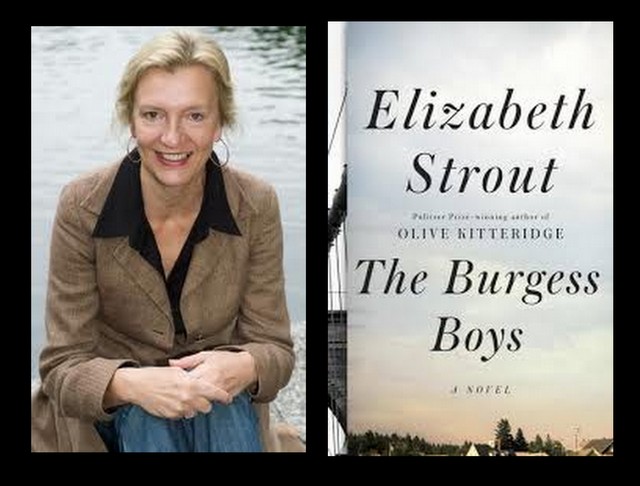

The Burgess Boys

Elizabeth Strout

Random House

320 pages, $26.00

Elizabeth Strout, who won the Pulitzer Prize in 2009 for her book of connected short stories Olive Kitteridge, has written an engrossing, strictly realistic, tightly plotted novel replete with family secrets, long-held grudges, and crises of faith and politics. Set in Olive Kitteridge’s home town of Shirley Falls, Maine, the new novel features a diverse cast of meticulously drawn characters who grow and change. The various braided stories in the book resolve with a sense of the past accepted and the future embraced.

In short, it’s everything a doctrinaire Modernist critic might be tempted to dismiss out of hand.

In his book What Ever Happened to Modernism?, Gabriel Josipovici asks the classic novelist,

What gives you the authority to decide that it will be this rather than that? No authority, the classic novelist will reply, but simply the requirements of realism, the requirements of my plot. But do these things have to do with anything other than ensuring your novel is saleable? That of course is a very reasonable requirement, but let us then simply relegate it to the world of consumerism, of fitted kitchens and package holidays.

His point is that the artificial tidiness and contrivance of conventional literary novels create an organized dream where “well-made” stories reach satisfactory conclusions and console us with a sense of ultimate meaning. But the universe is essentially meaningless, and any fiction which disguises this fact trivializes itself and accomplishes little beyond mere escapism. Life as people really live it moment by moment can only be described and honored by capturing the ongoing rush of consciousness. The attempt to grasp the unknowable, to sing aloud the intricate harmonies playing silently inside your head, is the true purpose of art.

So how does a writer working long after Virginia Woolf and Alain Robbe-Grillet, a writer of best-selling fiction in 2013, reconcile the demands of story-telling with this higher calling, this need to reveal that which stories, by their very nature, conceal? For Elizabeth Strout, it involves animating the machinery of her plot with moments of pure consciousness from the interior lives of her characters. It’s an uneasy compromise, and it certainly does not address the modernist need to “write against” and comment on the artificial constructions of the novel form. But it works. It lifts her book above the middle-brow pack, and lets the reader take away something surprising and ineffable, beyond the homely satisfactions of a tale well told.

The tale begins when Zachary, the 17-year-old son of Susan Burgess, shocks the town of Shirley Falls, Maine, by rolling a frozen (but thawing) pig’s head down the center aisle of the local mosque. The mosque is the central place of worship for the town’s Somali immigrants and Zachary’s bizarre hate crime casts an unflattering light, not unlike the harsh fluorescent lights in the local department store changing rooms, on the racism and xenophobia of this small northern village.

Both of Susan’s brothers, Bob and Jim, had fled the State of Maine years before to make their careers in New York City. They are both lawyers, Jim considerably more successful than Bob, but Zachary’s arrest brings them, however reluctantly, home.

The abiding narrative between the titular Burgess boys had begun decades before with a moment of horror that left the family splintered and scarred forever. All three children were left in a car by their father one evening and somehow Bob crawled into the front seat and released the emergency brake. The car rolled downhill, hit their father and killed him. Throughout his childhood Bob carried the guilt of that moment like a backpack bulging with textbooks, and the burden continues to deform him, well into middle age.

As for Jim, he was always the star of the family, football player, class president and eventually nationally prominent defense lawyer, most famous for getting beloved country music star Wall Packer acquitted in a notorious murder trial.

Jim is less successful in his attempts to intervene on Zachary’s behalf. He slights the governor after a rousing speech, and ineptly bullies the prosecutor. Similar errors of judgment contaminate both his personal life and his career. The two overlap disastrously when an affair with one of the paralegals in his office leads to a threatened sexual harassment law suit. Jim gets fired and divorced, humiliated in every way. He winds up using the last of his connections to secure a low-paying teaching job at an upstate college for rich slackers.

Lies have defined his life from the beginning. It turns out that it was in fact Jim who released the emergency brake and killed their father. Even at eight years old he was cunning enough to scramble into the back seat and position Bob up front, behind the wheel, so that his hapless baby brother would take the blame.

