my own. I subordinated myself, almost to the verge of self-effacement; some uncontrollable internal mechanism caused me to put their thoughts and opinions before mine. But the moment I was alone others meant nothing to me . . . Between these two perspectives there was no halfway point. There was just the small, self-effacing one and the large, distance-creating one. And in between them was where my daily life lay. Perhaps that was why I had such a hard time living it. Everyday life, with its duties and routines, was something I endured, not a thing I enjoyed, nor something that was meaningful or that made me happy. This had nothing to do with a lack of desire to wash floors or change diapers but rather with something more fundamental: the life around me was not meaningful. I always longed to be away from it. So the life I led was not my own. I tried to make it mine, this was my struggle, because of course I wanted it, but I failed, the longing for something else undermined all my efforts.

It is difficult to convey the full force of this passage without also including what preceded it: a forty-plus page description of a middle-class Swedish child’s birthday party, where a Norwegian father remains intensely within himself, unable to connect with the others, even those he likes. This struggle is made more poignant by the fact that we see how Knausgaard’s three-year old daughter Vanya already exhibits these same social tendencies, this same furious need to be accepted by others, coupled with the inability, on a bodily level, to figure out how to join in the other children at play. For Knausgaard and his daughter, a routine social occasion is a source of fear, shame, and longing.

A Few Words About Titles

Given that Hitler’s memoir is often published in North America, even in translation, under its original German title, for some the English “My Struggle” will not have the same resonance it does in Norwegian. The above passage from page 68 of Book Two is the first time we get a direct reference to, and partial explication of, the work’s title. Here, the emphasis is on the struggle to balance being in the world for others versus being in the world for oneself—the struggle to exist, on a moment-to-moment basis. In a recent interview, Knausgaard said that he chose the title Min Kamp on something of a lark. He liked the friction it carried between the daily, personal struggles of the individual and the larger structures of ideology and politics that function in opposition to private life. My Struggle: Book Six reportedly contains an essay that delves further into this issue, focusing on a comparison between Knausgaard and Hitler’s books, but English readers will have to wait a few more years for this.

If nothing else, Knausgaard’s series does foreground, in immense detail, the struggles of everyday life. By placing this struggle in the background, as the UK version does on its cover, the emphasis becomes reversed. Whether this retitling was done in order to avoid controversy or to more easily market the volume-by-volume content of Knausgaard’s work makes little difference; it interposes a too-large distinction between each book in the sextet, as if there were no significant overlap. The throughline of struggle is downplayed, the totality of the whole sacrificed for an emphasis on each volume as an individual marketable product.

For make no mistake, struggle, in conception and reality, runs through everything Karl Ove does, everything he thinks. Happy or sad, in joy or despair, he suffers apart from the rest, alone. In this, he is a true Underground Man.

Notes From Underground

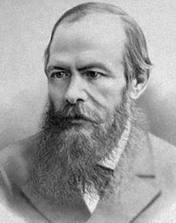

“All the same, if we take into consideration the conditions that have shaped our society, people like the writer not only may, but must, exist inthat society.”

—Fyodor Dostoyevsky

The above words (or rather, their Russian equivalent) were written in 1864 as a description the original Underground Man. Dostoevsky’s name appears 16 times in My Struggle: Book Two. Like Karl Ove in My Struggle, that main character of Notes From Underground is also a writer composing a sort of memoir: “I, however, am writing for myself alone, and let me declare once and for all that if I write as if I were addressing an audience, it is only for show and because it makes it easier for me to write. It is a form, nothing else; I shall never have any readers. I have already made that clear . . .” Interestingly, Knausgaard has said in interviews that he too “didn’t believe that anyone would be interested in this writing, because it’s so personal, so private.” This thought set him free at his desk, to write “for myself, by myself.”

As Dostoyevsky writes in a passage that applies equally to My Struggle’s central character, the Underground Man’s dilemma, “lies in his consciousness of his own deformity . . . the tragedy of the underground [is] made up of suffering, self-torture, the consciousness of what is best and the impossibility of attaining it, and above all else the firm belief of these unhappy creatures that everybody else is the same and that consequently it is not worth while trying to reform.”

While the Underground Man feels isolated from the rest of society, he is also a product of it, and perhaps, in the end, not quite so hideously unique as he imagines. Knausgaard realizes that his is as much a problem of perception as anything else, but does not know how to change:

Oh, fuck. Oh, fuck, fuck, fuck, how stupid I was. I couldn’t find any peace in a café; within a second I had taken in everyone there, and I continued to do so, and every glance that came my way penetrated into my innermost self, jangled about inside me, and every movement I made, even if only flicking through a book, was likewise transmitted outwards to them, as a sign of my stupidity, every movement I made said: “This is an idiot sitting here.” So it was better to walk, for then the looks disappeared one by one, admittedly they were replaced by others, but they never had time to establish themselves, they just glided past, there goes an idiot, there goes an idiot, there goes an idiot.

This paradox of the Underground Man, painfully separate from society, while at the same time yoked to and created by it, is presumably what allows Karl Ove to see himself as outside, different from the rest, and still write “the definitive portrait” of his generation, a work that has resonated so deeply for so many others.

