“We wait for a thing, and when we come upon it, it is already in the process of turning.”

—Nathalie Stephens, At Alberta

Introduction

How to do justice to a text so rich that I could only do justice to it, as Charles Bernstein says, by repeating it exactly? The Obituary (2010/12) is the most challenging and enigmatic of Gail Scott’s works to date. It borrows a little something from each of her previous works, exhibiting an array of experimental techniques that are visible in her earlier work back to her first novel, Heroine:

The Obituary incorporates multiple perspectives, or multiple speakers which merge with one another (the protagonist and speaker R—or ‘I/R,’ or ‘Rosine,’ or ‘Rosie’—is both continuous and discontinuous, for example, with I/th’ fly, another speaker, and with ‘The Bottom Historian,’ yet another speaker). The subject, or self, The Obituary depicts is in this way porous; it is not unlike the protagonist of Scott’s Main Brides (1993), Lydia, who, as Jennifer Henderson points out in an insightful analysis, is never rendered in any depth, but is only accessible through the portraits she provides of the other women at whom she gazes, portraits ‘she,’ as a self presented, ultimately blends with (Moyes 72-99).

The self The Obituary depicts is also obviously fragmented (it splits off into multiple perspectives), a fact that is enhanced by Scott’s use, in the novel, of the sentence fragment as a main building unit. Scott’s use of the present participle—“Increasingly I am slipping. Yesterday, riding bicycle down sidewalk…sticking middle finger straight up…Trying by slightly bending th’ digital…Turning right + driving, still on sidewalk…” (7)—is intended to serve the same end: to allow the subject, literally absent from many of the fragments, to fritter away. These techniques become visible in Scott’s oeuvre with My Paris (1999).

The jarring syntax in both My Paris and The Obituary takes effort to acclimatize to; the language making up Scott’s prose in these two works actively draws attention to itself. Because it takes getting used to, it delays the reader’s—depending on the reader—absorption into narrative (though not forever).

Scott’s novels have all, in one way or another, attempted to reinvent narrative; they can be said to exist as part of the rich and motley tradition of so-called non-narrative.{{i}}[[i]]Scott’s writing grew out the experimental feminist writing scene localized in Montréal in the seventies and eighties; in Canada, around that time, bpNichol and Steve McCaffery were also toying with the idea of non-narrative narrative through their work on the book as a machine. This work emphasized the book’s materiality (some dimensions of which would be the look of words and letters used in a work and the use of white space on a page—the presence of suspect smirches on a particular copy’s page would count as well) and also attempted to dismantle the hierarchy between writer and reader, since the sort of texts they were theorizing were supposed to promote the reader’s participation in ordering the text—in choosing the sequence in which the text is read—among other things.[[i]] The Obituary, in particular, reimagines narrative structure as an improvised structure which exhibits recurring elements (in this case, tropes and specific questions) without seeming to head anywhere (while keeping a running commentary on the fact that it seems only to meander): Plot—at least understood in conventional ways: promise and the deferred fulfillment of promise; desire, thwarted, then navigated; conflict and the unfurling of its consequences—has a minimized place here and, as a result, the book does not lend itself to blow-by-blow summary.

‘What happens’ in the first section (“R, Negative”) continues to happen in each of the text’s remaining major sections (“The Triplex,” “Venetians That Even Private Eyes Have Trouble Sleuthing,” and “A Clue in R Case”), though of course not in the same way:

A face peers from the window in her Montréal, upper-floor apartment (her city is a fictional Montréal that, in many ways, has real-world resonance); the face is noted by different passersby, whom the narrative voice describes in excessive detail (conceptually-motivated excessive detail). Sections in which the face is present, gazing out, are intercut with sections in which R/protagonist, who is both continuous and discontinuous with the face, is moving through the city streets, either by bike or by bus, or is lying on her bed in the middle of her dark-centered apartment. In the sections in which she is described as lying on her bed, R might be dead, a corpse, or she might be masturbating, or she might be reflecting upon her family history (or on her lover, the absent addressee ‘X’): each of these possibilities is suggested. The Obituary refuses to decide between them.

The sections in which R is actively traversing the city occur in the fall, whereas those in which she is bed-bound tend to be set in the winter (there is ice on the sidewalks, for example). By the winter, specifically by November 2003, the face in the window, R, has been reported missing; two cops—a young, Québécois aspiring-actor who can’t seem to handle his food (he is highly flatulent) and an older Parisian virtuoso—have set up inside the stairwell outside her apartment. The Parisian peers in through her peephole and can perhaps see her there, on the bed; the younger gendarme sits a few steps down with a computer; at different moments he seems to succeed at hacking into her files. I/th’ fly is also in the stairwell, flitting about on the old cop’s shirt collar (“essayin’ little samba…I/th’ fly stickin’ backside out + swivellin’ to left, pirhouettin’ to right…” [76]). This fly/speaker is nearly omniscient: able to “see” into the apartment with the recumbent Rosie, or R, notwithstanding the apartment’s walls and closed door, and is also able to narrate the cops’ backstories.

The rest of the text in which the above ‘set-up’ is embedded, and repeated, reads like a collage of memory and history (the prose is densely reminiscent). As R rides about, either by bike or by bus, or simply reflects, the speaker, at times coincident with her, documents the city’s current process of transformation, the people in its buildings and streets, the hybrid languages and politics found there, as well as the play of events which helped shape the city into what it is (the labouring ‘Shale Pit Workers!,’ a smallpox epidemic, and the conflagration of the historical Crystal Palace building are recurring points of focus). As the narrative voice roves, it also documents the more encapsulating history of a country founded on genocide. Creative footnotes contribute to The Obituary’s historical enterprise, supplementing the main text with critical reflections, questions, and counter-memories (from “the margins of perception” [55]) which give the lie to dominant historical narratives. A footnote in the voice of The Bottom Historian reads, “What leads generation after generation of new arrivals in the Americas to endlessly iterate that everyone here an immigrant? From earliest fresh-faced settler boys enlisting, for economic reasons, soon leaning over pits + bayonetting every copper skin that moved…” (82).

R finds that the violent effacement of the Indigenous population is not even noted in the supposedly comprehensive Book of Genocides (on loan from her landlord), which she subsequently rips up, allowing the yellowing pages to scatter on the streets below her window (they become a recurring motif). Whether she is out and about or on her bed, R is haunted by this violence, particularly insofar as it permeates her personal and familial history: She herself is Indigenous, but her ancestry is spotty: it has been downplayed and, in some cases, actively concealed; she is unsure of the details. In the final section, “A Clue in R Case,” R addresses an absent grandfather with a few of the questions which agonize her:

Grandpa: on the subject of marrow. Was your paternal grandma Maria’s lack of family name meaning she Indigenous? Was the Canuck Maria marrying somewhere au nord du Québec mixed? Or pure laine? Was your father the Shale Pit Worker! fleeing smallpox epidemy, really marrying an Ojibwa somewhere in Ontario? Whose offspring [you, Grandpa] marrying [but why only saying after she dying?], the Métis, Pricilla Daoust… (158; brackets in the original)

These questions are not answered; they exist as instances or examples of hauntings and elaborate on the novel’s central preoccupation: R tells us early on that she is posturing as a woman of “inchoate origin” (we might read: an origin not formed, but forming and hence unknown) in order to “underscore how we are haunted by the secrets of others” (6). The text proceeds as a sort of sustained meditation on this subject: R, returning again and again, in different contexts, to the question of her origin, is not the only one haunted in the text: The passersby are haunted by R’s face in the window; the cop’s in the stairwell and her psychiatrist are haunted by the fact of her absence; those who have qualms with R, her neighbours, including her landlord—the latter because R set her sex toys out on the balcony one day, where they were plainly visible to children—“Dildo like a stallion’s!” (89)—are antagonized by the secret of what she gets up to in the privacy of her own home.

Scott has used the metaphor of ‘the spiral’ or of ‘roundness’ to describe the structure of her novel Heroine (1987), which proceeds in a similarly repetitious, meditative way (with the protagonist returning again and again to the question of whether her creative practice should be subordinated to political engagement, and to the somewhat masochistic ‘open’ relationship she is engaged in with a political leader, which is deteriorating). Heroine, as Scott discusses in her collection of essays, Spaces Like Stairs (1989), is supposed to enact a feminist politics of form while gesturing through its content and structure toward a conception of the self as, not only fragmented, but unfixed (the self could be or become anything). The Obituary enacts a similar politics and gestures toward a similar conception of the self, or subject. And yet it is also a text which actively resists reductive interpretations. It may seem impossible to have it both ways: to both inscribe the novel with a politics and to shun the idea of fixed meaning (this is one of the reasons postmodernism, a champion of unfixed meaning, has seemed so incompatible with, and has even seemed like such a threat to, feminism). In what follows, I examine the ways in which The Obituary, continuous, as a text, with other texts outside it, treads precisely this hard, paradoxical line. It is a feminist, postmodern novel if there ever was one.

