What is it like to be a brainy woman, lost in a world of books and ideas, pursuing the ineffable and the impossible under the gaze of great men? Herewith a scene from Unfolded, a new novel by my old friend Sheridan Hay, author of The Secret of Lost Things and the short story “Arise and Go Now” which appeared on these pages last year. In this scene we meet Delia Bacon, the gifted and scandalous 19th century American scholar/author who knew the greats of her era and went mad trying to prove that Shakespeare did not write his own plays. She published a 682-page book to explain her theory. Nathaniel Hawthorne, who appears in this scene with Delia, said of her: “no author ever hoped so confidently as she; none ever failed more utterly.”

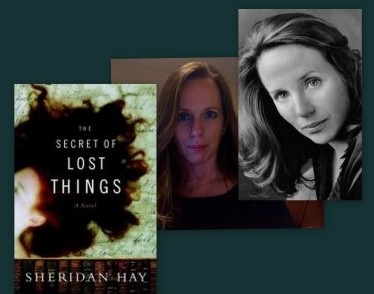

(The black and white photo above is by Marion Ettlinger.)

dg

§

As night faded from the front windows, a pallid dawn filled them. She prepared for his visit. Leaning over the porcelain bowl to wash her face, she read an indecipherable text in its cracks.

It would take hours to prepare because she must rest after each task. Moving in increments of will, stars burst beneath her eyelids if she went too quickly. Her hands seemed independent, taking up a hairbrush, a washcloth, the buttonhook. Every object in the room seemed far off and yet she saw with utter clarity, as if magnified.

Of her two good dresses, both now fell from her body. Needing no corset, she set it aside. Her bosom had flattened and a hollow marked the center of her chest. She chose the black silk. Its sheen was dull, like the coal she could not afford to burn, and whale stays gave it shape.

She took half an hour to arrange her hair, combing it through with water. Straightening her collar, she pinned a paste brooch at its center. She could not avoid the mirror: You go not, till I set you up a glass where you may see the inmost part of you. She was so altered as to be wholly unacquainted with who she had become.

Mr. Hawthorne would meet her revenant.

By afternoon she lay on the bed, hands trembling. She considered calling down to the Walker’s to refuse Mr. Hawthorne entry to the house. She has enough presence of mind to notice that anxiety makes one stupid. She would need calm in order to impress. Mr. Hawthorne had extended funds and Delia needed more than funds, she needed his good name.

His foot was on the stair. Mrs. Walker chattered away, breathless from the climb. He was ushered into the front room. She listened through the door.

“Mr. Hawthorne to see Miss Bacon,” Mrs. Walker called. A chair scraped the floor. Pages turned, he cleared his throat several times, but was otherwise silent. She felt the nervousness that used to precede her lectures in New York, when close to two hundred faces stared back from the long hall. Then, she had needed no notes; confidence had been a trick with her, and knowledge — the drumming into her brain of detail, of fact.

He stood as she entered, bowed. She had kept him waiting for longer than was polite, but no amount of time could have prepared her for his face.

Mr. Hawthorne was beautiful.

She stammered an apology, momentarily disarmed.

He did not speak at first, but motioned, pulling out the chair. Dark, thick hair was mixed with gray, and a brown moustache extended above a delicate mouth. He was tall, and wore a black frock coat; at his throat was a knotted scarf of white silk. She stared at his immaculate neckerchief as if she might disappear into its folds.

She thought it the prerogative of the recluse to be frank and it was with utter guilelessness that she gazed at him. But she felt that it was in fact mere loneliness that had robbed her of necessary pretense and Delia was suddenly ashamed – of her appearance, of her poor rooms, of what she needed from him.

“I have become picturesque!” She blurted, sitting down.

He smiled with great gentleness.

“Not at all, not at all. Thank you for seeing me, Miss Bacon.”

She took the hand extended. It was warm and soft and enveloped her own. He gave her back her courage with his touch.

“I have enjoyed our communications. Your enterprise interests me very much. But I am surprised. I had thought you older and not a young woman at all.”

Her eyes filled with tears for she saw he was sincere. He smiled again and she averted her gaze for fear of dissolving under his consideration. He drew up the only other chair in the room.