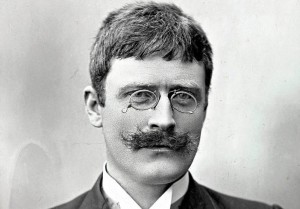

The other reference point for the Underground Man, particularly from a Norwegian perspective, is Knut Hamson’s Hunger. In the course of My Struggle: Book Two, Hamsun’s name is mentioned 11 times. In one scene, a Swedish filmmaker begins jokingly calling Knausgaard “Hamsun,” for his reactionary Norwegian views.

In Hunger, we are again presented with a writer struggling to maintain his dignity in an urban setting. Hamsun’s Underground Man is defined by his extreme refusal to partake in the pleasures of everyday life, to join the crowd by accepting help in the form of food or money. Knausgaard too is interested in refusal. Late in Book Two, Knausgaard’s friend Geir Gullickson informs him that: “Not to strive for a happy life is the provocative thing you can do.” A page or so later, Knausgaard responds: “All I know is that success is not to be trusted. I notice that I get angry just talking about it.”

Style

The prose of Book Two is similar to Book One: the long sentences and paragraphs do not induce anxiety in the way that Thomas Bernhard or László Krasznahorkai’s writing can, but rather project a certain detached calm. A typical Knausgaardian sentence piles independent clause upon independent clause, linking these with comma splices where grammatical convention would seem to call for a period, semicolon or coordinating conjunction. 800 pages into the My Struggle saga, these splices were still tripping me up. I began to wonder if it was a function of the translation; perhaps Norwegian possessed different conventions with regards to sentence structure?

A perusal of Knausgaard’s previous novel, “A Time for Everything,” revealed that the author does indeed know how to “properly” punctuate. A typical passage from that work reads: “Cain felt the gaze of the crowd at his back, but he didn’t turn; in a strange way their exit felt like a victory: it was just the two of them. In a few minutes the festivities would continue, and the wonder would dissipate itself in them.”

47 words in total. The varied punctuation helps to regulate the flow of the two sentences. We stop at the periods. And pause at the semi-colon and colon. Each of the two commas is followed by a coordinating conjunction (but, and). Now, compare this to the writing in My Struggle:

Later that autumn the temperature plummeted, all the water and the canals in Stockholm froze, we walked on the ice from Soder to Stockholm’s Old Town, I hobbled along like the hunchback of Notre Dame, she laughed and took photos of me, I took photos of her, everything was sharp and clear, including my feelings for her.”

One sentence, 57 words: one period, seven commas. My guess is that the run-ons in My Struggle are the result of Knausgaard’s compositional method, and that he decided to leave many of them untouched as a statement about the formal constraints of his project. As he recently told Eleanor Wachtel, length and speed were crucial: “It had to be long, and I had to write very quickly, so I could be ahead of my thoughts all the time.” By consistently eschewing the aesthetics of a properly punctuated sentence, Knausgaard allows data and detail to pile up without the emphasis that more varied punctuation would provide. At one level, the My Struggle books seem to be about getting as much of the world’s content as possible onto the page, rather than arranging this content for artful effect. Knausgaard will sometimes leave a sentence deliberately clunky to enhance this impression. Listen to the repetition of the word “mind” in the final clause here: “The boxer incident, when I hadn’t dared kick in the door, and the boat incident, when I hadn’t dared to ask Arvid to slow down, as well as Linda’s concern about my failure to act, had played on my mind so much that now there was no doubt in my mind.”

Eyes Within a Face

“What is a work of art if not the gaze of another person?”

—Karl Ove Knausgaard, My Struggle: Book Two

Which is not to say that there aren’t still beautiful passages and artful effects, but rather that these are not the point of the work. In particular, Knausgaard has a knack for describing eyes, getting at the essential individuality and emotion they convey. Knausgaard is obsessed, in a conflicting way, with how he sees the world and how others see him. It is little wonder, then, that painting is his favourite art (Book One contains a beautiful passage describing the eyes in a late Rembrandt self-portrait), or that the most frightening creature he can imagine, from a childhood dream, is a lizard-like figure without any eyes.

How Knausgaard perceives his own eyes often provides a clue to his relationship with the world. When he first arrives in Stockholm:

I studied myself in the mirror for a few seconds. My face was pale and slightly bloated, hair unkempt and eye . . . yes, my eyes . . . Staring but not in an active, outward-facing fashion, as though they were looking for something, more as if what they saw was drawn into them, as if they sucked everything in.

Since when had I had such eyes?

There is only one scene in Book Two where Knausgaard’s mother is remotely critical of him: after he moves to Stockholm, she lashes out at how he left his wife and then fell in love again so quickly: “I couldn’t see other people,” Knausgaard summarizes, “I was completely blind. I saw only myself everywhere. Your father, she said, he looked straight into people. He saw immediately who they were. You’ve never done that. No, I said. Maybe I haven’t.”