/

A Politics of Form versus the Dead Author

It will be helpful to examine Scott’s poetic, as well as the feminist politics it implies, and the problem this politics might be said to pose for postmodernism, in greater depth before exploring the respects in which it plays out—in a way that is actually compatible with postmodernism—in The Obituary (at the level of the novel’sthemes, as well as at the level of its structure).

A poetic is typically understood as theoretical writing pertaining to an actual poetic practice, though poetry and poetics can intersect at times. Scott’s works have been marketed for the most part as fiction (novels, stories), though perhaps this term, in Scott’s case, is best reduced to a marketing label. Elsewhere she refers to her works as ‘prose experiments,’ and, in general, her writings refuse the sort of dichotomized mindset that would sever fiction from poetry. Why, Scott asks, quoting Ann Lauterbach, “should only poetry [be]…about the way language works (rhythms and sounds and syntax—musical rather than pictorial values) as much as it is about a given subject?” (The Virgin Denotes). In her collection of (at times also structurally and linguistically innovative) essays, Spaces Like Stairs, Scott expresses a desire for both poetry and the cultural legitimacy bestowed by ‘story’; at no point does she forsake fiction, though she does reconfigure it in order to better create, as she says, “stories ‘shaped’ like me” (67).

Her desire in this regard—to create stories “‘shaped’ like me”—is deeply indebted to the communal feminist/aesthetic practices that were specific to late twentieth-century Montréal. These practices, in which Scott herself participated, were informed by European French feminist philosophy and what we might call postmodern writings (writings by thinkers like Foucault and Barthes), which, given the absence of a language barrier, could find their way into that context independent of translation and mediation via academia. La Théorie, un dimanche (Theory, A Sunday) is a collection of essays by the writers working in that context and imbibing these European writings (Louky Bersianik, Nicole Brossard, France Théoret, Louise Cotnoir, Louise Dupré and Scott herself contribute essays). Its content reflects the conversations that transpired between these writers in a formal discussion group initiated by Nicole Brossard in 1983: meetings on different topics were held every two months, and the fruits of this sustained form of thinking were published in French in 1988. The English translation, Theory, a Sunday was only recently published—2013—by the American experimental press Belladonna.

There are several themes which recur in this text and which carry over into Scott’s Spaces Like Stairs, which was published a year later (in 1989). The possibility of a ‘feminine subject’ is a central concern. For these thinkers—though we can see the idea in the French feminist writings which were influencing them, particularly Hélène Cixous’ influential essay, “The Laugh of the Medusa”—“the feminine” expresses a gap, or black hole in patriarchal culture: it is something that has been misrepresented, distorted, and even actively occluded in a patriarchal setting, particularly by language as it is deployed according to the (patriarchal) norms and conventions (including literary norms and conventions) that govern this setting. The question for these writers is then how to score “the feminine” in culture through creative work that does not use the very language and literary forms that are deployed to obstruct it. This is a difficult task because, as they say, the patriarchal imagination not only governs the way in which women are represented (say, within works of fiction, or even within cultural narratives), but also preserves for itself the power to either validate or discredit works of literature—praising those which conform to its aesthetic and consigning those which do not to the proverbial gutters as either ‘green’ or ‘garbage,’ effectively exiling the author from prize culture and other avenues of legitimation.

The critique here is deep: It challenges the very criteria of literary valuation, which it recognizes is not neutral, demanding that its governing conception(s) of excellence be reassessed, and that we allow a descriptive rather than a prescriptive ethos to inform our engagement with new texts. As Louky Bersianik points out in her contribution to Theory, A Sunday, “a number of critics seem far too busy telling authors, especially female authors, what they should be doing instead of taking an interest in what they are actually doing” (64).

Scott’s Spaces casts light on the functional conception of the patriarchal aesthetic that serves as a backdrop for these writers’ thinking: In it, she suggests that linear narrative (with its linear time and cause-effect logic) and conventional sentences (which hammer subjects to verbs—in a later interview she also suggests that they “sentence” in a juridical sense, deciding things, definitively [Moyes 221-2]) may hinder the expression of “the feminine.” She also articulates a suspicion of the value of ‘action’ in narrative and conventional (possibly anti-intellectual) notions of accessibility, favouring writing which follows the ear, or lets language, lets poetry specifically, “take the lead in making ‘sense’ of the socially fragmented female ‘core’” (67). Those who care deeply about creating linguistically interesting sentences, or, even more generally, linguistically interesting text, may be more likely to appreciate the tension that exists between language that titillates the ears and is visually pleasing on a page and a focus on language as communication: It is hard to both control the direction of the prose and resist falling into ‘language as usual.’ As Nicole Markotic says, speaking as a writer of prose poetry, “[a]s soon as I take a step toward the horizon, the horizon reconfigures—itself and me” (“Narrotics” par. 5).

Consistent with this, some of Scott’s early critics claimed her prose consisted merely of “a whole lot of images going nowhere,” or, if they acknowledged a through-line in a given piece, claimed it was too distracted (Spaces 67). These qualities, of course, are not inherently negative (though the claim that Scott’s images go nowhere is overstated). Nothing in art is inherently negative, and these qualities in particular make sense within Scott’s theoretical framework, which suggests that “the feminine” might be best achieved in writing through the pursuit of poetry and the temporary suspension of plot, character, form, and “reasonable” writing more generally (reason has historically been associated with masculinity—femininity, conversely, has cultural associations with madness, chaos, emotion and puerility). “The more one transgresses,” Scott writes, “the more one distances from law and order” (73).

As I mentioned earlier, Scott has used both the metaphor of ‘the spiral’ and the metaphor of ‘the sphere,’ or ‘roundness,’ to speak of the structure of this alternative mode of writing she is engaged in, which, as she sees it, is conducive to creating stories ‘shaped like her.’ A story shaped like her, a particular female self who exists and writes from within a community of other critical female selves with whom she is not exactly uniform (since no self is), is, according to the theoretical framework she is working in, a story which bears the imprint of “the feminine” (“the feminine” therefore admits of no generic template). Scott’s politics of form—which is committed to bringing “the feminine” into view in a culture which has covered it over—insists that this imprint should be present: “the writing subject is not neutral, gender coding cannot be absent from the text” (Spaces 49).

This insistence on the trace of the author on the text at first seems to stand in opposition to a postmodern way of thinking—Barthes concluded his infamous essay “The Death of the Author” with the claim that the text (namely, the postmodern text) and the birth of the reader would have to come at the expense of the author: To attribute the text to an author in terms of whom the text could be read—the text could be read as a manifestation of the author’s psychology, or history, or could be read in the way the author ‘intended’ it to be read—was seen as a gesture which limited the number of ways it could be read: the meanings linked to an Author-God, rather than existing alongside other meanings, would eclipse all other possible meanings—they would, in other words, ‘close’ the writing. The postmodern mindset, reflected in pieces like Derrida’s “I have forgotten my umbrella,” is one, conversely, which values the proliferation of meaning, encouraging readers to promote this proliferation and to eschew reductive readings by relating to words, sentences and texts in a way which does justice to the nature of language—a system of signs whose meanings, according to this mindset, are always potentially infinite and have more to do with the way signs, or words, mingle with each other than they have to do with connections between words and the things in the world, to which they are usually said to refer.

This being said, the trace of “the feminine” can be thought in relation to the postmodern in a few ways: As the insisted-upon trace of the author (a gender coding which cannot be absent), it might be thought to threaten the text’s capacity to ‘mean’ in an unlimited number of ways (it might be thought to provide a lens for the text which, treated as the exclusive lens through which the text can be explored, will hinder a reader’s exploration of the work’s myriad other possible significations ). Alternatively, the trace of “the feminine” might be conceived as a harmless pseudo, or merely supposed, trace, since fixing “the feminine” as an imprint on the text would be, according to a certain postmodern way of thinking (there are, in fact, a few different postmodern ways of thinking), an impossible task to begin with:

This postmodern mindset insists on understanding the text as a network of words which not only do not gesture to a world beyond language, but also, in mingling with each other in an infinite number of ways, perpetually posit meaning, “but always in order to evaporate it” (Barthes, DA par. 6). The text, viewed from within this mindset, cannot actually possess an ultimate meaning, let alone an ultimate feminist meaning. Because the language that makes a text up is not supposed to refer to an outside world and the things within it (words merely refer to other words), it is supposed to be impossible to discover “society, or history, the psyche, or freedom” behind it (Barthes, DA par. 6). This particular postmodern mindset also makes the more extreme suggestion that there is in fact no society or psyche (let alone a feminist psyche) behind the text: All is text. Simply. As Christian Bök puts this in “Getting Ready to Have Been Postmodern,” “the play of the postmodern goes on to display a new atopia of humanist cancellation in a world without any certified existence” (89-90; in Stacey).