This revelation causes a tectonic shift in Bob Burgess’s life. The quake reduces all his assumptions to rubble. The hero and sovereign of his life becomes at a stroke nemesis and grifter, villain and fool, too awful to love, too sad and puny to hate. As for Bob himself, the curse he’s lived with all his life has lifted; he’s free. The liberation extends beyond his immediate family. His first wife Pam, who left him because they couldn’t have children, loses her hold over him as well: “Pam was gone for him. Gone with Jim somehow. The two of them seemed to have fallen into the pocket where the self knows to put dark unpleasant things …”

Pam is a complex interesting character and one of her private moments touches on the struggling modernism of this conventionally structured novel:

So she lay awake at night and at times there was a curious peacefulness to this, the darkness warm as though the deep violet duvet held its color unseen, wrapping around Pam some soothing aspect of her youth, as her mind wandered over a life that felt puzzlingly long; she experienced a quiet surprise that so many lifetimes could be fit into one. She couldn’t name them so much as feel them, the soccer field of her high school in autumn, her first boyfriend’s thin torso, the innocence unbelievable to her now, and the sexual innocence in some ways being the smallest part of innocence, there was no way to name the slender, true piercing hopes of a young girl in a rural Massachusetts town – then Orono, and the campus and Shirley Falls, and Bob, and Bob, the first infidelity … and then her new marriage and her boys. Her boys. Nothing is what you imagine. Her mind hovered above this simple and alarming thought. The variables were too great, the particularities too distinct, life a flood of translations from the shadow-edged yearnings of the heart to the immutable aspects of the physical world – this violet duvet and her lightly snoring husband.

Finally she arrives at the ultimate modernist conclusion: “Nothing could be told and be accurate.” Elizabeth Strout allows her character this thought, but the only way to ratify its fatalism would be to fall silent and this she refuses to do. She has a story to tell. The story of Bob’s liberation and his budding romance with the local Unitarian minister; the story of Susan Burgess’s struggles as a single mother, dealing with her son’s crime and his flight to Sweden to hide out with his expatriate father, his ultimate return home. And it’s the story of another expatriate, a Somali named Abdikarim Ahmed, separated from his own son, whose compassion for a troubled boy rescues Zachary both from the anger of the Somali community and the machinery of American justice.

Strout shows tremendous compassion for the Somali community and a sharp awareness of the discomfort of the locals as their community is knocked sideways from the comfort of its historically homogenous world into the era of diversity. Susan’s trip to New York City, which she finds almost as alienating as another country, gives her a faint sense of the overwhelming exile the Somali’s endure. But she can’t grasp, and probably wouldn’t want fully understand, the horror from which her new neighbors have fled. Strout allows us a glimpse of that nightmare, through the moments we spend with Abdikarim:

He should have left Mogadishu earlier. He should have put the two worlds of his mind into one. Siad Barre had fled the city and when the resistance group split in two, Abdikarim’s own mind seemed to split in two. When the mind occupies two worlds it cannot see. One world of his mind had said: Abdikarim, send your wife and young daughters away – and he had done that. The other world of his mind had said: I will stay and keep my shop open, with my son.

His son, dark-eyed, looking at his father, terrified and behind him in the street, and the walls becoming upside down, dust and smoke and the boy falling, as though his arms had been pulled one way, he legs another – To shoot was bad enough to last his lifetime and the next, but not bad enough for the depraved men-boys, who had burst through the door, the splintered shelves and tables, who swung their large, American-made guns. For some reason – no reason – one had stayed behind and smashed the end of his gun onto Baashi repeatedly, while Abdikarim crawled to him. In the dream he never reached him.

Ironically, it’s this loss, this raw view of authentic savagery that gives Abdikarim his compassion for Zachary and helps heal his adopted town.

As to Zachary, his motives are never really made clear. The central figure, the instigator of the story, remains a mystery. He mother is at a loss; so are his uncles. It’s doubtful whether even Zachary fully comprehends the impulse that drove him to bowl that pig’s head into a mosque during Ramadan. The feral distrust of the different had something to do with it. Susan expresses it this way: “They don’t want to be here. They’re waiting to go home. They don’t want to become part of our country. They’re just kind of sitting here, but meanwhile they think our way of life is trashy and glitzy and crummy. It hurts my feelings, honestly.”

So Zachary absorbs his mother’s baffled hostility, he feels separate and alienated, judged and invaded, angry and diminished. But at times he insists that it was just a prank, a random moment of perverse mischief, badly timed, horrifically inappropriate, drastically misinterpreted. None of the explanations add up to a coherent motivation, and that may be Strout’s point, the secret kernel of modernist non-meaning at the heart of the book that helps sustain all its tangled narratives.

As Josipovici remarks, discussing mainstream English novelists like Anthony Powell and Iris Murdoch,

They do what they set out to do perfectly and adequately: they help tell a story and create a world and characters to inhabit that world that do not flout the laws of probability. We never doubt what they are telling us … such narratives are easy to read. They are also illustrative in Bacon’s sense: they tell a story, they have no life of their own … the smooth chain of sentences gives us a sense of security, of comfort even, precisely because it denies the openness, the ‘trembling’ of life itself; the very confidence of the narrative gives the lie to our own sense of things being confused, dark, impossible to grasp fully.

And that, finally, is what Elizabeth Strout delivers in this fine novel: the openness, the trembling, of life itself. That she does this in a solid, deftly plotted piece of classical story-telling makes her accomplishment all the greater – and more mysterious.

—Steven Axelrod

—————————————–

Steven Axelrod holds an MFA in writing from Vermont College of the Fine Arts and remains a member of the WGA despite a long absence from Hollywood. In addition to Numéro Cinq, his work has appeared at Salon.com and various magazines with ‘pulp’ in the title, including PulpModern and BigPulp. A father of two, he lives on Nantucket Island, Massachusetts, where he paints houses and writes, often at the same time, much to the annoyance of his customers.