Later, his love for Linda changes the way he sees by bringing him into closer proximity to reality: “Before, I had always been deep inside myself, observing people from there, like from the back of a garden. Linda brought me out, right to the edge of myself, where everything was near and everything seemed stronger.”

Struggle with Form/Struggle as Form

“ . . . I could counter that Dante, for example, had written just fiction, that Cervantes had written just fiction, and that Melville had written just fiction. It was irrefutable that being human would not be the same if these three works had not existed, So why not just write fiction? . . . Good arguments, but that didn’t help, just the thought of fiction, just the thought of a fabricated character in a fabricated plot made me nauseous, I reacted in a physical way.”

—Karl Ove Knausgaard, My Struggle, Book Two

In Reality Hunger: A Manifesto, David Shields describes being overtaken by a similar feeling: “Every artistic movement from the beginning of time is an attempt to figure out a way to smuggle more of what the artist thinks is reality into the work of art.” It is worth noting that very few of the writers of recent works of reality-based fiction are as wholeheartedly against the traditional novel in the way that Shields can sometimes appear to be (e.g. Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be?, Francisco Goldman’s Say Her Name, Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station). It is tempting to add My Struggle to the list of contemporary fiction/nonfiction hybrids, the most epic version yet of the novel-from-life.

But somehow Knausgaard’s work displays a less playful attitude towards the division between fiction and reality, as if he is off working in his own mad dimension that paradoxically feels closer to the real. Though Knausgaard’s series was originally published in Norway and other European countries with the word roman on the cover, in Britain and North America it is more often referred to as an epic memoir. In many ways, My Struggle perfectly enact Birkerts’ definition of the genre. While “this really happened is the baseline contention of the memoir,” Birkerts writes, the true “fascination of the work . . . is in tracking the artistic transformation of the actual via the alchemy of psychological insight, pattern recognition, and lyrical evocation in a contained saga.”

Archipelago has wisely decided to publish My Struggle without a genre label. What ultimately matters is the magnitude of Knausgaard’s investment in his project, the sense that here is a man writing to save himself, writing to survive, writing because these things mean so much to him. Somehow, he is able to make them mean almost as much to us. Like all great art, whatever the genre, one leaves these books with a renewed feeling for what life and art can be.

Birkerts also stresses that it is the juxtaposition of multiple timelines, “the now and the then (the many thens) . . . that creates the quasi-spatial illusion most approximating the sensations of lived experience, of recollection merging into the ongoing business of living.” Knausgaard has taken this technique to new heights, returning again and again to his themes, with new insight:

Throughout our childhood and teenage years, we strive to attain the correct distance to objects and phenomena. We read, we learn, we experience, we make adjustments. Then one day we reach the point where all the necessary distances have been set, all the necessary systems have been put in place. That is when time begins to pick up speed. It no longer meets any obstacles, everything is set, time races through our lives, the days pass by in a flash and before we know what is happening we are forty, fifty, sixty . . . Meaning requires content, content requires time, time requires resistance. Knowledge is distance, knowledge is stasis and the enemy of meaning. My picture of my father on that evening in 1976 is, in other words, twofold: on the one hand I see him as I saw him at that time; on the other hand, I see him as a peer through whose life time is blowing and unremittingly sweeping large chunks of meaning along with it.

The overall effect of the first two My Struggle books, despite the seriousness of the subject matter, is both liberating and exhilarating. In any one book, so much has, of necessity, to be pared away. The magnitude of Knausgaard’s project allows him to shine a light on hitherto unknown aspects of being, indulging in immense, 234 page-long digressions into the past. But when we return to the present, it is with a renewed knowledge and understanding of the characters and their situations.

And yet, despite its allegiance to reality, Knausgaard’s art is still an art: it still employs form and illusion. For all its breadth, the writing still only seems to include everything. In reality, it casts its net only over what has come through the author’s mind in the process of writing. Gradually, as Book Two progresses, we move back round to the subjects and questions of Book One: alcoholism, death, paternity. We come to see that death and love are bound up together in myriad ways. But perhaps, with his particular brand of intuitive energy, Knausgaard was setting us up for this all along, right from the very first sentence of Book One:

“For the heart, life is simple: it beats for as long as it can.”

—Eric Foley

——————————————-

Eric Foley holds an Honours BA in English and Literary Studies from the University of Toronto and an MFA from Guelph University. He has been a finalist for the Random House Creative Writing Award, the Hart House Literary Contest, and the winner of Geist Magazine and the White Wall Review’s postcard story contests. His writing can be found online at Numéro Cinq and Influencysalon.ca. He lives in Toronto and divides his time between his writing and teaching at Humber College.

[[*]]In the Moncrieff/Kilmartin translation: “The places we have known do not belong only to the world of space on which we map them for our own convenience. None of them was ever more than a thin slice, held between the contiguous impressions that composed our life at that time; the memory of a particular image is but regret for a particular moment; and houses, roads, avenues are as fugitive, alas, as the years.”[[*]]

Karl Ove’s friend Geir in the book appears to be Geir Angell Øygarden, not his editor Geir Gulliksen.