I would like to defer discussion of whether “the feminine” as a fact of existence “beyond” the text is actually incompatible with a postmodern perspective (a kind of postmodern perspective) until the final section in this essay. For now, I would simply like to examine the ways in which the thinkers of Theory, A Sunday are dwelling within and acknowledge the postmodern perspective as outlined above, while also exploring the respects in which “the feminine” as an imprint on a given work may actually be compatible with this perspective.

For one thing, the thinkers of Theory acknowledge that it is impossible to limit what a text can mean; they profess a desire to create works which refuse singular meanings, as well. Louise Dupré writes that “[t]exts written by women cannot be reduced to a feminist reading, even a well-intentioned one. They constantly resist such a process” (Theory 101). Even Scott is explicitly devoted to creating texts that remain ‘open.’ In Spaces Like Stairs, she insists that “[w]here there is closure (firm conclusions) in ‘straight writing’ there are spaces, questions in hers. Even her anecdotes point to other possible representations, leave themselves open for reader intervention” (102)—‘her’ in this instance refers to a writer of “the feminine.”

As far as “the feminine” goes, moreover, it is in many ways bereft of content. True, expressed as a gap in patriarchal culture, something covered up or distorted, the term seems to point toward something pre-existing, specific and perhaps ‘essential’ (an ‘essence’ usually implies content of some kind: it is the key trait or set of traits that makes something what it is). In Spaces, Scott recounts, for example, how at a colloquium a writer asked her what she meant in using the language of “listening to the animal inside her” (presumably while speaking about how “the feminine” might be accessed): “I had to admit I meant listening to something essentially ‘feminine’—perhaps to a part of ‘self’ (i.e., self-as-woman) not quite integrated into the law, closer to ‘nature.’ In [postmodernist] terms this was heresy” (52). Yet elsewhere in Spaces, she describes “the feminine” as having a changeable meaning: it could be or become anything (47). This shift in Scott’s vocabulary speaks to a kind of intellectual flexibility and provisionality on her part; it is also in keeping with the idea that the thinkers of Theory, A Sunday are consciously engaged, not in an act of making feminist ideology—they are not telling a story about an essential “feminine”—but in an ongoing, open-ended, critical process of thinking:

Taking risks. That’s what fiction does when in uncovers a woman-consciousness that goes beyond the feminist superego. In this moment when it seems that theory is spinning its wheels, when young girls see feminism as a form of ideology, a strict doctrine that accuses them for what is actually imposed upon them from the outside, writing allows for a conception of feminism that would be a space of discussion, questioning, change. In short, a conception of feminism as it actually is: a territory in motion, open, polymorphous. A movement. (Louise Dupré, Theory 101)

“The feminine,” like the feminine subject, or self, and like the thinking that takes her as a subject, or topic, and that articulates her in different ways, is difficult to pin down in terms of content precisely because it is always “in process.” It does not necessarily find expression in female characters as they are represented or in feminist themes, and, as a result, as Scott points out, writing which inscribes “the feminine” may not necessarily lend itself to “content-focused” feminist analysis: its feminism, in keeping with a literary tradition particular to Québec, instead plays out more as a “radical contestation of language and form” (Spaces 39). I would add that, if it is registered on a thematic level, it is registered more during those meta-moments when a given text (we will see that this is true of The Obituary) has the opportunity to explicitly reflect on what it is doing (compare Spaces 47).

What is “the feminine” then? If it is, in the ways I’ve been describing, content-less, it is not clear in what sense, inscribed in the text, it would limit, like the looming Author-God Barthes criticizes, the field of a given work’s possible meanings. We still might ask how “the feminine” might be understood. I stumbled upon a passage that is illuminating in this regard while reading Rob Halpern on the topic of New Narrative. ‘Community’ as Halpern discusses it—as a concept which denotes a content that is only ‘potential’—is in some ways analogous to “the feminine” in the sense that we’ve been discussing it:

[P]otentiality characterizes New Narrative’s approach to community not as something replete with self-present or transparent content, but as a set of lacunae, blanks, opacities that propose the collective as a question, a negative, a place-holder for something in excess of what it is given…This suggests the temporality of the future anterior…In other words, what will the present’s incoherence look like from the vantage point of the transformed future our story will have ushered into being…” (89)

Interestingly, the future anterior does crop up as a theme in The Obituary—perhaps it is the trace-mark of a larger conversation, since Scott does have ties to the New Narrative tradition in the States (they developed after she became established as a writer through her initial engagement with Québec’s writing scene in the seventies and eighties), or perhaps it is not. Regardless of whether it is or isn’t, the future anterior, as a tense that is a metaphor for a future vantage point, helps us make sense of “the feminine” as something which might be both politically effective (it may usher in a new way of thinking, a new world because, proposed as a ‘blank’ or ‘opacity,’ “the feminine” poses the gendered social world as a question, suspending its assumptions) and non-ideological and in this sense non-reductive: Hindsight may show it to have a discernible content, but until then, it is without one (unless its content is its dearth of content), and by then the world and “the feminine” within it will once again be transforming.

/

The Feminine Subject-in-Process in The Obituary’s Themes and Structure

“A sphere: a nice feminine shape to take off from, a shape that gives us the latitude to avoid linear time, that cause-and-effect time of partriarchal logic. Yes, the sphere is precisely the kind of shape, of movement, that permits us to leave reasonable prose behind. It’s a shape that abets (my) departure from a horizontal plane of writing, the better to decipher a memory blocked by silence, to leap from my discoveries towards a future not yet dreamed of. Twisting, altering in the process, the sphere itself…” — Gail Scott, Spaces 73

The prose making up The Obituary seems to meander. The text, which proposes a mystery and in many ways incorporates the tropes of film noir and the detective novel—we have R in the center of her dark apartment (though she may also be missing) and the two cops in her stairwell, who may see her or may not, and who are trying to solve the case of her disappearance, her possible murder—also gestures toward a direction the prose could take: It could move toward demystification, a denouement, toward the case resolved. And yet the novel only gestures toward this direction in a superficial way: it gestures toward the detective novel, toward crime fiction as a genre, only in order to subvert its conventions (particularly ‘the reveal,’ as well as the underlying assumption that there is a truth to be obtained); in doing so, the novel defines itself via a negative model (this is what I am not). Recurring themes and questions (which themselves are subject to variation as they are iterated) lend the text a degree of constancy without furthering the text along the path of knowledge. In this sense, the text’s structure is circular rather than linear (events do not unfurl and characters are not shunted along towards an endpoint, or the realization of a goal).

“The feminine,” I suggest, manifests in The Obituary, not only through the novel’s various repetitions, but also as a kind of digressiveness: as what seems at times to be the text’s improvised or haphazard, as opposed crafted, structure. ‘Digression’ takes the text afield of what is conventionally understood as good (reasonable) writing, in which all elements are supposed to serve some function (though it is never the case that every element in a text serves a function, and though it is always the case that every element, whatever it is, can be read back into a text so that it seems to). The Obituary’s seemingly improvised structure is also framed, in the text’s running commentary on itself, as an intentional and hence crafted structure, and the coexistence of these two possible meanings (such that the text can be read as both ‘improvised’ and ‘crafted’) functions to ‘open’ the text in a way that is consistent with a postmodern framework.

/

The Novel as Improv

The Obituary is typographically unconventional and a reading which focused on its visual presentation—a reading which paid attention, for example, to its plus signs and brackets, the line breaks which at times interrupt prose paragraphs, reconfiguring the space on the page, as well as the text’s playful lapsus linguae (its reference to Breton’s “great novel Najda” [100], among many, many others)—attempting to articulate its implications for the set of the novel’s possible readings would be valuable. Here, I will only point out that the inconsistency of its visual presentation—frequently varied spellings of “identical” words, the line-breaks I mentioned, the novel’s irregular abbreviations of ing- to in’-endings, and its irregular use of the hyphen along with the plus sign (as in “hurrying blue- + white-collar workers” [37] compared to “filth-+-vice-ridden city” [13] compared to more regular, unhyphenated combinations, as in “switching back + forth” [60])—seems to support the idea that there is no rule to this text, that it follows the idiosyncratic impulse of the moment (or that, more specifically, its “writer”—the writer the text implies, if not its actual author—was following the idiosyncratic impulse of the moment and for some reason chose to forgo editing).