He’d had time to take in the piles of books on the study table – Raleigh’s History of the World, Montaigne’s Essays, Bacon’s Letters, Essays, and Meditations, a volume of the plays, a well used pocket Bible. More books were stacked on the floor. A large roll of manuscript lay partially unfurled. Lists neatly proclaimed their facts. A paper knife to cut pages lay across notes. She had the odd sensation of seeing these objects anew, and seeing too that their arrangement appeared theatrical — a stage with pen and ink-glass set aside, mid-composition.

In fact, here was the site of a great battle. She thought how strange it is when one’s intensions take on the appearance of staginess, as if one’s life is a fiction – oneself an actor. The scene, even to Delia, was suggestive of Mr. Hawthorne’s own Romances.

The vitality of his presence momentarily confused her and she sat in the chair as if she were the guest – a visitor to her own rooms.

She thanked him for coming and for his notes and told him he had sustained her at a time of great trial.

“I have been looking at your sources, and can only remark on your impressive scholarship,” he began, indicating the books. “Your reading of Montaigne is particularly fine.”

She nodded. This was of course the case.

“And the connections you draw between Plutarch and Shakespeare, between Bacon and classical literature are certainly provocative.”

“But you do not share my faith?” she asked, recovering herself.

“I do not,” he said. “I do not share your faith. But let me say that I think you nobly careless of authority, Miss Bacon.”

“And yet you offer help.” She felt encouraged by his interest if not his opinion.

“When I wrote to you, I expressed a fact which I firmly believe. Yours is an undertaking that must be valued. You are a gifted interpreter of Shakespeare’s plays, whoever wrote them.”

This would not do.

“Perhaps when you have read more of my philosophy you will feel that you know who did?”

“I am here at your service, Miss Bacon. My wife, Sophia, is already an ardent supporter, based upon the chapter you sent. And it is true that what sometimes seems most far from us is most our own to claim … but I am not of the converting kind.”

“It is not necessary that I should convey to others at once all the grounds of that absolute certainty on which my proceeding rests,” she told him, gripping the table’s edge. “It is enough for me to know, past all doubt, that it is as true as I am. I don’t expect you to follow, but I appreciate that Mrs. Hawthorne is a discerning woman.”

“That she is,” he said, smiling.

“Francis Bacon wrote that an immense ocean surrounds the island of Truth, Mr. Hawthorne,” Delia went on. “I cannot expect you to arrive on my island without an experience of the sea.”

He almost laughed.

“I would like to send you the chapter on Lear, after I make a fair copy, and after you’ve read that, the chapters on Julius Caesar and Coriolanus. You will see that my work is the discovery of Modern Science, the buried discovery which the necessities of this time have cried to heaven for, and not in vain.”

She brightened as she spoke, and gathered strength, but feared that he held little interest in the vagaries of her philosophy. Yet something in her manner compelled. What questions orthodoxy, she knew, was potent to him. She saw he felt her truth.

“Miss Bacon,” he said. “I feel that Shakespeare’s work presents so many phases of reality that his symbols admit an inexhaustible variety of interpretation… “

“You mistake the essence of my theory, Mr. Hawthorne.” She corrected him. “The history plays are a chronicle, a great whole. I am a teacher of history, you understand. It is because I have taught history that I was able to see the plays as a school, a school in which the common people would be taught visible history, with illustrations as large as life. All the world’s a stage was a cliché but not a metaphor. The plays are a magic lantern that depict and illuminate Bacon’s world.”

“But a magic lantern is called magic for a reason, Miss Bacon. It enlarges and also distorts; it makes a fairy world of shadows, and the truth is in the spell it casts not the reality it depicts.”

Viola slunk in, tilting her triangle head up at Mr. Hawthorne. She let out a cry.

“Ah, you disagree, Mr. Cat,” he said, addressing the animal at his feet. She wailed again and rubbed her face against the edge of his boot.

“That’s Madame Cat,” Delia corrected. “The mother of many tribes. I call her Viola, because I too thought her male at first. She was in disguise to win me. The landlord calls her something else, of course.”