Some of the text’s stricken words also belie the idea that there is any necessity behind its narrative direction: “Reeef, smiling rakishly, alongside Veeera his precocious little beauty Rosie. Already showing more leadership in her little finger than most” (121). ‘Veeera,’ the initially proposed focus, being Reeef’s wife. Rosie, swapped in, being his daughter. The text could have gone one way, but it went another. If we were to interpret the text’s omnipresent plus sign, which frequently takes the place of the conjunction ‘and,’ as a literal addition sign, then we could take its presence to suggest that the narrative progresses additively and is able to append whatever it happens to encounters to itself:

We are informed repeatedly, in different ways (which, taken together, make up the text’s meta-commentary) that the novel’s ambulation is and will continue to be that of the flâneur: random and indiscriminate, “subject to countless deviations” (25). In a footnote, the voice of The Bottom Historian tells us that, “Little by little revealing why we meandering in speaking. As disparate in associations as a voyageur on a train”; then, leaping off from her mention of the voyageur on a train, goes on in the same self-consciously meandering, free-associating way: “Hallucinating on various angles of the sunset, unless distracted by fussy table linen, or fancy brickwork or stations of the early era. When this still new, therefore allegorical, mode of transport advancing in winter night over ‘empty’ prairie…” (33).

Similarly, the “future novel space” is said to be opening “[w]ide as the legs of a porn queen” (24)—perhaps this can be taken to mean that it will admit much and admit anything.On page sixty, the novel absorbs and details a Cuban it confesses has “no future in R story.” Even one of the text’s major motifs, Hitchcock’s film Dial M for Murder, is introduced, or is presented as introduced, to the text in an aleatory manner:

A nobody in a bar R frequents notes that the washroom is “right out of Dial M for Murder” (24). The narrative voice goes on to describe his observation as “A serendipitous error. To use to our benefit,” then claims “Peter has served his purpose: / Dial M for Murder” (24). In other words, Peter, initially introduced, like the Cuban, haphazardly, and not because he had use-value, has come, it just so happens, to have use value: he has inadvertently provided The Obituary with a frame that it may now roll with; he has sparked an idea. It is illuminating, for example, to watch the film and to hear Mark Halliday, the crime-fiction writing character, explain to both Margot and her murderous husband why he believes in the perfect murder, but only on paper: “Well, because in stories things usually turn out the way the author wants them to and in real life they don’t—always.” And, in the film, of course, the husband’s plan goes wrong, and Margot destroys her would-be assassin with a pair of scissors. The Obituary chooses to shirk Halliday’s claim about stories and the relation authors bear to control and proceeds, conversely, as life in the film does.

/

The Novel as Crafted

If The Obituary does in some ways identify with Hitchcock’s film, however, it also collides with it, or contests it. The novel may suggest that it proceeds, not in the way of a novel, but as life does, and yet it also unsettles this idea: As much as the Dial M for Murder motif seems to be introduced haphazardly, it is also the case that it is presaged: it appears, dripping with intentionality, six pages before Peter in the bar, when R suggests that her apartment is “awkward as 3-D set of Dial M for Murder” (18).

The Obituary, moreover, despite its labyrinthine way of proceeding, despite its indiscriminate curations, its descriptive excesses and digressions, also remains puzzlingly on task. At least compared to a work like Vanessa Place’s Dies: A Sentence. Dies is anchored with a basic, recurring narrative frame—in this case, two people in different ways limbless, in a trench, awaiting onslaught, preparing soup—which, as Susan McCabe points out in her introduction to the work, freely recedes so that all manner of events and language can surge up, over and around it (xvii). The work lends itself to comparison with The Obituary because it, too, is a poetic experiment with narrative and is in similar ways friendly to digression and excess. However, whereas Dies tolerates sea-beasts bursting from ‘sea-sacks’ (see 43) and epic dungeon battles, The Obituary refrains from straying into the (overly) implausible or phantasmagoric. And yet The Obituary is, like Dies, intensely linguistic, sonic, odd: It is more than realistic (it is so linguistically specific it is less than realistic), only, unlike Dies, it is so without ever quitting a world whose historical and political valences resonate, uncannily, with our own. The following excerpt is in this way illustrative. ‘The face’—which is both continuous and discontinuous with R—has just streaked by the apartment’s peephole. It is

Ancilliarily coated in same dusky, near horizontal light penetrating inner stairway. Via Bottom oeil-de-boeuf door. Rendering our surveillants as splotches of miasma in corrupted stairwell air. Nitrogen. Methane. Ammonia from stagiaire J-F Jean’s [the young cop’s] steamy hotdog lunch. Dust mites. Scattered neurons. Dead ketones. Whorling swarms + electrons. Odour o’ p-p-p-patchouli from neighbouring sex trade worker. On whose scarlet salon wall hookers in blouses, long skirts, wooden trunks held over heads, themselves on way out West, ca. 1910. Crossing rocky steam in little boots. Walking walking toward red disc of a timepiece perched atop a craggy peak… (53)

The text suggests that this seemingly all-encompassing resonance, the way the novel, digressing, as towards the prostitutes above, remains so puzzlingly on-task, results from the fact that experience itself is over-connected (66). The novel, like the city in which its happenings are anchored, is saturated with history; any digression into history or memory, very capacious categories, moreover, is no digression at all, but aligns with the novel’s preoccupation with origins and genocide. In one possible reading, then, it is history, particularly but not exclusively the history of Indigenous erasure, which ‘over-connects’ experience, thereby giving rise to “th’ paranoia any citizen by definition trying to deflect” (ibid.). R/protagonist is, conversely, not a “citizen”; she is paranoid: She is trying to resist assimilation into a society of ‘better lawns’ and willed-ignorance, and, finding everywhere the traces of an undocumented genocide, goes missing herself. “Are not all paranoids,” her psychiatrist says, “self-fulfilling prophecies?” (ibid.).

/

A Gap in Lieu of Truth

R, as a character, is fractured; as a narrative voice, she blends with other narrative voices: those of I/th’ fly and The Bottom Historian, for example. She is also fractured in the sense that the novel refuses to make a decision about whether she is living and present, living and missing, or dead (murdered). She is also, like “the feminine,” or the feminine subject as we discussed her above, in her own way content-less. The mystery of her ancestry, of her origin, is at times presented as a major obstacle to identity (see 52). And yet ‘the truth’ regarding her ancestry, like ‘the truth’ regarding her disappearance, is tied, on a thematic level, to the novel’s (seemingly) improvised structure: the truth (whether regarding her ancestry or regarding her disappearance), the novel seems at times to suggest, is a mere improvisation as well.

I mentioned above that The Obituary subverts the conventions of the detective novel and the film noir, particularly by doing away with the requirement of a denouement; doing away with denouement is one way the novel subverts the premise that there is actually a fact about, for example, what happened, or about who murdered whom, or who attempted to murder whom (in Hitchcock’s film, the husband attempts to have his wife murdered), or even about R’s ancestry. The text is consistently ambiguous in this regard; different possibilities surface as R ruminates, but they are always framed in a way which calls their accuracy into question: “I/R [angry]: — I’m more Autochtone [exaggerating peut-être]. Than anything!” (59-60; brackets and italics in the original; “peut- être” meaning “a little”). Later, R states that, in school, “[n]o one teaching anything Algonquian.” (153).

The novel leads the reader on, perpetually making promises of a denouement (of answers) and gesturing toward a mode of arriving at it (them) which seems more suspect, more whimsical and jubilantly ineffective, every minute: “For a story, to be feasible, must be moving forward. Which is why I/R daily boarding avatar of public transport” (48). “Reader, in interest of dénouement, let us follow silhouette dégageant from wind-battered crowd” (125). Again and again, the text seems only to posit narrative direction as a pretext for its own persistence: “Is not our future narrative to keep us moving forward?” [9]—yetwhatever it decides to say or turn its eye on, no matter how tangential, will sustain the forward motion. Oh! it seems to say, in its various addresses to the reader, ‘Let’s do this because we can. I mean, trust us, we are heading somewhere.’ At various points in time, a voice surges up and claims to be setting the novel back ‘on track’ (“But let us stick to the path of our intrigue” [28]; “Here, it behooves I/Basement Bottom Historian, to surface. Encore. For purpose of resetting intrigue on path to dénouement” [115]); the novel’s meta-statements concerning its own self-reflexive aimlessness, however, work tirelessly to corrode a reader’s faith that this is actually what’s happening.

The recurring, repeatedly re-contextualized, somewhat enigmatic idea that “we are moulded by circumstantial evidence” also vexes the idea that, in the novel, there is a truth to be had, specifically a historical truth beyond history’s various tellings, which are themselves sculpted by the vagaries which weave the context from which they issue: “But we are moulded by circumstantial evidence, so for th’future…no visible dénouement [again, no interval during which truth will be ousted]” (55). “R little surrogate,” moreover, is at a loss to “secrete th’Méta Physique under th’ Topo Logic of reality [or, we might say, though there are multiple ways the phrase might be interpreted, the (non-extant) truth under a linguistic surface]” (144).

Even the young cop—a knowledge-constructor—sitting, once R has gone missing or has been murdered, or has simply barricaded herself in her apartment, a few steps down from her keyhole, working away on his computer, decides to assemble his final police report—the hard evidence, as it were—using a “hazardous selection method” inspired by Breton’s “Najda” (100). He collects: E-mails. Word Doc diary entries. “Chat logs. Police cams in trees. Phone tabs. Whatever. Gleanings he ideally formatting into little rotating loops, disappearing/appearing in no fixed order. Creating nifty multi-flash effect” (ibid.). Truth here is merely the clash of random documents, which, taken together, remain enigmatic and uninformative.

We could read the young cop’s random assemblage, which makes up a sizeable chunk of the novel’s penultimate section, as a mise en abyme, a small-scale version of what is going on in the novel on a larger scale: The Obituary in this way insinuates that its parts have likewise been haphazardly selected, while rendering the idea that we might glean from it, from them, through our readerly efforts, any kind of knowledge or clarification concerning R—that is, knowledge which exceeds the idea that she is a missing center—suspect.

The text’s final section (where its denouement would be placed, if there was one) takes a similar form: it is a motley gathering of flashbacks, epistle-form reminiscences, and sharp, sometimes sad images (I am thinking of an image of Veeera, R’s mother, who is dead; R remembers her “expiring on divan. Tummy swollen from sugar + wheat. Very pale from refusing in summer to let tanning sun fall, even on back of little finger” (162); she refuses to be dark, and there is a racial meaning here, since the text also suggests that she was raised unaware of the fact that she was iBndigenous.)

/

The Future Anterior in Poe’s “Ligeia” in The Obituary: Two Readings

To be sure, The Obituary is not a lighthearted novel. It depicts a self, a subject, with a gap at her core. It deftly confuses the truth of the subject with its own ludic way of unfolding, proposing, perhaps, that there is no truth below the surface of a narrative that just happens to happen as it happens. In a sense, it favours the reach toward knowledge (the act of questioning) over the possibility of attaining knowledge (the answer). The former, it sustains; the latter, it suspends indefinitely. At the same time, it showcases other ideas and features (like its meta-commentary) which trouble this reductive reading. Perhaps, it suggests, for example, the text’s structure is not improvised after all.

In a sense, the novel also suggests that R’s history, far from absent, is lodged in her in a way that is so concrete it could actually be related to her eventual murder. I would like to trace this tension in the text between the thought that R is, like “the feminine,” content-less and the thought that she is overdetermined by her history (the thought that her ancestry determines her destiny). The Obituary refers to many outside texts—among these: Breton’s Nadja, Hitchcock’s film, which we discussed, Shakespeare’s Macbeth as well as Romeo and Juliet, and Edgar Allan Poe’s “Ligeia.” It uses these texts to frame its own preoccupations. It is “Ligeia,” in particular, that can be read alongside Scott’s novel in a way which brings out the idea of an oppressively present past, or origin.

/

First, A Note on the Ghost of the Author

So far, I’ve been reading The Obituary largely in terms of the framework provided in Scott’s Spaces Like Stairs and in the collaborative work Theory, A Sunday, so I provide this new reading (making use of Poe’s “Ligeia”) partly as a way to deviate from that framework. Contra Barthes when he claims that “[t]o give an Author to a text is to impose upon that text a stop clause, to furnish it with a final signification, to close the writing” (DA par. 6), I want to examine the way in which the thought of a feminine-subject-in-process, possessing a content which might only come into sight retrospectively, exists as only one lens among others through which the work might come into focus. Yet, I want to insist that, in this case, a reading that hews (in a way certain postmodernists would find dubious) to what Scott, or The Author, has said about her own work is a necessary supplement to the alternative reading I outline below: it keeps this alternative reading from having what postmodernists should find even more dubious: a monopoly on meaning (the text’s possible meanings are supposed to be infinite).

As far as the question of whether “the feminine,” which I have suggested is inscribed in various ways in The Obituary,{{ii}}[[ii]]Through its structure, when that structure seems improvised, through the running commentary it keeps on that structure, which gives the lie to the idea that it is fully improvised, and through the novel’s repetitious concern with what it means to be haunted, as R is, by the secrets of others, which I mention in the introduction.[[ii]] refers to something “beyond” the text goes…The extreme version of postmodernism suggests that everything is text, that there is no world and no self “outside” of the text, never mind a feminine subject which might be inscribed in the text for political purposes, namely, in order to bring that subject into view in a culture which has ignored it. And yet postmodernism is also a perspective that refuses hard and fast distinctions between opposites; it is in this sense a way of thinking which in theory should actually resist the idea that texts and selves, or even texts and the world, could be thought in any way other than in relation to each other: The thought that ‘all is text’ is too one-sided for this way of thinking.

In writings like Of Hospitality and “Violence and Metaphysics,” for example, Derrida collapses ‘self’ into ‘other’ and ‘inside’ into ‘outside’—he writes these concepts out in a way which allows us to see that these so-called opposites actually participate in each other, and that they wouldn’t be what they are if they didn’t. The subject, or self, that Foucault theorizes (from different angles in his early and late works) is likewise saturated with what is sometimes conceived as its “outside”: cultural norms as well as the writings and categories which make up the available means of self-interpretation. Foucault’s subject is, in many ways, just this “outside” in the sense that such texts make up what Foucault wouldn’t but what we might call its psychology.

This idea does not have to be taken to imply that the self is “only” text. The philosopher Seyla Benhabib goes this route when she argues that the self cannot be understood as both language, or text—as part of “the chain of significations of which it was supposed to be the initiator”—and as a political agent: If the self is only a “position in language,” then, she supposes, it cannot reflect on and alter language, let alone the world through language (a situation which leaves postmodernism and feminism looking pretty irreconcilable). Judith Butler’s works Giving an Account of Oneself and The Psychic Life of Power, conversely, encourage us to rethink the self, and its ability to act, as a paradox: as consistent with the idea that the social world’s normalizing categories and practices make up the self’s proverbial tissue, while at the same time making agency (mainly in the form of self-change) possible.

Postmodernism’s “dead” author can be thought of, then, in a way that is perfectly consistent with postmodernism, not as an instance in which the writer, or self, and world are abolished, but as just another instance in which self and other, and inside and outside, blend. When Barthes claims, for example, in “The Death of the Author,” that if the writer “wants to express [read: insists, naively, on expressing] himself [sic], at least he should know that the internal ‘thing’ he claims to ‘translate’ is itself only a readymade dictionary whose words can be explained (defined) only by other words, and so on ad infinitum” (par. 5), this claim in itself does little to discredit the idea of a feminine subject (rethought), in the world (rethought) beyond (even the idea of ‘being beyond’ must be rethought) the work. It also does little to discredit the idea of a feminine subject, leaving a trace on the text, or participating in the work as a frame which sits alongside and only sometimes inflects its many other meanings: Writing, as Barthes says, “ceaselessly posits meaning but always in order to evaporate it” (Barthes, DA par. 6)—why couldn’t a novel, then, posit “the feminine” in the way it posits any other kind of meaning: ephemerally?

All this being said, I should acknowledge that “the feminine” I’ve read into The Obituary has been relayed through another text (a book of Gail Scott’s theory): All I’ve truly done is read one book in terms of another by the same author. The above discussion has not been fruitless though, because, having read the “novel” in terms of the “theory,” we would still have to wonder whether a form of culturally-downplayed feminine experience could be said to exist “outside” of these paired works,and we would still have to wonder if articulating the feminine, whether in theory-form or fiction-form or via some inter-genre, such as Scott tends to work in, is both, even from within a postmodern way of thinking (since I am attempting to read The Obituary as a specifically feminist postmodern novel), possible and meaningfully political. If all is text, brute text (as opposed to text as the nuancing folds of Judith Butler’s mind make it out to be: text can take the form of a living self), then it is hard to see how anything other than the “new atopia of humanist cancellation” Christian Bök associates with postmodernism could be possible.

Reading The Obituary alongside Scott’s Spaces is a (postmodern) fair move. Any piece of writing is an entity with questionable boundaries, after all (remember that strict distinctions like ‘inside’ and ‘outside’ lapse from within a postmodern perspective). To speak metaphorically, a book extends into, or takes in, the other works to which it refers. It can also be joined, through a reading, with any number of other texts. (And the author is perhaps just a text of a different sort.)