“You make my point,” Hawthorne said quickly. “You might have called her Ganymede or Rosalind. The thing is itself with or without a proper name …”

“Not at all,” she shot back. “Shakespeare may well have been the name of a cat, but Bacon was the name of the author of these plays.”

For emphasis she placed her hand on the huge volume.

Words are spirit – her father’s admonition.

Mr. Hawthorne was not so ungentlemanly as to continue to correct her. There is no complacency in the plays, but Delia had found something like it in her certainty. If he thought her peculiar, he was a man for whom peculiarity was a rare value. He told her that his years in Liverpool had shown him all manner of strange things, but that he would try to be of assistance.

Delia told him that she needed to travel to Stratford-upon-Avon, that she would find evidence beneath the gravestone. She said she’d found clues in Bacon’s Letters and wanted to leave for Stratford as soon as she was well.

“Forgive me, my skepticism,” he apologized. “I mistrust all sudden enthusiasms.”

“There is nothing sudden in this,” Delia said. “It is the cumulative philosophy of years of study.”

“Sudden for me, I meant.” He smiled, determined and polite. “We find thoughts in all great writers, and even small ones, that strike their roots far beneath the surface, and twine themselves with the roots of other writers thoughts. When we pull up one, we stir the whole, and yet these writers had no conscious society with one another…”

“I know especially how the mind of an age speaks in many,” she told him. “And there is far more in this than merely that.”

She was becoming impatient, but Mr. Hawthorne’s mildness encouraged her further.

“You will read this manuscript with greater satisfaction and interest if you don’t bolster up your mind beforehand with any such false view as that. I mean with the idea that it is not true. It is true,” she said.

He adjusted his neckerchief, but said nothing.

“If the Inquisition were in session now on the question I could not give them a hair’s breadth of concession!”

“I hardly think …” he began, but she cut him off.

“Lord Bacon and these great men were a republic of wits,” she countered. “They knew and collaborated. Their goal was political. In that sense they are, to we Americans, our truest fathers. Lord Bacon hoped that all rulers would change places with those they governed, and thus become enlightened. He speaks to us in our freer age and we must follow his lesson. Even if it means welcoming the rude surgery of civil war … “

Silence fell between them. Delia suddenly spent, unable to sit up straight, unused to company and the effort required to convince. She had lost the habit of conversing with real people and insisted too much and without consideration for Mr. Hawthorne’s gentle courtesy.

He changed the subject. He spoke of Sophia’s illness, of his children, of the strains of working at his consulate tasks, which left him no time or energy for literature. People claiming to be citizens appeared daily to solicit funds either to return to America, or because they recognized in him a generous nature. He admitted to having been shrewdly cheated more than once.

“I see I tire you with these personal details.”

“No, no.”

“I came to assist you, and mean to.”

He gave her ten pounds. She took it with the unuttered acknowledgement that her earnestness had not produced in him even a temporary faith. He promised to work on her behalf to secure publication and knew English publishers likely to see of the merit of her philosophy. Perhaps, she thought, she had charmed him, when it was his faith she really wanted. He promised to consider writing the preface to her finished work, ensuring its serious consideration, and linking the name of Bacon with his own.

Perhaps Mr. Hawthorne saw her as a genuine scholar in a world of counterfeit. Had seclusion, single-mindedness and dedication, revealed to her something hidden from those who, like him, must serve the material purposes of the world? She could have told him that a prophetess must remove herself from ordinary life.

The effort to impress had left her hollow. She had played her part with enough conviction to leave her blank. The onset of a neuralgic attack loomed. Minutes after Mr. Hawthorne left, Delia fled to bed, still wearing her coal black dress, boots buttoned to the ankle.

— Sheridan Hay

———

Sheridan Hay holds an MFA from the Bennington Writing Seminars. Her first novel, The Secret of Lost Things (Doubleday/Anchor), was a Booksense Pick, A Barnes and Noble Discover selection, short listed for the Border’s Original Voices Fiction Prize, and nominated for the International Impac Award. A San Francisco Chronicle bestseller and a New York Times Editor’s Choice, foreign rights have been sold in fourteen countries.