/

“Ligeia” (R/protagonist as Rowena)

Edgar Allan Poe’s “Ligeia” is a more conventional sort of text embedded in The Obituary. The young Québécois cop siting in R’s stairwell is also a drama enthusiast and is planning to audition for a night-school performance of a play based on Poe’s story. Other details strewn about The Obituary also serve to connect it to “Ligeia.” A brief summary here, so that I can draw these connections out:

In the tale named for her, Ligeia is a woman of angelic beauty and unsurpassed intelligence; her dark eyes, “orbs [of] the most brilliant black” (570) (which pop up at various places in Scott’s novel), according to her husband, the narrator, are her defining features. She falls ill, then passes. After losing her, the narrator purchases a gloomy abbey in England, where, in one of its decadently ornamented, though strangely moribund, chambers—perhaps it is the presence of vertical sarcophagi that does it—he takes another wife: Lady Rowena Trevanion, of Tremaine, though he continues to suffer his memories of Ligeia, mourning what, to his mind, had been an ideal marriage.

After their second month together, Lady Rowena takes ill. She summons her husband to her bedside on the night she is sure to die; she appears to be fainting, and so the narrator leaves her side to procure, from elsewhere in the chamber, the same chamber in which he had married her, “a decanter of light wine which had been ordered by her physicians” (576). But as he goes to fetch the wine, he feels “some palpable although invisible object” pass lightly beside him and notices “upon the golden carpet, in the very middle of the rich lustre thrown from the censer, a shadow—a faint, indefinite shadow of angelic aspect—such as might be fancied for the shadow of a shade” (ibid.). He also becomes aware of “a gentle footfall upon the carpet” (ibid.). He returns to Rowena and gives her the wine, but as she drinks, he notices a few drops of ruby fluid spring, “as if from an invisible spring in the atmosphere of the room” (ibid.) into the goblet. Rowena’s condition immediately worsens.

Soon afterwards, she dies. Around midnight, the narrator, who has stayed with the body, hears a sob. In fact, Rowena is not dead, he determines: there is colour in her cheeks; he hastens to resuscitate her. But all is in vain, for the colour drains off and a “repulsive clamminess and coldness” (577) colonizes the body. The narrator returns to his wake, sitting in the ambient dreariness, eyeing the corps. The clock rolls on and once more he hears something: a sigh, this time. The corps nearly grins: the lips disclose “a bright line of pearly teeth” (ibid.). There is “a slight pulsation of the heart” (578). The narrator responds again with all of his impotent urgency, but the corpse, once more, becomes corpse-like. Until the grey dawn, we are told, the narrator navigates, again and again, this “hideous drama of revivification” (ibid.)—until, finally, the corpse is committal: Its stirrings become more vigorous than previous stirrings; it stands and advances “boldly and palpably into the middle of the apartment” (ibid.). The shrouds loose off, and the narrator knows, by its indisputable eyes, that it is Ligeia.

In The Obituary, mention of ghosts is frequent. Early on, R, during one of her excursions into history, speaking of British officers, tells us that “They were rumoured not to like girls like me very much. / They also hated Indians. / This is better documented. / By the end of our tale, we may likewise be dead” (7). The stricken word ‘dead’ is, of course, because stricken, ambiguous, but the novel also suggests, at various points, that R might return as a ghost (47 and 115) (at any point in time, it is unclear, of course, whether she is dead or alive). At one point, as the young cop hunches in the stairwell, working on his computer, a “[w]hite light spot bob[s] back out 4999 Settler-Nun casement” (150)—4999 is R’s apartment number. Ligeia’s disembodied shadow on the carpet in Poe’s tale, as well as the narrator’s ghostly rubbing and the soft patter of footsteps he mentions, resonate with The Obituary at this moment in particular.

A few of The Obituary’s subtitles as well as the title given to the novel’s last section also link Poe’s dreary bridal chamber, which is also a death chamber, to R’s shadowy bedroom (the center, we are repeatedly reminded, is dark, and that is where she, or possibly her corpse, lies). These are “The Crypt’s Tale,” “Her Little Shelf a Cemetery,” and “A Clou in R Case,” respectively (“a clou in R case” sounds like “a clue in our case,” and can take on that meaning, but once the French word “clou” is translated, it literally becomes “a nail in R case,” which might be taken to mean something like “a nail in R’s coffin”). The “hideous drama of revivification” Poe’s narrator witnesses, moreover, finds an echo in The Obituary’s back-and-forth between autumn scenes in which R is out, roaming about the city, and winter scenes in which she is (possibly) dead in her apartment.

The most striking connection between Scott’s novel and “Ligeia,” however, is the absence of R’s shadow in a vision her fortune-reading grandfather somehow conjures in a teacup: “Black eyes [remember Ligeia’s], blonde curls, skating on future ice of big dark city. Something happening but winter keeps her warm. Entirely my sentiments, old man thinking. When beholding, in bottom of cup, time going on back. Out Room door. Stairs. Yellow leaves, also exiting court. What alarming Grandpa most: his little Rosie casting no shadow” (119-20). R’s absent shadow is, of course, the inverted figure of the shadow Poe’s narrator observes on the carpet, which is not attached to a body (but which may be attached to a ghost), yet both details stand out because they are curious. R’s absent shadow is suggestive of Ligeia’s unaccountably-present shadow because it is equally curious.

In all of the ways just outlined, The Obituary self-consciously aligns itself with “Ligeia”; because it does so, it becomes possible to read “Ligeia” in terms of The Obituary’s themes; it also becomes possible to read The Obituary in terms of the “Ligeia” which emerges when Poe’s text is read in terms of The Obituary’s themes: The Obituary, relayed through “Ligeia,” embellished there, returns to The Obituary. The character Ligeia can be read figuratively, specifically as a representation of R’s history, ancestry, or what she terms her origin, and this reading has consequences for the way we might read The Obituary.

Ligeia, the narrator’s former wife—her life has, quite literally, passed, such that she, and the narrator’s former life with her, are things of the past—readily lends herself as a figure for the past, or history. In Poe’s tale, however, she is fully restored, if the narrator is to be believed, to the present through the body of the hapless Rowena. It is possible that she even destroys Rowena or abets her illness so that she can take her place (red drops spurt, as if from an invisible spring, into Rowena’s cup, and we might associate this event with Ligeia, whose presence as a ghost has just been implied, and conclude from the fact that Rowena’s condition, once she has had her drink, immediately worsens, that the drops were a poison of some kind.)

Linking this reading back to The Obituary, we can note, once more, that R, noticing everywhere the traces of an undocumented genocide, herself goes missing. “Did not Auntie Dill,” R ruminates, “sitting on her scooter outside Starby’s in Kelowna…reply when asked what colour Grandma’s hair was, hint of panic beneath her perfect curled lashes:/ —N-O-T N-O-I-R [not black, or not dark]” (16). The fact that R’s is Indigenous, though she does not know the particularities of her ancestry, is significant. When speaking of the British officers mentioned above, she says, “They were rumoured not to like girls like me very much. / They also hated Indians.” Of course, ‘girls like me’ could, given what we know about R, also mean girls who happen to be Indigenous. This interpretation makes sense in light of the way R finishes her thought/verse: “They were rumoured not to like girls like me very much. / They also hated Indians. This is better documented. / By the end of our tale, we may likewise be dead” (7). The pronoun ‘we’ in this last sentence is ambiguous, however it does include R: if R is Indigenous, then the British (a figurative stand in for a more general cultural force perhaps) will kill her like they killed the other “Indians” they hated.

The origin which obsesses R, in a sense, and on a figurative level, in the way Ligeia overtakes Rowena, does her in. She cannot escape it: “Do not skyscrapers bear, deep within, straw huts? The person, her ancestors?” (115). She perhaps, the novel insinuates, in the past, even attempted to escape her origins (she has a dream about her mother, who is accusing her of lying about her origins [ibid.]; in the text’s final section, in an address to her grandfather, she also explains a move across the country as a way of attempting to become authentic, a state of being she associates, with having origins, with being either able, or willing, to remember them, all of which implies that at some previous point in time she was ‘inauthentic,’ either unable or unwilling to affirm them [see 152]). In the end, however, R does not escape her ancestry: she still goes missing, as if her Indigenous blood has marked her, such that she cannot be an exception to the genocide she has trained her eye on. “It is so easy to be murdered” (157), she tells us.

Read against the backdrop of Poe’s story, R’s ‘origin’ comes into sight, not as a gap, but as a concrete, future-determining presence. As such, it gives us an alternative way to understand ‘the future anterior’ at those moments it surfaces in the novel (we already encountered Rob Halpern’s version). ‘The future anterior,’ as a grammatical tense, signals the idea of a past which is not yet a past, but will be a past at a future point in time (‘she will have returned by tomorrow’). In other words, it is a future past, or, stretching things (figuratively again), it is a past lodged in the future (like Ligeia is lodged in Rowena’s body). (In the novel, the future anterior is presented as the figurative location at which “all stories are told” [46], a domain which is, according to R, “the realm of the ancestors” [152].) But this past lodged in the future is also described as a monstrous one: R refers to “th’ future [+ th’ anterior within it]” as a “monstrosity” towards which she is “obliged to keep movin’” (145; brackets in the original). The fact that it is described as monstrous is consistent with and supports a reading in which “th’ anterior” within “th’ future” is understood as one representation of R’s origin, or ancestry, which, pitted against an enduring cultural hatred, ensures her annihilation. Again, it is no coincidence that she goes missing: she is Indigenous, and her ancestry haunts, and governs, her future, which it expunges, much like Ligeia blots out Rowena. Her ancestry, on this reading, both provides and exhausts her ‘content.’

This take on the future anterior is, of course, markedly different from the one Halpern provided us with in suggesting that the ‘community’ New Narrative writing sometimes takes as its focus is always only a potential community: it is posed as “a set of lacunae, blanks, opacities that propose the collective as a question, a negative, a place-holder for something in excess of what is given,” rather than inscribed with a specific content. Above, following Halpern, I took the future anterior to imply that retrospection from a not-yet-existing (future) vantage point alone can make sense of what, at present, may seem to be a given novel’s chaos or nebulous ambiguity. “The feminine,” in Scott’s work, like New Narrative’s community, might come into sight as having a specific content from this vantage point, but, until then, remains a gap. Of course, ‘the future anterior’ might be interpreted in a more extreme way as well: It can be taken to mean that what a given novel—and whatever it preoccupies itself with, whether a community, as in Halpern’s case, or “the feminine,” in Scott’s—never means anything (any one thing) in particular and always only will have taken on a particular meaning, since a future tense remains a future tense (it does not, like the non-grammatical future, become the present, and then the past), and since this implies that the future vantage point the tense implies, not to mention the ‘content’ visible from that vantage point, is one which never arrives.

The future anterior, a theme in Scott’s novel, taken in this last way, dovetails with the idea of a (content-less) feminine-subject-in-process expressed in the work, where it is manifest partly as a structure that seems to wander, repeat itself and, ultimately, head “nowhere”—a structure which is the possible effect of an unconventional and, perhaps in many contexts, culturally disavowed approach to writing—a “feminine” approach, to use Scott’s terminology—which eschews logic linearity, knowledge and fixed endpoints, and instead pursues poetry in a way which allows the writer “to leap from [her] discoveries toward a future not yet dreamed of” (Spaces 71). It also resonates with the postmodern attitude which understands a given work’s meanings as open-ended and infinite (meaning only congeals at a never-arriving vantage point). It is in this strange way fully compatible with the alternative interpretation of ‘the future anterior’ which emerges when we read The Obituary alongside “Ligeia,” though the reverse is not true, since the version that emerges through this joint reading points towards the thought of an origin as the self’s—as R’s—fixed content, and also as a guarantor of death (her fixed end), which itself would depend on a fixed interpretation of the work.

Yet both meanings (and many more) emerge in the work, where they trouble each other. In fact, many of Scott’s sentences and sentence fragments have been crafted in such a way that they maximize possible interpretations and minimize situations in which one interpretation could become dominant: “By the end of our tale,” R tells us, “we may likewise be dead” (7). The word ‘dead,’ stricken, I mentioned above, is ambiguous. Because “dead,” in this sentence, is stricken (not absent, but still implied under the strike mark), the sentence might be read conventionally: “we may likewise [like the “Indians” the previous sentence refers to, and whom the British officers despised] be dead” (my emphasis; “may,” here, introduces another element of ambiguity, since it indicates a possibility, not a necessity). Or it might be understood in an opposite way (since ‘dead’ is, for all that, crossed out): “we may not be dead” or, more specifically, we may not, like the “Indians” the British officers despised, be dead: in one sense, they are not dead because they continue to haunt R. And a ghost—which R may or may not be—is itself an ambiguous figure: it is both dead and present, both dead and, in a sense, living.

/

The Obituary posits meanings constantly, but only to evaporate them. Interpreting the novel is part of the pleasure of engaging with it, and because of the way the novel is written, it will remain perennially interesting. The first time I read this book, about two years ago by now, I read it quickly, and not for meaning at all: it was poetry, sound, weird, refreshing language I was after. My particular reading here has depended on many other essays and creative pieces I was reading while encountering the novel for a second time: encountering it as a reader hoping, also, to write an essay—hoping to lock myself into a deeper kind of engagement with the work, hoping even, maybe, to ‘get something’). The Obituary absorbed these other texts, but it is not limited by them. It is forever a work that will have been. You must read it now. And forget everything this essay claims.

—Natalie Helberg

/

Selected Bibliography

Barthes, Roland. 1975. The Pleasure of the Text. New York: Hill & Wang. Print.

_____. “The Death of the Author.” Aspen (No. 5 + 6) (UbuWeb). Web. June 4. 2014.

Benhabib, Seyla. “Feminism and Postmodernism: An Uneasy Alliance.” Marxist Internet Archive. Web. July 1. 2014.

Bernstein, Charles. 1992. A Poetics. Cambridge; London: Harvard UP. Print.

Bersianik, Louky, et al. 2013. Theory, A Sunday. Brooklyn: Belladona. Print.

Butler, Judith. 2005. Giving an Account of Oneself. New York: Fordham UP. Print.

_____. 1997. The Psychic Life of Power. Stanford: Stanford UP. Print.

Dial M for Murder. Dir. Alfred Hitchcock. Warner Bros., 1954. Film.

Halpern, Rob. “Realism and Utopia: Sex, Writing, and Activism in New Narrative.” Journal of Narrative Theory 41.1 (2011): 82-124.

Poe, Edgar Allan. 2002. “Ligeia.” Edgar Allan Poe: Complete Tales and Poems. Edison: Castle Books. 569-79. Print.

Markotic, Nicole. “Narrotics: New Narrative and the Prose Poem.” Narrativity: A Critical Journal of Innovative Narrative (Issue One). Web. 10 July. 2014.

Moyes, Lianna, ed. 2002. Gail Scott: Essays on Her Work. Toronto; Buffalo; Chicago; Lancaster: Guernica. Print.

Place, Vanessa. 2005. Dies: A Sentence. Los Angeles: Les Figues. Print.

Scott, Gail. 2012. The Obituary. Callicoon: Nightboat. Print.

_____. 2002. “The Virgin Denotes:Or the Unreliability of Adverbs To Do with Time.” Narrativity: A Critical Journal of Innovative Narrative (Issue Three). Web. 10 July. 2014.

_____. 1999. My Paris. Toronto: Mercury. Print.

_____. 1993. Main Brides. Toronto: Coach House. Print.

_____. 1989. Spaces Like Stairs. Toronto: Women’s Press. 65-76. Print.

_____. 1987. Heroine. Toronto: Coach House. Print.

_____. 1981. Spare Parts. Toronto: Coach House. Print.

Stacey, Robert David, ed. 2010. Re: Reading The Postmodern: Canadian Literature and Criticism after Modernism. Ottawa: U of Ottawa P. Print.

Stephens, Nathalie. 2008. At Alberta. Toronto: Book Thug. Print.

/

Gail Scott is one of Canada’s most eminent experimental writers. Between 1967 and 1991, she worked as a journalist and eventually as an instructor of journalism in Montréal; during this time she also participated in Anglophone and Francophone feminist circles which deeply influenced her writing practice. She is the author of four novels, or ‘prose experiments’—Heroine (1987), Main Brides (1993), My Paris (1999), The Obituary (2010)—Spare Parts (1981), a collection of short stories, and Spaces Like Stairs (1989), a collection of essays. In 1979, she founded the French language cultural magazine Spirale; in the eighties, she co-founded and worked as an editor for the bilingual journal Tessera. More recently, alongside Mary Burger, Camille Roy and Robert Glück, she founded and edited the online journal Narrativity, whose express purpose was to supply a form of “missing nutrition” in articulating “ideas about theory-based narrative”; she co-edited the experimental narrative anthology Biting the Error (2004; shortlisted for a Lambda award in 2005) alongside the same writers.

Scott’s French to English translation of Michael Delisle’s Le Déasarroi du matelot was shortlisted for the Governor General’s award in translation in 2001. The Obituary was a finalist for the Montréal Book of the Year (Grand prix du livre de Montréal) in 2011. Her own work, the sentences which make it up, make much out of the bilingual and even multi-lingual language-contexts out of which they arise—they are clamorous, unique for their musicality. Scott has lived in a variety of places, including Paris, Grenoble, New York, and Stockholm, but her base continues to be Montréal.

—

Natalie Helberg completed an MFA in Creative Writing with the University of Guelph in 2013. She is currently studying philosophy at the University of Toronto. Some of her experimental work has appeared on InfluencySalon.ca and in Canadian Literature. She is working on a hybrid novel.

/\

/

Michael and Kate

Michael and Kate

William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth

Ralph Waldo Emerson

Ralph Waldo Emerson

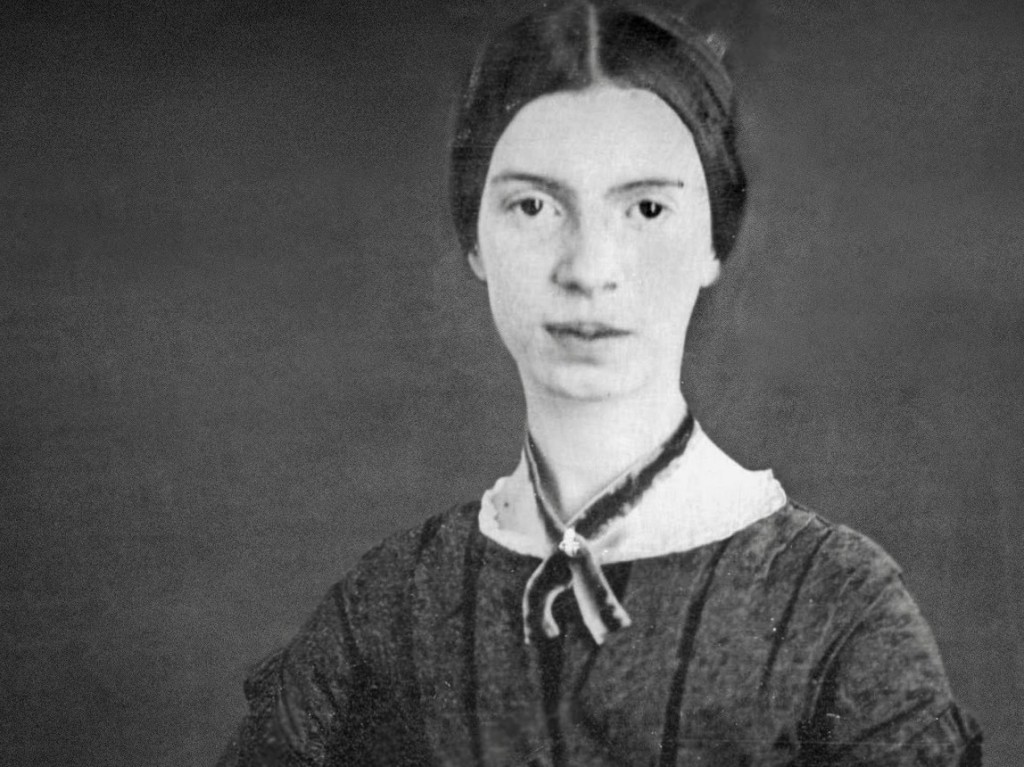

Samuel Bowles

Samuel Bowles

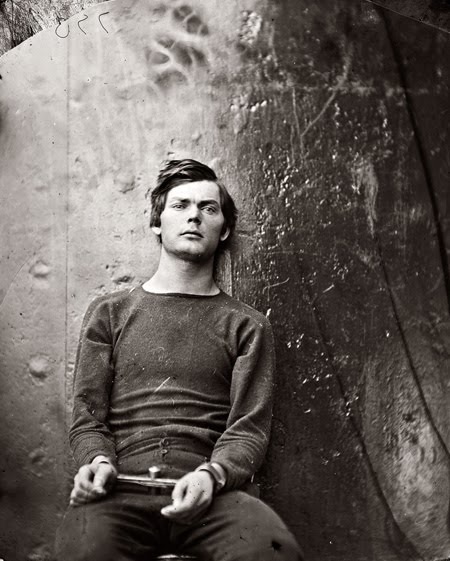

Still from the execution scene in The Passenger.

Still from the execution scene in The Passenger.

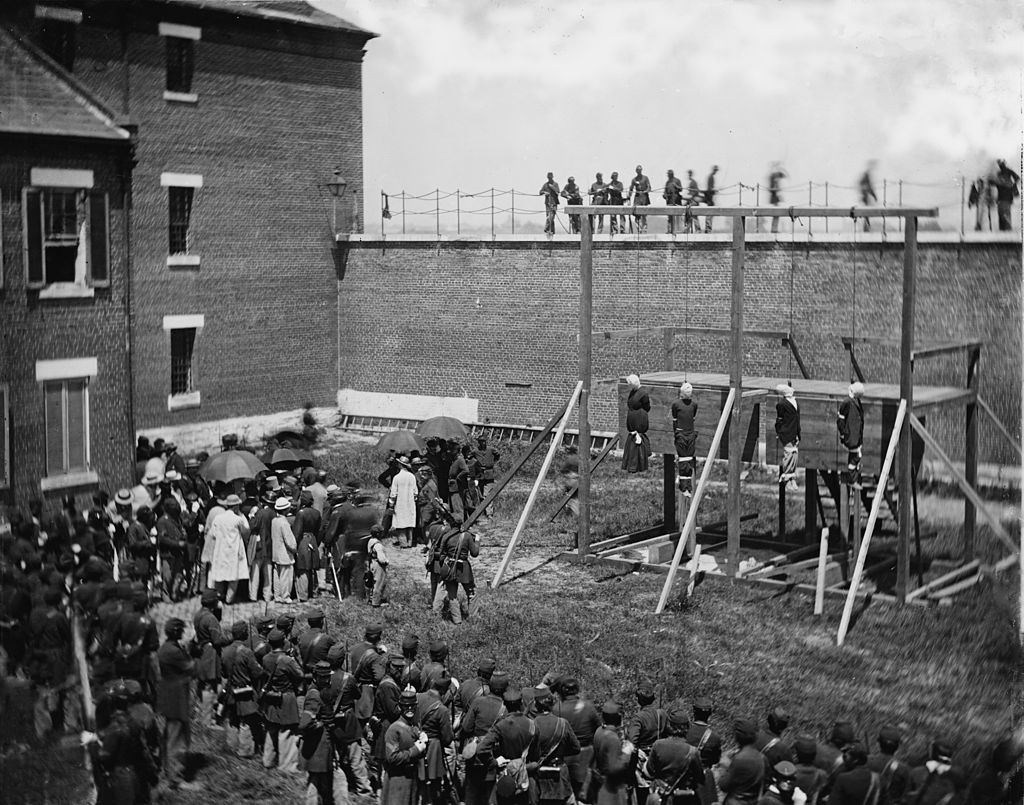

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865. Via Wikipedia.

Execution of Mary Surratt, Lewis Powell, David Herold, and George Atzerodt on July 7, 1865. Via Wikipedia.

Stills from a video no longer available at islammemo.cc.

Stills from a video no longer available at islammemo.cc.

Richard Farrell

Richard Farrell

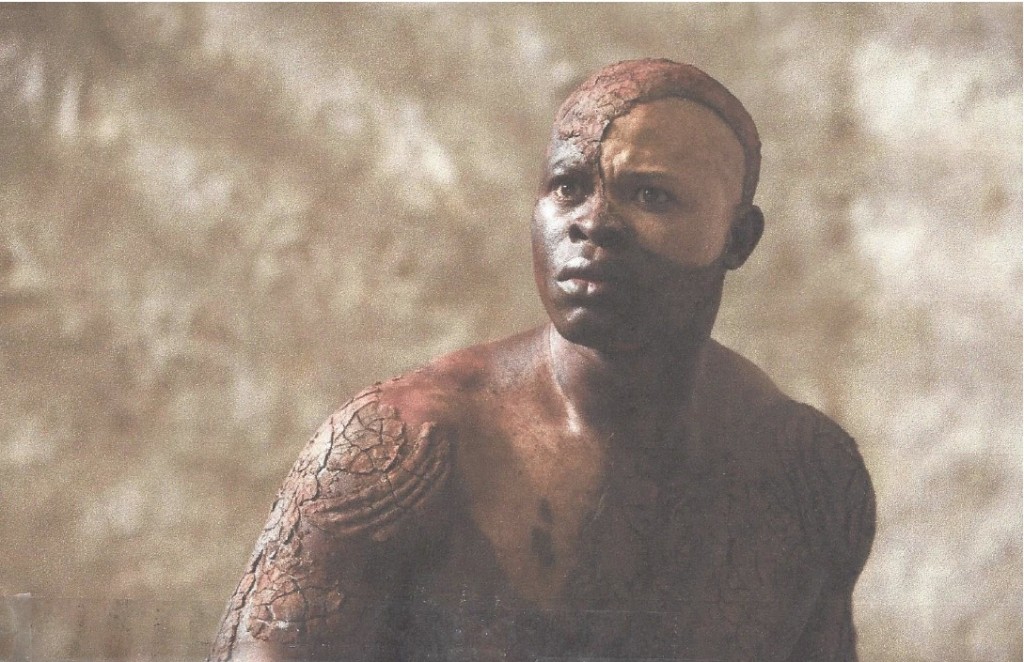

Djimon Hounsou as Caliban

Djimon Hounsou as Caliban